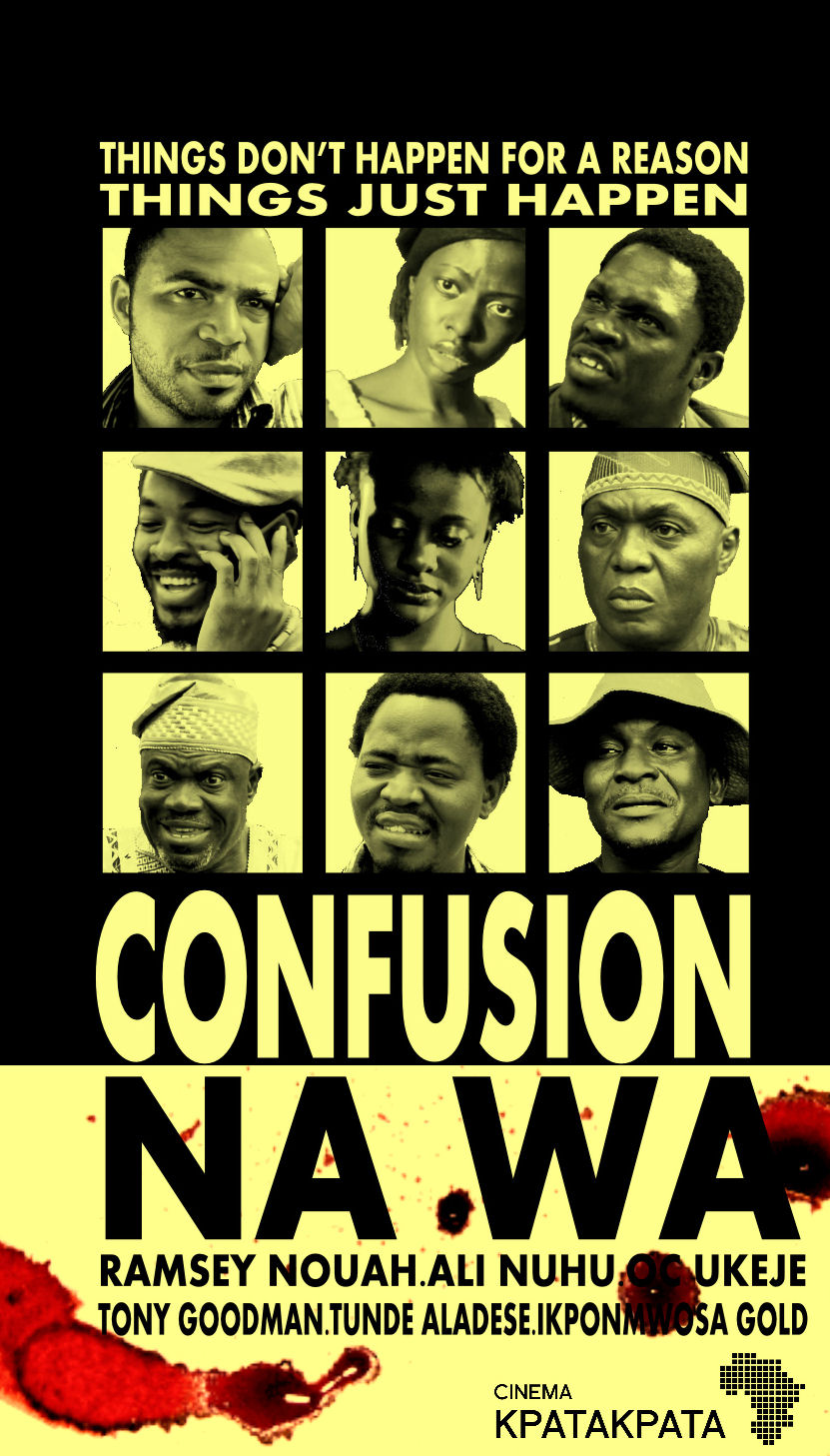

Who: Kenneth Gyang is a Nigerian filmmaker from the city of Jos, where he attended the National Film Institute. In 2012, he made his directorial debut with Blood and Henna, and followed it with 2013’s Confusion Na Wa — a title drawn from a line in a song by African musician Fela Kuti, and meaning “Confusion is Everywhere”. The film is a dark comedy, where a lost cell phone intertwines the fates of a group of strangers. But it also portrays larger societal concerns in modern Nigeria — including those of crime, corruption, tolerance, and a breakdown in the family structure. The film won “Best Picture” at the 2013 African Movie Academy Awards, and in May 2014 Gyang came to New York City to screen it on opening night of the 21st New York African Film Festival at Film Society of Lincoln Center. Camera In The Sun spoke with Gyang for a July 2014 interview about Confusion Na Wa, his approach to making the film profitable, and his thoughts on the future of Nigerian films.

