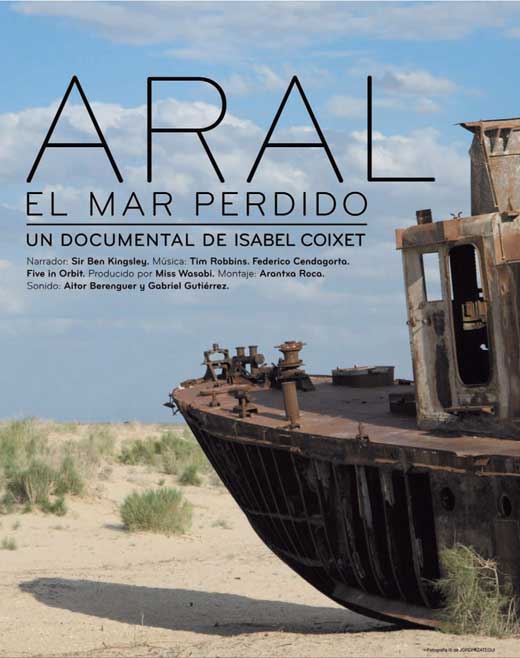

Who: Isabel Coixet is a Spanish filmmaker based in Barcelona. In 2010, she collaborated with Spanish nonprofit We Are Water for the organization’s first initiative aimed at improving the management of water resources around the world. Fascinated by the Aral Sea from afar since discovering it on a school map in her youth, Coixet journeyed to Uzbekistan to shoot a documentary about its drastic reduction over the past 50 years — something We Are Water describes as “one of the greatest environmental disasters in history.” The drying up goes back to the 1950s, when a large Soviet canal siphoned off 1/3 of the water supplied by the Amu Darya River, in order to irrigate local cotton fields. Through a combination of mismanagement and inefficient irrigation techniques, the Aral’s water supply continued to dwindle, and the inland ocean began to dry up. Today it possesses only half of its original surface area, and 75% of its old volume, and We Are Water finds that “95% of the nearby reservoirs and wetlands have become deserts and more than 50 lakes from deltas with a surface area of 60,000 hectares have dried up.” Coixet shot in and around the former-port of Muynak, whose fishing industry-based economy was destroyed by the retreating coastline and mounting pollution of the South Aral. Her footage became the 25-minute short film, Aral: The Lost Sea, which premiered at the 2010 San Sebastian Film Festival. Narration was provided by actor Ben Kingsley, who Coixet directed in Elegy, and soundtrack music was provided by Tim Robbins, who was in Coixet’s The Secret Life of Words. Camera in The Sun spoke to Coixet for a May 2014 interview about the Aral Sea, the environmental conditions she found in Muynak, and her thoughts on using filmmaking skills for advocacy projects.

Who: Isabel Coixet is a Spanish filmmaker based in Barcelona. In 2010, she collaborated with Spanish nonprofit We Are Water for the organization’s first initiative aimed at improving the management of water resources around the world. Fascinated by the Aral Sea from afar since discovering it on a school map in her youth, Coixet journeyed to Uzbekistan to shoot a documentary about its drastic reduction over the past 50 years — something We Are Water describes as “one of the greatest environmental disasters in history.” The drying up goes back to the 1950s, when a large Soviet canal siphoned off 1/3 of the water supplied by the Amu Darya River, in order to irrigate local cotton fields. Through a combination of mismanagement and inefficient irrigation techniques, the Aral’s water supply continued to dwindle, and the inland ocean began to dry up. Today it possesses only half of its original surface area, and 75% of its old volume, and We Are Water finds that “95% of the nearby reservoirs and wetlands have become deserts and more than 50 lakes from deltas with a surface area of 60,000 hectares have dried up.” Coixet shot in and around the former-port of Muynak, whose fishing industry-based economy was destroyed by the retreating coastline and mounting pollution of the South Aral. Her footage became the 25-minute short film, Aral: The Lost Sea, which premiered at the 2010 San Sebastian Film Festival. Narration was provided by actor Ben Kingsley, who Coixet directed in Elegy, and soundtrack music was provided by Tim Robbins, who was in Coixet’s The Secret Life of Words. Camera in The Sun spoke to Coixet for a May 2014 interview about the Aral Sea, the environmental conditions she found in Muynak, and her thoughts on using filmmaking skills for advocacy projects.

