Who: James Payne is an Oklahoma-based filmmaker and producer, whose documentary work has often looked at his home state. His subjects include catfish noodlers, an environmentally-devastated mining town, and the state’s oldest maximum-security prison. While traveling in Japan with an American Bluegrass band in 2007, Payne met local musician Masuo Sasabe, who introduced him to other Japanese musicians with a love for American Country music. Payne was taken to Tokyo honky-tonk bar, Rockytop, in the city’s Ginza District, where he got a first-hand view of a Japanese Country music subculture that goes back nearly 70 years to the end of World War II. Intrigued, Payne decided to make it the subject of his next documentary, and returned to Japan to film musicians and honky-tonks around Tokyo-Yokohama. Payne returned again to interview musician Charlie Nagatani, and shoot the International Country Gold Festival in Kumamoto, which Nagatani founded. The resulting film is titled Far Western, and Camera In The Sun interviewed Payne about it for a September 2014 interview in the midst of a $35,000 Kickstarter campaign to fund a final trip to Japan to wrap up musician narratives in Tokyo and Kanazawa — as well as film both this year’s ICGF, and the Tajimi Mountain Time Bluegrass Festival.

Who: James Payne is an Oklahoma-based filmmaker and producer, whose documentary work has often looked at his home state. His subjects include catfish noodlers, an environmentally-devastated mining town, and the state’s oldest maximum-security prison. While traveling in Japan with an American Bluegrass band in 2007, Payne met local musician Masuo Sasabe, who introduced him to other Japanese musicians with a love for American Country music. Payne was taken to Tokyo honky-tonk bar, Rockytop, in the city’s Ginza District, where he got a first-hand view of a Japanese Country music subculture that goes back nearly 70 years to the end of World War II. Intrigued, Payne decided to make it the subject of his next documentary, and returned to Japan to film musicians and honky-tonks around Tokyo-Yokohama. Payne returned again to interview musician Charlie Nagatani, and shoot the International Country Gold Festival in Kumamoto, which Nagatani founded. The resulting film is titled Far Western, and Camera In The Sun interviewed Payne about it for a September 2014 interview in the midst of a $35,000 Kickstarter campaign to fund a final trip to Japan to wrap up musician narratives in Tokyo and Kanazawa — as well as film both this year’s ICGF, and the Tajimi Mountain Time Bluegrass Festival.

What inspired you to begin filming Far Western?

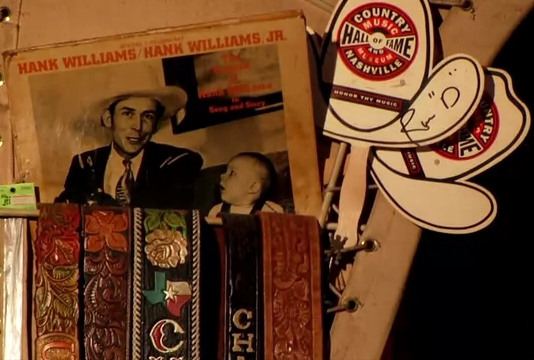

I was producing a live performance tour for an Americana band that was 10-city tour of Asia, five cities in Japan, through the U.S. embassy. And I grew up in the Midwest with a range of music forms: Western, Swing, Hillbilly, Country & Western, Bluegrass. So we met these players, and they started taking us to these tiny little bars in Tokyo, like the Rockytop, and the Nashville, and the Lonestar. You could tell by the walls, with all the memorabilia and visiting American artists, that they had been obsessed with the music for decades. It was just a really conspicuous transplant of my own culture to the center of Tokyo.

I was producing a live performance tour for an Americana band that was 10-city tour of Asia, five cities in Japan, through the U.S. embassy. And I grew up in the Midwest with a range of music forms: Western, Swing, Hillbilly, Country & Western, Bluegrass. So we met these players, and they started taking us to these tiny little bars in Tokyo, like the Rockytop, and the Nashville, and the Lonestar. You could tell by the walls, with all the memorabilia and visiting American artists, that they had been obsessed with the music for decades. It was just a really conspicuous transplant of my own culture to the center of Tokyo.