Who: Kenneth Gyang is a Nigerian filmmaker from the city of Jos, where he attended the National Film Institute. In 2012, he made his directorial debut with Blood and Henna, and followed it with 2013’s Confusion Na Wa — a title drawn from a line in a song by African musician Fela Kuti, and meaning “Confusion is Everywhere”. The film is a dark comedy, where a lost cell phone intertwines the fates of a group of strangers. But it also portrays larger societal concerns in modern Nigeria — including those of crime, corruption, tolerance, and a breakdown in the family structure. The film won “Best Picture” at the 2013 African Movie Academy Awards, and in May 2014 Gyang came to New York City to screen it on opening night of the 21st New York African Film Festival at Film Society of Lincoln Center. Camera In The Sun spoke with Gyang for a July 2014 interview about Confusion Na Wa, his approach to making the film profitable, and his thoughts on the future of Nigerian films.

Where did you shoot Confusion Na Wa?

It was shot in Kaduna, but it was set in Jos. I grew up in Jos, and it is a really multicultural society. They have people from all over Nigeria, and all over West Africa coming to stay there. Back in the day, colonials from Britain were extracting mineral resources, so it was really huge. And so after all of that, it became a really multicultural city. But lately, in the 2000s, there’s been lots of religious crisis and riots. I’m a Christian. I grew up with Muslim friends. But right now, it’s very hard for these young kids to mingle — Christians with Muslims or Muslims with Christians — because of how it is. So what we decided to do is use Jos as a backdrop to set our film. Because if a small thing happens there — bam, people take up arms and start killing each other. That’s where we decided to set the film, because it’s all about how the decisions you make now can actually affect the next person without you knowing it. So I wanted to shoot it in Jos, and then of course there was a crisis when we were going to shoot. People were killing people, and so we had to move the production to a city that’s like 2 or 3 hours away. And then the day that my main actor was going to come from Lagos, there was another bomb explosion in Kaduna. So we basically shot under a curfew most of the time.

It was shot in Kaduna, but it was set in Jos. I grew up in Jos, and it is a really multicultural society. They have people from all over Nigeria, and all over West Africa coming to stay there. Back in the day, colonials from Britain were extracting mineral resources, so it was really huge. And so after all of that, it became a really multicultural city. But lately, in the 2000s, there’s been lots of religious crisis and riots. I’m a Christian. I grew up with Muslim friends. But right now, it’s very hard for these young kids to mingle — Christians with Muslims or Muslims with Christians — because of how it is. So what we decided to do is use Jos as a backdrop to set our film. Because if a small thing happens there — bam, people take up arms and start killing each other. That’s where we decided to set the film, because it’s all about how the decisions you make now can actually affect the next person without you knowing it. So I wanted to shoot it in Jos, and then of course there was a crisis when we were going to shoot. People were killing people, and so we had to move the production to a city that’s like 2 or 3 hours away. And then the day that my main actor was going to come from Lagos, there was another bomb explosion in Kaduna. So we basically shot under a curfew most of the time.

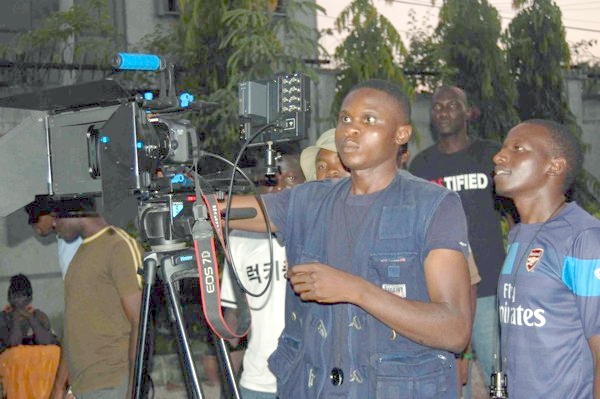

We shot it in 2010 for 14 days. We didn’t have a lot of money for post-production. My writer and co-producer is in the UK, and I’m in Nigeria. So obviously, when you edit, you have to think about how you are going to be in the same place? So we bought an iMac computer, and sent the movie back and forth. It took a long time in post-production because we were not in the same city at the same time. Not because we were doing anything creative in the edits. Because of budget, and to make sure the film comes out at the right time, we just had to take our time in the post-production.

