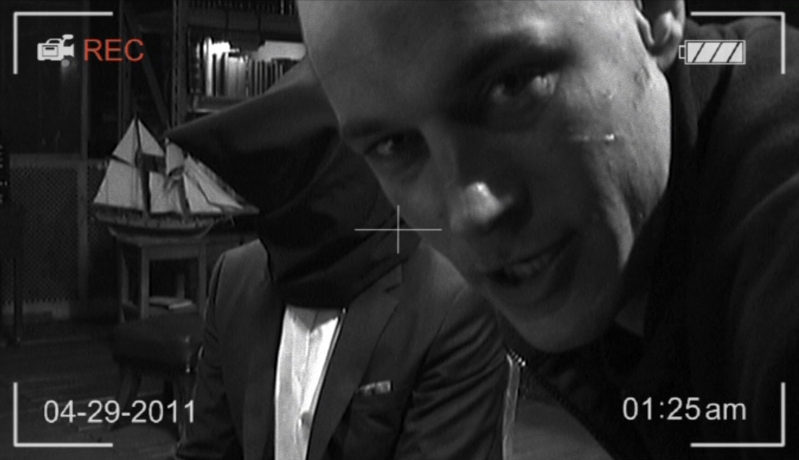

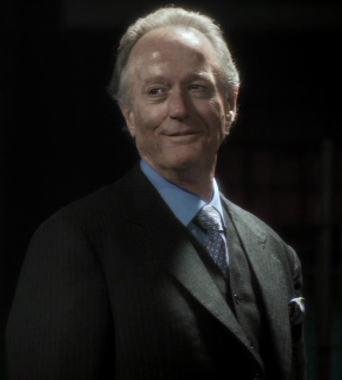

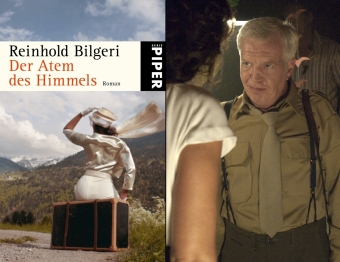

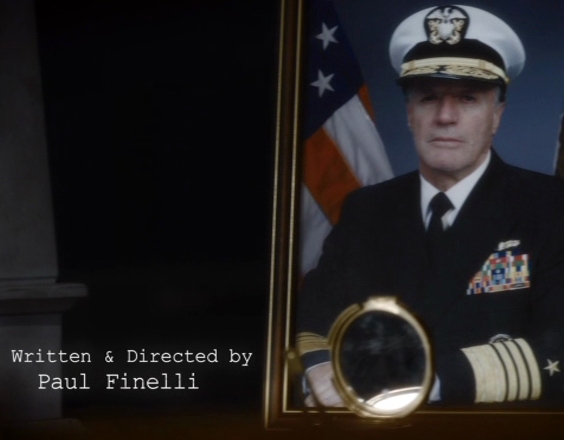

Who: Paul Finelli is a Pittsburgh-based filmmaker who recently made his feature directorial debut with Harodim, which opens a theatrical run in Europe on October 25th. Prior to Harodim, Finelli had spent several years working as a screenwriter in Los Angeles. Despite several close calls, none of his L.A.-era screenplays were adapted to the big screen, which led him to eventually relocate to Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. But after taking a small acting role in singer/filmmaker Reinhold Bilgeri’s 2010 film, The Breath of Heaven, Finelli met and partnered with producer Thomas Feldkircher to negotiate with Austria’s Terra Mater Factual Studios to make Harodim. The film blends feature-style narrative with news and documentary footage. The plot centers on a former naval intelligence officer, Lazarus Fell (Travis Fimmel) who captures the world’s most wanted terrorist (Michael Desante), only to have his worldview challenged by his father Solomon Fell (Peter Fonda). Camera In The Sun sat down with Finelli at his home in Pittsburgh to discuss Harodim’s production, the career that brought him to Austria, and his new outlook on cinema.

Who: Paul Finelli is a Pittsburgh-based filmmaker who recently made his feature directorial debut with Harodim, which opens a theatrical run in Europe on October 25th. Prior to Harodim, Finelli had spent several years working as a screenwriter in Los Angeles. Despite several close calls, none of his L.A.-era screenplays were adapted to the big screen, which led him to eventually relocate to Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. But after taking a small acting role in singer/filmmaker Reinhold Bilgeri’s 2010 film, The Breath of Heaven, Finelli met and partnered with producer Thomas Feldkircher to negotiate with Austria’s Terra Mater Factual Studios to make Harodim. The film blends feature-style narrative with news and documentary footage. The plot centers on a former naval intelligence officer, Lazarus Fell (Travis Fimmel) who captures the world’s most wanted terrorist (Michael Desante), only to have his worldview challenged by his father Solomon Fell (Peter Fonda). Camera In The Sun sat down with Finelli at his home in Pittsburgh to discuss Harodim’s production, the career that brought him to Austria, and his new outlook on cinema.

[Publishers Note: Photos from Harodim courtesy of Terra Mater Factual Studios]

Finelli’s director’s statement regarding the narrative/documentary structure of Harodim:

I started research for the screenplay that would ultimately become Harodim. But how to do it? How to make a feature film that would convey the real issues and questions I was encountering without resorting to the same old, trite, overused and, in this case, totally inappropriate formula of “fictionalizing” the subject by creating characters “loosely based” on “real historical personalities”? Or using all the predictable devices I have come to hate in contemporary films dealing with controversial subjects – changing the names, dates, places and events to resemble something like reality while not actually engaging in it. How could I invest the story with the kind of reality endemic to a great documentary while charging it with elements that would meet the criteria of a great entertainment film, however

I started research for the screenplay that would ultimately become Harodim. But how to do it? How to make a feature film that would convey the real issues and questions I was encountering without resorting to the same old, trite, overused and, in this case, totally inappropriate formula of “fictionalizing” the subject by creating characters “loosely based” on “real historical personalities”? Or using all the predictable devices I have come to hate in contemporary films dealing with controversial subjects – changing the names, dates, places and events to resemble something like reality while not actually engaging in it. How could I invest the story with the kind of reality endemic to a great documentary while charging it with elements that would meet the criteria of a great entertainment film, however  unusual or confrontational the subject matter might be?

unusual or confrontational the subject matter might be?