What impact did World War II have on the creation of this subculture?

The war is important, because I think the people were in such a state of distress. Then the U.S. government, for whatever reason, establishes this radio network, and they would later go on to oversee their television network — which would be equally as influential for motion pictures. But when I look at the Japanese folk music forms, they’re very different. I mean, they’re not an 8-note scale, so they have more of these meandering melodies. And they’re not as simply rhythmic as this early Country. You know, a lot of that is almost pre-Country music, if we’re talking about the Carter Family or Jimmie Rodgers, and these things that would later become Country. So I think that must have sounded very very different, and kind of exciting. There’s a musicologist from Columbia named Aaron Fox, and he did a study about the ability for this music to be transplanted to the Australian Outback, where Dolly Parton is selling out stadiums, and Don Williams is selling out soccer arenas in West Africa. He talks about there being this simplicity and sentimentality to the melody lines. And he talks about the steel guitar being the weeping guitar, simulating human crying, and there being these emotional common denominators that somehow strike a chord in all of these disparate places.

The war is important, because I think the people were in such a state of distress. Then the U.S. government, for whatever reason, establishes this radio network, and they would later go on to oversee their television network — which would be equally as influential for motion pictures. But when I look at the Japanese folk music forms, they’re very different. I mean, they’re not an 8-note scale, so they have more of these meandering melodies. And they’re not as simply rhythmic as this early Country. You know, a lot of that is almost pre-Country music, if we’re talking about the Carter Family or Jimmie Rodgers, and these things that would later become Country. So I think that must have sounded very very different, and kind of exciting. There’s a musicologist from Columbia named Aaron Fox, and he did a study about the ability for this music to be transplanted to the Australian Outback, where Dolly Parton is selling out stadiums, and Don Williams is selling out soccer arenas in West Africa. He talks about there being this simplicity and sentimentality to the melody lines. And he talks about the steel guitar being the weeping guitar, simulating human crying, and there being these emotional common denominators that somehow strike a chord in all of these disparate places.

On International Country Gold Festival founder Charlie Nagatani:

Charlie was not yet a teenager during World War II, and didn’t go to war, but grew up near a base. Like a lot of guys of his generation, he got exposed to music through the Far East Network. I think it was an opportunity to make a living. He played the “Freedom Ports”, as they were called — which would have been the Philippines, South Korea, Thailand — and played the bases. He was a professional touring musician at a time where there was very little opportunity for Japanese musicians to do that. He comes back in the ’70s, opens up a “live house”, which is what they call a little honky-tonk, in Kumamoto. It’s crazy. The guy literally plays like 340 shows a year. He has a house band, and he puts on this festival. At some point, he becomes recognized for having the largest event in Japan for Country music. And he has this mantra, which is “global peace through country music”. He gets invited to Clinton’s White House, and now he’s on a 20-year stretch of Grand Ole Opry performances. So for me, he has this wonderful drive and obsession, which is captivating as a documentary subject.

Charlie was not yet a teenager during World War II, and didn’t go to war, but grew up near a base. Like a lot of guys of his generation, he got exposed to music through the Far East Network. I think it was an opportunity to make a living. He played the “Freedom Ports”, as they were called — which would have been the Philippines, South Korea, Thailand — and played the bases. He was a professional touring musician at a time where there was very little opportunity for Japanese musicians to do that. He comes back in the ’70s, opens up a “live house”, which is what they call a little honky-tonk, in Kumamoto. It’s crazy. The guy literally plays like 340 shows a year. He has a house band, and he puts on this festival. At some point, he becomes recognized for having the largest event in Japan for Country music. And he has this mantra, which is “global peace through country music”. He gets invited to Clinton’s White House, and now he’s on a 20-year stretch of Grand Ole Opry performances. So for me, he has this wonderful drive and obsession, which is captivating as a documentary subject.

