(Publisher’s Note: Originally published in March of 2014)

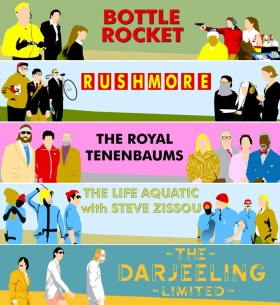

Wes Anderson is once again taking bright colors, deadpan humor, a completely ridiculous story, and recruited friends Jason Schwartzman, Bill Murray, and Owen Wilson to appear in tiny-but-amusing roles — and I couldn’t be happier. For almost 20 years, Wes has been working to create visually-stunning films, with arguably the best movie soundtracks in cinema history. His newest film, Grand Budapest Hotel has been called his best work since his breakthrough, Rushmore. Budapest Hotel does not break new ground for Anderson, or feature a remarkably-different plot or style. By now, Fans know what they are getting into, and that’s simply what we like. Anderson’s films have a certain look and feel that can’t really be matched or compared. Everything is bright, oddly-symmetrical, and usually whimsical. A mere poster is enough to identify a Wes Anderson film. He has created his own world in cinema, using nothing more than a quirky voice, retro tastes, and an influence from French “New Wave” films of the 1960s. Different cultures of the world have been displayed on screen since the birth of film. And yet, Wes Anderson is one of the few directors who has created his own expansive on-screen culture, which has translated into both commercial success and a loyal cult following.

Wes Anderson is once again taking bright colors, deadpan humor, a completely ridiculous story, and recruited friends Jason Schwartzman, Bill Murray, and Owen Wilson to appear in tiny-but-amusing roles — and I couldn’t be happier. For almost 20 years, Wes has been working to create visually-stunning films, with arguably the best movie soundtracks in cinema history. His newest film, Grand Budapest Hotel has been called his best work since his breakthrough, Rushmore. Budapest Hotel does not break new ground for Anderson, or feature a remarkably-different plot or style. By now, Fans know what they are getting into, and that’s simply what we like. Anderson’s films have a certain look and feel that can’t really be matched or compared. Everything is bright, oddly-symmetrical, and usually whimsical. A mere poster is enough to identify a Wes Anderson film. He has created his own world in cinema, using nothing more than a quirky voice, retro tastes, and an influence from French “New Wave” films of the 1960s. Different cultures of the world have been displayed on screen since the birth of film. And yet, Wes Anderson is one of the few directors who has created his own expansive on-screen culture, which has translated into both commercial success and a loyal cult following.

Grand Budapest Hotel follows Gustave (played by a fabulous Ralph Fiennes), a legendary concierge at a secluded-but-fancy hotel. He spends his days training a new lobby boy, and sleeping with the hotel’s oldest guests. When one old lady dies from mysterious circumstances, Gustave learns he has inherited a priceless painting known as “Boy with Apple”. Many forces try and stop him from inheriting the picture, causing a journey full of laughs and bizarre situations. Odd plot? Yes! It’s one that only the talented Mr. Anderson could think up, and features familiar faces from his previous films, as well as stunning shades of color and unusual fonts. In creating his own setting (the European Republic of Zubrowka), Anderson takes obvious inspiration from Switzerland and Germany — with the prior’s snowy mountainous terrain and the latter’s Bavarian undertones. In this fictional land, a war is creating problems for the protagonists, and raising the stakes for the rest of our characters.

So why would Wes make up a fictional country, when it could just as easily be Austria or some similar European place? Because it gives him freedom to do whatever he wants. The story finds itself without historical limits — or any our world’s realistic ones for that matter. Anderson’s characters are often outlandish and exaggerated, but they fit because of the setting they are given. What filmmaker wouldn’t want to create their own world, so as to be free to do whatever they want? This isn’t the first time he’s written a fictional setting either. In the Oscar-nominated Moonrise Kingdom, the characters live on the East Coast island of New Penzance. On “the map” it is part of New England, and Anderson’s  style gives life to the island with quirky architecture, beautiful beaches, and over-the-top 1960s clothing. The look and feel of the island is what gives the film such a unique and memorable touch.

style gives life to the island with quirky architecture, beautiful beaches, and over-the-top 1960s clothing. The look and feel of the island is what gives the film such a unique and memorable touch.

Anderson has used real places for his films as well, including New York City for The Royal Tenenbaums and Texas for Bottle Rocket. But they still contain the odd and distinctive look typical of Anderson’s movies. As for the deep sea adventure The Life Aquatic with Steve Zissou and the stop-motion Fantastic Mr. Fox, there’s no telling if the locations are real, but only Anderson could have brought them to life on screen.

Of course, Wes isn’t the only director with his own unique style and cinematic worlds. Tim Burton has been known as the gothic king of cinema, with his dark and often-supernatural settings and moods. Whether it’s the creepy suburbs of Beetlejuice or Edward Scissorhands, the bleak Gotham City of Batman, or the straight-up gothic horror of Sleepy Hollow and Sweeney Todd, his films are always recognizable. The themes of conformity or good-vs-evil are often showcased through landmarks. Though it’s rare for Tim to make up a world from scratch — save The Nightmare Before Christmas — all of his settings are exaggerated and belong to a unique vision that he has become famous for.

Quentin Tarantino has created a world of criminals and ultra-violence. Though his last two films have been more period pieces than crime capers, Quentin still showcases brutal killings and stellar dialogue between characters. His early films from the ’90s, like Reservoir Dogs, Pulp Fiction, and Jackie Brown all have the same gritty look and focus on criminals talking about mundane things like burgers and Madonna songs through snappy dialogue. Quentin doesn’t employ very unique settings, but he populates them with interlocking characters (like the Vega Brothers) who appear throughout his films, making them easily identifiable. He did however rewrite history with Inglourious Basterds.

Finally, Kevin Smith is certainly a filmmaker who has created his own culture and unique style. It may sound like an odd choice, but he did set many of his movies in “View Askew”, a fake universe where people like Jay and Silent Bob, Holden McNeil, Banky Edwards, and Dante Hicks slack off. These lower-class characters do the same things in all of Smith’s movies: talk about women, comic books, how work sucks, and how good weed is. From Clerks to Dogma, this world is basically ours, but filled with odd people who all seem to hang out. To date, Smith has made six films set in the Viewaskewniverse, with a seventh (Clerks 3) in the works.

These filmmakers and many more are easily identifiable because of their worlds, no matter how simple or extravagant they may me. Within them, the filmmaker’s voice and style can come out and tell stories that are fresh and unique. The results are a solid fan base who identify with the vision on screen, and admire the bold territory the director is exploring. Wes Anderson happens to be one of my most favorite writer/directors. No other filmmaker has a body of work to match the look, setting, or even plot of his movies. The same goes for Tim Burton and Quentin Tarantino. We have seen Los Angeles, London, or Tokyo many times on screen. Yet these filmmakers dare to dream up unknown lands, and give new twists to the familiar. I urge you to check out a Wes Anderson film, if you haven’t already, if only to admire how wonderfully bizarre it looks — and definitely book passage to the fictional land of Zubrowka and the Grand Budapest Hotel.