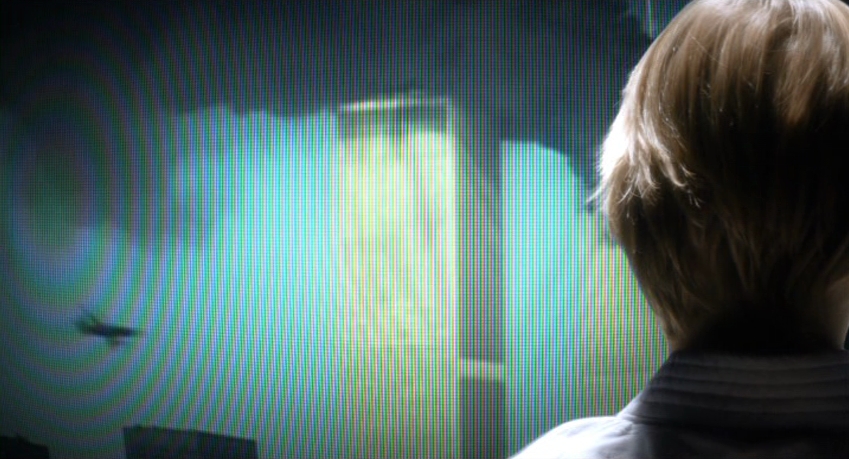

Then it hit me. Why not do both? Why not use the kind of real world, fact-based point of view conveyed by a documentary through the use of actual news, historical, archive and documentary footage to enhance and punctuate the fictional portion of the film’s narrative and, through this marriage, blur the line between fact and fiction to a point where both would become suspect and each would be elevated to another narrative level completely. I had seen documentary footage used in a limited way in features before, as in Oliver Stone’s great film, JFK, but I had never seen it used to the level I intended to use it. In the case of this story, its use would also serve a secondary purpose, an even more subversive one – that of indicting the media with its own material. The media, after all, has become the landscape of accepted reality in our technological age. If you see it on television, it  must be true.

must be true.

To make this idea work effectively, the characters would have to be compelling in a whole other way, a much more human, yet simultaneously metaphorical way. Whether a believer or a non-believer in the “conspiracy” elements of the story, you must be able to relate to these people on some basic human level, to understand the circumstances which have brought them here, to this room at this present moment. The live action would be shot very much like a stage play, most of it confined to one location, where the interplay between ideas and emotions would be enhanced by a feeling of intimacy in a place and a state of mind existing outside the realms of normal reality. The familiar documentary and news footage would add a sense of global scale to that intimacy and provide us with a view of the “real” world existing somewhere outside, light years away in another dimension and as close to us as the TV screen in our living room.

As I researched Osama bin Laden, I began to see something interesting or, more accurately, the lack of something interesting in virtually everything that has been written about him. There was literally no indication of any actual human being behind the almost super human qualities being ascribed to this mysterious will-o’-the-wisp boogie man. He was already a fictional character. My job would be to reverse that. To find the man behind the media-created image. To discover human flaws and, yes, even virtues behind the mythological monster the world media and its governments had created to serve their own ends.

As I researched Osama bin Laden, I began to see something interesting or, more accurately, the lack of something interesting in virtually everything that has been written about him. There was literally no indication of any actual human being behind the almost super human qualities being ascribed to this mysterious will-o’-the-wisp boogie man. He was already a fictional character. My job would be to reverse that. To find the man behind the media-created image. To discover human flaws and, yes, even virtues behind the mythological monster the world media and its governments had created to serve their own ends.

Knowing that he must be there somewhere if he, in fact, ever existed at all, I was out to find a living person at the heart of the most notorious terrorist on earth. I would not mention his name in the film however, preferring that the viewer make that discovery on his own. By the time the revelation of who the character really is has occurred, the natural proclivity to prejudge him would have already been replaced by an interest in his story, by the kind of subliminal transference that says ‘What if I was born into his world? Would I have done anything differently? Would I have been able to?’

The news that Osama bin Laden had been killed by American forces on May 1 of [2011], in a strange way, came as no surprise. The media’s 9/11 script needed an ending and that ending should serve a political agenda as well as provide emotional closure to a public traumatized by the decade long residue of 9/11. Whatever the real truth behind the story, it was predictable that bin Laden’s death would eventually have to be written in. What shook me up a bit, however, was how closely the narrative for my script, written the previous year in 2010, had mirrored the “facts” as they were reported by the world media. I had gotten too many things right for comfort, even down to the Navy SEAL involvement in the operation. It seemed that the projections I had made about the “conspiratorial” motives in the story were not so far off base and that may be the scariest thing of all about this film. It is not enough, however, to simply illustrate how a conspiracy of this magnitude might have been conducted. It is more important to discover why. The characters of Lazarus and Solomon would serve a purpose in the film’s narrative far beyond the obvious biblical, and not so obvious masonic, archetypal references that their names imply. They would balance the light and dark, the rational and the emotional mind existing at the core of human nature, operating the engine and governor behind its pre-eminent survival instincts.

The news that Osama bin Laden had been killed by American forces on May 1 of [2011], in a strange way, came as no surprise. The media’s 9/11 script needed an ending and that ending should serve a political agenda as well as provide emotional closure to a public traumatized by the decade long residue of 9/11. Whatever the real truth behind the story, it was predictable that bin Laden’s death would eventually have to be written in. What shook me up a bit, however, was how closely the narrative for my script, written the previous year in 2010, had mirrored the “facts” as they were reported by the world media. I had gotten too many things right for comfort, even down to the Navy SEAL involvement in the operation. It seemed that the projections I had made about the “conspiratorial” motives in the story were not so far off base and that may be the scariest thing of all about this film. It is not enough, however, to simply illustrate how a conspiracy of this magnitude might have been conducted. It is more important to discover why. The characters of Lazarus and Solomon would serve a purpose in the film’s narrative far beyond the obvious biblical, and not so obvious masonic, archetypal references that their names imply. They would balance the light and dark, the rational and the emotional mind existing at the core of human nature, operating the engine and governor behind its pre-eminent survival instincts.

Lazarus would represent a kind of purity, of innocence, in the face of the terrible imperatives of unchecked power. The idealized American, he is a soldier but he is also a dutiful son, in a way, a mirror image of the Terrorist with his own struggle filtered through Western eyes and Western beliefs, as much a victim to unquestioning faith as his perceived Muslim enemy. His journey toward truth should be the journey of the viewer, preconditioned by the media and the fictional landscape of fear and patriotism that it has fostered in the service of its financial and political masters’ ascendant power, in which no crime, no lie, no secret, whatever its scale, exists without justification. Solomon would represent the deadly rationale behind that power, eminently reasonable, eminently wise, an enlightened philosopher

Lazarus would represent a kind of purity, of innocence, in the face of the terrible imperatives of unchecked power. The idealized American, he is a soldier but he is also a dutiful son, in a way, a mirror image of the Terrorist with his own struggle filtered through Western eyes and Western beliefs, as much a victim to unquestioning faith as his perceived Muslim enemy. His journey toward truth should be the journey of the viewer, preconditioned by the media and the fictional landscape of fear and patriotism that it has fostered in the service of its financial and political masters’ ascendant power, in which no crime, no lie, no secret, whatever its scale, exists without justification. Solomon would represent the deadly rationale behind that power, eminently reasonable, eminently wise, an enlightened philosopher  secure in the rightness of his path no matter what price must be exacted to see it realized. But he is also a father who wants his vision to be shared by his son, regardless of how his son must be conditioned to accept and embrace it. The end will justify the means. It is a truth about human beings that no one, however cold or inhuman his actions may appear to others, thinks of himself as a villain. The greatest evils in history have been perpetrated by men who saw a higher necessity, a higher good, behind every action , however heinous, however violent, however cruel.

secure in the rightness of his path no matter what price must be exacted to see it realized. But he is also a father who wants his vision to be shared by his son, regardless of how his son must be conditioned to accept and embrace it. The end will justify the means. It is a truth about human beings that no one, however cold or inhuman his actions may appear to others, thinks of himself as a villain. The greatest evils in history have been perpetrated by men who saw a higher necessity, a higher good, behind every action , however heinous, however violent, however cruel.

