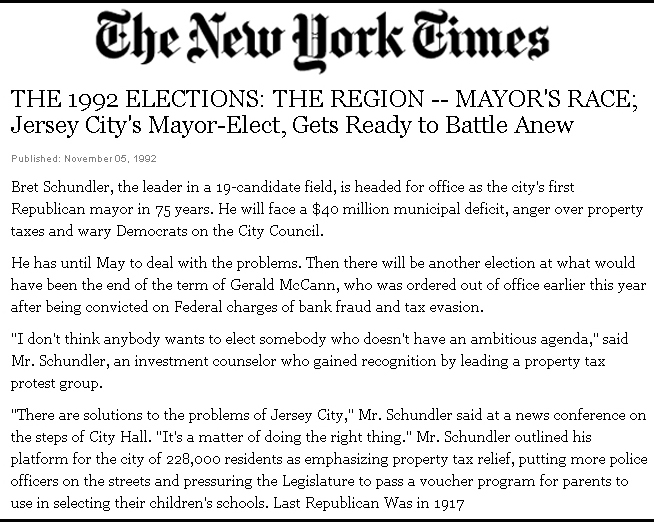

Who: Gregory Corrado is a Jersey City-based independent filmmaker and civil servant, who has lived in New Jersey’s second-largest city since 1988. In addition to writing/directing locally-shot films, Corrado is the Assistant City Manager for Jersey City — the second-highest non-elected official in city government. After moving to Jersey City, Corrado opened and ran Moochie’s Bistro, named for his wife Maureen, at the corner of Jersey and Columbus Avenues. Next, he entered New York University to study filmmaking. Corrado’s current duel cinematic/political careers would be shaped by the events of 1992, when he graduated NYU’s Graduate School of Dramatic Writing & Film with an MFA in screenwriting and directing, while one of his screenplays made him a finalist for the prestigious Nicholl Screenwriting Fellowship. Corrado hired an agent, but soon put his filmmaking ambitions on hold as the political star of friend Bret Schundler began to rise. In November of 1992, Schundler won a special election that made him the first Republican mayor of Jersey City in 75 years. Corrado proved instrumental in shaping how Schundler presented himself to Jersey City’s voters — directing several campaign television commercials for the Rebublican candidate in what had been a traditionally-Democratic stronghold. From 1992 to 2001 — when Schundler ran unsuccessfully for Governor of New Jersey — Corrado directed

