Who: Marisa Scheinfeld is a photographer based in Westchester County, New York. Raised in the Catskill Mountains of nearby Sullivan County, Scheinfeld grew up in the 1980s and 90s amidst the last throes of the “Borscht Belt” era of local hotels aimed at a Jewish clientele. Many of those hotels boasted entertainment venues that together formed an upstate entertainment circuit worked by generations of musicians and comedians, who then often used its notoriety as a springboard to larger tours, as well as cinema and television careers. In recent years, Scheinfeld returned to many of those now-closed hotel properties, and began photographing their physical remains. Her resulting work portrays hotel buildings in varying states of decay, or gone altogether. In August 2014, she signed a publishing deal with Cornell University Press to turn those photos into a book. That same month, I interviewed Scheinfeld at Yeshiva University Museum as part of a report for The Jewish Channel, in advance of the September 10th opening of a Y.U.M. exhibition of her work titled “Echoes of the Borscht Belt”.

Who: Marisa Scheinfeld is a photographer based in Westchester County, New York. Raised in the Catskill Mountains of nearby Sullivan County, Scheinfeld grew up in the 1980s and 90s amidst the last throes of the “Borscht Belt” era of local hotels aimed at a Jewish clientele. Many of those hotels boasted entertainment venues that together formed an upstate entertainment circuit worked by generations of musicians and comedians, who then often used its notoriety as a springboard to larger tours, as well as cinema and television careers. In recent years, Scheinfeld returned to many of those now-closed hotel properties, and began photographing their physical remains. Her resulting work portrays hotel buildings in varying states of decay, or gone altogether. In August 2014, she signed a publishing deal with Cornell University Press to turn those photos into a book. That same month, I interviewed Scheinfeld at Yeshiva University Museum as part of a report for The Jewish Channel, in advance of the September 10th opening of a Y.U.M. exhibition of her work titled “Echoes of the Borscht Belt”.

What inspired you to begin photographing Borscht Belt hotels?

I was living in California going to graduate school, and I got the advice to shoot what I know. I knew my hometown had this vibrant history, which had largely passed. I had seen the hotel era decline in the later-’80s, growing up there as a kid, and I wanted to call attention to it. Ultimately, I created a narrative about the Borscht Belt as it looks today. Borscht Belt hotels predominately closed in the ’80s and ’90s. However, there are a selection of hotels, such as the Neville, that only closed a few years ago. Each hotel is in a different state of ruin, whether it was lying for 5, 10, 20 years or 30 years. So each hotel presented a new landscape. Within that landscape, there was the history of the Borscht Belt — predominantly a Jewish-American vacation resort started because of antisemitism in the 1920s, when Jews were banned from most hotels. Then the industry grew and boomed in the ’50s and ’60s. By the ’70s and ’80s, it died out for a number of reasons. I don’t think it’s fair to say that there was one major reason for the decline. Throughout the ’80s and ’90s, it was evident that the industry, and the area’s economy, had taken a downturn. Since then, there’s been a lot of hope for the area to experience a rebirth — which I do hope it does, and feel that it has a lot of potential.

I was living in California going to graduate school, and I got the advice to shoot what I know. I knew my hometown had this vibrant history, which had largely passed. I had seen the hotel era decline in the later-’80s, growing up there as a kid, and I wanted to call attention to it. Ultimately, I created a narrative about the Borscht Belt as it looks today. Borscht Belt hotels predominately closed in the ’80s and ’90s. However, there are a selection of hotels, such as the Neville, that only closed a few years ago. Each hotel is in a different state of ruin, whether it was lying for 5, 10, 20 years or 30 years. So each hotel presented a new landscape. Within that landscape, there was the history of the Borscht Belt — predominantly a Jewish-American vacation resort started because of antisemitism in the 1920s, when Jews were banned from most hotels. Then the industry grew and boomed in the ’50s and ’60s. By the ’70s and ’80s, it died out for a number of reasons. I don’t think it’s fair to say that there was one major reason for the decline. Throughout the ’80s and ’90s, it was evident that the industry, and the area’s economy, had taken a downturn. Since then, there’s been a lot of hope for the area to experience a rebirth — which I do hope it does, and feel that it has a lot of potential.

I believe it’s The New York Times that said in 1953 there were 538 hotels in the Borscht Belt, of various sizes, ranging from small hotels to resorts. And that doesn’t [include] the thousands of bungalow colonies that existed. The area was year-around known for leisure, entertainment, and also was coined as the birthplace of standup comedy.

Grossinger’s is one of the more famous ones. When I moved up to the area with my family in 1986, we lived sandwiched in between the Concord and Kutsher’s. Those hotels primarily were the ones I went to as a kid. And I worked at the Concord as a lifeguard when I was 16. Grossinger’s was previously unknown to me, in the sense that I had never visited it. As a result, I’ve only gone to it while working on this project. The hotel was internationally known. It had its own post office, its own landing strip for planes.

