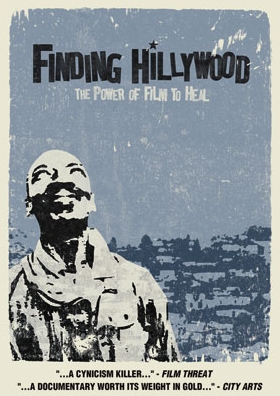

Who: Ni’coel Stark is the Development Producer for Finding Hillywood, which documents a group of aspiring Rwandan filmmakers producing their own films, and then screening them in remote villages throughout the country for thousands of viewers. Among the filmmakers are Ayuub Mago, a director and producer who coordinates The Hillywood Film Festival; Eric Kabera, a producer and founder of the Rwanda Cinema Center; Nicole Umutoni, a director and actress who is an executive assistant for the Rwanda Cinema Center; Richmond Runinara, a magazine editor and director; and Rodrigues Karekezi, a marketing assistant and actor. The documentary was conceived by filmmakers Leah Warshawski and Chris Towey during a trip to Rwanda in June of 2007, and they returned to film there three more times. CITS spoke with Stark in early 2011, as the project team was raising funds through Kickstarter to finance a rough cut of the film — then called Film Festival: Rwanda. Among those in the film industry who lent support to that effort was actor Harold Perrineau, who joined the producing team.

Who: Ni’coel Stark is the Development Producer for Finding Hillywood, which documents a group of aspiring Rwandan filmmakers producing their own films, and then screening them in remote villages throughout the country for thousands of viewers. Among the filmmakers are Ayuub Mago, a director and producer who coordinates The Hillywood Film Festival; Eric Kabera, a producer and founder of the Rwanda Cinema Center; Nicole Umutoni, a director and actress who is an executive assistant for the Rwanda Cinema Center; Richmond Runinara, a magazine editor and director; and Rodrigues Karekezi, a marketing assistant and actor. The documentary was conceived by filmmakers Leah Warshawski and Chris Towey during a trip to Rwanda in June of 2007, and they returned to film there three more times. CITS spoke with Stark in early 2011, as the project team was raising funds through Kickstarter to finance a rough cut of the film — then called Film Festival: Rwanda. Among those in the film industry who lent support to that effort was actor Harold Perrineau, who joined the producing team.

What types of subject matter are these Rwandan filmmakers exploring in their projects?

All of these films are in Kinyarwanda, and they’re about drug abuse, HIV-AIDS, divisionism between the Hutu and the Tutsis, domestic violence… and then they have some fun ones, like there’s animation where they’re just cute and funny and lighthearted. It spreads the gamut, but I think that there’s a lot of emphasis towards collectively dealing with the harder issues.

All of these films are in Kinyarwanda, and they’re about drug abuse, HIV-AIDS, divisionism between the Hutu and the Tutsis, domestic violence… and then they have some fun ones, like there’s animation where they’re just cute and funny and lighthearted. It spreads the gamut, but I think that there’s a lot of emphasis towards collectively dealing with the harder issues.

Richmond, his film is about the release of one of the murderers out of prison, and how he integrates again with feelings of guilt. Obviously, you can imagine the intensity of that. These filmmakers  are taking pretty big risks in their content, and there’s a lot of courage that exists.

are taking pretty big risks in their content, and there’s a lot of courage that exists.

Ayuub made a short film called Fora recently about his children (brothers) learning a moral lesson to take care of each other and not lie to their parents. He was also an actor in the film Kinyarwanda (that went to Sundance last year) and one of the writers for We Are All Rwandans, which also screened internationally. That was based on a true story of a particular school during the genocide.

Nicole, her films are centered around domestic violence. She works a lot with women’s issues. Her passion is about empowering women to do extraordinary things, and have more women involved in the film industry itself. She’s pretty eloquent in her passions about how a country can have all this business development, this technology development, all of this infrastructure as far as city and state and government — but if you don’t have human development, there’s a problem with that. And so, she’s committed to developing families and developing people individually as their country grows into more advanced and progressive ways of living. I think she sees that as of particular importance, that there needs to be equal amounts of human development.

and have more women involved in the film industry itself. She’s pretty eloquent in her passions about how a country can have all this business development, this technology development, all of this infrastructure as far as city and state and government — but if you don’t have human development, there’s a problem with that. And so, she’s committed to developing families and developing people individually as their country grows into more advanced and progressive ways of living. I think she sees that as of particular importance, that there needs to be equal amounts of human development.