This film will do more than just examine these ideas. It will hopefully serve as a means to de-condition the viewer away from the simplistic and convenient view of history our media-obsessed culture has given him, perhaps add a much-needed human element to the digital information bytes we have all come to accept as truth in the modern world. This is not a political film. It is an experiment in the paradigm altering power of cinema. I am not an activist or a conspiracy theorist. I am a filmmaker. The ideas examined in this film hold no intentions, illusions or agenda of being put forward as the basis for any kind of political platform or polemic. Instead, I hope they will serve as a mirror for the best and the worst in all of us and a means of separating the two.

What was the casting process for Harodim?

The first person to really react to the script was Michael Desante. He said, “I have to do this movie.” It was sort of passed to him through his attorney or manager in L.A. He actually went so far as to record a demo that he put together with some weird makeup, and sent it out to be considered for the role — which I thought was really cool. I mean, he wanted it that bad. And Michael Desante is very well-respected within the acting community in L.A. for a long time. He’s been in a number of things, like The Hurt Locker. You know, he’s one of those guys who’s a known actor, but not a movie star. And at the time, I was talking with an old friend and colleague of mine, Michael Grais. He wrote Poltergeist, wrote and produced Poltergeist II, and was somebody I had worked with in L.A. a lot. I optioned my first screenplay to Michael and his partner Mark Victor back in ’95. He’s a great writer, and so we’ve kind of maintained a friendship for a while. And for a while, it looked like he was going to come along as one of the producers. But this was a project that would require us to defer our fees until after the film got done, and he really wasn’t

The first person to really react to the script was Michael Desante. He said, “I have to do this movie.” It was sort of passed to him through his attorney or manager in L.A. He actually went so far as to record a demo that he put together with some weird makeup, and sent it out to be considered for the role — which I thought was really cool. I mean, he wanted it that bad. And Michael Desante is very well-respected within the acting community in L.A. for a long time. He’s been in a number of things, like The Hurt Locker. You know, he’s one of those guys who’s a known actor, but not a movie star. And at the time, I was talking with an old friend and colleague of mine, Michael Grais. He wrote Poltergeist, wrote and produced Poltergeist II, and was somebody I had worked with in L.A. a lot. I optioned my first screenplay to Michael and his partner Mark Victor back in ’95. He’s a great writer, and so we’ve kind of maintained a friendship for a while. And for a while, it looked like he was going to come along as one of the producers. But this was a project that would require us to defer our fees until after the film got done, and he really wasn’t  willing to do that. So Michael had just written a script that Peter Fonda is still trying to get the money to direct, called Border Wars. So Michael gave him a copy of the script, and Fonda got back to us and said that he’d love to do it. And the reason that I wanted Peter Fonda was because he’s a known icon of radical films. He has this image, especially in Europe, as the free-spirited American outlaw from Easy Rider. They still think of him that way. So it was more than just an acting choice. I really liked that iconic stature that Peter Fonda had. Finally, for the role of Lazarus, I knew that I had to have somebody who could carry the film. There was just no two ways about it. So I got in touch with my friend Ivana Chubbuck, who is considered like the top acting coach in cinema today. She’s worked with everybody. I studied with her for years in L.A. as an actor, but more as a writer, and maybe one day as a director. So Ivana certainly was a huge influence on me for a long time. And I hadn’t talked to her in years, since I’d been in Pittsburgh. And I called her up and said, “Look Ivana, I’m in a jam. I really need somebody who can play this role.” She read the script, flipped out, and then got back to me and said, “This is an amazing project. I’ve got the guy.” That

willing to do that. So Michael had just written a script that Peter Fonda is still trying to get the money to direct, called Border Wars. So Michael gave him a copy of the script, and Fonda got back to us and said that he’d love to do it. And the reason that I wanted Peter Fonda was because he’s a known icon of radical films. He has this image, especially in Europe, as the free-spirited American outlaw from Easy Rider. They still think of him that way. So it was more than just an acting choice. I really liked that iconic stature that Peter Fonda had. Finally, for the role of Lazarus, I knew that I had to have somebody who could carry the film. There was just no two ways about it. So I got in touch with my friend Ivana Chubbuck, who is considered like the top acting coach in cinema today. She’s worked with everybody. I studied with her for years in L.A. as an actor, but more as a writer, and maybe one day as a director. So Ivana certainly was a huge influence on me for a long time. And I hadn’t talked to her in years, since I’d been in Pittsburgh. And I called her up and said, “Look Ivana, I’m in a jam. I really need somebody who can play this role.” She read the script, flipped out, and then got back to me and said, “This is an amazing project. I’ve got the guy.” That  guy was Travis Fimmel, who is a real up-and-coming actor in L.A. now, and he had a great look. With Ivana’s assurances and her coaching, I knew he was gonna be what we were looking for. Michael Desante got together and read with him, and said, “Great! This is the guy.” And so, that’s how we did it. All this was cobbled together very quickly. Because when you’ve got producers willing to put the money up, the longer this stuff drags on, the more time they’ve got to think, “Well, do I really want to do this?” So it was one of those things where we just had to pray the chemistry would work well with these three guys. I’d never had a chance to go to L.A. and actually do any rehearsals with them, or readings. I just had to hope that it would work out. Michael Desante got married that month, and so he was in Lebanon. So apart from Travis doing the reading with Michael, the three of them had not met at all. I mean, there was a lot of dialogue involved in this. And one hallmark in Peter Fonda’s career is if he delivers ten lines in a movie, that’s a lot. And this was exactly the opposite. He had to deliver a lot of dialogue. So there were uncertainties on my part about it, and I only really had three days to rehearse them before we