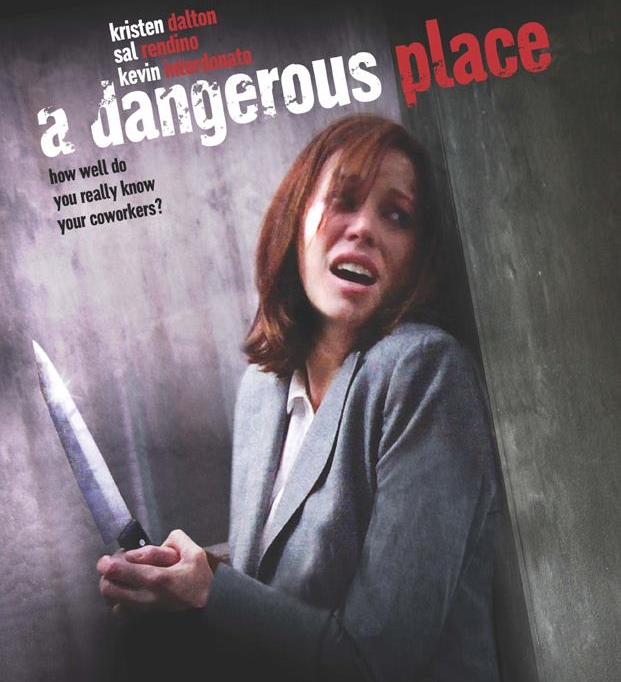

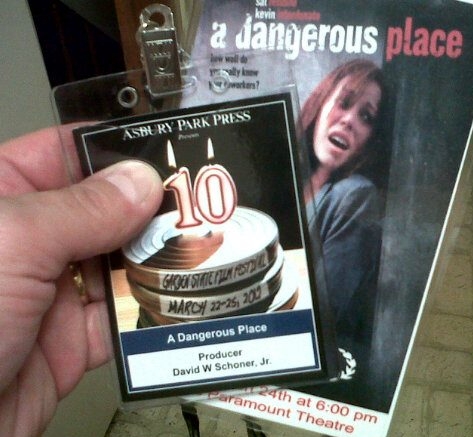

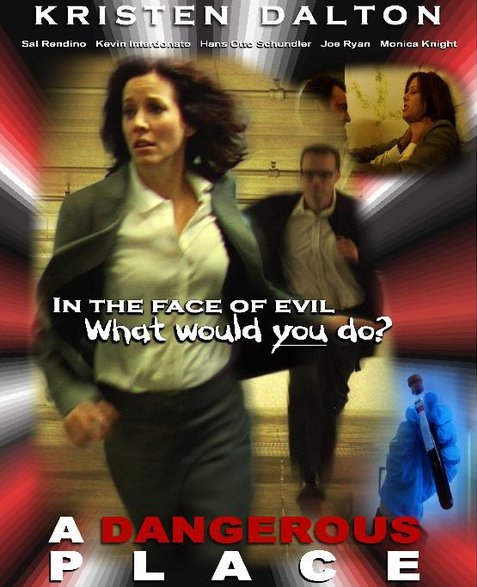

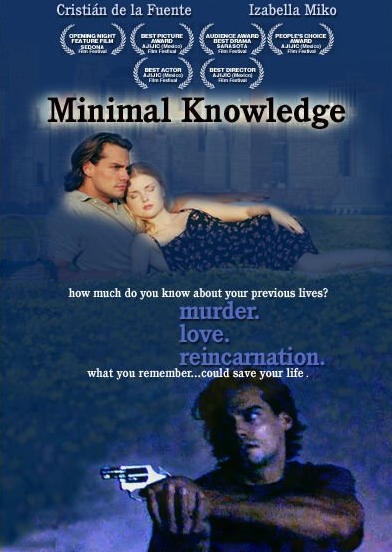

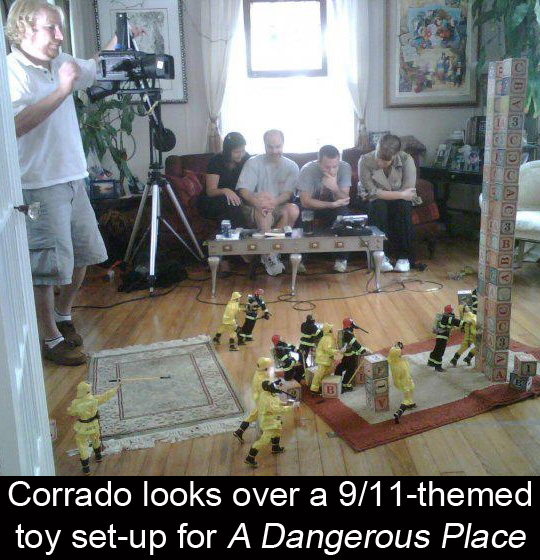

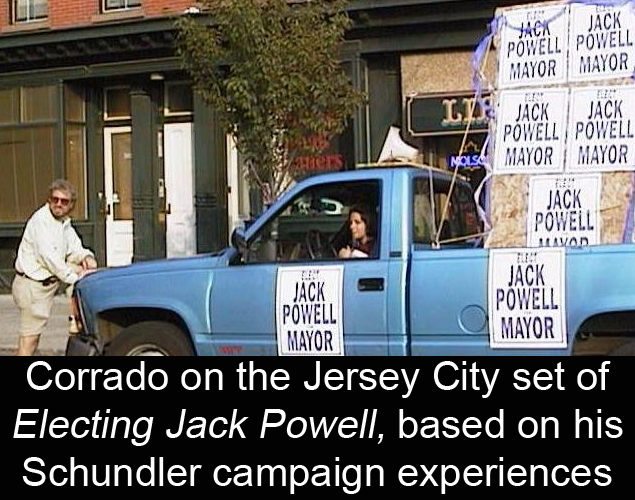

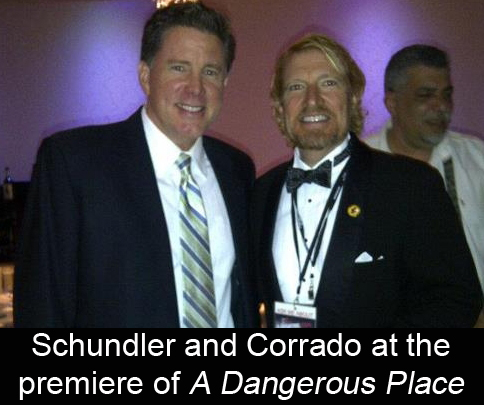

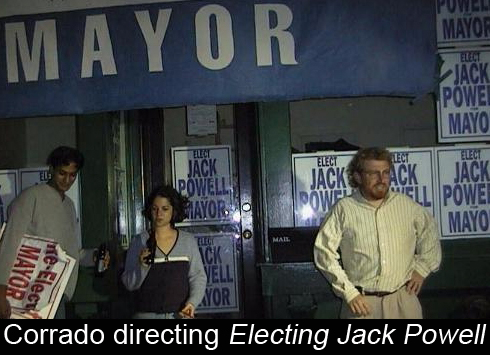

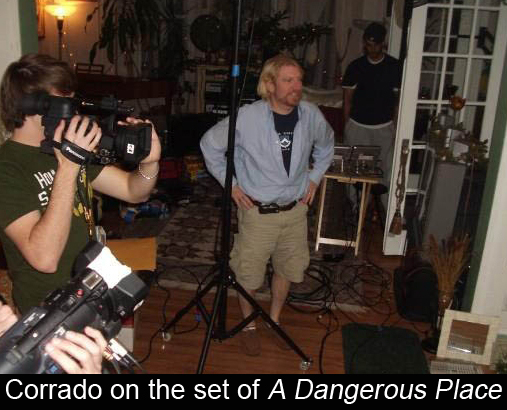

Who: Gregory Corrado is a Jersey City-based independent filmmaker and civil servant, who has lived in New Jersey’s second-largest city since 1988. In addition to writing/directing locally-shot films, Corrado is the Assistant City Manager for Jersey City — the second-highest non-elected official in city government. After moving to Jersey City, Corrado opened and ran Moochie’s Bistro, named for his wife Maureen, at the corner of Jersey and Columbus Avenues. Next, he entered New York University to study filmmaking. Corrado’s current duel cinematic/political careers would be shaped by the events of 1992, when he graduated NYU’s Graduate School of Dramatic Writing & Film with an MFA in screenwriting and directing, while one of his screenplays made him a finalist for the prestigious Nicholl Screenwriting Fellowship. Corrado hired an agent, but soon put his filmmaking ambitions on hold as the political star of friend Bret Schundler began to rise. In November of 1992, Schundler won a special election that made him the first Republican mayor of Jersey City in 75 years. Corrado proved instrumental in shaping how Schundler presented himself to Jersey City’s voters — directing several campaign television commercials for the Rebublican candidate in what had been a traditionally-Democratic stronghold. From 1992 to 2001 — when Schundler ran unsuccessfully for Governor of New Jersey — Corrado directed  more than 30 commercials for Schundler’s political campaigns. In the late ’90s, Corrado channeled his campaign experiences into the screenplay for his Jersey City-shot film, Electing Jack Powell, which he also directed. The film included cameos by several Jersey City politicians, but was never commercially released. It wasn’t until 2002 that Corrado released a debut feature, Minimal Knowledge. This would be one of many cinematic collaborations with producer David Schoner — the other half of Corrado Schoner Films, and Associate Director of the New Jersey Motion Picture & TV Commission. Their other feature film releases would later include 2007’s Stay, Go, Don’t Linger and 2008’s A 1000 Points of Light. Their latest independent film is the 2012 thriller, A Dangerous Place. This past March, the film had its New Jersey premiere during the 10th annual Garden State Film Festival in Asbury Park, where it took home the Home Grown Feature and Audience Choice awards. It was commercially released in late December 2012, available for sale or download online, with Corrado hoping to move 100,000 DVDs and downloads over six weeks — and sway cable TV networks like HBO or Showtime into picking up for the film to air. Camera In The Sun sat down with Corrado at his Jersey City home to discuss balancing careers in both film and politics, how his political TV ads helped sell Schundler to Jersey City voters, and his thoughts on shooting independent films in New Jersey.

more than 30 commercials for Schundler’s political campaigns. In the late ’90s, Corrado channeled his campaign experiences into the screenplay for his Jersey City-shot film, Electing Jack Powell, which he also directed. The film included cameos by several Jersey City politicians, but was never commercially released. It wasn’t until 2002 that Corrado released a debut feature, Minimal Knowledge. This would be one of many cinematic collaborations with producer David Schoner — the other half of Corrado Schoner Films, and Associate Director of the New Jersey Motion Picture & TV Commission. Their other feature film releases would later include 2007’s Stay, Go, Don’t Linger and 2008’s A 1000 Points of Light. Their latest independent film is the 2012 thriller, A Dangerous Place. This past March, the film had its New Jersey premiere during the 10th annual Garden State Film Festival in Asbury Park, where it took home the Home Grown Feature and Audience Choice awards. It was commercially released in late December 2012, available for sale or download online, with Corrado hoping to move 100,000 DVDs and downloads over six weeks — and sway cable TV networks like HBO or Showtime into picking up for the film to air. Camera In The Sun sat down with Corrado at his Jersey City home to discuss balancing careers in both film and politics, how his political TV ads helped sell Schundler to Jersey City voters, and his thoughts on shooting independent films in New Jersey.

What was your commercial approach to making A Dangerous Place, and where to premiere it?

We set out to make a commercial film. We didn’t set out to make a festival film. We wanted to hone our skills in making a commercial film. So, it’s a thriller. And a lot of what we might have put in a film that was a festival film, like our previous film Minimal Knowledge, we did not put in. So in Minimal Knowledge, the characters had philosophical conversations, because that’s what a cinephile would want to see. But we set out to make a commercial film, and sell it that way. And we picked the Garden State Film Festival for the premiere, because it’s our “hometown.” We were there when it first started, so it felt like being home. I’m originally from Long Island, but I’ve been living in New Jersey for 25 years. So it really is my home town. And David Schoner lives in Cedar Grove, and grew up in Belleville. He and his family are all from New Jersey. That’s why there were so many people at the premiere. It was also the festival’s 10th anniversary. So it was a great full-circle kind of thing — it’s their 10th anniversary, it’s in New Jersey, and all of our family can come. It was amazing. Diane Raver runs the festival and

We set out to make a commercial film. We didn’t set out to make a festival film. We wanted to hone our skills in making a commercial film. So, it’s a thriller. And a lot of what we might have put in a film that was a festival film, like our previous film Minimal Knowledge, we did not put in. So in Minimal Knowledge, the characters had philosophical conversations, because that’s what a cinephile would want to see. But we set out to make a commercial film, and sell it that way. And we picked the Garden State Film Festival for the premiere, because it’s our “hometown.” We were there when it first started, so it felt like being home. I’m originally from Long Island, but I’ve been living in New Jersey for 25 years. So it really is my home town. And David Schoner lives in Cedar Grove, and grew up in Belleville. He and his family are all from New Jersey. That’s why there were so many people at the premiere. It was also the festival’s 10th anniversary. So it was a great full-circle kind of thing — it’s their 10th anniversary, it’s in New Jersey, and all of our family can come. It was amazing. Diane Raver runs the festival and  originated it, and so there was that personal relationship. And we were so pleased to be able to bring the film there, because we weren’t showing it at festivals. Of course we applied to the Sundance Film Festival, and were told by people on the inside that we were short-listed. But there wasn’t enough art, and there wasn’t enough genre to get in. But it’s a very well-made film, so we’re very pleased with it.

originated it, and so there was that personal relationship. And we were so pleased to be able to bring the film there, because we weren’t showing it at festivals. Of course we applied to the Sundance Film Festival, and were told by people on the inside that we were short-listed. But there wasn’t enough art, and there wasn’t enough genre to get in. But it’s a very well-made film, so we’re very pleased with it.

A Dangerous Place is a commercical film, because it follows the patterns of what the major studios make. They’re going to get an audience. So all you’ve got to do is look at the top ten films in any given year, and figure out what they’re trying to do. So, what is that? Well, the number one thing you see are films that appeal to 14 year-old boys. So that’s either a comic book film, or an action film. The second thing you see would be a film that’s a crossover. So a 14 year-old would love it, and a 40 year-old would love it. And those are thrillers, like going  back to everything Harrison Ford made. And it runs the gamut. Then a subset of that would be a breakout comedy, like The Hangover or Bridesmaids. Those are comedies that appeal to 20-somethings — like a date comedy. And then there are those commercial films that appeal to an older crowd. That would be like The Bucket List. Those are really the different categories, and they’re simple. Just four of them, and that’s it. You could say horror films, because they do well. But they are almost never the top-five film. It’s rare that you’d see a top-five film be a horror film, like Paranormal Activity. But a notable exception would be The Silence of the Lambs. When I first saw that movie, I just loved it, and I said, “You know, this is a horror film made by an A-list director and an A-list cast.” That’s why it’s so good. If you did that to other horror films, they would be great. And I often wonder why people don’t do that. Why don’t they apply such skill to it?

back to everything Harrison Ford made. And it runs the gamut. Then a subset of that would be a breakout comedy, like The Hangover or Bridesmaids. Those are comedies that appeal to 20-somethings — like a date comedy. And then there are those commercial films that appeal to an older crowd. That would be like The Bucket List. Those are really the different categories, and they’re simple. Just four of them, and that’s it. You could say horror films, because they do well. But they are almost never the top-five film. It’s rare that you’d see a top-five film be a horror film, like Paranormal Activity. But a notable exception would be The Silence of the Lambs. When I first saw that movie, I just loved it, and I said, “You know, this is a horror film made by an A-list director and an A-list cast.” That’s why it’s so good. If you did that to other horror films, they would be great. And I often wonder why people don’t do that. Why don’t they apply such skill to it?

