It starts off simply enough: an establishing shot over Juneau, Alaska gives way to a panoramic view of Stewart, British Columbia (the director’s stand-in for the South Pole circa-1982). Amidst a heavy bassy monotone soundtrack, a helicopter is seen chasing an Alaskan Malamute across the “Antarctic” plains. There’s a man, a sniper, hanging over the side. He’s firing frantically at the dog. This chase will end fatally for the Norwegians at United States Science Institute Station 4 — later referred to (mistakenly) by Kurt Russell’s character as “Outpost 31″ — as miscommunication and panic leads to the death of the two men who tried, in vain, to kill a harmless-seeming animal. What, if anything, does this have to do with the flying saucer we see during the film’s foreboding framing sequence? We, and the American researchers at USSIS 4/”Outpost 31,” will spend the next 90 minutes learning just that…

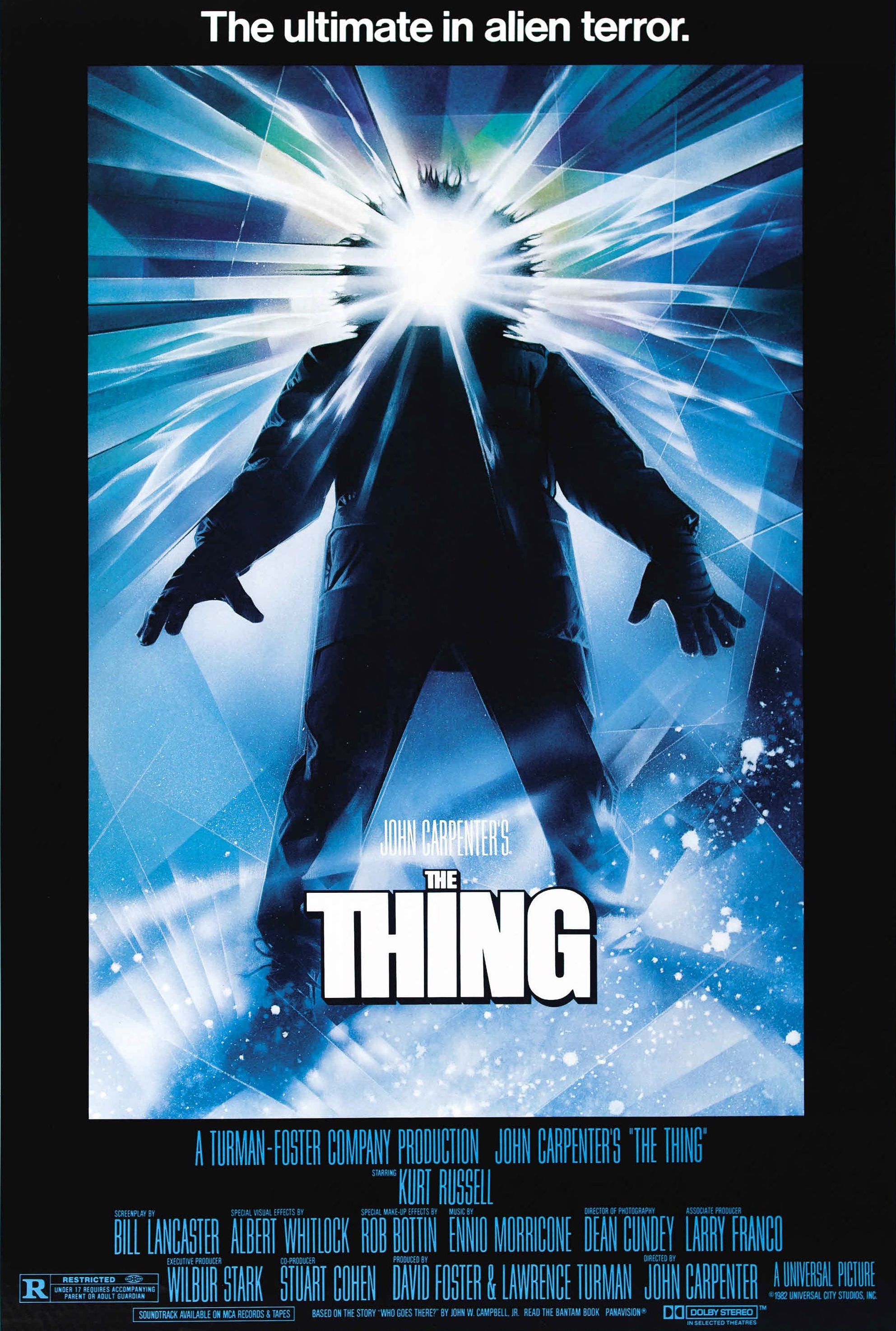

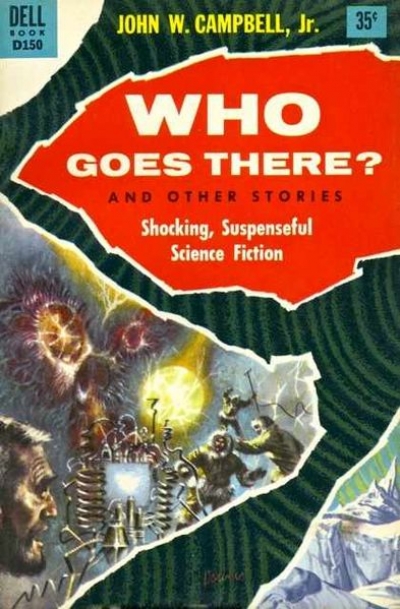

John Carpenter’s The Thing is a remake of The Thing from Another World (1951) — which itself is an adaptation of John W. Campbell’s masterful novella Who Goes There? (1938) . The Thing is also considered by many (this writer included) as the best sci-fi horror movie — if not the best horror movie, period, ever filmed. It’s also the first of three thematically-related films Carpenter refers to as his “Apocalypse Trilogy.” They comprise of this film, Prince of Darkness and, finally, In the Mouth of Madness.

. The Thing is also considered by many (this writer included) as the best sci-fi horror movie — if not the best horror movie, period, ever filmed. It’s also the first of three thematically-related films Carpenter refers to as his “Apocalypse Trilogy.” They comprise of this film, Prince of Darkness and, finally, In the Mouth of Madness.