guy was Travis Fimmel, who is a real up-and-coming actor in L.A. now, and he had a great look. With Ivana’s assurances and her coaching, I knew he was gonna be what we were looking for. Michael Desante got together and read with him, and said, “Great! This is the guy.” And so, that’s how we did it. All this was cobbled together very quickly. Because when you’ve got producers willing to put the money up, the longer this stuff drags on, the more time they’ve got to think, “Well, do I really want to do this?” So it was one of those things where we just had to pray the chemistry would work well with these three guys. I’d never had a chance to go to L.A. and actually do any rehearsals with them, or readings. I just had to hope that it would work out. Michael Desante got married that month, and so he was in Lebanon. So apart from Travis doing the reading with Michael, the three of them had not met at all. I mean, there was a lot of dialogue involved in this. And one hallmark in Peter Fonda’s career is if he delivers ten lines in a movie, that’s a lot. And this was exactly the opposite. He had to deliver a lot of dialogue. So there were uncertainties on my part about it, and I only really had three days to rehearse them before we  started shooting. Fonda didn’t even arrive until one week into the shoot. The producers had put aside two days for me with him and the other actors. But a lot of that was spent with me in Fonda’s hotel room, rewriting dialogue for him. You know, Fonda was pretty astute on how he wanted to deliver the role, and I talked to him a bit about it. Because I think he was originally coming in and thinking that the point behind that role was to be this very powerful spook. And I talked to him about it and said, “No, I think that’s the wrong way to approach it. This guy is a father who wants his son to understand the things he’s done, and why. And he’s in a lot of pain from these things that he’s done. He’s never relished it. He’s done it because he thought it was his duty, and now he’s basically tired. He’s been worn down by carrying this power all this time.” And Peter really did understand that, and I think he brought a kind of vulnerability to that role that was necessary. The problem was that we were on such a tight shooting schedule. I wish I would have had another five or six days with him to really work on it. I mean, he came in and turned in a great performance. But I wanted that extra level, and I knew that it was there. It was the same thing with Travis Fimmel.

started shooting. Fonda didn’t even arrive until one week into the shoot. The producers had put aside two days for me with him and the other actors. But a lot of that was spent with me in Fonda’s hotel room, rewriting dialogue for him. You know, Fonda was pretty astute on how he wanted to deliver the role, and I talked to him a bit about it. Because I think he was originally coming in and thinking that the point behind that role was to be this very powerful spook. And I talked to him about it and said, “No, I think that’s the wrong way to approach it. This guy is a father who wants his son to understand the things he’s done, and why. And he’s in a lot of pain from these things that he’s done. He’s never relished it. He’s done it because he thought it was his duty, and now he’s basically tired. He’s been worn down by carrying this power all this time.” And Peter really did understand that, and I think he brought a kind of vulnerability to that role that was necessary. The problem was that we were on such a tight shooting schedule. I wish I would have had another five or six days with him to really work on it. I mean, he came in and turned in a great performance. But I wanted that extra level, and I knew that it was there. It was the same thing with Travis Fimmel.

Would you consider this a “conspiracy theory” film?

My major point in this movie was to cause the viewer to question what he sees in mainstream media. I don’t have any more answers than anybody else does. But there are millions of people worldwide who buy into a good portion, if not all, of what in this movie was held up as absolute truth. So those people to me were not being represented in feature films. I didn’t make this film as a political statement. I realize that people would see it as that, and label it as a conspiracy-oriented film or a politically-oriented film. But I was very careful, while writing it, to not take that simple point of view. I didn’t want it to be preachy. What I wanted was to just try and give some indication that there are power structures in place in the world that do exist, and hold a great deal of influence over financial markets, political parties and governments around the world. Anybody who doubts that in this day and age is just living in a dream world. Does it go as far as I said it does? I don’t know. You decide.

My major point in this movie was to cause the viewer to question what he sees in mainstream media. I don’t have any more answers than anybody else does. But there are millions of people worldwide who buy into a good portion, if not all, of what in this movie was held up as absolute truth. So those people to me were not being represented in feature films. I didn’t make this film as a political statement. I realize that people would see it as that, and label it as a conspiracy-oriented film or a politically-oriented film. But I was very careful, while writing it, to not take that simple point of view. I didn’t want it to be preachy. What I wanted was to just try and give some indication that there are power structures in place in the world that do exist, and hold a great deal of influence over financial markets, political parties and governments around the world. Anybody who doubts that in this day and age is just living in a dream world. Does it go as far as I said it does? I don’t know. You decide.

Is Michael Desante’s “Terrorist” supposed to be Osama Bin Laden?

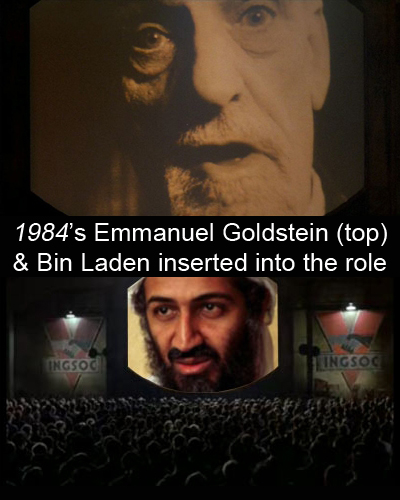

Many people don’t believe that Bin Laden is dead, based on all the nonsense that came up with the dumping of the body at sea, and the death of the Navy Seals that were involved in the operation two weeks later. There are many people who believe the whole thing was a political tool, which was wheeled out on time to further an agenda. But it came at a very convenient time for me, because it gave me an end for the movie. Anyway, the reason I didn’t want to name him “Osama Bin Laden” is because it specifies it too much. I wanted this guy to encapsulate the idea of an Islamic terrorist in the mind of the viewer. It wasn’t about Osama Bin Laden. I mean, we don’t know anything about him as it is. Bin Laden to me was always a fictional character. We only know what was being churned out about him in the press. We don’t know about him personally, or what he thought about things. It’s been a constant barrage of using this guy as a boogie man, in much the same way as Emmanuel Goldstein played that

Many people don’t believe that Bin Laden is dead, based on all the nonsense that came up with the dumping of the body at sea, and the death of the Navy Seals that were involved in the operation two weeks later. There are many people who believe the whole thing was a political tool, which was wheeled out on time to further an agenda. But it came at a very convenient time for me, because it gave me an end for the movie. Anyway, the reason I didn’t want to name him “Osama Bin Laden” is because it specifies it too much. I wanted this guy to encapsulate the idea of an Islamic terrorist in the mind of the viewer. It wasn’t about Osama Bin Laden. I mean, we don’t know anything about him as it is. Bin Laden to me was always a fictional character. We only know what was being churned out about him in the press. We don’t know about him personally, or what he thought about things. It’s been a constant barrage of using this guy as a boogie man, in much the same way as Emmanuel Goldstein played that  role in 1984. And I saw it very much as that. The fact that the guy, per say, didn’t exist at all. He was just a tool to put forward a certain agenda, which was the “War on Terror.” So that interested me. I used a lot of the stuff in Bin Laden’s background as the background story for the terrorist in the movie. Because I wanted to constantly play with this idea of ‘fact” and “fiction,” and where those two overlap. I wanted you always to be guessing, “Is this supposed to be Osama Bin Laden?” Well, there’s a certain point in the movie where it comes to 9/11, and you pretty much know that the character was based around Bin Laden — but not the Bin Laden that we’ve come to know from the media. It was a completely different guy. My point there was that because his background resembled in many cases what’s been reported about Bin Laden, that it would make it all the more chilling to see a very cultured, educated person claiming that the character that was being portrayed in his name was just a character. And that he was essentially just an actor playing a role that had been assigned to him for reasons of globally-motivated people who always need an enemy to fuel their agendas.

