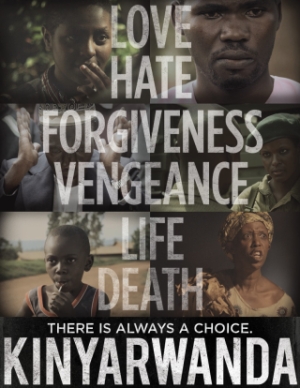

Who: Alrick Brown is an American filmmaker who wrote and directed 2011’s Kinyarwanda, which takes place during the 1994 Rwandan genocide — a 100-day period that claimed the lives of roughly 800,000 Rwandans. The film’s plot revolves around the decision by the country’s most influential Muslim leader, the Mufti of Rwanda, to issue a fatwa forbidding Muslims from participating in the killing of Rwandan Tutsis. The film takes accounts from several survivors who took refuge at the Grand Mosque of Kigali, and tells six interweaving narratives — including one involving the cooperative relationship between the mosque’s imam, a catholic priest, Tutsi refugees, and Hutus who refused to be participants in the genocide. Born in Jamaica and raised in Plainfield, New Jersey, Brown lived in Africa while serving 2 1/2 years as a Peace Corps volunteer in Cote d’Ivoire. He later returned to the continent to shoot Kinyarwanda on location in Rwanda — including some scenes in Kigali’s Grand Mosque. He attended a special screening of the film at Lincoln Center, presented by ImageNation Cinema Foundation and The Film Society of Lincoln Center. After the screening,

Who: Alrick Brown is an American filmmaker who wrote and directed 2011’s Kinyarwanda, which takes place during the 1994 Rwandan genocide — a 100-day period that claimed the lives of roughly 800,000 Rwandans. The film’s plot revolves around the decision by the country’s most influential Muslim leader, the Mufti of Rwanda, to issue a fatwa forbidding Muslims from participating in the killing of Rwandan Tutsis. The film takes accounts from several survivors who took refuge at the Grand Mosque of Kigali, and tells six interweaving narratives — including one involving the cooperative relationship between the mosque’s imam, a catholic priest, Tutsi refugees, and Hutus who refused to be participants in the genocide. Born in Jamaica and raised in Plainfield, New Jersey, Brown lived in Africa while serving 2 1/2 years as a Peace Corps volunteer in Cote d’Ivoire. He later returned to the continent to shoot Kinyarwanda on location in Rwanda — including some scenes in Kigali’s Grand Mosque. He attended a special screening of the film at Lincoln Center, presented by ImageNation Cinema Foundation and The Film Society of Lincoln Center. After the screening,  Brown took part in a discussion with Rwandan genocide survivor Marie Claudine Mukamabano, and Imam Talib Abdur-Rashid from New York City’s Mosque of Islamic Brotherhood. Camera In The Sun sat down with Brown to discuss Kinyarwanda ahead of the film’s theatrical release in seven U.S. cities on December 2nd, 2011 through the African-American Film Festival Releasing Movement. Theaters that screened the film include NYC’s AMC Empire 25, and Laemmle Music Hall in Los Angeles.

Brown took part in a discussion with Rwandan genocide survivor Marie Claudine Mukamabano, and Imam Talib Abdur-Rashid from New York City’s Mosque of Islamic Brotherhood. Camera In The Sun sat down with Brown to discuss Kinyarwanda ahead of the film’s theatrical release in seven U.S. cities on December 2nd, 2011 through the African-American Film Festival Releasing Movement. Theaters that screened the film include NYC’s AMC Empire 25, and Laemmle Music Hall in Los Angeles.

[Publisher’s Note: Special thanks to the staff at The Film Society of Lincoln Center, and at ImageNation]

What was the subject matter of your previous film work leading up to Kinyarwanda?

In film school, I used it as an opportunity to make several short films that are probably considered highly political, or charged. Because in film school, that’s where you can make those kinds of films without anyone telling you what to do. So my first short film [Familiar Fruit] was about lynching. The next one [The Adventures of Supernigger] was about police brutality. After that, I did one on domestic violence [Us: A Love Story], but tried to talk about the history of slavery using a Black and White interracial couple that had a rape at the beginning of their union — and now they’re living in this house together. So, I use that metaphor. All of my work had really intense subject matter, but I tried to do it in an entertaining way. I also produced a documentary in Guinea, West Africa [Death of Two Sons] about the life of Amadou Diallo — a West African immigrant who was shot 41 times by the police.

In film school, I used it as an opportunity to make several short films that are probably considered highly political, or charged. Because in film school, that’s where you can make those kinds of films without anyone telling you what to do. So my first short film [Familiar Fruit] was about lynching. The next one [The Adventures of Supernigger] was about police brutality. After that, I did one on domestic violence [Us: A Love Story], but tried to talk about the history of slavery using a Black and White interracial couple that had a rape at the beginning of their union — and now they’re living in this house together. So, I use that metaphor. All of my work had really intense subject matter, but I tried to do it in an entertaining way. I also produced a documentary in Guinea, West Africa [Death of Two Sons] about the life of Amadou Diallo — a West African immigrant who was shot 41 times by the police.

Alrick Brown: Director’s Reel from Alrick Brown on Vimeo.

What are your memories of hearing about the Rwandan genocide?