The Thing was arguably the most subtle of these “Apocalypse” films, perhaps owing to its source material (an adaptation of an adaptation of a book written in 1938), and the location of the story itself. While the latter two films in Carpenter’s thematic trilogy take place in Los Angeles and the fictional town of Hobb’s End, New Hampshire respectively — the titular Thing sows its terror in utter isolation, in the dead of winter on the coldest continent at the end of the world. Indeed, only a few fleeting sequences within the film suggest that the creature’s threat is global in scale. And even those dire warnings are liable to fall on deaf ears, as the audience hears them from a rather unreliable source — the increasingly unhinged Dr. Blair, played charmingly (amusingly?) enough by Wilford “Diabeetus” Brimley. Meanwhile, the viewers, as well as the characters themselves, are instead subjected to less-subtle threats in the form of the alien’s grotesque means of procreation/consumption.

If there was an official rulebook on crafting the “perfect” horror film, this movie could arguably serve as the standard. Certainly it has its flaws (questionable cast choices in particular, and just what were those researchers researching anyway?). But between its masterful blend of fear of the unknown (an unknown evil… froooom spaaaace!!!), fear of isolation (Antarctica), fear of abandonment (during the winter), fear of betrayal (shapeshifter in our midst), all our primal anxieties are masterfully interwoven into the framework of John Carpenter’s sci-fi horror masterpiece. The alien thing preys on its human victims just as winter descends on “Outpost 31”, and leaves the researchers stranded for a season, alone against a threat that can take their very shapes — and sets a group who should be banding together at each-others throats.  The very conceits that we take for granted as human beings, be they subliminal or otherwise, as social animals, as predators, are completely uprooted by this “Thing” which can steal our shapes and turn us — “the pack” — against one another, even as it devours us one-by-one and spreads like the ultimate virus.