role in 1984. And I saw it very much as that. The fact that the guy, per say, didn’t exist at all. He was just a tool to put forward a certain agenda, which was the “War on Terror.” So that interested me. I used a lot of the stuff in Bin Laden’s background as the background story for the terrorist in the movie. Because I wanted to constantly play with this idea of ‘fact” and “fiction,” and where those two overlap. I wanted you always to be guessing, “Is this supposed to be Osama Bin Laden?” Well, there’s a certain point in the movie where it comes to 9/11, and you pretty much know that the character was based around Bin Laden — but not the Bin Laden that we’ve come to know from the media. It was a completely different guy. My point there was that because his background resembled in many cases what’s been reported about Bin Laden, that it would make it all the more chilling to see a very cultured, educated person claiming that the character that was being portrayed in his name was just a character. And that he was essentially just an actor playing a role that had been assigned to him for reasons of globally-motivated people who always need an enemy to fuel their agendas.

How did you go about constructing the set?

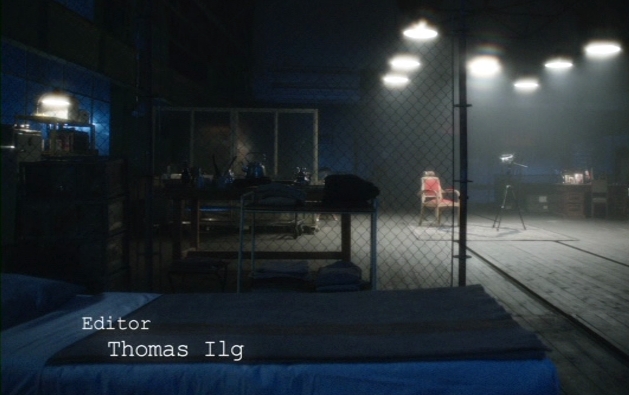

We constructed the set inside of an old iron factory outside of Vienna. And we had to build a platform, because the first floor of this iron factory looked too much like a factory. The second floor had these great windows. This building was World War II era, if not before, which is what we were looking for. So what we had to do is build a whole platform on the second story of this factory to utilize the location. And we looked at 3 or 4 places, but all of them had some problem attached. I mean, there was this great brewery called the Ottakringer Brewery. In the opening of the film, we actually used some of the sub-basement tunnels from it. But there was a rave going on there every weekend, where they were getting 1000-some people spending 30 Euros to go in. I mean, they were probably making around $100,000 a weekend in doing these elaborate parties. And there’s no way that we’re gonna set up everything to shoot the film, then break everything down for the weekend, just so that

We constructed the set inside of an old iron factory outside of Vienna. And we had to build a platform, because the first floor of this iron factory looked too much like a factory. The second floor had these great windows. This building was World War II era, if not before, which is what we were looking for. So what we had to do is build a whole platform on the second story of this factory to utilize the location. And we looked at 3 or 4 places, but all of them had some problem attached. I mean, there was this great brewery called the Ottakringer Brewery. In the opening of the film, we actually used some of the sub-basement tunnels from it. But there was a rave going on there every weekend, where they were getting 1000-some people spending 30 Euros to go in. I mean, they were probably making around $100,000 a weekend in doing these elaborate parties. And there’s no way that we’re gonna set up everything to shoot the film, then break everything down for the weekend, just so that  they could go in. So, we kept running into problems like this. We looked at a castle, which was really interesting. But I was looking for something kind of industrial that would provide this old train station underneath Vienna, and a castle just didn’t have that feeling. It was a beautiful space, but there was no way that I could re-write it that much. So we ended up finding this place, and at that point we had about a month to put that together. Thomas Feldkircher had to bring in heavy construction crews to build this whole platform. Then we had to extend it, because we weren’t getting enough distance on the cameras. And then we had to reinforce it, because we were talking for a while about using some crane shots, which we ended up not using. I would have loved to have done some really nice overheads, and some really nice tracking shots for establishing. But we just didn’t have the time. We were going through between 8-12 pages of dialogue per day, and we had 14 days to complete the movie. There were a couple of other locations created within the same complex. There was an

they could go in. So, we kept running into problems like this. We looked at a castle, which was really interesting. But I was looking for something kind of industrial that would provide this old train station underneath Vienna, and a castle just didn’t have that feeling. It was a beautiful space, but there was no way that I could re-write it that much. So we ended up finding this place, and at that point we had about a month to put that together. Thomas Feldkircher had to bring in heavy construction crews to build this whole platform. Then we had to extend it, because we weren’t getting enough distance on the cameras. And then we had to reinforce it, because we were talking for a while about using some crane shots, which we ended up not using. I would have loved to have done some really nice overheads, and some really nice tracking shots for establishing. But we just didn’t have the time. We were going through between 8-12 pages of dialogue per day, and we had 14 days to complete the movie. There were a couple of other locations created within the same complex. There was an  apartment in Afghanistan, and there were shots I called “black box” shots, which were memories of his childhood. I tried to figure out the easiest way to do that. If we tried to dress a room like a kid’s bedroom in America, it was not gonna look authentic. But when you remember something, the detail of a room isn’t something you remember. You remember what happened. So I just blanked out all of the detail, and put a bed, and created black partitions all around it, and then shot it that way. That solved a lot of problems. It was much cheaper to do, and we could accomplish shots much quicker. So those are the kinds of things that you have to creatively do on the fly when you’re faced with these challenges. We somehow pulled it off, but it was pretty tense there for a while.

apartment in Afghanistan, and there were shots I called “black box” shots, which were memories of his childhood. I tried to figure out the easiest way to do that. If we tried to dress a room like a kid’s bedroom in America, it was not gonna look authentic. But when you remember something, the detail of a room isn’t something you remember. You remember what happened. So I just blanked out all of the detail, and put a bed, and created black partitions all around it, and then shot it that way. That solved a lot of problems. It was much cheaper to do, and we could accomplish shots much quicker. So those are the kinds of things that you have to creatively do on the fly when you’re faced with these challenges. We somehow pulled it off, but it was pretty tense there for a while.

What was your approach to sourcing news footage?