How does that compare to the approach you took with Minimal Knowledge and your other films?

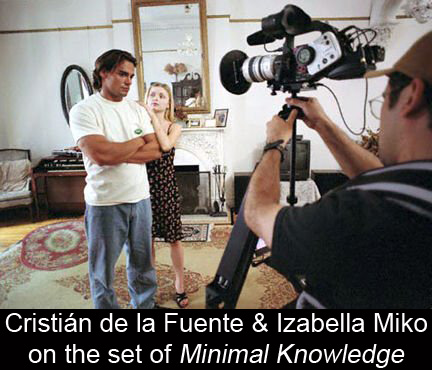

Minimal Knowledge was a screenplay that I wrote right out of grad school, and we cast Izabella Miko who had been in Coyote Ugly, and Cristián de la Fuente who was in Basic, which is a film  with John Travolta. And at that time, he was a huge star in South America. He’s from Chile, and was a fighter pilot in the Chilean air force, and was a big TV star there. So he came to Hollywood to break out, and he was in films like Basic and Driven with Sylvester Stallone. He was later, consequently, on Dancing With the Stars. Anyway, we put the film together pretty quick. I just contacted friends who had deep pockets who were willing to invest. It was mostly my classmates at Columbia — who did a lot better than me — that financed that film, and other friends that I knew. I think we made it for $200,000. It was cheap, low-budget, and the goal was to look for people who were on their way up. That’s not how we would cast a film today. But that’s how we cast that film.

with John Travolta. And at that time, he was a huge star in South America. He’s from Chile, and was a fighter pilot in the Chilean air force, and was a big TV star there. So he came to Hollywood to break out, and he was in films like Basic and Driven with Sylvester Stallone. He was later, consequently, on Dancing With the Stars. Anyway, we put the film together pretty quick. I just contacted friends who had deep pockets who were willing to invest. It was mostly my classmates at Columbia — who did a lot better than me — that financed that film, and other friends that I knew. I think we made it for $200,000. It was cheap, low-budget, and the goal was to look for people who were on their way up. That’s not how we would cast a film today. But that’s how we cast that film.

Minimal Knowledge is an art film, because they have philosophical discussions: “Why do we exist?  Why are we here?” and “Is it possible that we could live again?” Because it’s about a detective who falls in love with a woman who is reincarnated, and whether he will believe it. He’s a police detective, so he only believes in fact and reality. To even conceive that she’s reincarnated is impossible in his mind, but sets up a perfect place for them to have that conversation, because they’re in love. They have no choice but to be with each other, because they’re in love with each other. So if you’ve ever had a relationship, you understand what that’s like. If you’re together, you have to figure out things, like taking out the garbage — and you’re gonna hit head-to-head. Are you gonna vote Republican, or vote Democrat? What are you gonna do? So, you’re gonna have that conversation. Now, these people have an incredible conversation, since he’s based in fact, and she says that she’s reincarnated. What is he supposed to do with that? What is he gonna choose? Will he believe it, or not?

Why are we here?” and “Is it possible that we could live again?” Because it’s about a detective who falls in love with a woman who is reincarnated, and whether he will believe it. He’s a police detective, so he only believes in fact and reality. To even conceive that she’s reincarnated is impossible in his mind, but sets up a perfect place for them to have that conversation, because they’re in love. They have no choice but to be with each other, because they’re in love with each other. So if you’ve ever had a relationship, you understand what that’s like. If you’re together, you have to figure out things, like taking out the garbage — and you’re gonna hit head-to-head. Are you gonna vote Republican, or vote Democrat? What are you gonna do? So, you’re gonna have that conversation. Now, these people have an incredible conversation, since he’s based in fact, and she says that she’s reincarnated. What is he supposed to do with that? What is he gonna choose? Will he believe it, or not?

After we made Minimal Knowledge, we went out and made two small independent art films, since I wanted to develop my craft with directing actors before the camera, so that their acting was all good.  In some parts of Minimal Knowledge, I felt the acting was stale. It wasn’t because of them, but because of what I gave them. And so Stay, Go, Don’t Linger takes place in one room, and it’s about two brothers. The younger one is in an accident, and he can’t walk. He’s paralyzed, so the older brother considers killing him, because that’s really what the younger brother would want. And so, we’re watching the older brother come to that decision. Then, A 1000 Points of Light is three stories. It’s three people and their connection to their sexuality. The three stories are about how society tries to control sexuality. And whenever it does, it goes wrong. Everything is bad. And so, Stay, Go, Don’t Linger is about character study. That’s why it’s an art film. It’s about the older brother figuring out what to do about the younger brother. And then A 1000 Points of Light is about taking a theme that’s very strong, and very important — sexuality and freedom. How do I do that in three stories that are unrelated? That film is like a deck of cards.

In some parts of Minimal Knowledge, I felt the acting was stale. It wasn’t because of them, but because of what I gave them. And so Stay, Go, Don’t Linger takes place in one room, and it’s about two brothers. The younger one is in an accident, and he can’t walk. He’s paralyzed, so the older brother considers killing him, because that’s really what the younger brother would want. And so, we’re watching the older brother come to that decision. Then, A 1000 Points of Light is three stories. It’s three people and their connection to their sexuality. The three stories are about how society tries to control sexuality. And whenever it does, it goes wrong. Everything is bad. And so, Stay, Go, Don’t Linger is about character study. That’s why it’s an art film. It’s about the older brother figuring out what to do about the younger brother. And then A 1000 Points of Light is about taking a theme that’s very strong, and very important — sexuality and freedom. How do I do that in three stories that are unrelated? That film is like a deck of cards.

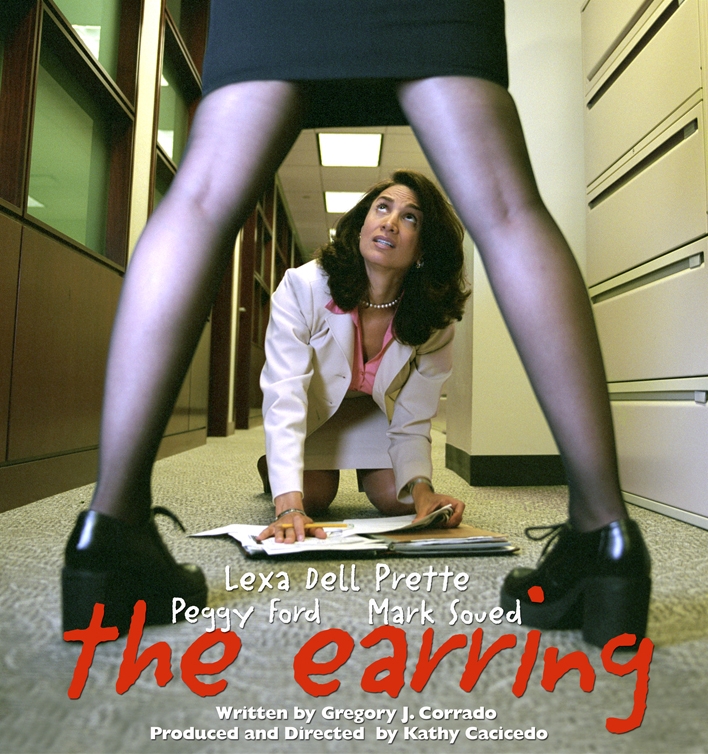

I wrote The Earring as a short for a woman who was our set photographer on Minimal Knowledge. She also did the poster, and she wanted to start doing narrative film. So I said, “I’ll write you a script.”  It did very well, because I think short films should be like The Twilight Zone. They should go along, and then all of a sudden, there’s a big twist in the end. And that’s a fun short, so that’s what happens in The Earring. It’s a flip, and it’s about a relationship. A husband and wife both work, and they have young children. The wife goes off to work, and at lunch she gets a text message to meet a guy. So she goes and meets the guy in a hotel room, and they make love, but she loses an earring there. And the earring is her mother-in-law’s earring. It wasn’t just a gift. It was an heirloom. She gets home, and she’s lost the earring and doesn’t know what to do. She’s just so upset. And her husband comes home and says, “I’ve found your earring.” So she’s very nervous, and says, “Where?” And he says, “Right where you left it, in the hotel room.” And then we find out that he’s the guy she met. They have this fantasy that they’ve had an affair. But actually, there isn’t one. So, it’s a girly movie.