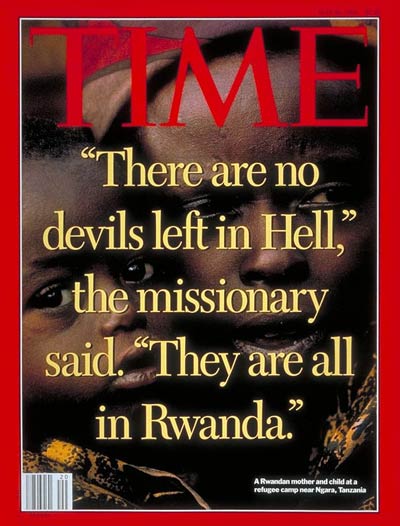

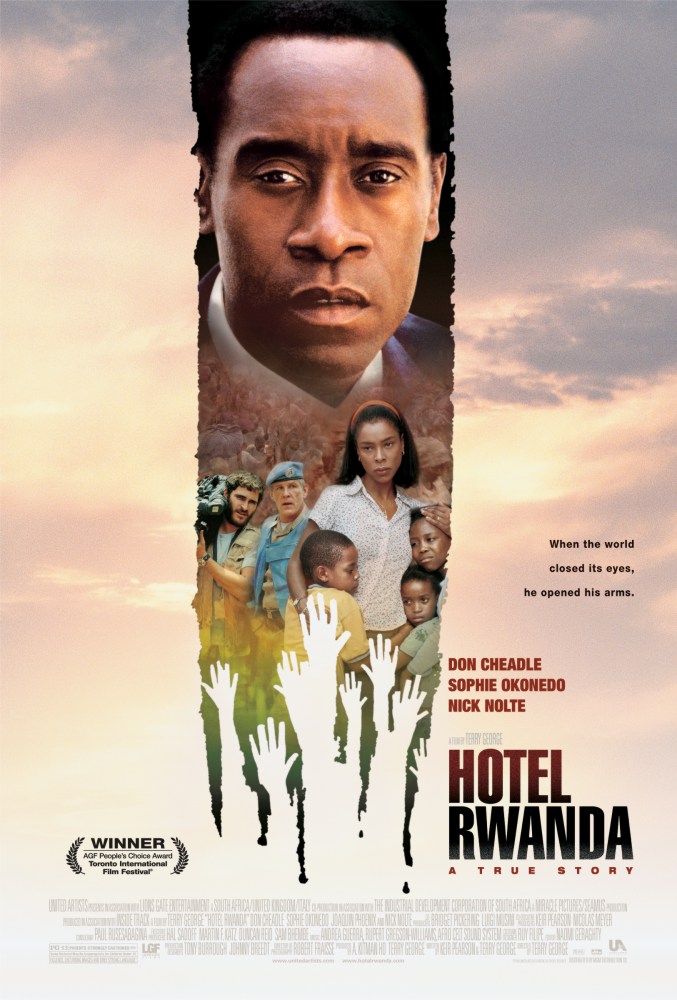

I’m 35 years old, and I’m angry because my memories of the Rwandan genocide were the few blips and bleeps and blurbs I heard on the news. I was a senior in high school. I think it wasn’t until a year later, I was in college and I came across a documentary on PBS that was talking about what happened. In this documentary, I’ll never forget this moment, there was a group of White embassy workers who were getting on a plane to leave. They were taking their dogs and stuff, and all of their Rwandan friends were saying, “Take us with you. Take us with you.” And they were crying, “We can’t take you with us.” So the Americans or Europeans got on the plane, and the documentary cut to a couple of months later when cameras went back in. And in the place they were standing, those same exact people were lying now on the ground, all chopped up. So people must have just been waiting for the Americans to leave. It wasn’t like they were waiting for a fight. They were just waiting for these people to leave, so they could do it. These people were killed right there. It stuck with me, and I was actually angry that this could happen and us not know about it. Later on, bigger Hollywood films like Hotel Rwanda, and then a film that I really appreciate and like, Sometimes in April came out. Then a really amazing documentary called Ghosts of Rwanda that PBS did. But it wasn’t until actually going to Rwanda that I actually got it for real. Those films gave you bits and pieces and different perspectives, but it was being in Rwanda and meeting the people that was kind of the genesis of this film, and how this all came about.

I’m 35 years old, and I’m angry because my memories of the Rwandan genocide were the few blips and bleeps and blurbs I heard on the news. I was a senior in high school. I think it wasn’t until a year later, I was in college and I came across a documentary on PBS that was talking about what happened. In this documentary, I’ll never forget this moment, there was a group of White embassy workers who were getting on a plane to leave. They were taking their dogs and stuff, and all of their Rwandan friends were saying, “Take us with you. Take us with you.” And they were crying, “We can’t take you with us.” So the Americans or Europeans got on the plane, and the documentary cut to a couple of months later when cameras went back in. And in the place they were standing, those same exact people were lying now on the ground, all chopped up. So people must have just been waiting for the Americans to leave. It wasn’t like they were waiting for a fight. They were just waiting for these people to leave, so they could do it. These people were killed right there. It stuck with me, and I was actually angry that this could happen and us not know about it. Later on, bigger Hollywood films like Hotel Rwanda, and then a film that I really appreciate and like, Sometimes in April came out. Then a really amazing documentary called Ghosts of Rwanda that PBS did. But it wasn’t until actually going to Rwanda that I actually got it for real. Those films gave you bits and pieces and different perspectives, but it was being in Rwanda and meeting the people that was kind of the genesis of this film, and how this all came about.

[Post-screening discussion] Brown on Hotel Rwanda, and how Rwandans view the film.

Hotel Rwanda is a brilliantly-acted film, and it’s a very important film. Without that story, many of us would still be very clueless about the horror of what happened in that country. It was a Hollywood version, but it hit us in the chest with the bodies. When I walked out of the theater, people asked me, “Did you like the movie?” I said, “It doesn’t matter. Go see it.” And that’s what happened on Netflix. For years, it was the #1 rented film, and it was important for people to see this film. The issue is that it wasn’t appreciated in Rwanda by many people. It wasn’t shown in Rwanda on a grand scale. They love Sometimes in April. They love that film, because it was a more accurate rendition. But the issue that Rwandans had — this is not me and my politics — when I got there, Ishmael and every other Rwandan kept telling me this issue of the gentleman portrayed in that film. The hero-izing of one man who essentially was profiting from the people who were coming in the hotel. And if they ran out of money, they were kicked out.