I wanted to use real news archive documentary footage. The idea was that it would provide a certain familiarity. It would also indict the media with it’s own material. I wanted to do the same thing they do. Just take the information, spin it back the other way, and then offer you in many cases their confirming reports of everything that had been said. The thing was, news is no longer considered a public service within the United States. It is considered entertainment. News footage is sold the same way, and news networks will absolutely not license footage with their correspondents in it. That says it all to me, right there. News is no longer “news.” It’s entertainment that is sold as entertainment footage. So you can’t get Dan Rather reporting from Afghanistan. They won’t give it to you. You can’t get Peter Jennings saying, “This looks like a controlled demolition” when the Twin Towers are coming down. You can’t get all of those incredible things that would have made the news footage in this film so much more powerful. They will, in some cases, license you the footage with the text of what the reporter said. But you have to hire an actor to do a newscaster’s voice.

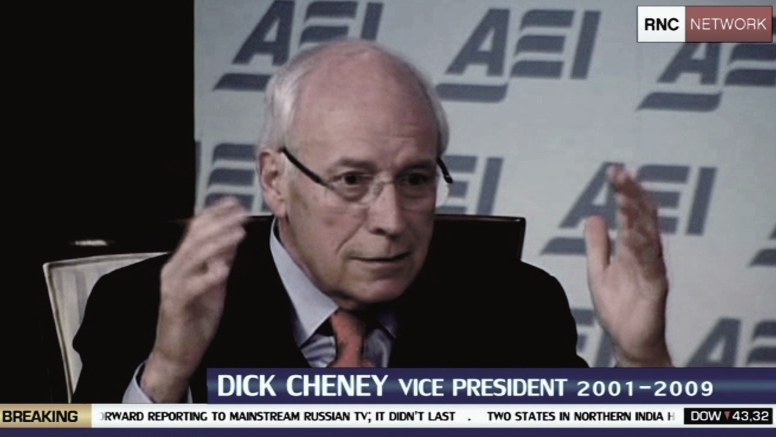

I wanted to use real news archive documentary footage. The idea was that it would provide a certain familiarity. It would also indict the media with it’s own material. I wanted to do the same thing they do. Just take the information, spin it back the other way, and then offer you in many cases their confirming reports of everything that had been said. The thing was, news is no longer considered a public service within the United States. It is considered entertainment. News footage is sold the same way, and news networks will absolutely not license footage with their correspondents in it. That says it all to me, right there. News is no longer “news.” It’s entertainment that is sold as entertainment footage. So you can’t get Dan Rather reporting from Afghanistan. They won’t give it to you. You can’t get Peter Jennings saying, “This looks like a controlled demolition” when the Twin Towers are coming down. You can’t get all of those incredible things that would have made the news footage in this film so much more powerful. They will, in some cases, license you the footage with the text of what the reporter said. But you have to hire an actor to do a newscaster’s voice.  So what I wanted to do with the news footage was illustrate how we experience mainstream news in this country, and how things are reported to us. But in many cases, we had to settle for scenes, rather than reports. We got some stuff from C-Span, and Dick Cheney on a program talking about the need for torture, basically. We took the Transportation Secretary, Norman Mineta, who heard Cheney give the stand-down order in the White House when planes were scrambled to shoot down airliners that were “heading toward” the Pentagon. Cheney issued the stand-down order, and Mineta re-tells that story. All of these things are good, but it would have been much more powerful footage if we could have used the real network and cable news network footage of what was happening that day. It would have added a whole other level to it. But they just refused to license it. So as it is now, we use more than 700 individual clips of footage from various places. But the cuts happen so quickly, that you’re not really conscious of how much time is being spent on them. You’re more hooked into the ongoing narrative and live action, and the footage is taking you out of that room and balancing it out.

So what I wanted to do with the news footage was illustrate how we experience mainstream news in this country, and how things are reported to us. But in many cases, we had to settle for scenes, rather than reports. We got some stuff from C-Span, and Dick Cheney on a program talking about the need for torture, basically. We took the Transportation Secretary, Norman Mineta, who heard Cheney give the stand-down order in the White House when planes were scrambled to shoot down airliners that were “heading toward” the Pentagon. Cheney issued the stand-down order, and Mineta re-tells that story. All of these things are good, but it would have been much more powerful footage if we could have used the real network and cable news network footage of what was happening that day. It would have added a whole other level to it. But they just refused to license it. So as it is now, we use more than 700 individual clips of footage from various places. But the cuts happen so quickly, that you’re not really conscious of how much time is being spent on them. You’re more hooked into the ongoing narrative and live action, and the footage is taking you out of that room and balancing it out.

We needed archiving first, and that was a major job that had to be orchestrated by Thomas Ilg, who ended up editing the movie. He created this system for archiving and labeling every piece of footage we had gotten. And we were using 2-3 different archives, like the AP, Thought Equity Motion, and a few other isolated archive sites. So the first big job was categorizing. Thomas would download maybe six different clips for one thing I had written. Because I had told him, “Look, just be creative. This is what I’m looking for. But if you find something that’s better, please just do it.” So it’s a cooperative thing. I was counting on his creativity too, and he actually turned out to be great. So that was the first job, and it started when I got there a month before production started. So he moved into this apartment with me, with all of this equipment. So I was looking at the stuff that he’s got, and I’ve got costume people coming over to show me things. And this is all going on simultaneously. I was looking at maybe 6-7 different clips, and selecting the one that I wanted for that part, or maybe having him put 2-3 of them together in a sequence. And Ivana, Travis and Peter Fonda were all pushing me to get a really well known

We needed archiving first, and that was a major job that had to be orchestrated by Thomas Ilg, who ended up editing the movie. He created this system for archiving and labeling every piece of footage we had gotten. And we were using 2-3 different archives, like the AP, Thought Equity Motion, and a few other isolated archive sites. So the first big job was categorizing. Thomas would download maybe six different clips for one thing I had written. Because I had told him, “Look, just be creative. This is what I’m looking for. But if you find something that’s better, please just do it.” So it’s a cooperative thing. I was counting on his creativity too, and he actually turned out to be great. So that was the first job, and it started when I got there a month before production started. So he moved into this apartment with me, with all of this equipment. So I was looking at the stuff that he’s got, and I’ve got costume people coming over to show me things. And this is all going on simultaneously. I was looking at maybe 6-7 different clips, and selecting the one that I wanted for that part, or maybe having him put 2-3 of them together in a sequence. And Ivana, Travis and Peter Fonda were all pushing me to get a really well known  editor from Hollywood to do it. But these guys are very expensive. We were looking at probably another $100,000 to bring an editor on board. But it occurred to me that this is not a usual film. It’s not like you’re just giving him the stuff that you shoot, and then letting him organize it according to the script. There’s a certain visceral relationship between the news footage, the live action, and the way you’re cutting in and out. Without a working knowledge of all the footage that was there, it was gonna be almost impossible for an editor — I don’t care who he is — to sit down with that kind of labyrinthine job. You have to first go through all of the footage that’s been assembled, and somehow creatively match that up with the cuts written into the script, and the stuff that we’d actually shot, while selecting pieces of the best performances. I mean, it’s a very, very elaborate process. And I realized that the only way we could ever get it done in a reasonable amount of time was to use Thomas Ilg to edit the movie. He actually turned out to be a very good editor. And some of the best compliments that we’ve received on this movie have been about the editing.

