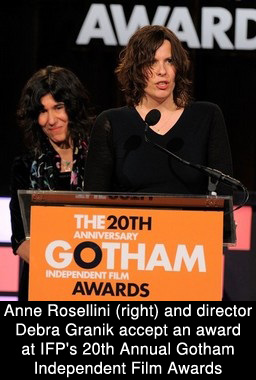

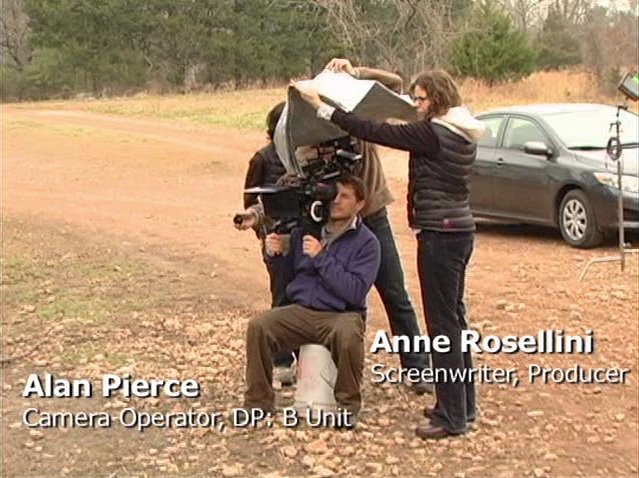

Who: Anne Rosellini is a New York City-based writer/producer who formerly worked from Seattle, Washington, where she founded the 1 Reel Film Festival in 1996 (now run through the Seattle International Film Festival). In 2004, she produced the upstate New York-shot Down to the Bone for writer/director Debra Granik. She later scouted locations in Astoria, Oregon for filmmaker Dan Gildark’s 2007 film, Cthulhu, before collaborating with Granik again as producer/co-writer of 2010’s Missouri-shot Winter’s Bone. The film has garnered critical praise for it’s portrayal of a young girl’s (Jennifer Lawrence) hardscrabble existence in the Ozark Mountains, wherein she serves as parent to her younger siblings in the absence of their missing father.

Who: Anne Rosellini is a New York City-based writer/producer who formerly worked from Seattle, Washington, where she founded the 1 Reel Film Festival in 1996 (now run through the Seattle International Film Festival). In 2004, she produced the upstate New York-shot Down to the Bone for writer/director Debra Granik. She later scouted locations in Astoria, Oregon for filmmaker Dan Gildark’s 2007 film, Cthulhu, before collaborating with Granik again as producer/co-writer of 2010’s Missouri-shot Winter’s Bone. The film has garnered critical praise for it’s portrayal of a young girl’s (Jennifer Lawrence) hardscrabble existence in the Ozark Mountains, wherein she serves as parent to her younger siblings in the absence of their missing father.

What’s the value of shooting a feature film on location?

Debra said this the other day. It’s like people want to see films about America, and yet films about America are usually shot in New York, or L.A, or in “Nowheresville” or “Everymansland” or the kind of place that can stand in for any place. And it’s like, “No, where are the films about America?” I mean, there are amazing small  towns and pockets that are very specific and real and have cultural individuality, believe it or not. I almost feel like it’s our duty as filmmakers to explore that and reveal that to the rest of the world as a document of our time and the country that we live in. This is a big, big country and there’s a lot of amazing people and places and things, and it’s a crime to not explore that in film. Granted, most films are about happy rich people, and film is supposed to be some big escape. Those aren’t the kinds of films we’re trying to make.

towns and pockets that are very specific and real and have cultural individuality, believe it or not. I almost feel like it’s our duty as filmmakers to explore that and reveal that to the rest of the world as a document of our time and the country that we live in. This is a big, big country and there’s a lot of amazing people and places and things, and it’s a crime to not explore that in film. Granted, most films are about happy rich people, and film is supposed to be some big escape. Those aren’t the kinds of films we’re trying to make.

How many Seattle-shot shorts made it into the 1 Reel Film Festival when you were there?