Hotel Rwanda is a brilliantly-acted film, and it’s a very important film. Without that story, many of us would still be very clueless about the horror of what happened in that country. It was a Hollywood version, but it hit us in the chest with the bodies. When I walked out of the theater, people asked me, “Did you like the movie?” I said, “It doesn’t matter. Go see it.” And that’s what happened on Netflix. For years, it was the #1 rented film, and it was important for people to see this film. The issue is that it wasn’t appreciated in Rwanda by many people. It wasn’t shown in Rwanda on a grand scale. They love Sometimes in April. They love that film, because it was a more accurate rendition. But the issue that Rwandans had — this is not me and my politics — when I got there, Ishmael and every other Rwandan kept telling me this issue of the gentleman portrayed in that film. The hero-izing of one man who essentially was profiting from the people who were coming in the hotel. And if they ran out of money, they were kicked out.  If they didn’t have any money, they couldn’t get in. And this is Rwandans telling that story. They wanted that line in the film. And I’m like “Really? Are you sure about this?” And our caterer, she’s a survivor, she stayed in that hotel. And she said, “Absolutely.” She was fortunate to have money. So the line ended up in the film. But in his defense though — because he’s not here, and can’t have a one-sided argument — he would argue that he still saved lives. And it’s very much like a Schindler’s List-type thing, if you look at Jewish history and what happened in Nazi Germany. So it’s complex, and that’s why you tell stories like this. I don’t want to hero-ize anybody. I don’t want to villain-ize anybody. I want to show the humanity and potential in all of us for good and evil. I think that Hotel Rwanda just kind of gave you good and bad. And you know, I think it’s a little bit grayer than that.

If they didn’t have any money, they couldn’t get in. And this is Rwandans telling that story. They wanted that line in the film. And I’m like “Really? Are you sure about this?” And our caterer, she’s a survivor, she stayed in that hotel. And she said, “Absolutely.” She was fortunate to have money. So the line ended up in the film. But in his defense though — because he’s not here, and can’t have a one-sided argument — he would argue that he still saved lives. And it’s very much like a Schindler’s List-type thing, if you look at Jewish history and what happened in Nazi Germany. So it’s complex, and that’s why you tell stories like this. I don’t want to hero-ize anybody. I don’t want to villain-ize anybody. I want to show the humanity and potential in all of us for good and evil. I think that Hotel Rwanda just kind of gave you good and bad. And you know, I think it’s a little bit grayer than that.

[Post-screening discussion] Brown on the depiction of Muslims and African culture in his film.

Rwanda is such an interesting country. People had a negative perception of Islam in Rwanda. They believed a lot of the stuff that they saw on the news. “Muslims are terrorists.” People were afraid of Muslims, and that’s one of the reasons why mosques were safe. I got there, and saw this community that was so integrated. Muslims and Christians get along. Christian kids go to Muslim schools, and vise versa. It’s not as segregated as we would have believed. In fact, a lot of my Muslim friends say they have to watch television to be reminded that they’re supposed to hate each other. Even a lot of Rwandans didn’t know how much influence the Mufti had. When the genocide broke out, he issued an edict, a fatwa forbidding Muslims from participating in the killing. And that’s what made mosques inadvertently the safest place, and Muslim communities the safest place. And at the time, the Muslim population was about 8%. And that’s gone up to 14-15%, because so many people were inspired. I’m not trying to romanticize it. There’s good and bad everywhere. And like one of our characters said, there were Muslims who still did participate. But in general it was the safest place in the country.

Rwanda is such an interesting country. People had a negative perception of Islam in Rwanda. They believed a lot of the stuff that they saw on the news. “Muslims are terrorists.” People were afraid of Muslims, and that’s one of the reasons why mosques were safe. I got there, and saw this community that was so integrated. Muslims and Christians get along. Christian kids go to Muslim schools, and vise versa. It’s not as segregated as we would have believed. In fact, a lot of my Muslim friends say they have to watch television to be reminded that they’re supposed to hate each other. Even a lot of Rwandans didn’t know how much influence the Mufti had. When the genocide broke out, he issued an edict, a fatwa forbidding Muslims from participating in the killing. And that’s what made mosques inadvertently the safest place, and Muslim communities the safest place. And at the time, the Muslim population was about 8%. And that’s gone up to 14-15%, because so many people were inspired. I’m not trying to romanticize it. There’s good and bad everywhere. And like one of our characters said, there were Muslims who still did participate. But in general it was the safest place in the country.

I just say thank you to [Imam Talib Abdur-Rashid]. This is really important because, for whatever reason, we haven’t had the Muslim community out supporting. We’ve reached out in many different levels, and we need that. I don’t know very many positive images of Muslims that we see in mainstream media. And it’s not revolutionary. It’s just the truth. To that effect, we didn’t show guns and violence and all that stuff, because we realized that you don’t necessarily change or end genocides with seas of faceless bodies. You know, we wanted to make one drop of blood precious, and one life precious. We wanted to show the humanity, the dancing. We wanted to show people. I think it’s offensive that in the other films that have come out, you don’t even get to know that they speak their own language, or you don’t get to know that they have a culture, and they have dreams.  In this country, when’s the last time you saw an African child dreaming, or sucking on a lollipop? We’re only supposed to see safaris and fat-bellied kids who are starving. That’s not the Africa that I lived in, or the Africa that I knew. So on many levels, things that I’m being applauded for as revolutionary are just things that are necessities in the images that we see. That’s why this release is important. That’s why working with AFFRM is important. That’s why having [Marie Claudine Mukamabano] here advocating for it is important. Because every filmmaker want’s the whole world to see their movie. I’m not that arrogant. I think there’s something for everyone to gain.

In this country, when’s the last time you saw an African child dreaming, or sucking on a lollipop? We’re only supposed to see safaris and fat-bellied kids who are starving. That’s not the Africa that I lived in, or the Africa that I knew. So on many levels, things that I’m being applauded for as revolutionary are just things that are necessities in the images that we see. That’s why this release is important. That’s why working with AFFRM is important. That’s why having [Marie Claudine Mukamabano] here advocating for it is important. Because every filmmaker want’s the whole world to see their movie. I’m not that arrogant. I think there’s something for everyone to gain.