editor from Hollywood to do it. But these guys are very expensive. We were looking at probably another $100,000 to bring an editor on board. But it occurred to me that this is not a usual film. It’s not like you’re just giving him the stuff that you shoot, and then letting him organize it according to the script. There’s a certain visceral relationship between the news footage, the live action, and the way you’re cutting in and out. Without a working knowledge of all the footage that was there, it was gonna be almost impossible for an editor — I don’t care who he is — to sit down with that kind of labyrinthine job. You have to first go through all of the footage that’s been assembled, and somehow creatively match that up with the cuts written into the script, and the stuff that we’d actually shot, while selecting pieces of the best performances. I mean, it’s a very, very elaborate process. And I realized that the only way we could ever get it done in a reasonable amount of time was to use Thomas Ilg to edit the movie. He actually turned out to be a very good editor. And some of the best compliments that we’ve received on this movie have been about the editing.

What was the first screenplay you sold in the mid-’90’s about?

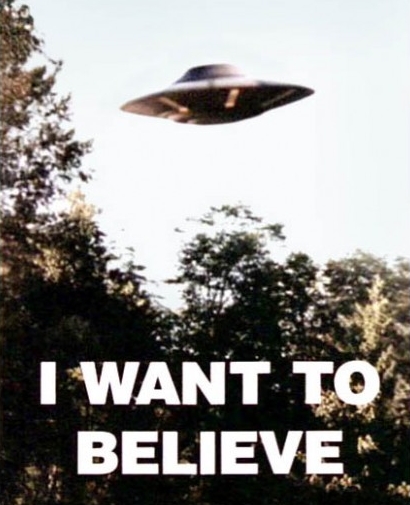

It was called Dreamland. Back in the days before The X-Files was a TV series, the UFO community was still considered this weird group of people in Iowa and Nebraska, who were living in trailer parks and seeing UFOs. But there had been a number of “credible researchers” who had done work into the project, like the MJ12 [or Majestic 12] documents. I could see this was a coming thing, and I knew people were gonna be captivated by it. So I hooked up with a well-known UFO researcher at the time, John Lear in Las Vegas. He was the son of the guy that invented the Learjet, and worked for the CIA as a pilot during Iran Contra. He was pretty interesting, and very, very strange. But he had file drawers full of classified documents that pertained to the UFO question, dating back to Project Blue Book, and well before it. I wasn’t really interested in writing a movie about aliens. I was interested in writing a script about people who are suddenly put into the middle of a completely new experience, and how they react to that. And so Dreamland was about the American government covering up the existence of extraterrestrials, at least since 1947. It may still be the best screenplay I ever wrote. When Michael Grais and Mark Victor found it, they were looking for precisely this kind of material. They’d read God-knows-how-many things about flying saucers. But when they ran across mine, I didn’t have an agent then. I didn’t know anybody. I’d just written a script.

It was called Dreamland. Back in the days before The X-Files was a TV series, the UFO community was still considered this weird group of people in Iowa and Nebraska, who were living in trailer parks and seeing UFOs. But there had been a number of “credible researchers” who had done work into the project, like the MJ12 [or Majestic 12] documents. I could see this was a coming thing, and I knew people were gonna be captivated by it. So I hooked up with a well-known UFO researcher at the time, John Lear in Las Vegas. He was the son of the guy that invented the Learjet, and worked for the CIA as a pilot during Iran Contra. He was pretty interesting, and very, very strange. But he had file drawers full of classified documents that pertained to the UFO question, dating back to Project Blue Book, and well before it. I wasn’t really interested in writing a movie about aliens. I was interested in writing a script about people who are suddenly put into the middle of a completely new experience, and how they react to that. And so Dreamland was about the American government covering up the existence of extraterrestrials, at least since 1947. It may still be the best screenplay I ever wrote. When Michael Grais and Mark Victor found it, they were looking for precisely this kind of material. They’d read God-knows-how-many things about flying saucers. But when they ran across mine, I didn’t have an agent then. I didn’t know anybody. I’d just written a script.  Some friends of mine ran this kind of alternative TV entity in West Hollywood. They were called EZTV, and they were like performance artists who did a lot of film stuff. A lot of actors and producers would go into their place on Santa Monica Boulevard, and they would cut their reels and other stuff. The way I found them was at a big art expo in L.A. I ran across their booth, and they had this film playing. The girl in it, Kim McKillip, is one of the founders of EZTV, and she played a victim of alien abduction. I thought, “Wow, that’s cool.” So I ended up talking to them, and getting to know them. I was working on the script at that time, and didn’t know what to do with it. So I gave it to those guys to read, thinking that at least they knew about the subject. And they got back to me and said, “This is great. Do you mind if we show this to somebody?” I said, “Show it to anybody you want. What have I got to lose?” Well, a few weeks later, I got a call from one of the producers of Unsolved Mysteries, who was a friend of these people, and who had read the script. He said, “I read the script about a week ago. I’ve passed it around to 2 or 3 people, who’ve also read it.

Some friends of mine ran this kind of alternative TV entity in West Hollywood. They were called EZTV, and they were like performance artists who did a lot of film stuff. A lot of actors and producers would go into their place on Santa Monica Boulevard, and they would cut their reels and other stuff. The way I found them was at a big art expo in L.A. I ran across their booth, and they had this film playing. The girl in it, Kim McKillip, is one of the founders of EZTV, and she played a victim of alien abduction. I thought, “Wow, that’s cool.” So I ended up talking to them, and getting to know them. I was working on the script at that time, and didn’t know what to do with it. So I gave it to those guys to read, thinking that at least they knew about the subject. And they got back to me and said, “This is great. Do you mind if we show this to somebody?” I said, “Show it to anybody you want. What have I got to lose?” Well, a few weeks later, I got a call from one of the producers of Unsolved Mysteries, who was a friend of these people, and who had read the script. He said, “I read the script about a week ago. I’ve passed it around to 2 or 3 people, who’ve also read it.  Everybody thinks it’s phenomenal. I hope you don’t mind, but we passed it along to big writer/producers who are looking for this kind of material.” Well, they just completely hit me out of left field. I was broke, and staying with some girl in Hollywood. The next day I got a call from them, saying they’d like to take me to lunch and talk about optioning my script. I remember we met at the Daily Grill. I think I had the first decent meal I’d had in two weeks. They said, “Look, we’ll option the script from you. We’ll give you $15,000 for that option. But you have to keep re-writing it until we’re satisfied with it.” So I said, “What’s wrong?” They said, “Nothing’s wrong. You have a really visual mind, which is great. The thing is, you’ve got too much good stuff. And in feature films, especially in Hollywood, you get one idea. You have to make your case for that one idea. In this script, you have 4 or 5 ideas that are great, but they’re going off in different directions.” I said, “OK, let’s do it.” And they really put me through a grinder for about six