He plays mostly covers, and he has his anthem — written in English. He only speaks to me in English, and his English is pretty good. But he kind of refuses to speak in Japanese. There are some players that have transformed the music, and are singing in Japanese. But he is not one of them.

On the Ozaki Brothers:

The Ozakis are close to Charlie’s age, maybe a little bit older. I think they grew up in a wealthier family. Their father was a businessman prior to the war, and he traveled. So they had some exposure to Western music: Jazz, South American music, some prewar Big Band pop stuff, and some traditional music like “You Are My Sunshine“. So they loved the music when they were kids. They tell this story about listening to these records during the war that were like a .78, but floppy, that their father had brought back from America. Possession of Western media was considered contraband, and punishable. So they listened to all these songs in their basement, and learned them. Then they go to university, and they’re obsessed with music, and they find these clubs. They end up forming what we believe is the first Japanese Bluegrass band, called The East Mountain Boys. So they’re just fundamental in establishing that music form.

The Ozakis are close to Charlie’s age, maybe a little bit older. I think they grew up in a wealthier family. Their father was a businessman prior to the war, and he traveled. So they had some exposure to Western music: Jazz, South American music, some prewar Big Band pop stuff, and some traditional music like “You Are My Sunshine“. So they loved the music when they were kids. They tell this story about listening to these records during the war that were like a .78, but floppy, that their father had brought back from America. Possession of Western media was considered contraband, and punishable. So they listened to all these songs in their basement, and learned them. Then they go to university, and they’re obsessed with music, and they find these clubs. They end up forming what we believe is the first Japanese Bluegrass band, called The East Mountain Boys. So they’re just fundamental in establishing that music form.

On musicians Juta Sagai and Masuo Sasabe:

Juta is baby boomer age. His parents would have been adults during the war. Same with Masuo Sasabe. A lot of those guys were going to college in the late-’60s, early-’70s, and would have been influenced by the Folk revival: everything that happened in the early-’60s, through the ’60s in America with Woody Guthrie, and Pete Seeger, and The Kingston Trio, and The Mamas & the Papas. All that stuff then started flowing into rock and roll, and they were all heavily influenced by it too. Of course, part of that revival in the States was going back and looking at the roots of those folk traditions. Woody Guthrie becomes incredibly important again at that time, near his death [in 1967], with all that stuff that he wrote during the [Works Progress Administration]. The same thing was happening in parallel in Japan.

Juta is baby boomer age. His parents would have been adults during the war. Same with Masuo Sasabe. A lot of those guys were going to college in the late-’60s, early-’70s, and would have been influenced by the Folk revival: everything that happened in the early-’60s, through the ’60s in America with Woody Guthrie, and Pete Seeger, and The Kingston Trio, and The Mamas & the Papas. All that stuff then started flowing into rock and roll, and they were all heavily influenced by it too. Of course, part of that revival in the States was going back and looking at the roots of those folk traditions. Woody Guthrie becomes incredibly important again at that time, near his death [in 1967], with all that stuff that he wrote during the [Works Progress Administration]. The same thing was happening in parallel in Japan.

The continued occupation, in whatever form it was, was definitely a factor in Japan. Julian Cope has a book called Japrocksampler, which is a history of rock and roll in Japan. There was a Japanese band that hijacked a Korean airliner, and took it to North Korea as this sort of act of defiance and protest against the Japanese government. There was shit happening, for sure.