What were the script-development and fund-raising processes like for Kinyarwanda?

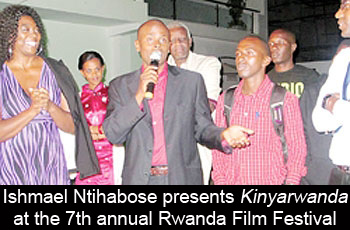

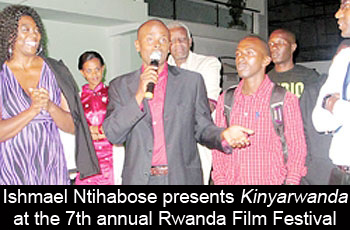

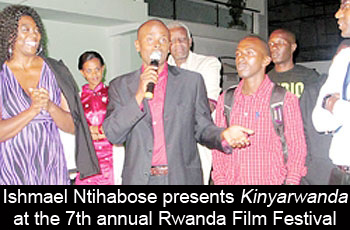

When I went to NYU film school, one of my buddies from Peace Corps ended up in Rwanda. He introduced me to the executive producer, Ishmael Ntihabose. Ishmael is a genocide survivor and aspiring filmmaker, who got a grant from a European commission to do a film about the genocide. His angle was a story that none of us knew. That’s why I say going to Rwanda was important. Very few Rwandans even know this, but during the genocide they had a religious leader in the country who made it forbidden for Muslims to participate in the killing. So, mosques inadvertently became some of the safest places in the country. Hutu and Tutsi and Christians and Muslims got together, and they were protected in the mosques. That’s the story he wanted to tell, about a priest and an imam. When I got to Rwanda, the budget was so small and we had so little time. I didn’t have time to take his story and write a full screenplay. I started meeting Ishmael’s family, friends and

When I went to NYU film school, one of my buddies from Peace Corps ended up in Rwanda. He introduced me to the executive producer, Ishmael Ntihabose. Ishmael is a genocide survivor and aspiring filmmaker, who got a grant from a European commission to do a film about the genocide. His angle was a story that none of us knew. That’s why I say going to Rwanda was important. Very few Rwandans even know this, but during the genocide they had a religious leader in the country who made it forbidden for Muslims to participate in the killing. So, mosques inadvertently became some of the safest places in the country. Hutu and Tutsi and Christians and Muslims got together, and they were protected in the mosques. That’s the story he wanted to tell, about a priest and an imam. When I got to Rwanda, the budget was so small and we had so little time. I didn’t have time to take his story and write a full screenplay. I started meeting Ishmael’s family, friends and  colleagues. They started telling me their own stories, and stories of other friends. Then I went to the genocide museum and saw stories. I said, “Ishmael, this is a film that should be about short stories, like Amores Perros, Pulp Fiction or Crash.” Because in a country where a million people are killed, everyone was effected in some way. Everyone has a story. So, that’s how the plot and the structure came about. I took a story of a child, a story of soldiers, a story of a couple going through their own marital problems, a couple of two teenage lovers — a Romeo and Juliet-type thing — then intertwined these stories to give you a more comprehensive look at life and love in Rwanda while the genocide was going on. The genocide is a backdrop to what otherwise is life. Because even in the most horrific situations, life still goes on. And the way I tie it up is that all of our characters end up meeting in Ishmael’s mosque.

colleagues. They started telling me their own stories, and stories of other friends. Then I went to the genocide museum and saw stories. I said, “Ishmael, this is a film that should be about short stories, like Amores Perros, Pulp Fiction or Crash.” Because in a country where a million people are killed, everyone was effected in some way. Everyone has a story. So, that’s how the plot and the structure came about. I took a story of a child, a story of soldiers, a story of a couple going through their own marital problems, a couple of two teenage lovers — a Romeo and Juliet-type thing — then intertwined these stories to give you a more comprehensive look at life and love in Rwanda while the genocide was going on. The genocide is a backdrop to what otherwise is life. Because even in the most horrific situations, life still goes on. And the way I tie it up is that all of our characters end up meeting in Ishmael’s mosque.

Ishmael applied for a grant, and he got it. I think we got about $300,000-plus dollars to do this film, but the money was in disbursements. So the initial budget was $250,000 to get it in the can. That was bigger than any budget I’d had previously, but smaller than most films. It was a lot of wrangling, a lot of favors, a lot of work went into pulling this off. Once we submitted a rough cut, we got additional funds. We also applied for grants from Cinereach, and we worked with IFP here in the United States. Our mission while in Rwanda was, “Get it in the can for $250,000.” That’s what we did, and we shot it in 16 days, and we were able to pull it off.

Ishmael applied for a grant, and he got it. I think we got about $300,000-plus dollars to do this film, but the money was in disbursements. So the initial budget was $250,000 to get it in the can. That was bigger than any budget I’d had previously, but smaller than most films. It was a lot of wrangling, a lot of favors, a lot of work went into pulling this off. Once we submitted a rough cut, we got additional funds. We also applied for grants from Cinereach, and we worked with IFP here in the United States. Our mission while in Rwanda was, “Get it in the can for $250,000.” That’s what we did, and we shot it in 16 days, and we were able to pull it off.

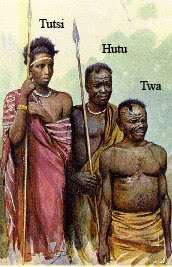

We filmed on location in Rwanda — in Kigali, the capital city. It’s a very peaceful and beautiful place. Rwandans are trying to practice moving beyond what happened.  They don’t use the terms Hutu and Tutsi anymore in common language. Me and my casting director, who’s an East African, came up with a code of how we could make sure that we were being historically accurate. But we never asked anyone what they were, or talked about it openly. That was never discussed on our set. We dealt with people as actors. It wasn’t a part of our process to identify and alienate, or anything like that. And I’m sure that there are scenes where we have some playing the others, just because they were better actors. Only Rwandans could see it and really know the difference. The labels at certain points in history got so arbitrary that it is kind of interesting, the different distinctions. But we didn’t focus on those distinctions.

