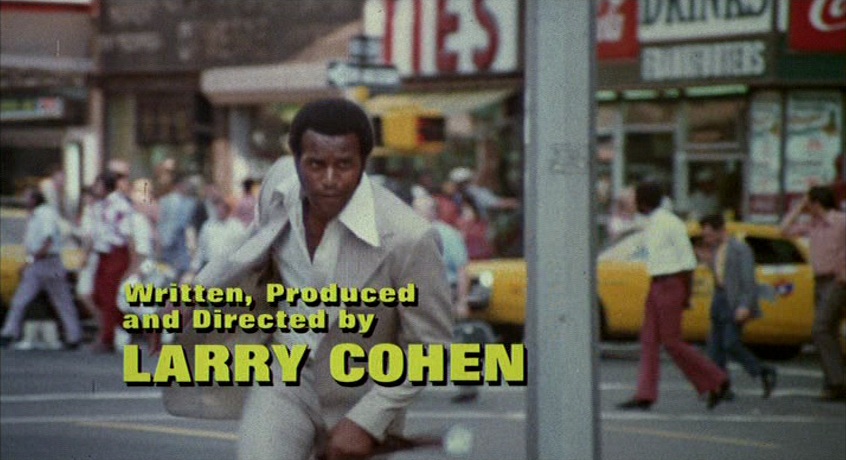

Who: Larry Cohen is a veteran filmmaker who grew up in Bronx, New York before embarking on a long career that included several New York City-shot films. Two of those films starred former-NFL defensive back Fred Williamson, who was born and raised in Gary, Indiana. 1973’s Black Caesar charted Williamson’s bloody rise as Tommy Gibbs to the top of New York’s underworld, while 1973’s Hell Up in Harlem was an action-packed sequel that was quickly shot in both New York and Los Angeles, and released later that same year. In 1996, Cohen and Williamson’s third collaboration, Original Gangstas was released, and was shot on location in Williamson’s hometown of Gary. The film’s plot hinged on the city’s infamous identity at that time as one of America’s most crime-ridden municipalities. Camera In The Sun talked to Cohen about his three films with Williamson, to what degree his portrayals of New York City and Gary reflected their grim socioeconomic plights, and the challenges he faced in shooting on location — as with this taxi scene, shot without any permits on the streets of Manhattan:

Who: Larry Cohen is a veteran filmmaker who grew up in Bronx, New York before embarking on a long career that included several New York City-shot films. Two of those films starred former-NFL defensive back Fred Williamson, who was born and raised in Gary, Indiana. 1973’s Black Caesar charted Williamson’s bloody rise as Tommy Gibbs to the top of New York’s underworld, while 1973’s Hell Up in Harlem was an action-packed sequel that was quickly shot in both New York and Los Angeles, and released later that same year. In 1996, Cohen and Williamson’s third collaboration, Original Gangstas was released, and was shot on location in Williamson’s hometown of Gary. The film’s plot hinged on the city’s infamous identity at that time as one of America’s most crime-ridden municipalities. Camera In The Sun talked to Cohen about his three films with Williamson, to what degree his portrayals of New York City and Gary reflected their grim socioeconomic plights, and the challenges he faced in shooting on location — as with this taxi scene, shot without any permits on the streets of Manhattan:

How familiar were you with Harlem, and what was it like while filming Black Caesar there?

Well, I’d grown up in New York City and went to college at City College, which is located in Harlem. I always lived in New York, and then I came out to California after I’d had an extensive career in television — particularly in a lot television shows that originated in New York. First with live television, which originated usually at NBC or CBS in New York City. Then later on with shows like The Defenders, which were film shows that were filmed up in the uptown studios in New York City, and The Nurses, which was another show that was filmed in New York. Then I created a series called Coronet Blue, which was a suspense series for CBS that was shot in New York. So I had a lot of New York background before I came to California. And I always kept an apartment in New York, and in later years I bought a brownstone in New York City. So I was a resident of New York, and I still have an apartment back there.

Well, I’d grown up in New York City and went to college at City College, which is located in Harlem. I always lived in New York, and then I came out to California after I’d had an extensive career in television — particularly in a lot television shows that originated in New York. First with live television, which originated usually at NBC or CBS in New York City. Then later on with shows like The Defenders, which were film shows that were filmed up in the uptown studios in New York City, and The Nurses, which was another show that was filmed in New York. Then I created a series called Coronet Blue, which was a suspense series for CBS that was shot in New York. So I had a lot of New York background before I came to California. And I always kept an apartment in New York, and in later years I bought a brownstone in New York City. So I was a resident of New York, and I still have an apartment back there.