On father-daughter team Shintaro and Miya Ishida:

Shintaro was in some important early Country bands. Again, he’s about Charlie’s age. He wouldn’t have been old enough to go to war. He starts playing steel guitar, and guitar, and he was a really hot player. So he gets picked up by some of the biggest early Country & Western bandleaders. He had a rich history in touring, and was in some important bands, and then he gets his daughter Miya involved. She’s made trips to the States, and has a good career in Japan. Although, there’s not a lot of professional careers in Japan. I think that for a lot of these people, they live their day life as part of this collective society, and then their identity is really kind of defined as being a part of a Country & Western band, or a Bluegrass band at night. Japan has an interesting society. It’s this large densely-populated place, and people are expected to act as part of this massive social network. Then they distinguish themselves in very particular ways, and they’re very disciplined at it. America’s probably more of a nation of dabblers. But in Japan, people seem to pick what they’re into, or the groups that they’re going to be involved with, and they’re pretty dedicated.

Shintaro was in some important early Country bands. Again, he’s about Charlie’s age. He wouldn’t have been old enough to go to war. He starts playing steel guitar, and guitar, and he was a really hot player. So he gets picked up by some of the biggest early Country & Western bandleaders. He had a rich history in touring, and was in some important bands, and then he gets his daughter Miya involved. She’s made trips to the States, and has a good career in Japan. Although, there’s not a lot of professional careers in Japan. I think that for a lot of these people, they live their day life as part of this collective society, and then their identity is really kind of defined as being a part of a Country & Western band, or a Bluegrass band at night. Japan has an interesting society. It’s this large densely-populated place, and people are expected to act as part of this massive social network. Then they distinguish themselves in very particular ways, and they’re very disciplined at it. America’s probably more of a nation of dabblers. But in Japan, people seem to pick what they’re into, or the groups that they’re going to be involved with, and they’re pretty dedicated.

On musician Kazuhiro Inaba:

He lives in the greater Osaka area, and he has a school where they teach traditional music. I have not heard of very many of these, outside of university. So he ranges from traditional early Country, to Bluegrass, and he has a really amazing band. Everybody wears suits, and he has that 1950s kind of Bluegrass showman presence about him. He’s somebody I’m looking forward to getting to know better. I’ve kept in touch with him. But we only had about 20 minutes with him, and then we recorded a lot of live performance with him.

On musicologist Toru Mitsui:

He definitely wrote the most important things [on Japanese Country music] in English, and he’s also an English professor. He wrote this paper called Far Western. But he’s somebody I’ve only communicated with via email, so we’re trying to meet with him. I had a hard time finding him for a year-and-a-half. [Far Western] was next to impossible to find. It was in an obscure publication. I had to basically find him. He was on my Google alerts, and I saw that he had released a two-album set of traditional American music. So I tracked him down through this musicologist in Canada. And they tell this story of when [Mitsui] was in his maybe-early-30s, and he traveled in the Southern United States, because he wanted to find the origin and authorship of the song,

He definitely wrote the most important things [on Japanese Country music] in English, and he’s also an English professor. He wrote this paper called Far Western. But he’s somebody I’ve only communicated with via email, so we’re trying to meet with him. I had a hard time finding him for a year-and-a-half. [Far Western] was next to impossible to find. It was in an obscure publication. I had to basically find him. He was on my Google alerts, and I saw that he had released a two-album set of traditional American music. So I tracked him down through this musicologist in Canada. And they tell this story of when [Mitsui] was in his maybe-early-30s, and he traveled in the Southern United States, because he wanted to find the origin and authorship of the song,  “You Are My Sunshine” — which he considered to have particular importance in the hierarchy of Country music. So he travels to Georgia to try to find the origin and authorship of this song as sort of a personal journey. As a storyteller, I liked that thread of a personal journey. And I’m continually looking for these situations where these musicians are crossing back and forth over these boundaries as a result of being involved in this music.

“You Are My Sunshine” — which he considered to have particular importance in the hierarchy of Country music. So he travels to Georgia to try to find the origin and authorship of this song as sort of a personal journey. As a storyteller, I liked that thread of a personal journey. And I’m continually looking for these situations where these musicians are crossing back and forth over these boundaries as a result of being involved in this music.