They don’t use the terms Hutu and Tutsi anymore in common language. Me and my casting director, who’s an East African, came up with a code of how we could make sure that we were being historically accurate. But we never asked anyone what they were, or talked about it openly. That was never discussed on our set. We dealt with people as actors. It wasn’t a part of our process to identify and alienate, or anything like that. And I’m sure that there are scenes where we have some playing the others, just because they were better actors. Only Rwandans could see it and really know the difference. The labels at certain points in history got so arbitrary that it is kind of interesting, the different distinctions. But we didn’t focus on those distinctions.

Hutu and Tutsi were different cultures at one point, but they were intermarried, and got along perfectly fine, until the colonists came in and started kind of propping up one over the other. Resentment grew, and then there was this huge division that at certain points became arbitrary, because it was about who had more cows was one class. There are physical features that people say they can identify — usually more European features, like a pointy nose or lighter skin. People in power in the government used those distinctions, that were not a problem, to scapegoat. And from Armenia to Nazi Germany — I mean, you name it — it’s kind of the same game. Crips and the Bloods, the Shiites and Sunnis: it’s like, as long as they’re fighting, somebody else is in power and can control it. I’m sure you can find truth and roots in the [Rwandan] conflict. However, at the end of the day, same people, same land. They all want to live, and they all want to have their families. So it’s just a lot of propaganda. When I was living in West Africa, one of the big lessons that I learned really fast — because there’s only a few television stations if you don’t have satellite,

Hutu and Tutsi were different cultures at one point, but they were intermarried, and got along perfectly fine, until the colonists came in and started kind of propping up one over the other. Resentment grew, and then there was this huge division that at certain points became arbitrary, because it was about who had more cows was one class. There are physical features that people say they can identify — usually more European features, like a pointy nose or lighter skin. People in power in the government used those distinctions, that were not a problem, to scapegoat. And from Armenia to Nazi Germany — I mean, you name it — it’s kind of the same game. Crips and the Bloods, the Shiites and Sunnis: it’s like, as long as they’re fighting, somebody else is in power and can control it. I’m sure you can find truth and roots in the [Rwandan] conflict. However, at the end of the day, same people, same land. They all want to live, and they all want to have their families. So it’s just a lot of propaganda. When I was living in West Africa, one of the big lessons that I learned really fast — because there’s only a few television stations if you don’t have satellite,  and only like one or two newspapers — I saw how easy it is to manipulate people with the information that you send out. Because in the Ivory Coast, there’s like 60 ethnic groups, and everybody had something to say about the other ethnic group. It was just kind of funny. “Those people do this wrong. They do that wrong.” And it’s like, someone just changed the headline in the newspaper, and people’s minds start to shift. Rwanda’s no different. The genocide wasn’t just random killing that happened. No, it was a very calculated organized thoughtful thing that was decades in the making. You know, what happened in ’94 was like a blowup from things that had happened. There were several small genocides before ’94. It was just the first time we heard about this place and this conflict.

and only like one or two newspapers — I saw how easy it is to manipulate people with the information that you send out. Because in the Ivory Coast, there’s like 60 ethnic groups, and everybody had something to say about the other ethnic group. It was just kind of funny. “Those people do this wrong. They do that wrong.” And it’s like, someone just changed the headline in the newspaper, and people’s minds start to shift. Rwanda’s no different. The genocide wasn’t just random killing that happened. No, it was a very calculated organized thoughtful thing that was decades in the making. You know, what happened in ’94 was like a blowup from things that had happened. There were several small genocides before ’94. It was just the first time we heard about this place and this conflict.

Beyond doing away with the terms “Hutu” and “Tutsi”, what kind of healing is taking place?

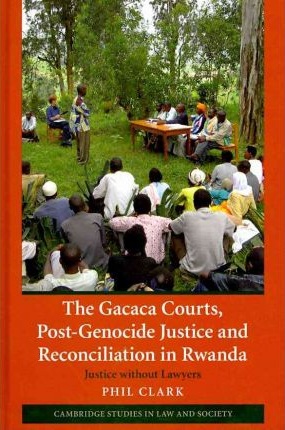

A part of the healing process in Rwanda was to talk about it, and have these Gacaca courts and reeducation camps, and truth and reconciliation — like things that were done in South Africa. So very much a part of their process of moving forward is to address what happened. I think enduring it would have been worse. Today it’s very much ingrained in a part of the culture, in the sense that whatever led to the genocide, they’re trying to do the exact opposite to make sure they never go back in that direction. So the songs that people sing now are songs of unity, and hope, and redemption, and forgiveness, and coming together, and brotherhood, and those type of things. So it’s ever-present. I think particularly the younger generation want to move on. They don’t want to dwell on the past, and don’t want to go back there. Even the idea of another movie about the genocide is off-putting to Rwandans. It’s a very interesting kind of psychology. Some cultures say, “Never forget.” In Africa, they kind of want to forget. But it’s so important that the story keeps getting told in different ways, because that’s how things change. I mean you put it in context, it’s only been 17 years since it happened, and it’s happening in other places right now. So the story still needs to be out there.

A part of the healing process in Rwanda was to talk about it, and have these Gacaca courts and reeducation camps, and truth and reconciliation — like things that were done in South Africa. So very much a part of their process of moving forward is to address what happened. I think enduring it would have been worse. Today it’s very much ingrained in a part of the culture, in the sense that whatever led to the genocide, they’re trying to do the exact opposite to make sure they never go back in that direction. So the songs that people sing now are songs of unity, and hope, and redemption, and forgiveness, and coming together, and brotherhood, and those type of things. So it’s ever-present. I think particularly the younger generation want to move on. They don’t want to dwell on the past, and don’t want to go back there. Even the idea of another movie about the genocide is off-putting to Rwandans. It’s a very interesting kind of psychology. Some cultures say, “Never forget.” In Africa, they kind of want to forget. But it’s so important that the story keeps getting told in different ways, because that’s how things change. I mean you put it in context, it’s only been 17 years since it happened, and it’s happening in other places right now. So the story still needs to be out there.