In those days [while filming Black Caesar], Harlem was pretty run down. People were up against it. They’re hard luck people with poor opportunities for employment, poor opportunities for education. A lot of crime, praying mainly on their own people. Black people were robbing Black people. I mean, they would stray out of the Harlem area into the other areas of the city, but the majority of the victims were people in the neighborhoods, and it was a pretty sad state of affairs. And people did not take care of their property. People threw their garbage out the windows. People stole the light bulbs from the hallways of the buildings. I mean, it was just not a lot of care taken. And people would rent an apartment, and then move two or three families in with them, and have the place overcrowded with people — all of them sharing the rent.  Many people didn’t pay the rent, so there was constant evictions and things like that going on. It was not a place you would want to be, except to go to college there. I mean, you wouldn’t want to walk around in Harlem at night. That’s for sure. Not in those days.

Many people didn’t pay the rent, so there was constant evictions and things like that going on. It was not a place you would want to be, except to go to college there. I mean, you wouldn’t want to walk around in Harlem at night. That’s for sure. Not in those days.

One of the lead gangsters [in Black Caesar] told me, “Some day they’re gonna run all the Black people out of Harlem, and this real estate is gonna be worth a fortune.” That’s what he told me, but of course that’s 30-odd years ago. It took it a long time to happen, but it’s gradually happening. These buildings that existed before they became occupied as slums, many of them were very, very classy buildings. The neighborhoods were middle-class and upper-class White people, and they lived in Harlem, and that was around 1917. And my mother was born up in there, and my grandfather had a men’s furnishings store on  125th Street, which was a very fashionable street in those days. And then, gradually the area changed, and I guess a huge influx of Black people came from around the country seeking work and employment, and a new life in New York City. And they settled in Harlem, and once that happened, the White people moved out and more Black people moved in. And the houses that had once been so elegant with beautiful cornices, and beautiful sculptures, and marble, and beautiful tiles, and ornate staircases, all that stuff all went to hell. It was still there, but it looked terrible, because it hadn’t been sandblasted, it hadn’t been cleaned. People didn’t take good care of the buildings, and eventually they all fell into disrepair. And eventually, over the years, because of rent control in New York City, the landlords weren’t allowed to raise the rents commensurate with the expenses of oil and coal and salaries for superintendents. What happened was they weren’t making any money on the buildings,

125th Street, which was a very fashionable street in those days. And then, gradually the area changed, and I guess a huge influx of Black people came from around the country seeking work and employment, and a new life in New York City. And they settled in Harlem, and once that happened, the White people moved out and more Black people moved in. And the houses that had once been so elegant with beautiful cornices, and beautiful sculptures, and marble, and beautiful tiles, and ornate staircases, all that stuff all went to hell. It was still there, but it looked terrible, because it hadn’t been sandblasted, it hadn’t been cleaned. People didn’t take good care of the buildings, and eventually they all fell into disrepair. And eventually, over the years, because of rent control in New York City, the landlords weren’t allowed to raise the rents commensurate with the expenses of oil and coal and salaries for superintendents. What happened was they weren’t making any money on the buildings,  so they stopped paying the taxes, so they’d live off the money they’d originally paid in taxes, but they were now not paying taxes to the city. And the city didn’t want to foreclose the buildings, because they didn’t know what to do with them. And all these people living in these buildings, what are we gonna do with them? The few buildings they foreclosed were very soon shuttered, and the people were vacated and were put in hotels. They put them in these seedy hotels in mid-Manhattan, and they were paying hundreds of dollars a day for these people to be living in these hotels. And the hotels soon became squalid and ridden with garbage and rats. It was terrible, and the city was paying a fortune. Meantime, the buildings had been taken over as crack houses, and itinerants were living in these boarded-up buildings. They’d break in. So eventually, these buildings really went to total decay. And that was one of the low points in Harlem, when the landlords abandoned the property. You could have picked everything up for nothing in those days.

so they stopped paying the taxes, so they’d live off the money they’d originally paid in taxes, but they were now not paying taxes to the city. And the city didn’t want to foreclose the buildings, because they didn’t know what to do with them. And all these people living in these buildings, what are we gonna do with them? The few buildings they foreclosed were very soon shuttered, and the people were vacated and were put in hotels. They put them in these seedy hotels in mid-Manhattan, and they were paying hundreds of dollars a day for these people to be living in these hotels. And the hotels soon became squalid and ridden with garbage and rats. It was terrible, and the city was paying a fortune. Meantime, the buildings had been taken over as crack houses, and itinerants were living in these boarded-up buildings. They’d break in. So eventually, these buildings really went to total decay. And that was one of the low points in Harlem, when the landlords abandoned the property. You could have picked everything up for nothing in those days.