It did very well, because I think short films should be like The Twilight Zone. They should go along, and then all of a sudden, there’s a big twist in the end. And that’s a fun short, so that’s what happens in The Earring. It’s a flip, and it’s about a relationship. A husband and wife both work, and they have young children. The wife goes off to work, and at lunch she gets a text message to meet a guy. So she goes and meets the guy in a hotel room, and they make love, but she loses an earring there. And the earring is her mother-in-law’s earring. It wasn’t just a gift. It was an heirloom. She gets home, and she’s lost the earring and doesn’t know what to do. She’s just so upset. And her husband comes home and says, “I’ve found your earring.” So she’s very nervous, and says, “Where?” And he says, “Right where you left it, in the hotel room.” And then we find out that he’s the guy she met. They have this fantasy that they’ve had an affair. But actually, there isn’t one. So, it’s a girly movie.

A Dangerous Place is a thriller about a damsel in distress who overcomes all of the obstacles and succeeds. And what sets it apart from the other thrillers is that she has a very strong personal story. Her husband was killed on 9/11. So she’s dealing with her own self-denial, and she won’t put that behind her to fulfill her relationship with her son. Her son is a victim of her grief, and he reacts by not talking to her. She’s not communicating to him, because she won’t let her dead husband go. That part of the film is why I wrote the film. A Dangerous Place has the theme of overcoming grief from 9/11. The locomotive driving the film is a terrorist story. But it’s really about how she fails her son by holding onto something, and not letting it go.

How did you to come to collaborate with David Schoner?

I met David through a mutual acquaintance, Bill LaRosa, who is the Cultural Affairs Director for Hudson County. And I remember meeting David, which was wild, because his energy is so high. I  couldn’t believe it. I had to move away from him, because his energy was so high. Then later, I observed that David makes a cup of coffee feel nervous.

couldn’t believe it. I had to move away from him, because his energy was so high. Then later, I observed that David makes a cup of coffee feel nervous.

David’s asset is organizing our shoots, and organizing on what day something is gonna be shot. He has very strong organizational skills. He has a deep network of people who have been interns for him at the Commission, and their friends. He also speaks at universities and high schools and middle schools about filmmaking. That’s part of his job. So, there’s that network. But what the Film Commission does for a living is that it’s a liaison between filmmakers and the 500 municipalities in New Jersey who each have different rules for filmmaking. So they go through the Film Commission, because it’s a mess otherwise. So that’s what he does every day. Now, that’s not necessarily an asset to us making films — except to say that he knows every town, and where we would shoot.

What’s the value of shooting in New Jersey?

New Jersey is a place where real things happen. So just by luck, we happen to live in a state that when filmmakers want to say things are “real,” they place it here. If you have somebody who’s struggling and poor, they might put him in New Jersey. If you have someone who’s a mobster who’s not glamorized, then it’s Tony Soprano. That’s an advantage. But the advantage for me is that I just happen to live here, and have lots of friends. You know, I could be in Florida and still be making movies with people I know.

New Jersey is a place where real things happen. So just by luck, we happen to live in a state that when filmmakers want to say things are “real,” they place it here. If you have somebody who’s struggling and poor, they might put him in New Jersey. If you have someone who’s a mobster who’s not glamorized, then it’s Tony Soprano. That’s an advantage. But the advantage for me is that I just happen to live here, and have lots of friends. You know, I could be in Florida and still be making movies with people I know.

New Jersey offers you everything you want within an hour’s drive. You have downtown here, which is brownstones. It’s a historic district. You walk two blocks away, and you could be in Manhattan, if you don’t look at the river. If you walk one more block, you’re on a major river. You drive just 40 minutes west, and you’re on a cornfield, and you can’t see anything but corn. And we have all the suburbs. So, Northern New Jersey offers you everything you want within an hour’s drive.

Are you satisfied with how Jersey City is portrayed in feature films and television?

I am satisfied, and I’ll tell you why. I don’t think Jersey City has a large profile by itself. I think people have to know that it even exists. So it’s not like someone in Ohio is watching a movie, and says, “Oh, that’s Jersey City. That’s terrible.” No. We’re almost like Toronto in that sense. People come here and shoot here, and it doesn’t take place in Jersey City. It’s not like, “This story is a Jersey City story.” No. We’re a backdrop for some other place. So I don’t think we get a bad reputation by the films that are shot here. I don’t think that is viable. I’d say this, though. On the flip side, culturally it appears to me that there are two epicenters in America. There is Brooklyn, and Jersey City. And if you scratch the surface on any person you ever meet, they are either somehow related to those two places, or know someone who is from there. So it’s amazing how deep Jersey City is culturally in America. But in film and TV, it’s not. I don’t think it really exists.

I am satisfied, and I’ll tell you why. I don’t think Jersey City has a large profile by itself. I think people have to know that it even exists. So it’s not like someone in Ohio is watching a movie, and says, “Oh, that’s Jersey City. That’s terrible.” No. We’re almost like Toronto in that sense. People come here and shoot here, and it doesn’t take place in Jersey City. It’s not like, “This story is a Jersey City story.” No. We’re a backdrop for some other place. So I don’t think we get a bad reputation by the films that are shot here. I don’t think that is viable. I’d say this, though. On the flip side, culturally it appears to me that there are two epicenters in America. There is Brooklyn, and Jersey City. And if you scratch the surface on any person you ever meet, they are either somehow related to those two places, or know someone who is from there. So it’s amazing how deep Jersey City is culturally in America. But in film and TV, it’s not. I don’t think it really exists.

How did you become involved with Brett Schundler’s political campaigns?

The way I was raised was that you always give back to the community. My father was very involved. Not in politics, but in community service. In fact, he was a voracious reader, and our library was underserved in the community. So he ran for the library board trustee for one purpose: to build a new library. He won, and they built a new library. But he passed away before it was finished. So they named the multipurpose room after him, which was a great honor. So, that’s the way we were raised. You’re supposed to be part of the community. When I moved to Jersey City in 1988, onto York Street with my old college roommate, I joined the Van Vorst Park Association, because that was the local community group. I saw it advertised on the telephone polls, so I joined, and I went to the meetings, and they were boring. But that’s what you do. And Brett Schundler was on the board, so I got to meet him. And after these meetings, there would be a coffee and wine thing, and we would all talk. That’s how we got to know each other. Consequently, I fell in love with [wife] Moochie, and we decided to open a restaurant. And after a year in business, I went to grad school. But while I was there, Brett ran for State Senate in the district that has Jersey City and south to Bayonne. So he asked me if I would make TV commercials for him, and that’s what I did.

The way I was raised was that you always give back to the community. My father was very involved. Not in politics, but in community service. In fact, he was a voracious reader, and our library was underserved in the community. So he ran for the library board trustee for one purpose: to build a new library. He won, and they built a new library. But he passed away before it was finished. So they named the multipurpose room after him, which was a great honor. So, that’s the way we were raised. You’re supposed to be part of the community. When I moved to Jersey City in 1988, onto York Street with my old college roommate, I joined the Van Vorst Park Association, because that was the local community group. I saw it advertised on the telephone polls, so I joined, and I went to the meetings, and they were boring. But that’s what you do. And Brett Schundler was on the board, so I got to meet him. And after these meetings, there would be a coffee and wine thing, and we would all talk. That’s how we got to know each other. Consequently, I fell in love with [wife] Moochie, and we decided to open a restaurant. And after a year in business, I went to grad school. But while I was there, Brett ran for State Senate in the district that has Jersey City and south to Bayonne. So he asked me if I would make TV commercials for him, and that’s what I did.