Did Leah and Chris plan to specifically chronicle both Hutu and Tutsi Rwandan filmmakers?

They were captured by all of this imagery and the Rwanda Cinema Center, which is so unique and different. And they were really just looking for the people who were involved in this project, no matter who they were — whoever was most passionate about it, how they got there, why they’re interested, what their particular stories are outside of their particular histories. Most of the people who are at the Rwanda Cinema Center don’t necessarily have a direct relationship to the genocide, because it was 17 years ago and these are pretty young people still. None-the-less, Ayuub and the team seem to be working toward the healing of that Hutu and Tutsi divisionism. They don’t want there to be a divisionism anymore, so there’s not a lot of delineation between who’s Hutu and who’s Tutsi. We are flowing with what their vision is, and what their efforts are.

They were captured by all of this imagery and the Rwanda Cinema Center, which is so unique and different. And they were really just looking for the people who were involved in this project, no matter who they were — whoever was most passionate about it, how they got there, why they’re interested, what their particular stories are outside of their particular histories. Most of the people who are at the Rwanda Cinema Center don’t necessarily have a direct relationship to the genocide, because it was 17 years ago and these are pretty young people still. None-the-less, Ayuub and the team seem to be working toward the healing of that Hutu and Tutsi divisionism. They don’t want there to be a divisionism anymore, so there’s not a lot of delineation between who’s Hutu and who’s Tutsi. We are flowing with what their vision is, and what their efforts are.

Each one of the characters touch on their culture and their experience of how important it is because of the atrocities — how much more important it is to them, and how much more vivid their own personal experiences are as filmmakers. For instance, they speak to the fact how they’re watching the audiences look at their films, and to see the responses that are coming from their audiences because of the films they’re making. It validates the importance and the power of their work. Our film is an exploration of this hope, for sure, but in the context of something tragic.

Each one of the characters touch on their culture and their experience of how important it is because of the atrocities — how much more important it is to them, and how much more vivid their own personal experiences are as filmmakers. For instance, they speak to the fact how they’re watching the audiences look at their films, and to see the responses that are coming from their audiences because of the films they’re making. It validates the importance and the power of their work. Our film is an exploration of this hope, for sure, but in the context of something tragic.

What role do inflatable movie screens have in the Hillywood Film Festival?

Well, there are these inflatable screens that were donated by an American when Eric was first creating the film center. And so they had one originally, and since then they’ve had more donated, which is really helpful. And what happens is these screens get blown up, and they have the DVD player, and they have just their basic equipment, and they have to find electricity. So there is a little bit of comedy in their efforts in a country that’s not very technologically advanced, how they manage to deal with the technology that they have to have in order to project these films, and to create an event — how they manage to negotiate with the actual land and the lack of

Well, there are these inflatable screens that were donated by an American when Eric was first creating the film center. And so they had one originally, and since then they’ve had more donated, which is really helpful. And what happens is these screens get blown up, and they have the DVD player, and they have just their basic equipment, and they have to find electricity. So there is a little bit of comedy in their efforts in a country that’s not very technologically advanced, how they manage to deal with the technology that they have to have in order to project these films, and to create an event — how they manage to negotiate with the actual land and the lack of  technological infrastructure. They work really hard at it. And Rodrigues, one of our characters, he’s often “heroing” the festival because he’s finding electricity where there shouldn’t be any. It’s very creative problem solving when it comes to actually making this experience with the projector, and all of the components involved. It’s challenging and funny and frustrating all at the same time.

technological infrastructure. They work really hard at it. And Rodrigues, one of our characters, he’s often “heroing” the festival because he’s finding electricity where there shouldn’t be any. It’s very creative problem solving when it comes to actually making this experience with the projector, and all of the components involved. It’s challenging and funny and frustrating all at the same time.