How did Black Caesar come about, and were there challenges in shooting on location in Harlem?

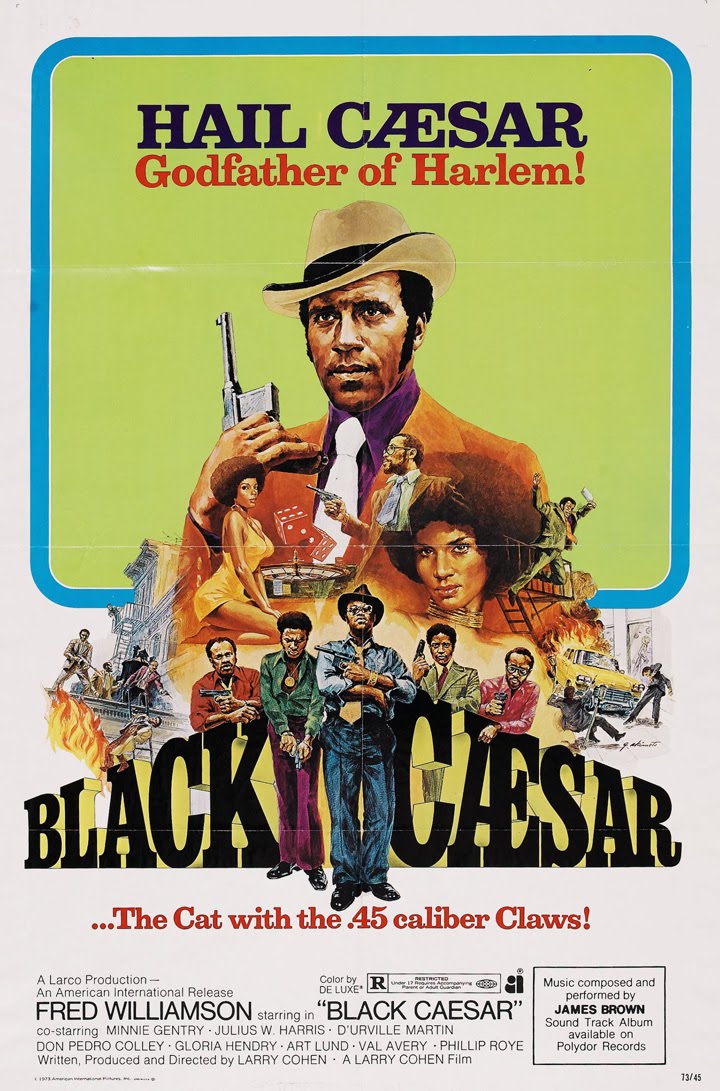

Black Caesar was originally commissioned by Sammy Davis Jr., who wanted to do a picture in which he was the star, instead of being a flunky to Frank Sinatra and Dean Martin. So I suggested that they do a gangster movie like Little Caesar, since he was a little guy, and so was Jimmy Cagney, and so was Edward G. Robinson. And I thought he could play a little hoodlum working his way up in the Harlem underworld. They liked the idea, so they commissioned me to write a treatment for $10,000. But when I finished writing the treatment, they did not give me the money. They said Sammy was in trouble with the Internal Revenue Service, and didn’t have $10,000 to give me. So I ended up with the treatment and no money. And then when I ran into Mr. Arkoff, who was the President of American International, he told me he was looking for an action movie that could star a Black actor. And I said, “Wait a minute,” and ran downstairs to the car and got the treatment, and came up with it, and we had a deal that afternoon. So, that’s how it came about. And then it was supposed to be Harlem, so obviously that’s New York, so we shot a great deal of the movie New York. Although we did shoot some interiors in Los Angeles.

Black Caesar was originally commissioned by Sammy Davis Jr., who wanted to do a picture in which he was the star, instead of being a flunky to Frank Sinatra and Dean Martin. So I suggested that they do a gangster movie like Little Caesar, since he was a little guy, and so was Jimmy Cagney, and so was Edward G. Robinson. And I thought he could play a little hoodlum working his way up in the Harlem underworld. They liked the idea, so they commissioned me to write a treatment for $10,000. But when I finished writing the treatment, they did not give me the money. They said Sammy was in trouble with the Internal Revenue Service, and didn’t have $10,000 to give me. So I ended up with the treatment and no money. And then when I ran into Mr. Arkoff, who was the President of American International, he told me he was looking for an action movie that could star a Black actor. And I said, “Wait a minute,” and ran downstairs to the car and got the treatment, and came up with it, and we had a deal that afternoon. So, that’s how it came about. And then it was supposed to be Harlem, so obviously that’s New York, so we shot a great deal of the movie New York. Although we did shoot some interiors in Los Angeles.