We shot it in 2010 for 14 days. We didn’t have a lot of money for post-production. My writer and co-producer is in the UK, and I’m in Nigeria. So obviously, when you edit, you have to think about how you are going to be in the same place? So we bought an iMac computer, and sent the movie back and forth. It took a long time in post-production because we were not in the same city at the same time. Not because we were doing anything creative in the edits. Because of budget, and to make sure the film comes out at the right time, we just had to take our time in the post-production.

How did you go about releasing the film in Nigeria?

When the film was actually going to come out, there had been a huge outburst of theaters growing in Nigeria. People started going to theaters for something they called “New Nollywood” — or films that they show in theaters. But we have 10 screens to show films around Nigeria, servicing almost 200 million people. So it’s just for the prestige. You’re not going to actually make back your money from theaters. In Nigeria, DVD is really huge. So we said, “Yeah, of course we’re gonna do DVD. That’s where we’re gonna make back our money.” And of course VOD. All of these things: VOD and the theaters, they’re just going to add to the money you can make from DVD. Because DVD is your main market in Nigeria. And getting into theaters was definitely going to be hard. Because if you come in as an independent filmmaker, it’s really hard to negotiate with these people. Then we decided to enter film festivals. So winning “Best Picture” at the African Movie Academy Awards really helped us negotiate with them.

It’s cool that people can actually watch films on mobile phones. Because one of our deals we entered with another distributor is taking it to people via mobile phone. I don’t have a problem with people seeing it like that. But I will say, from what I’ve experienced, there wasn’t really much marketing in getting the films across via the phone. And I’m really glad that lots of other companies are not springing up in Nigeria. Because the cell phone industry is really a hit in Nigeria. So I’m sure that that will be a very good source of revenue for filmmakers

What role did your actors play in Confusion Na Wa‘s marketing?

When you’re marketing your film, you have to use the right actors. Even in casting, we had to get the right actors to do it. So of course, we had to go for actors who are box-office hits in Nigeria. And of course they have a pedigree. They’ve won a couple of awards before. Yes, those are not for this film. But all the actors have been rewarded in one way or another. We won “Best Picture” at the African Movie Academy Awards. Tunde Aladese was nominated for “Best Supporting Actress” at the [Nigerian Entertainment Awards], which she actually won. Ali Nuhu was nominated for “Best Actor” at the NEA. So at the end of the day, most of the actors in the film actually have one recognition or another. It’s not necessarily for this film. But I’m really glad that the actors decided to be a part of the film, because it started from the script. Now if you’re talking about awards for the script, I’ve always been confident about it. We were given funding by the Hubert Bals Fund in the Netherlands, and we were taken to be part of the Durban FilmMart in South Africa. So I knew that if we could just tell the story on screen as it is on paper, then lots of people would definitely like it. And that’s what we were able to do. So I wasn’t really surprised when we got these recognitions all over. It’s always been really well received.

What are your prospects for future film projects?

I formed a production company with my mates called KpataKpata, and it’s about making low-budget productions. Where I’m coming from, it’s all about low-budget productions. Because if you try to make a high-end film with a huge budget, how do you intend to make that money back? We have 10 theaters in Nigeria. And if you are going to release your film on DVD, there’s lots of piracy. How would you break even? I don’t want to be a filmmaker that is all about, “Oh yeah man, you made a high-budget film.” I want to be a filmmaker that made a low-budget film that made a lot of money. That’s how you gain respect. That’s how Steven Spielberg got respect in the United States. For me, that is what is really important. It’s not about the budget. Our films are getting respected, but I always say, “You have to think about distribution and marketing, before you put a huge budget in your film.” Would I come to you to tell you, “OK, give me one million dollars to make a film”? No, I will never do that. I’ll work out all the modalities, and all the stuff that needs to get into marketing and distributing a film. Then, knowing that, I’m actually going to make back that money. So that’s what we stand for: low-budget productions. And that’s why I’ll never take myself away from Nollywood. Because that’s what Nollywood has been able to show me back home. It’s all about making low-budget productions and making money out of it. Those marketers, they make low-budget productions, and they make money out of it. That for me is what film is. Film is a business. It’s not all about making the film. I mean, I could take five million dollars and make a film, and then make $500,000. But at the end of the day, who’s gonna give you money again to make another film? It’s business, and I need to pay my bills.