What is the communal effect of watching these films outdoors, compared to a DVD at home?

I think that it’s really powerful. More powerful in that it’s a communal experience — that there’s thousands of people who are walking, standing and sitting to watch these films together. 1% of them have TVs, so DVD’s are not necessarily an option for this country. It’s much more feasible, and I think it actually works out in their best interest being forced to be much more communal in the experience. One of the reasons why we think it’s really powerful — not just for the obvious reason of all coming together, experiencing a film together — is that just as it is for us in America when we go and see a film, when the whole audience is present there is an energy. It’s this energy that creates a deeper effect when there’s human beings next to you in a filled theater. The more people, the more powerful I think it can be. So, when you’re in a country in this time period, 17 years after a genocide, to have still pretty deep wounds that maybe aren’t even in the consciousness of

I think that it’s really powerful. More powerful in that it’s a communal experience — that there’s thousands of people who are walking, standing and sitting to watch these films together. 1% of them have TVs, so DVD’s are not necessarily an option for this country. It’s much more feasible, and I think it actually works out in their best interest being forced to be much more communal in the experience. One of the reasons why we think it’s really powerful — not just for the obvious reason of all coming together, experiencing a film together — is that just as it is for us in America when we go and see a film, when the whole audience is present there is an energy. It’s this energy that creates a deeper effect when there’s human beings next to you in a filled theater. The more people, the more powerful I think it can be. So, when you’re in a country in this time period, 17 years after a genocide, to have still pretty deep wounds that maybe aren’t even in the consciousness of  particularly the children that still exists in the land — and absolutely exists in the experience of the people as a whole — you can’t heal it that quickly. But when they travel to the different locations, they pick particular locations that are very powerful. We have one that’s in Kibuye, and we filmed this where it’s an audience of 3,000 villagers, and they’re just standing there transfixed by these films, and the children are huddling together, and mothers have babies on their backs, and the teenagers are holding hands. And in the same location where they picked is a soccer stadium where 10,000 people were murdered during the genocide. But here they are now on that same blood-stained ground… people are standing again, but this time they’re bound by images of hope and reconciliation, rather than horror. So these I think also have, if not entirely conscious, a very subconscious power where it’s a kind of reclaiming the bad and making it

particularly the children that still exists in the land — and absolutely exists in the experience of the people as a whole — you can’t heal it that quickly. But when they travel to the different locations, they pick particular locations that are very powerful. We have one that’s in Kibuye, and we filmed this where it’s an audience of 3,000 villagers, and they’re just standing there transfixed by these films, and the children are huddling together, and mothers have babies on their backs, and the teenagers are holding hands. And in the same location where they picked is a soccer stadium where 10,000 people were murdered during the genocide. But here they are now on that same blood-stained ground… people are standing again, but this time they’re bound by images of hope and reconciliation, rather than horror. So these I think also have, if not entirely conscious, a very subconscious power where it’s a kind of reclaiming the bad and making it  into something good.

into something good.

Hillywood as a whole, and the team that’s involved in this festival, they have to continually build relationships with all of these areas around the country. Ayuub speaks to the fact that in the beginning there’s a lot of suspicion about “Who are these people?” “What are they gonna be filming?” There is an air of uncertainty and suspicion. And the more they build relationships with these communities around the country, the more trust there is, the more they experience smiles, the more they experience enthusiasm, rather than suspicion. And that is really meaningful to the team as well, because they can experience building relationships within their own country. And this platform provides a powerful way to do that. These communities that are all over the country, they can merge, and these relationships can continue to develop.

How have films shot in Rwanda by foreign directors been received by your Rwandan filmmakers?

They have had some international filmmakers who have been drawn to that area, because of the genocide. And there were some films that were created to help with education, and to help the learning in the schools, particularly for understanding the genocide. But a lot of those films that were brought to the country were created by no one in Rwanda, no one who had the direct experience. And I think a lot of the frustrations that we’ve heard from the Rwandan filmmakers is that there were the white protagonists that were seen as the heroes, and that isn’t so accurate. And so there was a bias that was created through those filmmakers.

