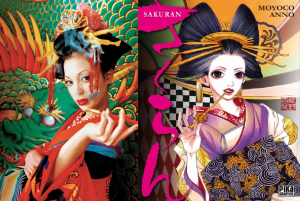

Sakuran is a stunningly colorful film by director Ninagawa Mika based on a serialized manga, a Japanese comic, of the same name. The movie depicts the life of a young woman by the name of Kiyoha, from the time of her sale into a kamuro house, a Japanese brothel, to her ascension to oiran, the head kamuro in her house. Upon its release in 2006, the movie generated a surcprising amount of controversy, both in Japan and in the west, for a number of reasons; what’s most strange, however, is the discrepancy between subject of domestic versus international criticisms, and the way each reflected the culture from which it came.

Oiran in the 19th century

Oiran were known as “pleasure givers” during the Edo period of Japan (1603-1868) who catered to the highest calibre customers: samurai, nobility, and the like. These women were more than just prostitutes though; they were also entertainers, and were expected to be well-versed in any of a variety of traditional Japanese arts including singing, dancing, playing instruments, tea ceremony, and ikebana, Japanese flower arrangement. (It is the oiran who gave birth to kabuki theater and were the predecessors of the later geisha who served only as entertainers in traditional arts without offering sexual favors.) Oiran were also expected to be intelligent and interesting enough to converse with the nobility they entertained.

Kiyoha, the oiran in Sakuran, played by Anna Tsuchiya, is not particularly well educated nor is she exceptionally good at any of her studied arts, but she has a fire tongue and liquid eyes that capture the attention of men, and a hot temper that sets her away and apart from the other kamuro in her house, and this is what eventually earns her a promotion to oiran.

Unlike the other girls who act genteel, giggle entrancingly, and offer sweet agreements to everything their customers say, Kiyoha gives her opinion on political matters, thinks nothing of disagreeing with anyone and anything, and blatantly stands up her most expensive customers to flirt with the young ones whom she portends to love. Her opinions surprise the men, and her refusal to meet with them is played off as an extreme form of her coquettish shyness.

American viewers tend to approve of Kiyoha’s behavior, but they dislike Tsuchiya, seeing her acting as substandard to the outspoken, bold women that have featured so prominently in western movies for the last several decades. They often do point out, however, that she acts with the muted, gentle anger that they would expect from a Japanese woman. Kiyoha is certainly angry at being sold into prostitution – but not as angry as we might expect. She is ultimately dissatisfied with her life because she is not allowed to seriously fall in love, and not because she has been forced to sell her body. But Japanese reviewers also tend to dislike her, though for a different reason: she does not uphold the untouchable grace and elegance that an oiran is supposed to have. Part of this is because they feel her dialogue is overdone and cheesy, and too modern in comparison with the other characters, which is lost in the translation to English, but a good portion of this comes from her acting skills, and her character’s persona, as one who complains, who stands out, who shows dissatisfaction.

They claim her villainy is too strong; the previous oiran, they claim, was also strong, bold, powerful, but without the bite of evil that made her so dislikable. In other words, western viewers think she is not bold enough, that her individuality is unpracticed and unconvincing; Japanese viewers think she is too bold, and not in line with Japanese ideals. Each culture aligns her with themselves, then rejects her soundly.

This dichotomy continues with the other characters in the movie as well. The kamuro and various oiran are all sex workers, and yet none of them really seem to suffer; in one scene in particular, the kamuro are all gathered together discussing a high level samurai’s courtship of Kiyoha, and they, the lesser ranked kamuro, giggle at the fact that they’ll never amount to anything themselves. Moreover, they don’t seem to be put off by what westerners would consider the indignity of their jobs. They squeal with pleasure at the sight of their favorite customers and bemoan their less favorites with only the vitriol of anyone who has ever worked in customer service. Thus, while large parts of the movie are shockingly realistic in addressing prostitution (the gaudy scenery, the side effects of prostitution that include STDs, abortion, and violence, and the women’s lack of control over their situation), it is the characters themselves who seem the most unrealistic.

Kiyoha alone seems upset with her situation and her lot in life, but still not proportionately so. Nonetheless, it is the westerners who are upset by their passive acceptance; the Japanese audiences worry they are not passive enough for their time period, for their duties.

Furthermore, this dual reaction was present in almost every aspect of the movie; even the music, a modern soundtrack to go with a period film sparked difference in opinion: the westerners mostly seemed to dislike it, feeling it out of place, while the Japanese saw it as an extension of the modernism of the manga and in line with the historical discrepancies they saw rife in the movie (discrepancies mostly missed by westerners). Furthermore, pop music is overwhelmingly omnipresent in Japan, as most of southeast Asia is currently within the throws of a boy band mania that is strangely not limited to the youth. Bubbly pop music is combined with every art form and every part of life, and so seems at home in this historically inaccurate drama with its noticeably modern feel (reviewers have even pointed out that Anna Tsuchiya is half Polish, half Japanese, a mix which would have been unconscionable during the Edo period, and which distinguishes the movie as made in a more modern time). Again, the westerners fell on one side, disliking the soundtrack, while the Japanese tended to find it bubbly, interesting and, maybe a bit too good for the film.

One thing viewers from both cultures agree on, however, is that the movie is beautiful to watch. It is depicted almost entirely in shades of oranges and reds, giving it a truly visceral feel throughout. Goldfish are a recurring theme, being kept as a sign of wealth and luxury, and imprisoned beauty, and their deep orange hues set an early tone for the movie. Sakura, the cherry blossoms from which the movie gets its name, are another recurring motif and their pale pink petals are often set as the only colors in otherwise dark scenes. Most scenes are set up and designed as beautifully as photographs and indeed the director, Ninagawa Mika, is better known for her overly vibrant yet beautiful photography.