Those films were from mostly the coasts. I mean, most short films are made by film students and from directors trying to make a calling card. They were mostly coming out of New York and L.A., quite frankly, and we also did international films. I would say there was a very small section each year of local films.  I can think of only a couple of films that I really truly love from the Northwest. And those were from a guy named John Jeffcoat, whose early work I showed, and also a guy named Jay Rosenblatt, who’s a brilliant documentary filmmaker out of San Francisco. I would say 99% of the films I showed were from everywhere but Seattle — everywhere but Washington.

I can think of only a couple of films that I really truly love from the Northwest. And those were from a guy named John Jeffcoat, whose early work I showed, and also a guy named Jay Rosenblatt, who’s a brilliant documentary filmmaker out of San Francisco. I would say 99% of the films I showed were from everywhere but Seattle — everywhere but Washington.

Everyone really quickly sort of bypassed us for Vancouver, because the state of Washington never did get it together and have an aggressive tax incentive. So, the ten solid years I was living and working in Seattle, there was almost absolutely no scene that I knew of. I mean, I worked on some very humble projects as coordinator when I was in film production, but nothing that ever sort of went anywhere.

What does Washington State’s landscape offer to filmmakers who want to shoot on location?

I feel like aesthetically and photographically there are two films — Snow Falling on Cedars and Twilight — have captured some of the amazing beauty. Both of those sort of focused on the rain forest area, but Washington State is such a diverse state. I mean, there’s desert. There’s mountains. There’s rain forests. There’s prairie. There’s coast. It’s a very diverse place to shoot. And then, of course, there are places like the rain forest, which are so unique and lush and beautiful that it would be a dream. There’s also a lot of weird dieing towns, and there’s Indian reservations. There’s so much photogenic stuff going on in the state, and it’s a crime that it doesn’t get utilized more.

Twilight — have captured some of the amazing beauty. Both of those sort of focused on the rain forest area, but Washington State is such a diverse state. I mean, there’s desert. There’s mountains. There’s rain forests. There’s prairie. There’s coast. It’s a very diverse place to shoot. And then, of course, there are places like the rain forest, which are so unique and lush and beautiful that it would be a dream. There’s also a lot of weird dieing towns, and there’s Indian reservations. There’s so much photogenic stuff going on in the state, and it’s a crime that it doesn’t get utilized more.

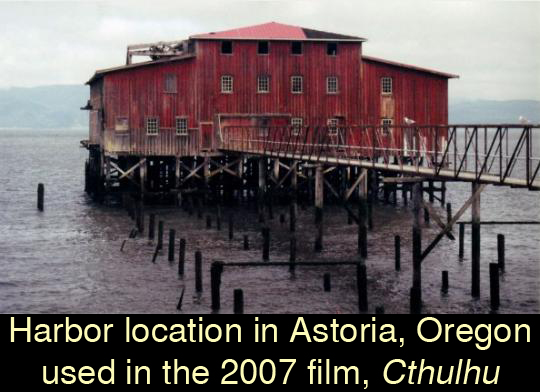

What visually appealed to you about Astoria, Oregon while scouting locations for Cthulhu?

It’s got a very specific architecture. It was developed by the Astors of New York, and so there’s a very specific period architecture going on in many of the homes, because they thought at one point that it was going to be some huge port. But it sort of died really quickly, and the former glory from that era is still there, and a lot of people have moved down from Seattle, or over from Portland to refurnish those houses.  It was that specific look that the creators of Cthulhu were interested in. And, of course, it sits right on the water. There’s this amazing bridge that goes from the state of Washington to the state of Oregon. So, it’s incredibly scenic and it has this amazing port with all these creepy old docks and net sheds that were just sort of there. I mean, the town itself was incredibly helpful to us. I’ve always found it’s very easy and enjoyable usually to make a film in any place other than like New York or L.A. It doesn’t happen often and people are often just very friendly and excited and interested and willing to help, as was the city of Astoria.

It was that specific look that the creators of Cthulhu were interested in. And, of course, it sits right on the water. There’s this amazing bridge that goes from the state of Washington to the state of Oregon. So, it’s incredibly scenic and it has this amazing port with all these creepy old docks and net sheds that were just sort of there. I mean, the town itself was incredibly helpful to us. I’ve always found it’s very easy and enjoyable usually to make a film in any place other than like New York or L.A. It doesn’t happen often and people are often just very friendly and excited and interested and willing to help, as was the city of Astoria.