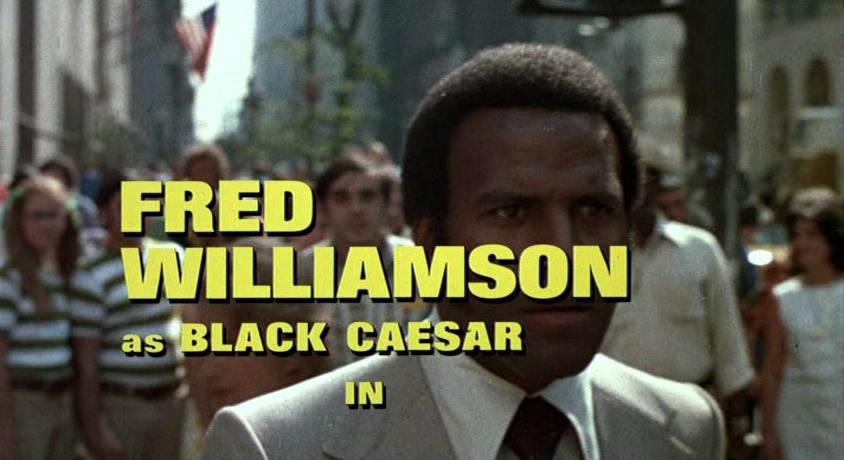

Fred loved the script and he loved the opportunity. He’d been in other films. He’d been a regular on the TV series Julia, and he had made some movies before, so he was a viable candidate for the part. He was a kind of a name actor for the black exploitation-type film. And that’s what they called these pictures at the time, although I think every movie is an exploitation film. You’re trying to sell your tickets to your audience, so every movie has that element of exploitation. You publicize it. You promote it. You try to get people to pay to come in and see it. So I don’t see what was any different about having a picture that would be geared to Black audiences. As a matter of fact, they had been denied the opportunity to see their people in heroic leading roles in movies, or anything glamorous or slick. Usually, they always had been pushed into the roles of servants or sidekicks. Or even as I said, Sammy Davis Jr. was playing a flunky. You know, in Ocean’s Eleven he was playing a garbage man. I mean, it’s disgraceful if you think about it.

Fred loved the script and he loved the opportunity. He’d been in other films. He’d been a regular on the TV series Julia, and he had made some movies before, so he was a viable candidate for the part. He was a kind of a name actor for the black exploitation-type film. And that’s what they called these pictures at the time, although I think every movie is an exploitation film. You’re trying to sell your tickets to your audience, so every movie has that element of exploitation. You publicize it. You promote it. You try to get people to pay to come in and see it. So I don’t see what was any different about having a picture that would be geared to Black audiences. As a matter of fact, they had been denied the opportunity to see their people in heroic leading roles in movies, or anything glamorous or slick. Usually, they always had been pushed into the roles of servants or sidekicks. Or even as I said, Sammy Davis Jr. was playing a flunky. You know, in Ocean’s Eleven he was playing a garbage man. I mean, it’s disgraceful if you think about it.

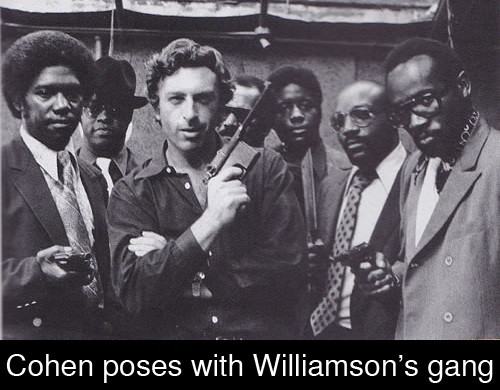

Fred was totally different than what Sammy would have played, because Fred was a handsome leading man. He looked great in the clothes, and he looked great in that hat that I put on him. And he could strut through Harlem, and he looked like the Godfather of Harlem. And when we went to shoot there originally, there had been another film shooting there called Across 110th Street, with Anthony Quinn. They had gone up to Harlem with all kinds of trucks, portable dressing rooms, portable toilets, and all kinds of equipment, and blocked up the streets and caused a lot of disruption. And they had been shaken down by the local gangsters in Harlem to pay them rather substantial fees in order to shoot on the different streets. So when I showed up with my small crew to shoot Black Caesar, we were immediately surrounded by these black gangsters who said,