What was the local response to yet another American (you) making a film about the genocide?

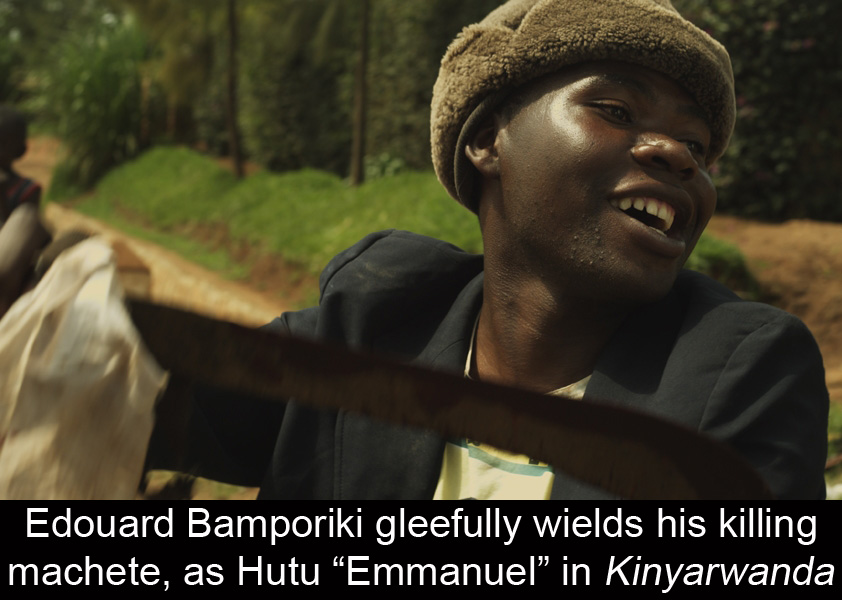

Since the genocide, one of the things that have come out is that a lot of people have gone to Rwanda to make films. I think a lot of Rwandans, seeing outsiders coming and telling their stories, have decided to pick up the camera and to write and to start telling their own stories. One of our lead actors, Edourd Bamporiki, he and his friends started a film company, because they worked on Lee Isaac Chung’s film Munyurangabo a couple of years ago. So they have created their own small infrastructure. That company is called Almond Tree, and they actually shot our behind-the-scenes video for Kinyarwanda. So we worked with them, and they have their own infrastructure. It’s not as big as ours, but they have stuff there. The Rwanda

Since the genocide, one of the things that have come out is that a lot of people have gone to Rwanda to make films. I think a lot of Rwandans, seeing outsiders coming and telling their stories, have decided to pick up the camera and to write and to start telling their own stories. One of our lead actors, Edourd Bamporiki, he and his friends started a film company, because they worked on Lee Isaac Chung’s film Munyurangabo a couple of years ago. So they have created their own small infrastructure. That company is called Almond Tree, and they actually shot our behind-the-scenes video for Kinyarwanda. So we worked with them, and they have their own infrastructure. It’s not as big as ours, but they have stuff there. The Rwanda  Cinema Centre has an educational program in film, and there’s about three or four educational schools, so they really embraced it. The crew, it was crazy, because we had some of the best people, and then we had some people who had never done it before. So it was kind of hard figuring out who had what skill. You can’t go by resume in a foreign country. It’s really tough to really know who’s who. It was a process of learning. But our casting director, our AC, our production designer — I mean, they were amazing. My first AD, who passed away recently, Steve Ntasi was a former-soldier with the RPF — the Rwandan Patriotic Front — during the war, who helped liberate the country. And so I made him an AD, just so he could be by my side and kind of run things. Most of our Rwandan crew had been assistants on other films, but in our film we made them head of their department. That was a part of what we wanted to do. And Simon Iyarwema did huge casting sessions, and brought us thousands of people — most of whom had never acted before, or who had sat as extras in other films and had just came out. And you know, we have about a thousand people in the movie. We had only two weeks to pre produce this whole thing, so I was looking for people who were committed, who were gonna show up,

Cinema Centre has an educational program in film, and there’s about three or four educational schools, so they really embraced it. The crew, it was crazy, because we had some of the best people, and then we had some people who had never done it before. So it was kind of hard figuring out who had what skill. You can’t go by resume in a foreign country. It’s really tough to really know who’s who. It was a process of learning. But our casting director, our AC, our production designer — I mean, they were amazing. My first AD, who passed away recently, Steve Ntasi was a former-soldier with the RPF — the Rwandan Patriotic Front — during the war, who helped liberate the country. And so I made him an AD, just so he could be by my side and kind of run things. Most of our Rwandan crew had been assistants on other films, but in our film we made them head of their department. That was a part of what we wanted to do. And Simon Iyarwema did huge casting sessions, and brought us thousands of people — most of whom had never acted before, or who had sat as extras in other films and had just came out. And you know, we have about a thousand people in the movie. We had only two weeks to pre produce this whole thing, so I was looking for people who were committed, who were gonna show up,  who had a particular look and particular age. Most of the people in the film are non-actors. A few of them, four or five, had acted in some previous films. Then to round out the cast, we brought in Cassandra Freeman from Spike Lee’s Inside Man, and Kena Onyenjekwe to play two soldiers. They played two characters whose families are exiled to Uganda, so they speak English. But it was mostly a non-professional acting team.

who had a particular look and particular age. Most of the people in the film are non-actors. A few of them, four or five, had acted in some previous films. Then to round out the cast, we brought in Cassandra Freeman from Spike Lee’s Inside Man, and Kena Onyenjekwe to play two soldiers. They played two characters whose families are exiled to Uganda, so they speak English. But it was mostly a non-professional acting team.