At the same time, parts of the movie take on an almost gaudy look, looking garish and too bright, a bit like early Technicolor movies. In fact, these scenes are probably the most realistic; gaudy colors are typical of some of the most well known parts of modern Japan, and typical of the more visible parts of the modern sex industry, in particular love hotels, which are so garish as to often be built like castles, with shining mirrors and red satin galore. But these garish, bright scenes, in addition, often seem overly staged and posed, though there is a particular reason for this: having been adapted from a manga, many of the scenes are specifically created images meant to look like manga. The movie is visually fairly faithful to the spirit of the original story, so much so that parts of it seem to be lifted right off of the pages, though the plot differs in several major points. Poses are struck, scenes are carefully arranged, backgrounds are shown in reliefs that seem as though they’ve been made real from drawings.

This adherence to a visual focus is beautiful and striking, but it has the effect of making much of the movie seem overly staged and unnatural. American reviewers criticized this as being too beautiful for a whorehouse, picturing, of course, the western views of brothels as dirty, dark places, resplendent with only dirt and decay. Japanese critics suggested the decorations looked too cheap for someone as high in rank as an oiran.

One striking part of the movie is the meandering feel of the plot. The plot has less of a traditional story arc than westerners are usually used to from films that come out of Hollywood, instead taking on a slice-of-life feel, if anyone’s average slice-of-life could be living and entertaining in a kamuro house. The movie is bookended well with Kiyoha’s entry into and exit from the brothel, though the events in between don’t seem to build up toward resolution so much as show the shaping of a woman. This particular characteristic comes less from a penchant for true-life stories than it does from the mode of its creation: like so many Japanese movies, it started out serialized in manga form, appearing as a series of episodes in a magazine, which were later compiled into one large volume. As a result, events in the story seem to take on an independent quality; they’re more or less unrelated to each other, and several of the seemingly crucial points get more or less forgotten or rendered unimportant a mere ten or fifteen minutes later. The tag line claims the movie is the story of love in an improbable place, but love is not a driving plot element, so much as it is tangential to the story of Kiyoha’s life.

Perhaps the most surprising visual aspect of the movie is that it is almost shockingly pornographic in some parts, most notably when the young Kiyoha first enters the kamuro house. Her first communal bath in the house leaves an impression only of a swirling mass of bouncing breasts in the steam represented by a full minute long montage of them, while her one early act of rebellion leads her to peek into a room unbidden where she sees the current oiran naked, riding a customer, and realizes this to be her future. (For all these vivid depictions, however, genitalia of either gender are never shown; despite the proliferation and accessibility of pornography in Japan, the country has strong taboos against showing genitalia, and many magazines and movies self-censor, often with blurring. For art’s sake, Sakuran avoids these shots altogether, both in the manga and the movie.) Naked couples in the midst of pleasure are a frequent sight in the movie. This is perhaps realistic to a large extent: the Japanese are somewhat more comfortable with nudity in their daily lives than westerners and, moreover, nudity seems rather expected in a prostitution house. The fact of the nudity is not the shocking part; rather, it is the cavalier presentation of said nudity. In western movies, nudity is still special; it usually occurs only in emotionally charged scenes, and it is shown purposefully and carefully. In contrast, the nudity in Sakuran is almost casual. The kamuro bathe and no effort is made to hide their nudity. Young Kiyoha opens a door and sees the current oiran on a man, and she does not hide her skin, nor is it crudely hidden by some object in the foreground.

Adult Kiyoha happens upon other kamuro in the midst of their business and they are no more covered than reality would expect. While Kiyoha may, at first, shy away from this abrupt nudity, the film does not. To a western audience, this is surprising if nothing else, but to a Japanese audience, this kind of nudity is expected from these kinds of women, and is perhaps less startling. It seems, in fact, more routine than nudity usually does in movies; more natural and more organic as a product of the situation. Because it is considered more acceptable, and more normal, especially for the period of the film, the scenes of nudity do not come off as the focus or the climax of the movie, but rather as tangential to the building of the character; scenes that are more significant to her life than the movie. This sort of nonchalance about events is exactly what gives the movie its slice-of-life feel, rather than following a traditional movie arc.

Early on in the movie, Kiyoha appears to fall in love (though her performance is a little unconvincing), but her lover seems to disappear without pomp or reaction later in the movie. Further on in the movie, she becomes pregnant from one of her customers and vows to keep the child in what initially seems like a turning point in her character, but when she loses it later on, there appears to have been almost no character shift. Events happen and end, and nothing in Kiyoha’s situation seems to change or evolve.

For a Japanese audience, this is somewhat normal; many shows and movies in Japan start out as manga as this one did, and thus retain an episodic feel from their parent form. All the same, the disconnect led to both Japanese and western reviewers calling the movie dull.

Kiyoha, as an under-defined character (as seen from both perspectives) sometimes bores the viewer with her indecipherable twists of will, and the lack of a single plot thread leaves the movie somewhat anti-climactic.

For all the criticism, however, westerners tended to rate the movie higher than Japanese people did. Some of the negative reviews on the part of the Japanese came from the fact that the Japanese reviewers had often read the manga before seeing the movie and were disappointed by the comparison. The westerners tended to be more dazzled by the colors than anything else and, while disliking many parts of the movie, found this aspect to be so undoubtedly redeeming that it left an indelible impression.