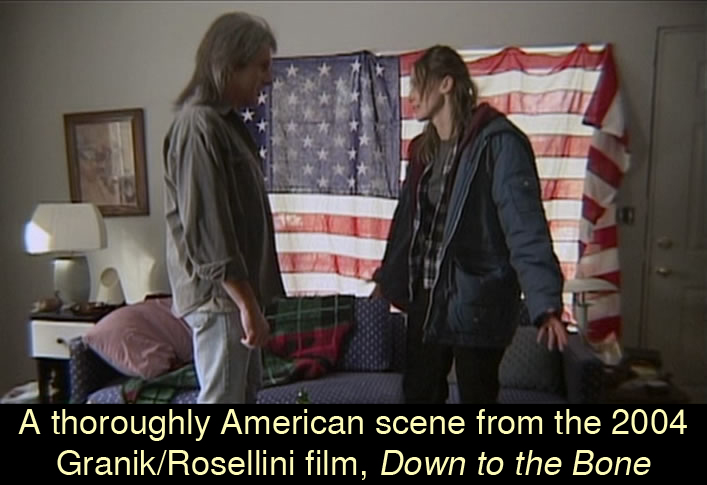

Why was Down to the Bone filmed in upstate New York?

When Debra was attending NYU graduate school, she met a woman in upstate New York who she started documenting. And that evolved into a seven-year-long documentation of this woman’s life.  And she ultimately made a short film that starred the woman, but was sort of a narrative that won the Sundance short film award. She was invited to the lab to create a feature script, which is when I came on board, shortly after she’d done a couple of versions of the feature script. So, the whole film was based in upstate New York, because that’s where the inspiration for this film lived.

And she ultimately made a short film that starred the woman, but was sort of a narrative that won the Sundance short film award. She was invited to the lab to create a feature script, which is when I came on board, shortly after she’d done a couple of versions of the feature script. So, the whole film was based in upstate New York, because that’s where the inspiration for this film lived.

Down to the Bone was such a humble effort, I don’t even know if there was a tax incentive at that point. It was 2003. There probably was, but it was the first film I ever produced. We tried to get financing. I sent it out there to everyone I knew or could get my hands on whose filmography I thought was apropos — like the kinds of producers that would want to work on a film like this — and we just got rejected by everybody. So, ultimately we were able to scrape together — through basically a couple of friends with money — enough money to make it. I mean, it was literally a $200,000 film, so we were so under the radar. It wasn’t a union shoot. There was no tax incentive money going there. It was just a very scrappy kind of shoot.

and we just got rejected by everybody. So, ultimately we were able to scrape together — through basically a couple of friends with money — enough money to make it. I mean, it was literally a $200,000 film, so we were so under the radar. It wasn’t a union shoot. There was no tax incentive money going there. It was just a very scrappy kind of shoot.

Debra was interested in definitely the working class part of upstate — the people who live there year around. Things were really just starting to kind of boom up there. We shot in Saugerties. We shot in Woodstock. It was just very much like people maybe who once lived in a city, or were from bigger places, but found themselves very much caught in between a suburb and an urban world. There’s a lot of sprawl there.  There’s a lot of isolation there. That film dealt with addiction. It’s like, what do you do when there’s sort of no place to go? And in the photography I think, if you’ve seen the film, you see that we found a lot of beauty in the snow drifts and the huge massive parking lots and the many, many humble neighborhoods where we filmed. That’s the upstate that our characters were from, and that’s the upstate that we focused on and wanted to film.

There’s a lot of isolation there. That film dealt with addiction. It’s like, what do you do when there’s sort of no place to go? And in the photography I think, if you’ve seen the film, you see that we found a lot of beauty in the snow drifts and the huge massive parking lots and the many, many humble neighborhoods where we filmed. That’s the upstate that our characters were from, and that’s the upstate that we focused on and wanted to film.

Was there a financing advantage to shooting Winter’s Bone on location in Missouri?