At the time, I was at the dramatic writing program in the Tisch School of the Arts. But I had actually been accepted to the film school years prior, and I didn’t go. So I had talked to the dean, and said, “I really want to be a film director. But I’m not a kid. I’m 29, and I want to know if this is gonna work.” And she told me, “Most of the kids that graduate NYU’s film school hang lamps and do the technical things. They don’t become the directors. If you want to become a professional director, you really should learn how to write. Because that’s the quickest way in.” Although, here we are 20 years later, and I’m not there. But that was the advice she gave me. So I didn’t go to film school, and I applied to the writing program instead. But I was wait-listed the first year, because they only accepted 12. So the second year, I got in. And when I got in to the writing program, I went back up to the film school, but that dean was gone by that time. I said, “I’d like to make a movie.” Now, they let me double-major in both film and screenwriting. But the film school said, “Give us the script. Let’s see what you’re gonna shoot, before we give you access to our equipment, and to our students who have to shoot it.” So I

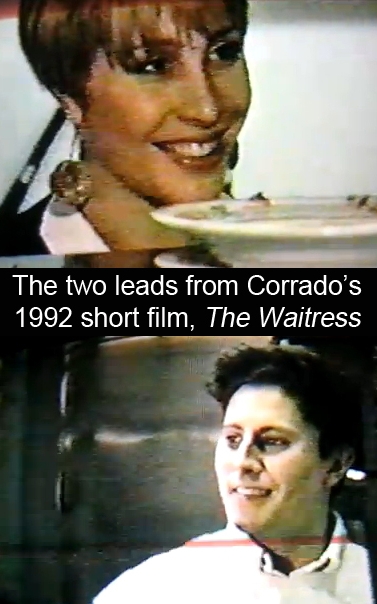

At the time, I was at the dramatic writing program in the Tisch School of the Arts. But I had actually been accepted to the film school years prior, and I didn’t go. So I had talked to the dean, and said, “I really want to be a film director. But I’m not a kid. I’m 29, and I want to know if this is gonna work.” And she told me, “Most of the kids that graduate NYU’s film school hang lamps and do the technical things. They don’t become the directors. If you want to become a professional director, you really should learn how to write. Because that’s the quickest way in.” Although, here we are 20 years later, and I’m not there. But that was the advice she gave me. So I didn’t go to film school, and I applied to the writing program instead. But I was wait-listed the first year, because they only accepted 12. So the second year, I got in. And when I got in to the writing program, I went back up to the film school, but that dean was gone by that time. I said, “I’d like to make a movie.” Now, they let me double-major in both film and screenwriting. But the film school said, “Give us the script. Let’s see what you’re gonna shoot, before we give you access to our equipment, and to our students who have to shoot it.” So I gave them a script called The Waitress. It was about a waitress at Moochie’s falling in love with the bartender, and they actually have a philosophical conversation. The woman who played the waitress, Cyndi Dawson, posted it up online. I had lost it. But I watch it now, and I’m like, “Wow, this is amazing.” Then after that, they let me make a full student film the following year. It was called Getting Bleak, and it’s about these two yuppies who go out into the country looking for antiques. But they dress down, because they don’t want the antique dealer to think that they’re yuppies, and overcharge them. So, they have a scam going. They go into Pennsylvania, and visit places that aren’t antiques stores — more like these consignment places selling junk. But they’re really looking for quality stuff. So they go on the road, change into their scruffy stuff, and then go into this place. And as they’re about to open the door, they see a kitten in the doorway drinking milk out of a small bowl. So they walk in, and look around. And there’s an old guy there saying, “Hey, how are ya, folks?” But they don’t buy anything, and go back out. And the wife says to the husband, “Did you see the bowl?” He says, “What bowl?” She says, “The cat‘s bowl. The cat was drinking out of an 1850 bowl.” So they’re fired up, and go back into the place, and say, “You know, we want to buy your cat.” The guy says, “The cat’s not for sale.” They say, “We have to have the cat.” So eventually, the owner takes good money for the cat. And they say, “Well, we have to take the bowl, of course. Because the cat has to have his bowl.” They argue, and the guy says, “No, you can’t have the bowl. Absolutely not.” So they leave without the bowl, but they have the cat. And the wife is pissed, because the husband came up with this stupid idea that didn’t work. Now, we cut back to the shop. The old guy goes in the back room, and there’s like ten cats. So he picks up another cat, and puts the bowl out at the front door with this cat. That was my thesis film, and it was around 8 minutes.

gave them a script called The Waitress. It was about a waitress at Moochie’s falling in love with the bartender, and they actually have a philosophical conversation. The woman who played the waitress, Cyndi Dawson, posted it up online. I had lost it. But I watch it now, and I’m like, “Wow, this is amazing.” Then after that, they let me make a full student film the following year. It was called Getting Bleak, and it’s about these two yuppies who go out into the country looking for antiques. But they dress down, because they don’t want the antique dealer to think that they’re yuppies, and overcharge them. So, they have a scam going. They go into Pennsylvania, and visit places that aren’t antiques stores — more like these consignment places selling junk. But they’re really looking for quality stuff. So they go on the road, change into their scruffy stuff, and then go into this place. And as they’re about to open the door, they see a kitten in the doorway drinking milk out of a small bowl. So they walk in, and look around. And there’s an old guy there saying, “Hey, how are ya, folks?” But they don’t buy anything, and go back out. And the wife says to the husband, “Did you see the bowl?” He says, “What bowl?” She says, “The cat‘s bowl. The cat was drinking out of an 1850 bowl.” So they’re fired up, and go back into the place, and say, “You know, we want to buy your cat.” The guy says, “The cat’s not for sale.” They say, “We have to have the cat.” So eventually, the owner takes good money for the cat. And they say, “Well, we have to take the bowl, of course. Because the cat has to have his bowl.” They argue, and the guy says, “No, you can’t have the bowl. Absolutely not.” So they leave without the bowl, but they have the cat. And the wife is pissed, because the husband came up with this stupid idea that didn’t work. Now, we cut back to the shop. The old guy goes in the back room, and there’s like ten cats. So he picks up another cat, and puts the bowl out at the front door with this cat. That was my thesis film, and it was around 8 minutes.

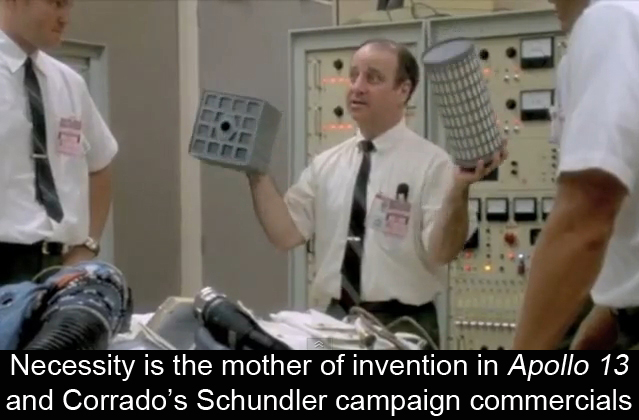

Directing my first campaign commercial was a great challenge — like, “OK, what are we gonna do here?” It reminds me of Apollo 13, where Ed Harris tells them to build a filter. So they go in a room, dump all this stuff on the table, and say, “OK, we have to connect this square thing to this round thing.” I love that scene. This is all they have. Figure it out. Failure is not an option. And when you’re about to write something, you’re like, “Alright, who’s my audience?” It’s a puzzle. And you say, “How do I figure out where I’m gonna go?” So when we did the commercials, at the time Brett had a very good feel for populist political communication. I’d say he’s gotten away from that feel. Back then though, he had a handle on the pulse of populist feeling, and on what people felt were problems they wanted to be addressed.

Directing my first campaign commercial was a great challenge — like, “OK, what are we gonna do here?” It reminds me of Apollo 13, where Ed Harris tells them to build a filter. So they go in a room, dump all this stuff on the table, and say, “OK, we have to connect this square thing to this round thing.” I love that scene. This is all they have. Figure it out. Failure is not an option. And when you’re about to write something, you’re like, “Alright, who’s my audience?” It’s a puzzle. And you say, “How do I figure out where I’m gonna go?” So when we did the commercials, at the time Brett had a very good feel for populist political communication. I’d say he’s gotten away from that feel. Back then though, he had a handle on the pulse of populist feeling, and on what people felt were problems they wanted to be addressed.  And more importantly, what they thought the answer was. So when you set up a commercial, it’s like a Dylan Thomas poem. It starts very strong. You know, “The force that threw the green fuse is the force that gives me life.” It’s very strong, like “Whoa! Excuse me?” You really want to be right on it. So we wanted to start the commercial very strong with something that hits your feelings. And the great thing about political commercials is that they can be as corny as you want. Because even though they might be building your brand, which is your candidate — at the same time, they really are guttural. You want people to really feel. That’s all. It’s usually melodramatic. So, Obama: “Hope.” Like the world is ending? The world is not ending. That’s pretty melodramatic. It’s Hope. It’s, “Oh my God, if we don’t vote for him, we’re hopeless.” That’s what you want to do in a political commercial. You can’t sell soap with hope. It’s gotta work. “This soap doesn’t clean you. It’s the promise of cleaning you.”

And more importantly, what they thought the answer was. So when you set up a commercial, it’s like a Dylan Thomas poem. It starts very strong. You know, “The force that threw the green fuse is the force that gives me life.” It’s very strong, like “Whoa! Excuse me?” You really want to be right on it. So we wanted to start the commercial very strong with something that hits your feelings. And the great thing about political commercials is that they can be as corny as you want. Because even though they might be building your brand, which is your candidate — at the same time, they really are guttural. You want people to really feel. That’s all. It’s usually melodramatic. So, Obama: “Hope.” Like the world is ending? The world is not ending. That’s pretty melodramatic. It’s Hope. It’s, “Oh my God, if we don’t vote for him, we’re hopeless.” That’s what you want to do in a political commercial. You can’t sell soap with hope. It’s gotta work. “This soap doesn’t clean you. It’s the promise of cleaning you.”