I formed a production company with my mates called KpataKpata, and it’s about making low-budget productions. Where I’m coming from, it’s all about low-budget productions. Because if you try to make a high-end film with a huge budget, how do you intend to make that money back? We have 10 theaters in Nigeria. And if you are going to release your film on DVD, there’s lots of piracy. How would you break even? I don’t want to be a filmmaker that is all about, “Oh yeah man, you made a high-budget film.” I want to be a filmmaker that made a low-budget film that made a lot of money. That’s how you gain respect. That’s how Steven Spielberg got respect in the United States. For me, that is what is really important. It’s not about the budget. Our films are getting respected, but I always say, “You have to think about distribution and marketing, before you put a huge budget in your film.” Would I come to you to tell you, “OK, give me one million dollars to make a film”? No, I will never do that. I’ll work out all the modalities, and all the stuff that needs to get into marketing and distributing a film. Then, knowing that, I’m actually going to make back that money. So that’s what we stand for: low-budget productions. And that’s why I’ll never take myself away from Nollywood. Because that’s what Nollywood has been able to show me back home. It’s all about making low-budget productions and making money out of it. Those marketers, they make low-budget productions, and they make money out of it. That for me is what film is. Film is a business. It’s not all about making the film. I mean, I could take five million dollars and make a film, and then make $500,000. But at the end of the day, who’s gonna give you money again to make another film? It’s business, and I need to pay my bills.

Did exposure to Indian “Bollywood” films affect your taste in films?

In the north, we’re exposed to a lot of Indian films. There’s an industry in the north called “Kannywood”. It is based in Kano, which is the biggest city in northern Nigeria. They do films in Hausa, and Hausa is one of the biggest languages in Africa. It’s just before or after Swahili. So people who do films in Kannywood make them after the Bollywood medium — musicals where there has to always be people singing and dancing. It’s melodramatic. You’re talking about this person who is in love with this girl, and stuff happens just like in Bollywood films.

But the thing is, I’m not so sure if [film taste] is about the films that you are exposed to. I think it has to do with interest. Because I met people from the Southern part of Nigeria who were also into the sort of films that I watch. And when you’re having conversations, you actually have interesting conversations. It’s the same thing with northerners. There are some people who actually watch the kind of films that I watch, or who are interested in subject matter, or trying to tell the story in a particular way. So it has absolutely nothing to do with the sort of films that you are exposed to.

How did you get into filmmaking?

The National Film Institute is in Jos, and I’m from Jos. So that’s the film school I went to, but it was actually purely by accident. Because I was supposed to go to a conventional university to study mass communication. And I’m from Jos, but I didn’t know then that there was a film school there. So I was just passing by a radio station in Jos, and I saw a poster advertising the National Film Institute. And that same day, I just went to the school to ask about what it takes to enter. So I did a course in cinematography, and then I later did a degree in producing and directing.

The training in the film school is cool, but I think it’s all about how you actually want to tell stories. In Nigeria, we have the conventional Nollywood films that a lot of people are aware of around the world. But when I was in film school, I was always thinking, “How can you tell your stories differently?” So I was really interested in world cinema, and films done by Alejandro González Iñárritu, Fernando Meirelles, and of course Quentin Tarantino — how he tells his stories, his dialogue, his characters. And I started thinking, “How can we make something different.” So I attended the Berlinale Talents, because my film was selected in official competition. I went there and interacted with the people. So I had lots of education outside the classroom, by watching a lot of films and by interacting with other people. When you see some of these low-quality films coming out of Nigeria, you always wonder, “Is it because we can’t actually do it? What is the problem?”

When I was at the National Film Institute, we’d always go through a series of exercises. And some of the best students would go to attend a workshop in Burkina Faso at Imagine, run by Gaston Kaboré — who is a prominent African filmmaker. So going to Imagine actually opened a lot to me when it comes to storytelling. Because I had a lot of tutors analyzing a story, breaking down a film and all of that. We’d discuss the European model of filmmaking, the American model of filmmaking. So that actually opened my eyes. I didn’t get that in the film school, to be honest. That’s what Burkina Faso did for me. At the end of the day, I can actually decipher a film by just watching it, based on what I learned in Burkina Faso.