Fred was totally different than what Sammy would have played, because Fred was a handsome leading man. He looked great in the clothes, and he looked great in that hat that I put on him. And he could strut through Harlem, and he looked like the Godfather of Harlem. And when we went to shoot there originally, there had been another film shooting there called Across 110th Street, with Anthony Quinn. They had gone up to Harlem with all kinds of trucks, portable dressing rooms, portable toilets, and all kinds of equipment, and blocked up the streets and caused a lot of disruption. And they had been shaken down by the local gangsters in Harlem to pay them rather substantial fees in order to shoot on the different streets. So when I showed up with my small crew to shoot Black Caesar, we were immediately surrounded by these black gangsters who said,  “You can’t shoot here unless you pay us.” And I didn’t have any money to pay them, so I looked at them and I said, “Hey, can you guys act? I think you guys would be great to play Fred Williamson’s gangster sidekicks, and I’ll put you all in the movie.” So the next thing you know, they’re all in the movie, and I was shooting any place in Harlem I felt like. And these guys were great. Anything we wanted, anything we needed to get, they got for me. We kind of owned Harlem after that. And then when the picture finally opened, I put them in the poster too, so that the advertisements in the paper had these guys in it. And opening day at the Cinerama Theater on Broadway, these gangsters were down there in front of the theater signing autographs.

“You can’t shoot here unless you pay us.” And I didn’t have any money to pay them, so I looked at them and I said, “Hey, can you guys act? I think you guys would be great to play Fred Williamson’s gangster sidekicks, and I’ll put you all in the movie.” So the next thing you know, they’re all in the movie, and I was shooting any place in Harlem I felt like. And these guys were great. Anything we wanted, anything we needed to get, they got for me. We kind of owned Harlem after that. And then when the picture finally opened, I put them in the poster too, so that the advertisements in the paper had these guys in it. And opening day at the Cinerama Theater on Broadway, these gangsters were down there in front of the theater signing autographs.

What led to your second collaboration with Fred Williamson on Hell Up in Harlem?

Black Caesar was a huge hit in New York City. It was big. It opened on Broadway, and it also opened on a bunch of other theaters. It opened on the east side, and it opened on 86th street uptown — originally on three first-run theaters, and then it graduated into opening on dozens of other theaters. I imagine at one time it must have played at 100 theaters in New York City at the same time, which was a big opening in those days. And White audiences came to see it too, but the initial rush to see the picture the first weekend was mainly a Black audience.

Black Caesar was a huge hit in New York City. It was big. It opened on Broadway, and it also opened on a bunch of other theaters. It opened on the east side, and it opened on 86th street uptown — originally on three first-run theaters, and then it graduated into opening on dozens of other theaters. I imagine at one time it must have played at 100 theaters in New York City at the same time, which was a big opening in those days. And White audiences came to see it too, but the initial rush to see the picture the first weekend was mainly a Black audience.

The picture did so well that they called me immediately and said, “You’d better get a sequel going before these actors decide they want an enormous amount of money to reappear.” So I said, “You know I don’t have a script, but I can start shooting something, and make it up as I go along.” That’s more or less what we did. We started almost immediately, and went back to Harlem. We still had our gangster friends up there, and they looked out for us, and got us the locations, and provided us with the protection we needed. The protection we needed wasn’t necessarily against gangsters. It was against teamsters and members of the unions that didn’t like non-union movies shooting in New York. And they would follow us up to the locations and try to stop the production. Except they wouldn’t follow us up to Harlem. When we got to 125th Street, the teamsters all turned back and left. They

The picture did so well that they called me immediately and said, “You’d better get a sequel going before these actors decide they want an enormous amount of money to reappear.” So I said, “You know I don’t have a script, but I can start shooting something, and make it up as I go along.” That’s more or less what we did. We started almost immediately, and went back to Harlem. We still had our gangster friends up there, and they looked out for us, and got us the locations, and provided us with the protection we needed. The protection we needed wasn’t necessarily against gangsters. It was against teamsters and members of the unions that didn’t like non-union movies shooting in New York. And they would follow us up to the locations and try to stop the production. Except they wouldn’t follow us up to Harlem. When we got to 125th Street, the teamsters all turned back and left. They  weren’t going to venture into Harlem, because they were mostly white guys, mostly Irishmen, and were not going to venture into that area that they felt unwelcome in.

weren’t going to venture into Harlem, because they were mostly white guys, mostly Irishmen, and were not going to venture into that area that they felt unwelcome in.