What is the general condition of the hotels you photograph?

I’ve been photographing the hotels that have been abandoned. Many hotels have been re-purposed. But my project only focuses on the ones that were, if you will, left over. Each was very much like a ruin where you see the elements of nature which have inevitably reclaimed the sites. Lots of foliage is coming through. Colors of greens are revealed in the summer, leaves are crackling in the fall, and then moving on to the winter where everything freezes. I was always amazed by the colors and the textures that I would see. That’s a big part of the project, besides being about this historic site.

I would also find hotels that were decomposing, where many of them were unsafe. I always made sure to go with a friend — someone who would come with me in case something would happen. I wouldn’t want to fall through a floor. They are very unstable places. So I started to learn the geography and the landscape of each hotel. Because I went back and visited each many times to capture it in different seasons. Also, what was interesting to me was evidence of humans who had come in and decorated the hotels with paintballs or graffiti. Even remnants of humans who had been living there or been hanging out there.

There were certain hotels, such as the Heiden hotel, which had burned down. That hotel was interesting, because I found its pool on Google Maps, while the tennis courts are the only part of the hotel visible from the road. Certain hotels were easier to find, like Grossinger’s, which is still standing in its many different buildings. Other hotels were harder to find. You might see a marking, such as two pillars on a side of a road that would indicate something was once there. And if you got out of the car, and walked a few yards, you might see a foundation. Typically, one would come across a pool, because those were the things that lasted if the hotel burned down — which in many cases they did, or were leveled and demolished.

How did Echoes of the Borscht Belt end up at Y.U. Museum?

When I moved back to New York, I had been trying to find a venue for this work. Somewhere where it was appropriate, and where it fit. I met with the director and the curators of Yeshiva University Museum, and they were interested to host an exhibition. So I’m very proud that it’s here, and happy the way that it turned out.

When I moved back to New York, I had been trying to find a venue for this work. Somewhere where it was appropriate, and where it fit. I met with the director and the curators of Yeshiva University Museum, and they were interested to host an exhibition. So I’m very proud that it’s here, and happy the way that it turned out.

The archival photographs on loan for the exhibition come from YIVO. I knew the folks at YIVO from a prior job that I had, so I had a connection. YIVO let me access a Grossinger’s archive, comprised of amazing black & white photographs depicting Grossinger’s at a certain period of time. You’ll see in the exhibition people like Sammy Davis Jr. and Duke Ellington. That is just a glimpse at the number of people, both known and average folk, who came up to Grossinger’s and made great memories and had wonderful times.

On her picture of the indoor pool at Grossinger’s

This chair is one of the many objects that I found that I thought was interesting. [It] was a magnificent room, and still is architecturally unbelievable. And here you have this lone chair that’s sitting in this pool that has been abandoned, where you see on the floor a carpet that has turned to moss. So this is a very powerful picture, where you see nature has reclaimed. And the chair almost acts like the human body. Even though the sites are absent of people, they’re very much alive in a different way.

Walking through these ruins can be astonishing. It could also be disturbing. The smells are often of foliage, of greenery. They are also smells of paint and mold. The senses are very attuned to colors, and things in the way — particularly beautiful things, such as this floor growing through amid this abandoned and almost-decaying space.

On her picture of the Commodore Hotel in Swan Lake

This was one of the only structures remaining of the former hotel, besides the pool. I believe it was once the showroom that hosted many shows, comedy acts, musicians, and entertainers. Today, it’s been turned into a skate park. You can see how there are actually ramps, and that local kids have made these hotels places for their own forms of recreation. So in many ways, the hotels have been re-purposed, devoid of their original intention, but undoubtedly used.

I never ran into people. Sometimes I wished I would have ran into a group of kids, or adults who might have been spray-painting or skateboarding. I think it could have provided a very interesting contemporary image. Sometimes I ran into evidence of people that might have been squatting or living at the hotels. But ultimately, I never felt unsafe.

On her picture of the coffee shop at Grossinger’s

The coffee shop at Grossinger’s really hits the nail on the head, if you will, of this empire known as the Borscht Belt that had declined. So you have these beautiful green stools that have withstood time, and seasons, and change, and destruction behind it. And the absence of the counter really depicts this era having collapsed.

Looting is definitely, and has been, a problem with many of the hotels — Grossinger’s being one of them, the Pines being another — where the hotels were ultimately left. While the hotels might be owned by someone else other than the original owners, many have gone in them to loot for copper wiring or anything of value.

What’s your take on the future of Sullivan county’s Borscht Belt region?