Kinyarwanda is the language that both the Hutus and Tutsis speak. It’s one of four languages spoken in Rwanda. They speak English, Kinyarwanda, French and Swahili. I saw the other films, and saw a lot of stuff about Rwanda, but I had no clue they spoke their own language until I arrived on the ground. It was bizarre. No one even mentioned that these people, these groups had the same language, and I thought it was a fascinatingly unifying thing. And since the film is based on these short stories, I thought the film should be called “Kinyarwanda,” because this is their voice, their language.

I had two Americans waiting back in the U.S. — Patricia Janvier, Charles Plath — to read every sentence, every scene. We only had time for one draft. There was no time to do anything more. Every time I wrote a scene, I sent it to them to proofread, to check if it was flowing, to see if it was working. And I worked with Ishmael for accuracy. I worked with Steve, who was a soldier, for accuracy in those things. Joshua, my Peace Corps buddy who’s living there now, is kind of a historian on Rwanda. Any time I found myself writing something I was unsure about, I vetted it through other people. Scenes that I thought were cool or fun, they’d say, “No, that doesn’t work. You wouldn’t do that in Rwanda.” I was extremely amenable to any of their realities. Again, I was a conduit. I was an advocate. I was listening. I was a good Peace Corps volunteer. I wasn’t going there to build a bridge. I was going there to see what they wanted to build. And I used those to create this story.

I had two Americans waiting back in the U.S. — Patricia Janvier, Charles Plath — to read every sentence, every scene. We only had time for one draft. There was no time to do anything more. Every time I wrote a scene, I sent it to them to proofread, to check if it was flowing, to see if it was working. And I worked with Ishmael for accuracy. I worked with Steve, who was a soldier, for accuracy in those things. Joshua, my Peace Corps buddy who’s living there now, is kind of a historian on Rwanda. Any time I found myself writing something I was unsure about, I vetted it through other people. Scenes that I thought were cool or fun, they’d say, “No, that doesn’t work. You wouldn’t do that in Rwanda.” I was extremely amenable to any of their realities. Again, I was a conduit. I was an advocate. I was listening. I was a good Peace Corps volunteer. I wasn’t going there to build a bridge. I was going there to see what they wanted to build. And I used those to create this story.

How much of your own life experience did you bring to telling that story?

I grew up in Jamaica. I was born in the ’70’s, and my family used to talk about the Manley and Seaga conflicts. Then I came and lived in New Jersey, and experienced racism from White people here, and self-hatred from Black people — African-Americans who hated me because I was too dark. Then I did Taekwondo, and was hated by Koreans. I just started to see that, “Oh, everybody has an issue.” My philosophy, as a young child always being the underdog, was “Why? Where does all this come from?” I just started to understand, “Why do African-Americans hate me? Why are White people afraid of me?” I started to ask the question, “Why?” and started to understand, as opposed to being angry or accept it. I don’t accept any of this stuff. I understand why a clansman is angry. I understand, and then I become a different type of storyteller. My mission in Kinyarwanda is the same thing. Going to Africa to listen not as an expert, but as an advocate. Hearing how people saw things and felt, I can write from a more humble place, and get some closer truths. I’m not making any heroes or villains, but showing the capacity in all of us for good and bad.

I grew up in Jamaica. I was born in the ’70’s, and my family used to talk about the Manley and Seaga conflicts. Then I came and lived in New Jersey, and experienced racism from White people here, and self-hatred from Black people — African-Americans who hated me because I was too dark. Then I did Taekwondo, and was hated by Koreans. I just started to see that, “Oh, everybody has an issue.” My philosophy, as a young child always being the underdog, was “Why? Where does all this come from?” I just started to understand, “Why do African-Americans hate me? Why are White people afraid of me?” I started to ask the question, “Why?” and started to understand, as opposed to being angry or accept it. I don’t accept any of this stuff. I understand why a clansman is angry. I understand, and then I become a different type of storyteller. My mission in Kinyarwanda is the same thing. Going to Africa to listen not as an expert, but as an advocate. Hearing how people saw things and felt, I can write from a more humble place, and get some closer truths. I’m not making any heroes or villains, but showing the capacity in all of us for good and bad.

What was the value of shooting on location, and did you try to use actual sites from the genocide?

The thing is, the entire country was ravaged by the genocide. There was not a place you could actually go to that was not affected. We shot in the mosque where our story actually took place. Just being in Rwanda, every location was a location. Every house, every home was a part of the story. So we tried to keep it as authentic as possible. But you know, Rwanda is a set.

The thing is, the entire country was ravaged by the genocide. There was not a place you could actually go to that was not affected. We shot in the mosque where our story actually took place. Just being in Rwanda, every location was a location. Every house, every home was a part of the story. So we tried to keep it as authentic as possible. But you know, Rwanda is a set.

I’ve only been shooting films on location for the most part, so I love it. But the truth is, a camera is a camera. And what’s captured in the camera, I don’t think it matters as much. The life in front of the lens is what matters. If you have to go someplace to recreate something, then as long as the life is truthful, you capture it. But you’ve got to be very careful, because people are from those places. They can see the lie immediately. So you’ve just got to convince the other millions of people out there. We’re storytellers, and sometimes we have limitations. The reason why we were able to shoot Kinyarwanda in 16 days is because we probably spent 8 of those days in one location. What’s that quote from that movie? “We use lies to tell truths.” And that’s what we did.

How was your film received by Rwandan audiences, and elsewhere?