The second picture Fred was doing was That Man Bolt at Universal. He’d been hired to do this kind of a James Bond movie, and he was working five days a week at Universal. I was shooting another picture to called, It’s Alive for Warner Brothers. And I had a crew, and I said to Fred, “How about working for me on Saturday and Sunday?” So I had to get the crew to agree to work two extra days a week, so they ended up working a seven-day week working for me — five days a week on It’s Alive, and two days a week on Hell Up In Harlem. And we shot most  of Fred’s stuff out in California. Then I went to New York, and got a double to look like Fred from the back — although Fred thought the guy’s ass was too big, and he was complaining. Anyway, we shot most of the stuff in New York with the double, and then we came and shot the reverses back in California. I knew exactly what angles I needed, what shots I needed, what cuts I needed. So I had it all in my head, and I could do it. Probably no one else could have done it. But I was able to pull it off, because I writing the script as I was going along, and I knew exactly where I needed to put Fred in the scenes. So, we shot in Harlem. We shot in Harlem Hospital. We shot in a coal yard up in Harlem. We shot over there by the East River under a railroad bridge. We shot on 125th, and all around the

of Fred’s stuff out in California. Then I went to New York, and got a double to look like Fred from the back — although Fred thought the guy’s ass was too big, and he was complaining. Anyway, we shot most of the stuff in New York with the double, and then we came and shot the reverses back in California. I knew exactly what angles I needed, what shots I needed, what cuts I needed. So I had it all in my head, and I could do it. Probably no one else could have done it. But I was able to pull it off, because I writing the script as I was going along, and I knew exactly where I needed to put Fred in the scenes. So, we shot in Harlem. We shot in Harlem Hospital. We shot in a coal yard up in Harlem. We shot over there by the East River under a railroad bridge. We shot on 125th, and all around the  key places, and torn-down buildings, and wreckage of buildings. We went back to where we had shot the ending of the first picture, and picked it up from there with the double — and then we put Fred in. So it’s interesting to watch the picture to see where Fred is, and where the double is. To this day, Fred claims he was in scenes he wasn’t in. It even fooled him. But one of the kicks of the whole thing was to be able to finesse this thing so that you create something that was never really there. In the eyes of the audience, they see something that didn’t really exist, but you made it exist on film.

key places, and torn-down buildings, and wreckage of buildings. We went back to where we had shot the ending of the first picture, and picked it up from there with the double — and then we put Fred in. So it’s interesting to watch the picture to see where Fred is, and where the double is. To this day, Fred claims he was in scenes he wasn’t in. It even fooled him. But one of the kicks of the whole thing was to be able to finesse this thing so that you create something that was never really there. In the eyes of the audience, they see something that didn’t really exist, but you made it exist on film.

What led to your third collaboration with Williamson on Original Gangstas?

Years passed after we did Black Caesar and Hell Up In Harlem. I always stayed friendly with Fred. The pictures went into profits, so I was constantly sending him checks over the years for his share of the profits. So we got along fine, because I don’t think he ever got any profits from anybody else. People ordinarily don’t get profits from movies, but with this one he did very well. So as time went on, we remained cordial. Then I got a call from Fred out of the blue, saying he wanted to make a picture up in Gary, Indiana about a bunch ex-gang members who return to Gary and find themselves facing the new gangs that have sprung up, which are much more violent and deadly than his gang ever was when he was a kid. So he’d already had a script written on it, he had a screenplay, and he wanted me to direct the picture. So that was how it came about, and the reason why he picked Gary is because that’s the town where he grew up. He came from Gary, and his mother still lived in Gary. He was never able to get her to move out of there. She’d had her house there in Gary, and she’d lived there all her life, and she wasn’t about to move — even though the area was terrible. There was rampant unemployment. There wasn’t even a bank where you could cash a check. You had to go to a check-cashing store and pay an exorbitant fee. And everybody was locked behind glass, and to get into the place you’d have get through a buzzer system. I mean, there were so many burglaries and so many

Years passed after we did Black Caesar and Hell Up In Harlem. I always stayed friendly with Fred. The pictures went into profits, so I was constantly sending him checks over the years for his share of the profits. So we got along fine, because I don’t think he ever got any profits from anybody else. People ordinarily don’t get profits from movies, but with this one he did very well. So as time went on, we remained cordial. Then I got a call from Fred out of the blue, saying he wanted to make a picture up in Gary, Indiana about a bunch ex-gang members who return to Gary and find themselves facing the new gangs that have sprung up, which are much more violent and deadly than his gang ever was when he was a kid. So he’d already had a script written on it, he had a screenplay, and he wanted me to direct the picture. So that was how it came about, and the reason why he picked Gary is because that’s the town where he grew up. He came from Gary, and his mother still lived in Gary. He was never able to get her to move out of there. She’d had her house there in Gary, and she’d lived there all her life, and she wasn’t about to move — even though the area was terrible. There was rampant unemployment. There wasn’t even a bank where you could cash a check. You had to go to a check-cashing store and pay an exorbitant fee. And everybody was locked behind glass, and to get into the place you’d have get through a buzzer system. I mean, there were so many burglaries and so many  robberies. It was such a crime ridden area, and everything was ruled by gangs. The murder rate was probably the highest in the United States, and maybe it was the highest in the world at that time. That was before Mexico came in and claimed that title. There was a lot of violence down there, and when Fred told me he wanted to shoot the picture in Gary, I had my second thoughts about it. I said, “I don’t mind making a movie like this, but to shoot it in a gang capital — who knows who’s gonna get angry at you? You know, people can lose their temper very easily, and they have very violent reactions out there.” Well, we were gonna use real gang members in the picture playing members of the gang, use real gang people on the crew, and provide some employment for the people down there. So I said, “This is great, let’s go down and have a look at it.” So we went down and checked out Gary, and it was