They have had some international filmmakers who have been drawn to that area, because of the genocide. And there were some films that were created to help with education, and to help the learning in the schools, particularly for understanding the genocide. But a lot of those films that were brought to the country were created by no one in Rwanda, no one who had the direct experience. And I think a lot of the frustrations that we’ve heard from the Rwandan filmmakers is that there were the white protagonists that were seen as the heroes, and that isn’t so accurate. And so there was a bias that was created through those filmmakers.

The local language is Kinyarwanda. The films that they’ve been exposed to have to be translated from French or English. So, anything that’s not created in Rwanda by a Rwandan in Kinyarwanda, their experience is all translation. And actually, Richmond was hired as a translator to translate films in French or English into Kinyarwanda, and that’s where he discovered the power of film, and how even translation can be a creative interpretation. That you can interpret something really well and create a different effect of the film.

How do the Rwandan filmmakers in your documentary go about funding their films?

There is funding that happens. Eric Kabera travels around the world and tries to get more and more funding for the Rwanda Cinema Center, and the government helps a little bit. So there is a little bit of money, but not enough. All of the people who work at the Rwanda Cinema Center, they all have separate jobs outside of that to help pay their bills. And then they work at the cinema center to try to forward their own goals. So everybody’s working really hard, and there’s not enough money. And the main thing is to focus on providing work for them. A lot of donations come in the forms of equipment, which is great and they’re really grateful. But that doesn’t necessarily help them find work, and help them develop careers as filmmakers, so they actually can continue to do their work. And then the other side is that once they are able to complete a film, they don’t always know how to take that to the end. How do they market that film? How do they find any sort of distribution? It’s very, very limited. So we want to support them in finding work, and somehow instigate more work connections.

There is funding that happens. Eric Kabera travels around the world and tries to get more and more funding for the Rwanda Cinema Center, and the government helps a little bit. So there is a little bit of money, but not enough. All of the people who work at the Rwanda Cinema Center, they all have separate jobs outside of that to help pay their bills. And then they work at the cinema center to try to forward their own goals. So everybody’s working really hard, and there’s not enough money. And the main thing is to focus on providing work for them. A lot of donations come in the forms of equipment, which is great and they’re really grateful. But that doesn’t necessarily help them find work, and help them develop careers as filmmakers, so they actually can continue to do their work. And then the other side is that once they are able to complete a film, they don’t always know how to take that to the end. How do they market that film? How do they find any sort of distribution? It’s very, very limited. So we want to support them in finding work, and somehow instigate more work connections.

What have supporters like Harold Perrineau said appealed to them about this project?

What captures all of us is the same thing. I think that Harold and a lot of filmmakers in the industry have been so entranced by the themes of the film, because it’s the real reason all of us are so committed to filmmaking — it really is the power of story, and really for the common man. It’s to heal and to bring enjoyment and pleasure and all these reasons why all of us love film. It’s these very same reasons, it’s just that not everyone in the world has the opportunity to either enjoy or create or participate in that kind of storytelling. It’s a powerful theme. And then additionally the imagery, where you have thousands of people walking to see a film in their own language, made by their own people in a place where only 1% of the population even have TV’s. And most of them have never seen a film before, and certainly not in their own language. So, I would say that that is the reason it’s very compelling for all of us who are in the film industry at any level. That’s really it.

What captures all of us is the same thing. I think that Harold and a lot of filmmakers in the industry have been so entranced by the themes of the film, because it’s the real reason all of us are so committed to filmmaking — it really is the power of story, and really for the common man. It’s to heal and to bring enjoyment and pleasure and all these reasons why all of us love film. It’s these very same reasons, it’s just that not everyone in the world has the opportunity to either enjoy or create or participate in that kind of storytelling. It’s a powerful theme. And then additionally the imagery, where you have thousands of people walking to see a film in their own language, made by their own people in a place where only 1% of the population even have TV’s. And most of them have never seen a film before, and certainly not in their own language. So, I would say that that is the reason it’s very compelling for all of us who are in the film industry at any level. That’s really it.