It’s written by an Ozarks author named Daniel Woodrell, and the story very much takes place in the Ozarks, which is what he writes very beautifully about. And so, in our minds we never were planning to film anywhere other than the Ozarks. We’d never been there, and it felt daunting to us. But reading his description of the Ozarks peaked our interest and made us very curious and excited about making a film there. So, we went there to meet him and to see some of the inspiration for the film, and see if what we read about was really there. And we fell madly in love. We couldn’t wait to make a film there, basically.

It’s written by an Ozarks author named Daniel Woodrell, and the story very much takes place in the Ozarks, which is what he writes very beautifully about. And so, in our minds we never were planning to film anywhere other than the Ozarks. We’d never been there, and it felt daunting to us. But reading his description of the Ozarks peaked our interest and made us very curious and excited about making a film there. So, we went there to meet him and to see some of the inspiration for the film, and see if what we read about was really there. And we fell madly in love. We couldn’t wait to make a film there, basically.  You know, it was bandied about a couple times, “Oh, should we go someplace else with a better tax incentive?” But we never really took it seriously, because Missouri has a pretty aggressive tax incentive, and also ultimately we just knew we had to film in the Ozarks with people from the Ozarks. That’s the way Debra likes to work, and that’s the way I like to work. You take what you have and you use it. You revel in the lushness and the beauty and the richness of the culture that is there, and you exploit it in the best way possible. Why would you ever want to strip that away and start over on a sound stage somewhere?

You know, it was bandied about a couple times, “Oh, should we go someplace else with a better tax incentive?” But we never really took it seriously, because Missouri has a pretty aggressive tax incentive, and also ultimately we just knew we had to film in the Ozarks with people from the Ozarks. That’s the way Debra likes to work, and that’s the way I like to work. You take what you have and you use it. You revel in the lushness and the beauty and the richness of the culture that is there, and you exploit it in the best way possible. Why would you ever want to strip that away and start over on a sound stage somewhere?

The film commission was wonderful there. The very first thing they did was bring us down for three days, and they got us a location scout. It was wonderful. They put us up, and we told them what kind  of locations we were looking for and they tried to help us find those. Ultimately, it was through that location scout that we met the person that really did become the fixer for us in the Ozarks, which is kind of a hard place to penetrate. Strangers from New York can’t just sort of show up on people’s private land and try to shoot a film there. So, the Missouri Film Commission played a big role initially in getting us to the right kind of area — the right zip code, if you will. And as for financing, we worked with Alix Madigan from Anonymous Content, who shopped the film around quite a bit for a couple of years while Debra and I were developing the script and finding the locations and doing research. And we came very close with a couple of production companies.

of locations we were looking for and they tried to help us find those. Ultimately, it was through that location scout that we met the person that really did become the fixer for us in the Ozarks, which is kind of a hard place to penetrate. Strangers from New York can’t just sort of show up on people’s private land and try to shoot a film there. So, the Missouri Film Commission played a big role initially in getting us to the right kind of area — the right zip code, if you will. And as for financing, we worked with Alix Madigan from Anonymous Content, who shopped the film around quite a bit for a couple of years while Debra and I were developing the script and finding the locations and doing research. And we came very close with a couple of production companies.  One in particular, but ultimately they kind of backed out at the last minute, so we went looking for private equity. We kind of felt like we just needed somebody to dive in with us, and even though it was going to be half the budget we originally proposed, we wanted to make it on our own terms and were able to find a private investor who was open to that as well, because of the first film that we did. So, we ran with that. We were like, “We don’t care if it’s half the budget,” and in the end it was a big blessing in disguise. We had total creative control, and we got a lot of time to research, and that research

One in particular, but ultimately they kind of backed out at the last minute, so we went looking for private equity. We kind of felt like we just needed somebody to dive in with us, and even though it was going to be half the budget we originally proposed, we wanted to make it on our own terms and were able to find a private investor who was open to that as well, because of the first film that we did. So, we ran with that. We were like, “We don’t care if it’s half the budget,” and in the end it was a big blessing in disguise. We had total creative control, and we got a lot of time to research, and that research  helped prepare us to make a great film.

helped prepare us to make a great film.