robberies. It was such a crime ridden area, and everything was ruled by gangs. The murder rate was probably the highest in the United States, and maybe it was the highest in the world at that time. That was before Mexico came in and claimed that title. There was a lot of violence down there, and when Fred told me he wanted to shoot the picture in Gary, I had my second thoughts about it. I said, “I don’t mind making a movie like this, but to shoot it in a gang capital — who knows who’s gonna get angry at you? You know, people can lose their temper very easily, and they have very violent reactions out there.” Well, we were gonna use real gang members in the picture playing members of the gang, use real gang people on the crew, and provide some employment for the people down there. So I said, “This is great, let’s go down and have a look at it.” So we went down and checked out Gary, and it was  very run down and depressing. But it fit the movie, and Fred was adamant about shooting it there. So I said to him, “Look, I’ll do it.” But I really didn’t think he’d ever come up with the money to make the picture. I didn’t expect it would really happen. Many deals like this are proposed, and very few of them come true. But lo and behold, he showed up with the money, and said he had the funds to make the picture. And I couldn’t back out of it. I didn’t want him to lose the deal, so I just went ahead with it, and we went down there and shot the picture. Unfortunately, we got down there in the summer, and it was extremely hot. I mean, the average temperature was 100 degrees, so it was murder down there, and naturally everything was just desolate. There were a lot of burned-up buildings, and a lot of torn-down structures, and a lot of empty places. And Fred had gotten an entire city block which

very run down and depressing. But it fit the movie, and Fred was adamant about shooting it there. So I said to him, “Look, I’ll do it.” But I really didn’t think he’d ever come up with the money to make the picture. I didn’t expect it would really happen. Many deals like this are proposed, and very few of them come true. But lo and behold, he showed up with the money, and said he had the funds to make the picture. And I couldn’t back out of it. I didn’t want him to lose the deal, so I just went ahead with it, and we went down there and shot the picture. Unfortunately, we got down there in the summer, and it was extremely hot. I mean, the average temperature was 100 degrees, so it was murder down there, and naturally everything was just desolate. There were a lot of burned-up buildings, and a lot of torn-down structures, and a lot of empty places. And Fred had gotten an entire city block which  was abandoned, which had homes on it, and he had gotten permission to blow them all up. So they wanted to get rid of these places anyway, and they were empty, so what we did was we brought in a crew of people to paint them and put curtains in the windows and put little bicycles on the front lawn, and spruce the whole place up so the whole block looked like it was inhabited. And then one night, we just blew the whole place to smithereens. As a matter of fact, when that explosion went off, we were a couple of blocks away and I got a sunburn from the explosion. It was a much bigger explosion than we’d counted on, but it was great. It looked fabulous, and we blew up this whole block. And we had these kids, and they were gang members who came every day to work. They were always on time. They did everything they were asked to do. You know, if you wanted to shoot them and have them fall down,

was abandoned, which had homes on it, and he had gotten permission to blow them all up. So they wanted to get rid of these places anyway, and they were empty, so what we did was we brought in a crew of people to paint them and put curtains in the windows and put little bicycles on the front lawn, and spruce the whole place up so the whole block looked like it was inhabited. And then one night, we just blew the whole place to smithereens. As a matter of fact, when that explosion went off, we were a couple of blocks away and I got a sunburn from the explosion. It was a much bigger explosion than we’d counted on, but it was great. It looked fabulous, and we blew up this whole block. And we had these kids, and they were gang members who came every day to work. They were always on time. They did everything they were asked to do. You know, if you wanted to shoot them and have them fall down,  they did falls. They did anything you asked, and they were very friendly to me. They used to come to my trailer and bring me Famous Amos cookies, things like that. They did their best to ingratiate themselves. I was not concerned with the ones we hired, but with the ones that didn’t get hired. I thought, “Well, now one of the ones that didn’t get hired might just drive by one day with a machine gun or something, and polish us all off in one afternoon.” But it never happened. Everything was fine there for the entire shoot of the picture, and they were all very cooperative and pleasant. And then it was all over, and we left. And it was kind of sad, because while we were there they all had jobs, and they had some place to go every day, and they had some focus and some reason for being. Then when we left, we kind of just abandoned everybody. And there’s nothing we could do about it. We couldn’t take them back to Hollywood.