How did you become involved with We Are Water, and the Aral Sea project?

I know people who work at We Are Water. They were starting, and they asked me, “So is there something related to water, or the lack of it, that you want to do?” And since I was collecting all these fragments of information and press clippings about the Aral Sea, I thought, “OK, well I want to go there and see how it is, and make a documentary you can use for your foundation.” They said yes, and that was the beginning of it. But for me, the obsession with the Aral Sea was in the last 20 years. I was always trying to scan for information about what happened there, why, and how people are coping. So this was a very good opportunity to do something.

I know people who work at We Are Water. They were starting, and they asked me, “So is there something related to water, or the lack of it, that you want to do?” And since I was collecting all these fragments of information and press clippings about the Aral Sea, I thought, “OK, well I want to go there and see how it is, and make a documentary you can use for your foundation.” They said yes, and that was the beginning of it. But for me, the obsession with the Aral Sea was in the last 20 years. I was always trying to scan for information about what happened there, why, and how people are coping. So this was a very good opportunity to do something.

Why did you choose to shoot in Muynak?

I read lots of articles, and I thought Muynak was a very good start for a trip to what is left of the Aral Sea. In fact, they have this place in the hills where you can see where the sea was supposed to be, and was very attractive. Also, the fact all these ships were surrounded by sand. And when we went there, we didn’t have any script. We thought, “We’ll go there, we’ll talk to people, and then see as we go what we do.” There are many more documentaries that really bathe in scientific facts. But for me, the important thing was the experience. How people who grow with the sea cope with the lack of it.

Muynak is a ghost town. I think they live with some kind of little tiny money from the government. But they do nothing. There’s really nothing to do. Literally, nothing. And I don’t know how they survive, really. There’s a few tourists. I guess some people like me go. But we didn’t cross paths with anyone at that time.

There was a huge factory where they were canning sardines and anchovies and tuna. The documentary is about the absence of the sea. That’s what was striking to me. What was interesting too was how many people think the sea will come back. And they have really convinced themselves without any proof. Because we know now how the Aral Sea disappeared, and why. But when you talk to these people — and we talk with one in this documentary — they are like, “Yeah, we had the boats outside the house, and from the window I was listening to waves and the fish. It disappeared, but it will come back.” OK, but you have to do something for it. But people don’t want to listen.

[Abandoned boats] are nearby Muynak, because it was where the harbor was. I guess the sea was disappearing at a speed the owners of these boats never imagined was going to happen. But they are there, and the people who worked in these ships go everyday to see them — to pay their respects, I guess. They are there, and then they talk to you about what life was on the ships, and how meaningful being sailors was for them, and how they grew up in this sailor culture. Then suddenly, it disappeared.

[The film uses] real footage from the Aral Sea from the ’60s. We found it, and it was a way for me to say “Listen, this desert you are seeing, it was a sea then.” I thought the most powerful way was to show this was real footage from the 60s.

What was the environmental situation like?

The whole time we felt like the people at the end of the Planet of the Apes, when they found the Statue of Liberty. It was perplexity. Because when you’re there, and you see the place where the sea used to be, you think that can happen where we live. It’s like living a tiny apocalypse, and you feel that in your bones and in your skin the whole time you’re there. Especially because we came from Barcelona, and we live in a city  where the sea is really important, and we have faith in the sea. So if we keep doing all these things to the environment, that’s what’s gonna happen with the Mediterranean. At the same time, since the Aral Sea disappeared because of a series of mistakes, they made it disappear on purpose. You say to yourself, “So these human mistakes, we keep doing them. So what’s going to happen with the rivers where we live, and the sea, and the kind of life the sea provides?”

where the sea is really important, and we have faith in the sea. So if we keep doing all these things to the environment, that’s what’s gonna happen with the Mediterranean. At the same time, since the Aral Sea disappeared because of a series of mistakes, they made it disappear on purpose. You say to yourself, “So these human mistakes, we keep doing them. So what’s going to happen with the rivers where we live, and the sea, and the kind of life the sea provides?”