The very conceits that we take for granted as human beings, be they subliminal or otherwise, as social animals, as predators, are completely uprooted by this “Thing” which can steal our shapes and turn us — “the pack” — against one another, even as it devours us one-by-one and spreads like the ultimate virus.

Despite it’s scenic locale, most of the film was shot indoors on several sound stages at Universal Studios, right in the heart of sunny California -in the middle of the summer, no less. That didn’t stop the director from traveling to Steward, British Columbia (specifically, Salmon Glacier) to build a mock up of the American/Norwegian “camps” (actually one and the same… the “Norwegian Camp” is actually just the American outpost after they blow it up at the end of the film. The camp was built specifically for the film and no longer exists, sadly, although remains of it were found around Salmon Glacier as late as 2003). Nor did they spare any expense sending a 2nd unit crew over Juneau, Alaska to set up establishing shots — as well as the shots of the Norwegian researchers discovering the alien ship.

As for Universal Studios’ Stage 27 itself, Carpenter and crew made sure to keep the environs at-or-near freezing temperatures at all times. This doubtless had the (desired?) side-effect of causing the cast to become that much more miserable and anxious on set — anxieties which bled into their performances (Kurt Russell and Keith David’s in particular, I think).

The last weeks of shooting — primarily the exterior shots of the camp — were actually done in November and December of that year at Steward, so that artificial freezing was no longer necessary. They chose a location near the Alaskan border during the late autumn/early winter months. Snow and ice — and isolation — were virtually guaranteed, and granted those exterior scenes an added layer of hopelessness. No one was coming for them. No one would ever know what happened or why. And that was the optimistic outcome. The worst-case scenario saw the alien surviving, going into hibernation, and waking up to infiltrate the rescue teams — only to spread outwards from there, eventually consuming the whole planet.

The ending of the film itself is suitably nihilistic. While the final scene can be interpreted in several ways, none of the likely scenarios seem kind or even fair to the remaining survivors — one of whom might in fact be the alien in disguise, merely waiting for the other to drop his guard. And so the film ends as it began, with that foreboding brassy monotone, a shot of the title card (much more subdued this time), and an ending which is neither happy, nor complete, but leaves the viewer riven with anxiety. That is, assuming said-viewer cares enough about the characters at this point to worry about their fates. Indeed, depending on how one takes the film, the viewer is likely to be just as resigned to the characters’ fates as the characters themselves on screen — which in itself is horrific enough.

Upon its release, the film suffered from lackluster reviews, owing mostly to the graphic nature of the alien and the necessarily-gory special effects required to communicate its various forms. But the film has since gained a strong cult following, which has spawned a video game sequel, comic books, and a 2011 prequel — also titled simply The Thing, and which narrates the plight of that doomed Norwegian team. This prequel is CGI-laden, and arguably tamer than Carpenter’s original. But the last few sequences in the film are much more over the top than Carpenter’s third act. Overall, the prequel falls flat compared to the ’82 version — highlighted by Rob Bottin’s grotesque puppetry and Kurt Russell’s increasingly volatile performance. Indeed, it can be argued that the ’82 film’s initially-negative reception earns it a spot amongst the greatest horror films of all time, as most of the negative reviews come back to the same points — 1) the special effects were repulsive, 2) the story was depressing. In other words, you didn’t want to be the men at that American outpost, nor did you root for the monster.  This was horror, quite simply, as it should be. Not romanticized or condoned, but merely endured. This makes The Thing a rarity in American horror cinema, especially during and after the “slasher” craze of the ’80s and ’90s. The monster isn’t there to be cheered for. It’s there to be reviled.

This was horror, quite simply, as it should be. Not romanticized or condoned, but merely endured. This makes The Thing a rarity in American horror cinema, especially during and after the “slasher” craze of the ’80s and ’90s. The monster isn’t there to be cheered for. It’s there to be reviled.

Carpenter himself was disheartened by the film’s initial reception and took it as a personal failure. It would be a few more years before he attempted to revisit his Apocalypse Trilogy with a slightly campier (but no less creepier) affair, which starred alumni from his pulp adventure Big Trouble in Little China, and featured not a shapeshifting alien, but the Prince of Darkness itself…