they did falls. They did anything you asked, and they were very friendly to me. They used to come to my trailer and bring me Famous Amos cookies, things like that. They did their best to ingratiate themselves. I was not concerned with the ones we hired, but with the ones that didn’t get hired. I thought, “Well, now one of the ones that didn’t get hired might just drive by one day with a machine gun or something, and polish us all off in one afternoon.” But it never happened. Everything was fine there for the entire shoot of the picture, and they were all very cooperative and pleasant. And then it was all over, and we left. And it was kind of sad, because while we were there they all had jobs, and they had some place to go every day, and they had some focus and some reason for being. Then when we left, we kind of just abandoned everybody. And there’s nothing we could do about it. We couldn’t take them back to Hollywood.  That’s where they lived, so there’s nothing we could do. Well, within two weeks after we left, the National Guard had to come in there. There was so much violence. They started killing each other right and left as soon as we were gone. So I felt there was a movie in that. A movie company goes to a gang town, and everything is great. And then they leave everybody behind, and this is what happens. You know, I felt bad about it, but there was really nothing I could do about it. You know, Gary isn’t that far from Chicago, and we have an apartment in Chicago. So I would go back to Chicago maybe on Sunday or something, the day we didn’t shoot. And then I’d come back to Gary, and then shoot the rest of the picture. And then when we left, we went back to Chicago, and that was it. We never went back to Gary again, and I haven’t been back there since. I’ve never heard from anybody in the town.

That’s where they lived, so there’s nothing we could do. Well, within two weeks after we left, the National Guard had to come in there. There was so much violence. They started killing each other right and left as soon as we were gone. So I felt there was a movie in that. A movie company goes to a gang town, and everything is great. And then they leave everybody behind, and this is what happens. You know, I felt bad about it, but there was really nothing I could do about it. You know, Gary isn’t that far from Chicago, and we have an apartment in Chicago. So I would go back to Chicago maybe on Sunday or something, the day we didn’t shoot. And then I’d come back to Gary, and then shoot the rest of the picture. And then when we left, we went back to Chicago, and that was it. We never went back to Gary again, and I haven’t been back there since. I’ve never heard from anybody in the town.

How successful was the theatrical release of Original Gangstas?

We opened the picture wide. It opened in a lot of theaters, and it didn’t do badly. Unfortunately, it opened the same day as Twister, and Twister had the biggest opening of the year. It was a very highly-publicized picture — tremendous amount of advertising. It must have been in 3000 theaters. And we were supposed to open a week before, but for some stupid reason Orion decided to postpone the opening and move it back a week. And Twister, which was supposed to open two weeks later, they moved their date up. So they ended up on the same day as us, and we were facing the most potent motion picture release of the year. So we were the second-highest grossing picture, and the second-highest theater average picture in the country. But that didn’t do us any good, because Twister just wiped everybody out. The picture got unusually good reviews, surprisingly, from the New York Times and from all the papers — really rave reviews. They likened it to Boyz n the Hood, and pictures like that. And they said it was a serious commentary on the conditions in Gary, Indiana and the people, and a worthwhile movie. And a New York critic said it was the most fun he’d had at the movies all year. So in a way it was a better picture than Twister, and I’m sure over the years it’s picked up most of its audience on DVD and cable.

We opened the picture wide. It opened in a lot of theaters, and it didn’t do badly. Unfortunately, it opened the same day as Twister, and Twister had the biggest opening of the year. It was a very highly-publicized picture — tremendous amount of advertising. It must have been in 3000 theaters. And we were supposed to open a week before, but for some stupid reason Orion decided to postpone the opening and move it back a week. And Twister, which was supposed to open two weeks later, they moved their date up. So they ended up on the same day as us, and we were facing the most potent motion picture release of the year. So we were the second-highest grossing picture, and the second-highest theater average picture in the country. But that didn’t do us any good, because Twister just wiped everybody out. The picture got unusually good reviews, surprisingly, from the New York Times and from all the papers — really rave reviews. They likened it to Boyz n the Hood, and pictures like that. And they said it was a serious commentary on the conditions in Gary, Indiana and the people, and a worthwhile movie. And a New York critic said it was the most fun he’d had at the movies all year. So in a way it was a better picture than Twister, and I’m sure over the years it’s picked up most of its audience on DVD and cable.