We came away with really great relationships down there. We shot the film on live locations in people’s houses, on their land with their livestock. We even cast some of them. And had we gotten financed immediately, we never would have had time to develop those relationships. And I think it did add a richness and authenticity to the film that would not have been there otherwise. And also having a lower budget really helped us remain scrappy and kind of true to ourselves.

How did those strong relationships affect your approach to portraying rural Ozarks residents?

I think mainly what we were concerned about was not perpetuating negative stereotypes about the area. And that was a big concern of ours. I think that the bottom line is everybody read the script and read the book and knew what we were trying to do. And I think Debra tried to balance what was in the book with what people actually brought to the role, and tried to find a balance that felt right for them and right for the film. Truly, we were driving around, and we were trying to understand like, “Why is there so much junk in this person’s yard?” And how can we show this without perpetuating this really negative stereotype.

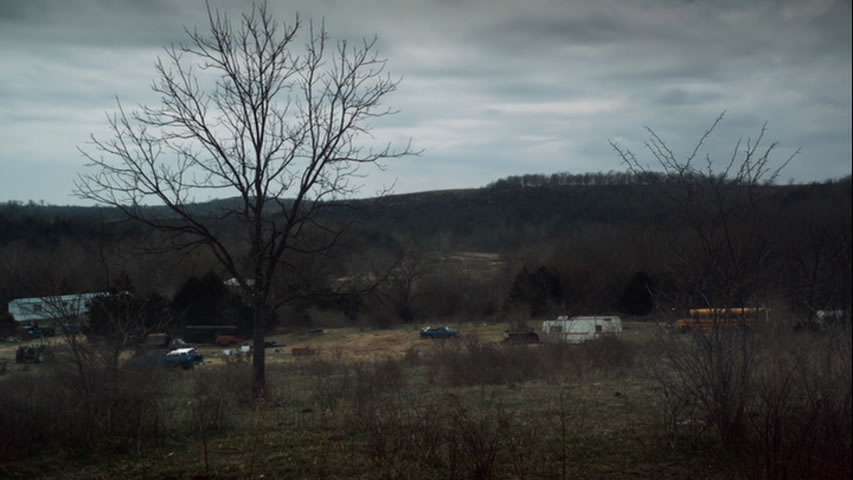

I think mainly what we were concerned about was not perpetuating negative stereotypes about the area. And that was a big concern of ours. I think that the bottom line is everybody read the script and read the book and knew what we were trying to do. And I think Debra tried to balance what was in the book with what people actually brought to the role, and tried to find a balance that felt right for them and right for the film. Truly, we were driving around, and we were trying to understand like, “Why is there so much junk in this person’s yard?” And how can we show this without perpetuating this really negative stereotype.  Because over the three years that we were down there meeting people and learning about how they lived – and frankly being schooled much more on our end than they were on their end. We started to understand, well, you know what – there’s no garbage pickup, and people like to reuse things and they have tons of land. I mean, there’s like ten reasons why people have stuff on their land. Their nearest neighbor lives ten miles away. No one ever visits. You know, we started to understand the complexities of life there and how hard it was for these people to make a living and stay afloat and how hard they work.

Because over the three years that we were down there meeting people and learning about how they lived – and frankly being schooled much more on our end than they were on their end. We started to understand, well, you know what – there’s no garbage pickup, and people like to reuse things and they have tons of land. I mean, there’s like ten reasons why people have stuff on their land. Their nearest neighbor lives ten miles away. No one ever visits. You know, we started to understand the complexities of life there and how hard it was for these people to make a living and stay afloat and how hard they work.  They were so trusting of us, and so giving, and such good, good people. We felt really terrified, like, “Oh my god, we can’t betray them for the sake of the story.” And I think that Daniel did a good enough job of making a really wonderful heroine. I mean, Ree is a good person. Her family may be entangled in some pretty dubious business, but at the heart of it she’s got great family values. She wants what’s best for her family, and we could always stand behind that.

They were so trusting of us, and so giving, and such good, good people. We felt really terrified, like, “Oh my god, we can’t betray them for the sake of the story.” And I think that Daniel did a good enough job of making a really wonderful heroine. I mean, Ree is a good person. Her family may be entangled in some pretty dubious business, but at the heart of it she’s got great family values. She wants what’s best for her family, and we could always stand behind that.