The election for mayor was in November of ’92. It was tumultuous in Jersey City, because of the faulty reevaluation of property taxes in the city. We had people losing their homes. We also had a recession in 1991, which hit Jersey City very hard, because we’re a bedroom community to lower Manhattan.  The recession hit Wall Street and advertising, which was downtown Jersey City. And we still had a lot of old-school literally-old people living downtown, still in their brick row houses, who would be dead now to be honest. They were people living on Social Security, living on York Street in houses that now sell for a million dollars. So, it was really tumultuous. I mean, we had people in the streets protesting with a coffin, where they put the taxpayer in the coffin. People were really mobilized, because overnight their taxes doubled, or more. So people were losing their homes, you’ve got a faulty reval, and you’ve got a recession at the same time. Also, crime was a big issue here. Very big. It was taxes and crime. It really felt like Jersey City was out of control. People were worried about walking home at night. And then, you have [former-Mayor] Gerry McCann going to jail. He can’t even run the city, because he’s trying to defend himself in court. And then he loses. So it’s the perfect storm that led to this revolution. But what precipitated that revolution was the feeling that the city was falling apart. And we were newcomers. We were only here 3 or 4 years. And the feeling was, “Oh my God, what is gonna happen now?” Only 68% of the city paid their real estate taxes. So that means that over 30% chose to break the law, and put their property at risk of losing it, because they had no faith in the government. It was just crazy. So then there were 19 mayoral candidates, because Jersey City — especially at that time — loved politics. It was a real game. And with even a cursory view of Jersey City history, it was a revolving door of corruption. So you had people think it was an advantage somehow, like, “I’m gonna be mayor, and that’s a ticket to success.” And you had many people involved in the ’92 race thinking of that. It definitely was a machine town. It’s currently not, but it can be a machine town if you want it to be. I think that can happen anywhere democracy is practiced. It’s not particular to Jersey City. That’s a notion that Jersey City people love, because we romanticize it. But that’s not the case. Anyway, Brett had done very well in the ’91 State Senate race. He ran as a Republican, and almost beat Edward O’Connor, who later became a Superior Court judge. We shouldn’t have had a chance against him. And we brought that energy to the ’92 campaign for Mayor.

The recession hit Wall Street and advertising, which was downtown Jersey City. And we still had a lot of old-school literally-old people living downtown, still in their brick row houses, who would be dead now to be honest. They were people living on Social Security, living on York Street in houses that now sell for a million dollars. So, it was really tumultuous. I mean, we had people in the streets protesting with a coffin, where they put the taxpayer in the coffin. People were really mobilized, because overnight their taxes doubled, or more. So people were losing their homes, you’ve got a faulty reval, and you’ve got a recession at the same time. Also, crime was a big issue here. Very big. It was taxes and crime. It really felt like Jersey City was out of control. People were worried about walking home at night. And then, you have [former-Mayor] Gerry McCann going to jail. He can’t even run the city, because he’s trying to defend himself in court. And then he loses. So it’s the perfect storm that led to this revolution. But what precipitated that revolution was the feeling that the city was falling apart. And we were newcomers. We were only here 3 or 4 years. And the feeling was, “Oh my God, what is gonna happen now?” Only 68% of the city paid their real estate taxes. So that means that over 30% chose to break the law, and put their property at risk of losing it, because they had no faith in the government. It was just crazy. So then there were 19 mayoral candidates, because Jersey City — especially at that time — loved politics. It was a real game. And with even a cursory view of Jersey City history, it was a revolving door of corruption. So you had people think it was an advantage somehow, like, “I’m gonna be mayor, and that’s a ticket to success.” And you had many people involved in the ’92 race thinking of that. It definitely was a machine town. It’s currently not, but it can be a machine town if you want it to be. I think that can happen anywhere democracy is practiced. It’s not particular to Jersey City. That’s a notion that Jersey City people love, because we romanticize it. But that’s not the case. Anyway, Brett had done very well in the ’91 State Senate race. He ran as a Republican, and almost beat Edward O’Connor, who later became a Superior Court judge. We shouldn’t have had a chance against him. And we brought that energy to the ’92 campaign for Mayor.

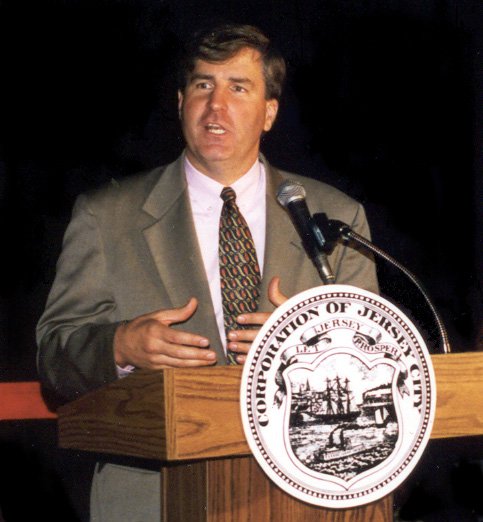

That first election in November ’92 was a special election to replace McCann. Then Bret had to run for re-election. And that’s actually why I started working at City Hall. Bret asked me for help, so I moved into City Hall with him. The general election was in May ’93, and they tried to say that Bret was a Wall  Street shark who was an outsider trying to take over the city. They also brought Jesse Jackson in to say that he was a racist. And it didn’t sell. We ignored that. You don’t want to confront it face-to-face, because you legitimize it. Instead, we kept hammering home what was wrong with the city. Bret’s campaign was based on “The city is a mess. I’m a good guy. I’m a smart guy. I’m a millionaire, so I’m not gonna steal from you, like every other politician did. And because I’m smart, I think I can fix it. I’m kind of a quiet guy. But if you ask me a question, I’m gonna answer it. Even if it takes 20 minutes and bores you to tears, I’m gonna answer your question. I’m not gonna avoid it.” So that sold very well. Where’s the core in that? “My city is falling apart. I don’t care about national politics. I am afraid that I may not have a house. My house may be worth nothing tomorrow. I can’t pay my taxes. If I call the police, they don’t come. I don’t care what you say to me — ‘you’ being who I’ve always dealt with — I’m gonna go with this guy [Schundler].” And we won 69% of the vote. So, it was a landslide.

Street shark who was an outsider trying to take over the city. They also brought Jesse Jackson in to say that he was a racist. And it didn’t sell. We ignored that. You don’t want to confront it face-to-face, because you legitimize it. Instead, we kept hammering home what was wrong with the city. Bret’s campaign was based on “The city is a mess. I’m a good guy. I’m a smart guy. I’m a millionaire, so I’m not gonna steal from you, like every other politician did. And because I’m smart, I think I can fix it. I’m kind of a quiet guy. But if you ask me a question, I’m gonna answer it. Even if it takes 20 minutes and bores you to tears, I’m gonna answer your question. I’m not gonna avoid it.” So that sold very well. Where’s the core in that? “My city is falling apart. I don’t care about national politics. I am afraid that I may not have a house. My house may be worth nothing tomorrow. I can’t pay my taxes. If I call the police, they don’t come. I don’t care what you say to me — ‘you’ being who I’ve always dealt with — I’m gonna go with this guy [Schundler].” And we won 69% of the vote. So, it was a landslide.

Why did Schundler’s campaign pursue TV commercials in those local mayoral races?