The film screened in Rwanda at the Hillywood Film Festival. It’s their big festival in the summertime. I wasn’t there, but my co-producer Deatra L. Harris was. It was pretty magical. The Rwandans came out in huge support. It was an outdoor screening, and Rwanda is a very beautiful hilly place. Rwanda actually means “Land of a Thousand Hills.” And the screening was set up outside, with people sitting in balconies and rooftops just watching this thing. I heard people didn’t want to leave after it was over. It was the first film they felt really captured their personal stories, and gave them a holistic view. And it showed their culture and their language, and all these other aspects, and made them heroes. You know, Rwandans ended the war — Rwandans who were exiled. The RPF came back and helped end that war. They were abandoned by the Western powers. Our film touches on all of that, and so it was important to them, and we actually won the Rwandan Film Festival.

The film screened in Rwanda at the Hillywood Film Festival. It’s their big festival in the summertime. I wasn’t there, but my co-producer Deatra L. Harris was. It was pretty magical. The Rwandans came out in huge support. It was an outdoor screening, and Rwanda is a very beautiful hilly place. Rwanda actually means “Land of a Thousand Hills.” And the screening was set up outside, with people sitting in balconies and rooftops just watching this thing. I heard people didn’t want to leave after it was over. It was the first film they felt really captured their personal stories, and gave them a holistic view. And it showed their culture and their language, and all these other aspects, and made them heroes. You know, Rwandans ended the war — Rwandans who were exiled. The RPF came back and helped end that war. They were abandoned by the Western powers. Our film touches on all of that, and so it was important to them, and we actually won the Rwandan Film Festival.

We’re really proud. It premiered at Sundance, and it won the World Cinema Audience Award. It won the audience award at AFI, and we won at Skip City in Japan, which is crazy. The theatrical release on December 2nd is a really big thing. The point of this film is to get it out to the world, and to make sure many people see it. It does infuse something new in the dialogue. It’s a positive portrayal of Muslims, of Islam. It’s an interfaith film that shows religions coming together. It champions forgiveness, instead of vengeance as a policy of life and existence. It portrays Black skin and Black people in a way you don’t see very often. It’s multidimensional and has different shades of beauty. On many levels, artistically and politically, it does a lot of things. We want it to be seen by a lot of people. That’s the bonus. If it breaks box office records, it’s all the better for my career and for the people involved. Because I’ve been doing this a while, and people are afraid of me oftentimes, because they come to see me as political or always trying to have a message. And I don’t think there’s anything wrong with that. But the only way people with films that are meaningful can get ahead is if they do good numbers. And so, that will inspire other people. When I first got into this business, I remember someone saying to me,

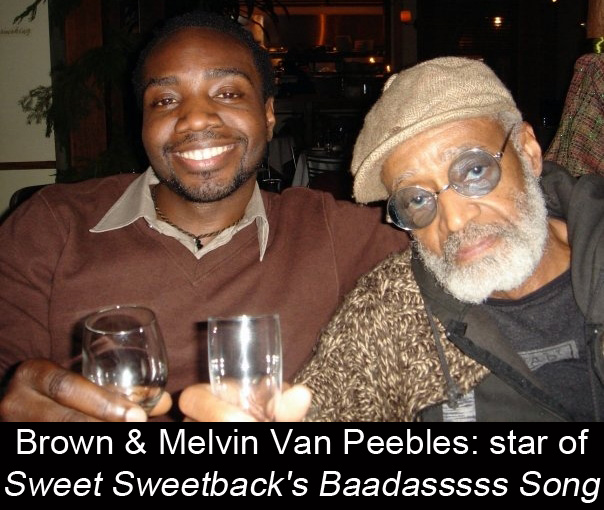

The theatrical release on December 2nd is a really big thing. The point of this film is to get it out to the world, and to make sure many people see it. It does infuse something new in the dialogue. It’s a positive portrayal of Muslims, of Islam. It’s an interfaith film that shows religions coming together. It champions forgiveness, instead of vengeance as a policy of life and existence. It portrays Black skin and Black people in a way you don’t see very often. It’s multidimensional and has different shades of beauty. On many levels, artistically and politically, it does a lot of things. We want it to be seen by a lot of people. That’s the bonus. If it breaks box office records, it’s all the better for my career and for the people involved. Because I’ve been doing this a while, and people are afraid of me oftentimes, because they come to see me as political or always trying to have a message. And I don’t think there’s anything wrong with that. But the only way people with films that are meaningful can get ahead is if they do good numbers. And so, that will inspire other people. When I first got into this business, I remember someone saying to me,  “Don’t make movies about Black people.” It was a Black woman. She was trying to give me advice. She was working at a big television station at the time. And I looked at her, and nodded my head thinking, “You’re screwed up. You don’t even know it.” It makes perfect sense, and people will stand by that, because it’s such a difficult thing to tell those type of stories, and get funding for those stories. But that doesn’t mean the system is right. There’s tons of films, good and bad, that kind of need to be made — revolutionary ones. Spike Lee’s Do the Right Thing, and also Melvin Van Peebles’ film Sweet Sweetback’s Baadasssss Song. Those films had to be made. But you have Eve’s Bayou, Daughters of the Dust and Haile Gerima’s Sankofa. There’s all these films that show different things. But there’s a reason why AFFRM, and ImageNation, and organizations like that are important. It’s because oftentimes African-Americans and mainstream audiences don’t get to some of those works. They don’t see some of those projects.

“Don’t make movies about Black people.” It was a Black woman. She was trying to give me advice. She was working at a big television station at the time. And I looked at her, and nodded my head thinking, “You’re screwed up. You don’t even know it.” It makes perfect sense, and people will stand by that, because it’s such a difficult thing to tell those type of stories, and get funding for those stories. But that doesn’t mean the system is right. There’s tons of films, good and bad, that kind of need to be made — revolutionary ones. Spike Lee’s Do the Right Thing, and also Melvin Van Peebles’ film Sweet Sweetback’s Baadasssss Song. Those films had to be made. But you have Eve’s Bayou, Daughters of the Dust and Haile Gerima’s Sankofa. There’s all these films that show different things. But there’s a reason why AFFRM, and ImageNation, and organizations like that are important. It’s because oftentimes African-Americans and mainstream audiences don’t get to some of those works. They don’t see some of those projects.