I believe the county has been hoping, as many have been, that the area experiences a rebirth. If you look at the history of Sullivan County, the Borscht Belt was its third industry. So there were two before that, and the area has always picked itself back up again. So whether its something like casinos, or health resorts, or a spa that comes to the area, I think there’s a lot of red tape to get through. But my hope is that the project calls attention to the region again, its potential, and that we might see a rebirth.

I believe the county has been hoping, as many have been, that the area experiences a rebirth. If you look at the history of Sullivan County, the Borscht Belt was its third industry. So there were two before that, and the area has always picked itself back up again. So whether its something like casinos, or health resorts, or a spa that comes to the area, I think there’s a lot of red tape to get through. But my hope is that the project calls attention to the region again, its potential, and that we might see a rebirth.

There’s definitely a visible Jewish life with the locals that live up there. There’s a large Jewish population, but the area has a wide variety of ethnic backgrounds. Growing up there, I went to temple, and I had a Jewish life. And today, there’s a large Orthodox population that inhabits the area in the summer, who have bought many of the bungalow colonies, and even some of the hotels. So there is a vibrant Jewish life up there. Predominantly in the summer, but throughout the winter as well.

There are definitely still a lot of people who still go up to Sullivan county. There are pockets of the county, such as Rock Hill where I’m from, that have a beautiful boutique hotel, a juice bar, a coffee shop. There are places like Narrowsburg and Callicoon that have seen a true revitalization, where New Yorkers are buying homes up there, going to bed & breakfasts on the weekend. So while my project makes it seem like nothing is going on, there is a beautiful life to be lived and enjoyed in Sullivan County, and much to go for if you vacation. The area is very close to New York. I think that’s the reason why it boomed, and the reason why it can boom again.

Do you have mementos from the hotels you photograph?

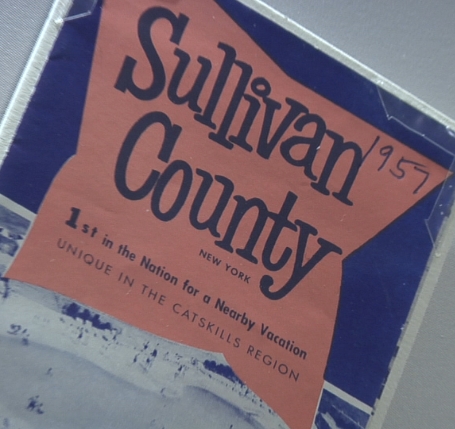

When I started the project, I did a lot of research. I looked at a lot of images. I read a lot of books. The Borscht Belt has been widely documented in memoirs, archival works, across the board. And while photographing, concurrently I was looking for objects and ephemera. Because the era produced anything from postcards to picture viewers, which are exhibited in the exhibition. There are brochures, menus, and I’ve largely been collecting a lot of it off of eBay. Some have been given to me. Some I have found at the hotel sites.

I think inherently by nature the photographer is a collector. Whether of moments, or memories. So this ephemera collection is largely mine. Some of it has been borrowed by the center’s partners — specifically YIVO.

Here we have a t-shirt of Kutsher’s which is part of my ephemera collection. And Kutsher’s holds a very dear place in my heart. It was one of the hotels that I used to go to as a kid with my grandparents. So when I came across a t-shirt, I bought it.

Growing up in the Borscht Belt region, it was unavoidable to hear a story about the boom times of the area. Whether you were driving in the car, or someone recalled a story over the dinner table about a show that they saw, or something they did, or a memorable life event. For me, growing up in the ’80s, I went to many of these hotels. It didn’t dawn on me that they were less populated. I did not understand how busy they actually were. But for me, they were very much places where I went, and did what people used to do. Whether I went to the pool, or I played bingo.

My grandparents met while my grandmother was hitchhiking through the county’s winding roads. So our family story begins there. My father used to go up to the county with my aunt in the summers. They went to a bungalow colony. So it was unavoidable that we would drive on a road, and my dad would point out, “We used to go there!” or “Your grandmother used to have a bungalow there.” And everyone lights up when they talk about the area. It was a place where people had their best memories. And it has brought people together while I have been doing this project. Whether someone’s been reaching out to me to tell me their story, or I meet someone who tells me about a hotel that I didn’t know that existed. So the Borscht Belt brought people together, and the project that I’ve been working on in a very nice way is still bringing people together.

My grandparents met while my grandmother was hitchhiking through the county’s winding roads. So our family story begins there. My father used to go up to the county with my aunt in the summers. They went to a bungalow colony. So it was unavoidable that we would drive on a road, and my dad would point out, “We used to go there!” or “Your grandmother used to have a bungalow there.” And everyone lights up when they talk about the area. It was a place where people had their best memories. And it has brought people together while I have been doing this project. Whether someone’s been reaching out to me to tell me their story, or I meet someone who tells me about a hotel that I didn’t know that existed. So the Borscht Belt brought people together, and the project that I’ve been working on in a very nice way is still bringing people together.