That was the strategy that I developed for Bret. We had more ads than the other candidates. Not because they didn’t have the money. They just didn’t have the vision. Also, we were young and brash. We were gonna try stuff that other people didn’t, because we didn’t have a history. We weren’t coming from the political realm. We were gonna think out of the box, because we didn’t have a box. Anyway, advertising is about iteration. There’s an old rule of thumb, where you need to see something seven times before you remember it. We all know that, because we see the same  damn commercial on different channels. It was intuitive. We wanted to be in front of as many people as we possibly could, as many times as we could, repeating the same thing. There was a retailer, Crazy Eddie — “His prices are insane!” There’s no way you didn’t know who he was, and what he was selling. As opposed to “Af-lac.” No one knew what that was. Everyone knew Aflac, because of the little duck. But you didn’t know what the hell they were selling. I bet if you go out on the street right now and ask people, they wouldn’t know what Aflac sells. So like that Apollo 13 example, you say, “This is what we have. How do we make it most effective?” So I’m a pretty smart guy, and I felt it was intuitive that we would want to be in front of everyone. And there was a change in media at that time — a change in the delivery of information. And we took advantage of this new media: cable television. So I got the cable rate card, looked at all of the stations, and said to Bret, “These are the stations we should go with, including Yankee games. We should pick the spots that we want to be in, even if it’s gonna be a little more expensive, so that we can’t turn the TV on without seeing you.” And he agreed with that, and that’s what we did. We were on ESPN and MSG — which was the Yankee channel then — and so we were on during Yankee games. We were not on broadcast TV at all. We were only on cable. I told Bret, “No broadcast, because it’s too expensive.” Yeah, we were gonna miss people who only watched broadcast. And in the ’90’s, that was still true. There were people who only watched broadcast, and didn’t have cable. I would surmise that somebody who was 60 in 1992 was still of the mindset that “I’ll use my antenna upstairs, and watch local Channel 11.” But we were gonna hit those people with printed material. So I felt strongly that broadcast would skew older, because everyone who was 40 or younger was gonna have cable. That would be the norm. I’ll tell you, when we went campaigning, Brett and I knocked on doors in the housing projects in Lafayette Gardens. And we’d go into people’s homes, and they had several TV’s, and everyone had cable. So I’m in a project, thinking that it’s gonna be abject poverty, totally naive. No, it’s like a regular apartment, and everyone had a TV in their living room, a TV in their bedroom, and they all had cable. So most people had already gone to cable, which was great, because we had a bunch of mailing pieces going out. We would go out with another mailer every two weeks. And it’s hard when you’re the politician to realize the value in all of those mailers. But it’s great when you’re the end user. I told Bret, “This is what we do. You get your mail, and you go through it, and you’re looking at that political mailer, and then throwing it in the garbage. But in the time your mind takes to figure out that it’s a political ad, we need to send your message. So the message has already been sent during the time when you were making that decision.” When I see pieces that come into our house that don’t work that way, it’s a real downer. Because people throw them away, without getting the message, and it’s sad. With our mailers, you’d get one about crime, taxes, the arts. They were aggressive in how often you got them, and were also across different subjects, and supported by the TV commercials. And those commercials would be placed in such a way that you couldn’t help but see them, because they were in prime time, and were on all of those different channels. And by law, they had to give us a lower rate, because we were political. So we got the political rate card, but they limit how much you can buy. They don’t want anyone to buy 100% of that time, because they want to be open to the other candidates. So even though we were restricted by that, we still were everywhere. It was great. We actually did a 60-second spot. Nobody does that anymore. It was, “Who is Bret?” And it went from his education, onward. It was a real “This is a good guy” message. We showed him sweeping his steps, because he does that. He’s a fastidious person. He walks out of his house, and if there’s garbage on the street, he actually picks it up before he gets to his car. I mean, he can’t help himself. He went to Harvard, so we showed the diploma. And he’s a very studious guy, reading. People loved to talk to him. He’s that rare politician, I’d say. It’s almost dangerous. Because if you ever ask him a policy question, you’re in trouble. Don’t be in a hurry, because he actually answers the question. When I first went out door-to-door with him, people would ask him questions. And that’s when I knew Brett was certain to be mayor of everybody in Jersey City — not just downtown. We went everywhere but downtown, because we wanted to make sure that those folks in other neighborhoods knew that. And Brett is very sincere. He’s almost too sincere, and that came across very well. He was also tireless when he was campaigning. And when we were in different parts of the city, we were always very well-received. At first it would be like, “What are you doing knocking on my door from downtown? You don’t belong here. The way you talk, you don’t have nothin’ to do with this. What are you doing in Greenville?” But he was like, “This is where I am.” And I was next to him when we were in the projects. He was gallant in the idea that he didn’t care where he was going. He was gonna meet everybody he could. And I remember this one time, it’s indelible, this young Hispanic mother asked him a question. He started giving the answer. And then he kept giving the answer… and he kept giving the answer… and he’s telling her the entire answer. And I could see in her eyes — at first it was “Wow, this handsome guy is talking to me.” And then, “This guy is still answering.” And then her eyes were like, “I don’t think I can hear any more of this answer.” As opposed to most politicians, where they give you the quick answer, and then they move on. So going out campaigning with him always took forever. You couldn’t get him out of a room. So the strategy with the commercials we made showed him talking to people. It was his education. It was his roots in the community, because he was the president of the local civic association. We even had him driving by the Statue of Liberty.

damn commercial on different channels. It was intuitive. We wanted to be in front of as many people as we possibly could, as many times as we could, repeating the same thing. There was a retailer, Crazy Eddie — “His prices are insane!” There’s no way you didn’t know who he was, and what he was selling. As opposed to “Af-lac.” No one knew what that was. Everyone knew Aflac, because of the little duck. But you didn’t know what the hell they were selling. I bet if you go out on the street right now and ask people, they wouldn’t know what Aflac sells. So like that Apollo 13 example, you say, “This is what we have. How do we make it most effective?” So I’m a pretty smart guy, and I felt it was intuitive that we would want to be in front of everyone. And there was a change in media at that time — a change in the delivery of information. And we took advantage of this new media: cable television. So I got the cable rate card, looked at all of the stations, and said to Bret, “These are the stations we should go with, including Yankee games. We should pick the spots that we want to be in, even if it’s gonna be a little more expensive, so that we can’t turn the TV on without seeing you.” And he agreed with that, and that’s what we did. We were on ESPN and MSG — which was the Yankee channel then — and so we were on during Yankee games. We were not on broadcast TV at all. We were only on cable. I told Bret, “No broadcast, because it’s too expensive.” Yeah, we were gonna miss people who only watched broadcast. And in the ’90’s, that was still true. There were people who only watched broadcast, and didn’t have cable. I would surmise that somebody who was 60 in 1992 was still of the mindset that “I’ll use my antenna upstairs, and watch local Channel 11.” But we were gonna hit those people with printed material. So I felt strongly that broadcast would skew older, because everyone who was 40 or younger was gonna have cable. That would be the norm. I’ll tell you, when we went campaigning, Brett and I knocked on doors in the housing projects in Lafayette Gardens. And we’d go into people’s homes, and they had several TV’s, and everyone had cable. So I’m in a project, thinking that it’s gonna be abject poverty, totally naive. No, it’s like a regular apartment, and everyone had a TV in their living room, a TV in their bedroom, and they all had cable. So most people had already gone to cable, which was great, because we had a bunch of mailing pieces going out. We would go out with another mailer every two weeks. And it’s hard when you’re the politician to realize the value in all of those mailers. But it’s great when you’re the end user. I told Bret, “This is what we do. You get your mail, and you go through it, and you’re looking at that political mailer, and then throwing it in the garbage. But in the time your mind takes to figure out that it’s a political ad, we need to send your message. So the message has already been sent during the time when you were making that decision.” When I see pieces that come into our house that don’t work that way, it’s a real downer. Because people throw them away, without getting the message, and it’s sad. With our mailers, you’d get one about crime, taxes, the arts. They were aggressive in how often you got them, and were also across different subjects, and supported by the TV commercials. And those commercials would be placed in such a way that you couldn’t help but see them, because they were in prime time, and were on all of those different channels. And by law, they had to give us a lower rate, because we were political. So we got the political rate card, but they limit how much you can buy. They don’t want anyone to buy 100% of that time, because they want to be open to the other candidates. So even though we were restricted by that, we still were everywhere. It was great. We actually did a 60-second spot. Nobody does that anymore. It was, “Who is Bret?” And it went from his education, onward. It was a real “This is a good guy” message. We showed him sweeping his steps, because he does that. He’s a fastidious person. He walks out of his house, and if there’s garbage on the street, he actually picks it up before he gets to his car. I mean, he can’t help himself. He went to Harvard, so we showed the diploma. And he’s a very studious guy, reading. People loved to talk to him. He’s that rare politician, I’d say. It’s almost dangerous. Because if you ever ask him a policy question, you’re in trouble. Don’t be in a hurry, because he actually answers the question. When I first went out door-to-door with him, people would ask him questions. And that’s when I knew Brett was certain to be mayor of everybody in Jersey City — not just downtown. We went everywhere but downtown, because we wanted to make sure that those folks in other neighborhoods knew that. And Brett is very sincere. He’s almost too sincere, and that came across very well. He was also tireless when he was campaigning. And when we were in different parts of the city, we were always very well-received. At first it would be like, “What are you doing knocking on my door from downtown? You don’t belong here. The way you talk, you don’t have nothin’ to do with this. What are you doing in Greenville?” But he was like, “This is where I am.” And I was next to him when we were in the projects. He was gallant in the idea that he didn’t care where he was going. He was gonna meet everybody he could. And I remember this one time, it’s indelible, this young Hispanic mother asked him a question. He started giving the answer. And then he kept giving the answer… and he kept giving the answer… and he’s telling her the entire answer. And I could see in her eyes — at first it was “Wow, this handsome guy is talking to me.” And then, “This guy is still answering.” And then her eyes were like, “I don’t think I can hear any more of this answer.” As opposed to most politicians, where they give you the quick answer, and then they move on. So going out campaigning with him always took forever. You couldn’t get him out of a room. So the strategy with the commercials we made showed him talking to people. It was his education. It was his roots in the community, because he was the president of the local civic association. We even had him driving by the Statue of Liberty.