The recordings of Alan Lomax were huge to Toru Mitsui. When the Anthology of American Folk Music came out, those were mind-blowing for a lot of those guys. And those are the recordings exactly that got [Mitsui] interested in Americana music. He played a Lead Belly song on this release that he did.

On Japanese Country musicians playing tours in America:

I think it’s incredibly energizing to come in contact with the source of the music. And they are performing kind of in a bubble there. So part of the Japanese nature, I think — especially the older Japanese — is that there is kind of a way to do it. So the music becomes somewhat static, because “This is the way we play ‘Blue Moon of Kentucky‘” or “This is the way we play ‘Take Me Back to Tulsa‘” But when the younger players come to the United States, they realize that the music is being transformed at a higher rate here. So there’s more creativity in how it’s being interpreted. And I think that was probably huge for a lot of those guys — Bluegrass guys in particular — when they were coming here in the early ’70s, making these pilgrimages to Kentucky and all over to hit these festivals.

What’s the Japanese approach to donning “Americana” apparel?

They definitely don’t do it subtly. Not being Japanese, I’m not really sure how they make those decisions. But it is pretty over the top. I think there’s definitely more flamboyance. I don’t know if that’s because it’s sort of a subculture, and they’re making these decisions when they’re purchasing from Sheplers online, or wherever they purchase their things through. So their sense of style is for whatever reason — and I’m not sure why — a little bit dramatized.

That’s compared to what you would see in Oklahoma City, where it is more a part of everyday wear. You know, it’s what you wear in the evenings, and the afternoons, or while you’re working. A lot of Country wear, it’s work wear. People wear a hat to keep their head cool. It has a real purpose. The purpose is very different [in Japan]. It’s an act of expression. Maybe due to that, it’s a little bit more flamboyant, a little more colorful.

People who make this decision to be involved in Country & Western music, and find this club, and go to this one bar — that’s part of their decision to define their identity. You’ll find a lot of these guys just go to the same bar. That’s their damn bar. And they’re not like, “Oh, so-and-so’s playing at the Nashville tonight.” They don’t go to the Nashville. It’s very cliquish, and it’s very insulated. You won’t see a lot of these players intermixing that much. There’s some degree of that, but not like you would see in Brooklyn, or Austin, or L.A.

From talking to Japanese people, there’s kind of a strange rivalry between the musicians. Once they’ve made their decision of “This is the group that I’m involved with”, to some extent that’s kind of set. There’s lots of Country dancing clubs, or just Country music fan clubs, and they will take tours to the United States. They’ll visit famous honky-tonks like Gilley’s and The Broken Spoke, and they’ll go to the grave of Hank Williams Sr. And they have business cards, and social cards. And at night, when they’re at their favorite honky-tonk, and you meet them, they’ll hand you their social card. It says that they’re a member of this group.

What are festivals like that you plan to cover on this upcoming trip?

I’ve been told that [Tajimi Mountain Time Bluegrass Festival] is the biggest Bluegrass festival in Japan. I’ve also been told that Japan has 40 Bluegrass festivals — which for a country that size, seems pretty impressive. Masuo Sasabe will play there with his band, called the Blueside of Lonesome. He was the first Japanese musician I ever met back in 2007, and he will be playing in the United States at the International Bluegrass Festival. We’re also producing a show with him in Tulsa, Oklahoma. Juta Sagai will also be at Tajimi. And just the fact that it’s supposed to be the largest Bluegrass festival made it an easy choice.

The [International Country Gold Festival] is the biggest Country event in Japan, and that’s of course Charlie Nagatani. We’ve got a lot of footage from the festival, but it’s more about continuing Charlie’s portrait. Charlie has a radio show that he’s been doing for over 30 years, called “Good Morning Sunshine”. So I want to go film this radio show. And we’ve gotten to know his son, and his wife some. So we just want to do more day-in-the-life with Mr. Nagatani.