[The Aral coast] is very strange, because there’s no birds, there’s no seaweed. There’s nothing. It’s very quiet. It’s like a sea graveyard for me, and I think for all of us. Because the guides from Uzbekistan who came with us, they were saying, “There’s no problem. You can swim there.” And I don’t think it’s a good thing for you to swim there. I didn’t do it.

We mostly drank warm beer, because it was the only thing. And we took lots of water in plastic bottles from Tashkent. And also, in Muynak, they don’t have tap water. You cannot even take a shower in this place.

Why about the map image of the Aral attracted you as a child?

That image of that map was so vivid. I even remember the colors where they pictured Canada or the States. I learned and repeated all the capitals of the world, and that doesn’t happen any more. Because people don’t give a shit what the capital of Mozambique is, or other countries. This culture of names and knowing things by heart, it’s disappeared. So for me, this map with all these countries and all these colors — I still have this image of Mongolia being a green country, just because Mongolia was green on the map at my school. And all these things mix with the sound of some words like “Aral”. To me, Aral was a helpful word. I have this obsession about how words give you impressions, and some words are so right for some objects or places or people.  And some others, they don’t. But for me, Aral was a very evocative word. Aral was something nice and blue and fresh. Probably since I was five years old, it stayed with me. I cannot explain it in a very rational way. But some of the things I’ve done in my life, they have a strange relationship with these first impressions of when I was a kid, when you don’t really know how to explain things. But some color, plus some words, they mean something. Probably in some ways, completely different from what the reality is. But that reality is more real for you than the reality reality.

And some others, they don’t. But for me, Aral was a very evocative word. Aral was something nice and blue and fresh. Probably since I was five years old, it stayed with me. I cannot explain it in a very rational way. But some of the things I’ve done in my life, they have a strange relationship with these first impressions of when I was a kid, when you don’t really know how to explain things. But some color, plus some words, they mean something. Probably in some ways, completely different from what the reality is. But that reality is more real for you than the reality reality.

We did an exhibition dedicated to schools where boys and girls from schools came to the exhibition, they see the documentary, they ask questions. Ae have all these animations, and all this structure to show in a way people can understand easily what has happened with the Aral Sea. For me, I had the opportunity to do this thing, and I’m really happy I did it. I don’t know what will come out with it. I think one of the things we can say when we show these documentaries, people can trace where the Aral Sea is, and where Uzbekistan is. And you know, that’s something. It’s not much, but that’s something.

Do you want to see more filmmakers use their skills for advocacy projects?

I think you have to do what you have to do when you feel compelled to do it. I did a piece [Marea Blanca, or “White Tide”] about another ecological catastrophe in the North of Spain that happened 10 years ago, when a ship called “Prestige” collapsed along the northern coast. For years, some parts of the coast were completely covered in oil. And for me, it was a way to do a documentary about what happened 10 years after this thing. But I did it because I felt compelled to do it. Not because I thought it was my duty or anything. Also, I did a documentary [Escuchando al juez Garzón, or “Listening to Garzón”] about a judge who was being judged in Spain, because I was convinced he was innocent. And I don’t want to say you have to do it, and it’s your duty. But as a filmmaker, if you felt compelled to do a piece or a documentary or a short or a medium film, why not? To me, that was rewarding. It’s a way to touch reality from another point of view. And I enjoy immensely doing these things, and I hope I will do more in the future.