What impact did your time making political TV ads have on your current approach to filmmaking?

NYU taught me how to communicate visually. But the commercials were about being focused on audience, and what they will receive from what you make. And I also believed, even prior to my going to film school, that all art is political. It’s a Marxist quote. And so I like to say, “If Spike Lee had made E.T., it wouldn’t have happened in a White suburban upper-class Southern California place.” So the thing I love about writing and filmmaking is that it has a point of view. Every film has a political point of view. And during that period in the ’90’s, it was clear we were having an influence on what people were thinking with the commercials. And that’s exactly the thing I love about filmmaking. You can challenge the status quo, or you can reinforce the status quo. There’s a direct line between the two. And I think every filmmaker should decide that. Because I watch films, and I know when they haven’t decided that. You can feel it in the film — whether the viewpoint is confused, or the viewpoint is cavalier. I mean, that film has such an opportunity to influence people. Why would you not intentionally choose that. Because it doesn’t have to be heavy. A comedy can do that. All art is political. You either reinforce that status quo, or you

NYU taught me how to communicate visually. But the commercials were about being focused on audience, and what they will receive from what you make. And I also believed, even prior to my going to film school, that all art is political. It’s a Marxist quote. And so I like to say, “If Spike Lee had made E.T., it wouldn’t have happened in a White suburban upper-class Southern California place.” So the thing I love about writing and filmmaking is that it has a point of view. Every film has a political point of view. And during that period in the ’90’s, it was clear we were having an influence on what people were thinking with the commercials. And that’s exactly the thing I love about filmmaking. You can challenge the status quo, or you can reinforce the status quo. There’s a direct line between the two. And I think every filmmaker should decide that. Because I watch films, and I know when they haven’t decided that. You can feel it in the film — whether the viewpoint is confused, or the viewpoint is cavalier. I mean, that film has such an opportunity to influence people. Why would you not intentionally choose that. Because it doesn’t have to be heavy. A comedy can do that. All art is political. You either reinforce that status quo, or you  challenge the status quo. Period. Like how you choose characters in your film. Why not have a handle on that, and decide what you’re gonna say? If the main characters are a couple, and one has a brother who’s gay, and they treat him like he’s a pariah, that’s a statement. If they treat him as just a regular guy, but he’s gay, that’s a statement. If your characters smoke cigarettes, what are you saying? So that’s the direct line. It’s a powerful thing when you make political commercials, and you’re given the free reign to make ones that are effective. Because I have made some commercials since then where I’ve been restrained. I knew they weren’t going to be effective, because they were those cookie cutter friendly kind of things that don’t really work. Because as I said about Dylan Thomas, you have to come out strong. You have to give people a reason to listen to what you have to say. But what most politicians want to see is a soft version of themselves.

challenge the status quo. Period. Like how you choose characters in your film. Why not have a handle on that, and decide what you’re gonna say? If the main characters are a couple, and one has a brother who’s gay, and they treat him like he’s a pariah, that’s a statement. If they treat him as just a regular guy, but he’s gay, that’s a statement. If your characters smoke cigarettes, what are you saying? So that’s the direct line. It’s a powerful thing when you make political commercials, and you’re given the free reign to make ones that are effective. Because I have made some commercials since then where I’ve been restrained. I knew they weren’t going to be effective, because they were those cookie cutter friendly kind of things that don’t really work. Because as I said about Dylan Thomas, you have to come out strong. You have to give people a reason to listen to what you have to say. But what most politicians want to see is a soft version of themselves.

Apart from campaigning and City Hall work, what delayed your getting back to feature films?

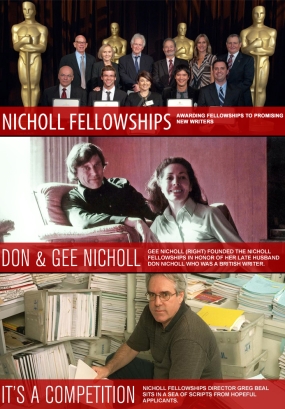

What happened actually is not pretty. I was at NYU, and I did amazingly well. I was a finalist for the Nicholl Fellowship, which is awarded by the Academy Awards every year. They gave it out to five writers. And out of 4,000 entries, I was in the top ten. From that top ten, they pick five. And my script was The Troubles. But this was in ’92, so it was during Bret’s campaign for mayor. Anyway, I was chased by three agents and a manager. I signed with an agent at Writers & Artists, which is a bi-coastal agency. It’s really good. But then I stopped writing. What happened was I had a failure of my own personal belief in myself. When I was at NYU, I always had been a good student. I had the belief that I would be a good student, and so I was. I’d gone to Columbia, so I was a smart kid, and believed in myself to do that. So I rose to the top of the crop, and I did very well. Then this Academy Awards contest happened, and I went right to the top, and I got an agent. But then as soon as I got out of NYU, I didn’t have a paradigm for success. My paradigm at that point was, “I’m just a kid from Long Island, and there’s no way I can be a famous screenwriter. That’s bullshit. Not you.” And so I got scared, and I just stopped writing. But three years later, I said to myself, “What the hell are you doing?” I absolutely enjoyed my work in City Hall, and it was exciting what we did with Bret, and how we changed the city. It is a much better place than it was before he was elected — without a doubt, without controversy, it’s so much better.

What happened actually is not pretty. I was at NYU, and I did amazingly well. I was a finalist for the Nicholl Fellowship, which is awarded by the Academy Awards every year. They gave it out to five writers. And out of 4,000 entries, I was in the top ten. From that top ten, they pick five. And my script was The Troubles. But this was in ’92, so it was during Bret’s campaign for mayor. Anyway, I was chased by three agents and a manager. I signed with an agent at Writers & Artists, which is a bi-coastal agency. It’s really good. But then I stopped writing. What happened was I had a failure of my own personal belief in myself. When I was at NYU, I always had been a good student. I had the belief that I would be a good student, and so I was. I’d gone to Columbia, so I was a smart kid, and believed in myself to do that. So I rose to the top of the crop, and I did very well. Then this Academy Awards contest happened, and I went right to the top, and I got an agent. But then as soon as I got out of NYU, I didn’t have a paradigm for success. My paradigm at that point was, “I’m just a kid from Long Island, and there’s no way I can be a famous screenwriter. That’s bullshit. Not you.” And so I got scared, and I just stopped writing. But three years later, I said to myself, “What the hell are you doing?” I absolutely enjoyed my work in City Hall, and it was exciting what we did with Bret, and how we changed the city. It is a much better place than it was before he was elected — without a doubt, without controversy, it’s so much better.  And I enjoy my job now, as Assistant City Manager. I’m the second-highest non-elected official in the city. But I awoke three years later saying, “You know, my real dream is to be a filmmaker, and I blew it. So, let’s go back at it.” And that’s what I’ve been doing. But the approach I’ve taken is to learn how to direct — really know how to do it. And I was working at that for years, but I still was afraid of becoming it. It wasn’t until I started working on my own spiritual life, who I am as a man, that I’ve now become ready to take this on. Because what we do is we get in the way of our own dreams. We have this dream in our heart, and then we figure out ways how we don’t deserve it, we can’t do it, we’re not the one to make it, somebody knows something that we don’t know. So in the last three years I’ve really changed, and it has made all the difference in the world. There’s a quotation by Muhammad Ali that goes like this: “It is the repetition of affirmation that leads to belief. And once a belief becomes a deeply held conviction, then things begin to happen.” And that’s the development that I needed to make a change in my life.

And I enjoy my job now, as Assistant City Manager. I’m the second-highest non-elected official in the city. But I awoke three years later saying, “You know, my real dream is to be a filmmaker, and I blew it. So, let’s go back at it.” And that’s what I’ve been doing. But the approach I’ve taken is to learn how to direct — really know how to do it. And I was working at that for years, but I still was afraid of becoming it. It wasn’t until I started working on my own spiritual life, who I am as a man, that I’ve now become ready to take this on. Because what we do is we get in the way of our own dreams. We have this dream in our heart, and then we figure out ways how we don’t deserve it, we can’t do it, we’re not the one to make it, somebody knows something that we don’t know. So in the last three years I’ve really changed, and it has made all the difference in the world. There’s a quotation by Muhammad Ali that goes like this: “It is the repetition of affirmation that leads to belief. And once a belief becomes a deeply held conviction, then things begin to happen.” And that’s the development that I needed to make a change in my life.