Everybody thinks it’s phenomenal. I hope you don’t mind, but we passed it along to big writer/producers who are looking for this kind of material.” Well, they just completely hit me out of left field. I was broke, and staying with some girl in Hollywood. The next day I got a call from them, saying they’d like to take me to lunch and talk about optioning my script. I remember we met at the Daily Grill. I think I had the first decent meal I’d had in two weeks. They said, “Look, we’ll option the script from you. We’ll give you $15,000 for that option. But you have to keep re-writing it until we’re satisfied with it.” So I said, “What’s wrong?” They said, “Nothing’s wrong. You have a really visual mind, which is great. The thing is, you’ve got too much good stuff. And in feature films, especially in Hollywood, you get one idea. You have to make your case for that one idea. In this script, you have 4 or 5 ideas that are great, but they’re going off in different directions.” I said, “OK, let’s do it.” And they really put me through a grinder for about six  months, writing, re-writing, re-writing, getting more notes, re-writing again, more notes, re-writing. This was going on weekly, until they had taught me how to write the formula for a big screen Hollywood movie. I had also learned the ways you can appear to be following that formula, but at the same time subvert it in a certain way. And I remember Akiva Goldsman, a great writer, had read that script. He was one of the producers on a project that I was called in for at one of the studios — Fox Horizon, I think. It was about turning one of Robert Silverberg’s short stories into a screenplay. They’d given this to I don’t know how many writers, and they still weren’t satisfied with it. To my knowledge, it’s never been made yet. But when you get called in for these projects, what you’re asked to do is provide a script that is an example of your writing to the producers. And so Akiva Goldsman came back and said, “I don’t know how you did it, but it works.” Now, it was always my idea that information is just as compelling as action — if not more so — provided it’s the right information, and it’s revealed at the right time. It can be visceral, just like action. Maybe more so, because it’s in the mind. And I used that idea in that screenplay. It’s this really elaborate story about this guy who is in complete freefall. He at one time worked for the Office of Naval Intelligence. Now that I think back, it’s the same axe I’ve been grinding in Harodim. Anyway, he believes he’s had a nervous breakdown and was fired. Now his old boss, who really likes him, feeds him cases from time to time from government workers who need private investigations. Meanwhile, he’s developed a gambling problem, he’s lost his family, he’s living in Las Vegas — which, of course, is right near Area 51. So, he’s approached by this woman

months, writing, re-writing, re-writing, getting more notes, re-writing again, more notes, re-writing. This was going on weekly, until they had taught me how to write the formula for a big screen Hollywood movie. I had also learned the ways you can appear to be following that formula, but at the same time subvert it in a certain way. And I remember Akiva Goldsman, a great writer, had read that script. He was one of the producers on a project that I was called in for at one of the studios — Fox Horizon, I think. It was about turning one of Robert Silverberg’s short stories into a screenplay. They’d given this to I don’t know how many writers, and they still weren’t satisfied with it. To my knowledge, it’s never been made yet. But when you get called in for these projects, what you’re asked to do is provide a script that is an example of your writing to the producers. And so Akiva Goldsman came back and said, “I don’t know how you did it, but it works.” Now, it was always my idea that information is just as compelling as action — if not more so — provided it’s the right information, and it’s revealed at the right time. It can be visceral, just like action. Maybe more so, because it’s in the mind. And I used that idea in that screenplay. It’s this really elaborate story about this guy who is in complete freefall. He at one time worked for the Office of Naval Intelligence. Now that I think back, it’s the same axe I’ve been grinding in Harodim. Anyway, he believes he’s had a nervous breakdown and was fired. Now his old boss, who really likes him, feeds him cases from time to time from government workers who need private investigations. Meanwhile, he’s developed a gambling problem, he’s lost his family, he’s living in Las Vegas — which, of course, is right near Area 51. So, he’s approached by this woman  who claims she was a physicist at his top secret base that was responsible for back-engineering UFOs. And of course, this sounds completely crazy to him. Then there’s this group, MJ12. An agent working for them has hidden a recovered flying saucer, but they don’t know where. The problem is, the agent was gonna go public, so he is mind-controlled to forget who he is. And so I set up an idea that this woman is that agent, and she’s been mind-controlled. She claims that she worked at Los Alamos, and her past has been erased. So she comes to this guy, and asks him to investigate, to prove that she is who she says she is. So you think the whole time that she’s the agent. Turns out, she is a special psychologist who’s been sent in to restore his memory. He’s the one that’s been mind-controlled, and was the agent all along. So the revelations happen while he’s investigating what he thinks is her past. He’s really investigating his own past. That was a very cool device in the screenplay, and really worked. Anyway, the screenplay got around, and it eventually got me a really dedicated agent from a smaller agency who had spent months trying to find me. He had been a reader for one of the producers who had received it. It had no cover page, so he had to go through all these records and find out who had written it. By that time, he had gotten

who claims she was a physicist at his top secret base that was responsible for back-engineering UFOs. And of course, this sounds completely crazy to him. Then there’s this group, MJ12. An agent working for them has hidden a recovered flying saucer, but they don’t know where. The problem is, the agent was gonna go public, so he is mind-controlled to forget who he is. And so I set up an idea that this woman is that agent, and she’s been mind-controlled. She claims that she worked at Los Alamos, and her past has been erased. So she comes to this guy, and asks him to investigate, to prove that she is who she says she is. So you think the whole time that she’s the agent. Turns out, she is a special psychologist who’s been sent in to restore his memory. He’s the one that’s been mind-controlled, and was the agent all along. So the revelations happen while he’s investigating what he thinks is her past. He’s really investigating his own past. That was a very cool device in the screenplay, and really worked. Anyway, the screenplay got around, and it eventually got me a really dedicated agent from a smaller agency who had spent months trying to find me. He had been a reader for one of the producers who had received it. It had no cover page, so he had to go through all these records and find out who had written it. By that time, he had gotten  a job at this agency, and they found me. They took out an ad in The Hollywood Reporter. A friend of mine called me up and said, “You’ve got to get The Hollywood Reporter. You won’t believe it.” And I did, and there was a half-

a job at this agency, and they found me. They took out an ad in The Hollywood Reporter. A friend of mine called me up and said, “You’ve got to get The Hollywood Reporter. You won’t believe it.” And I did, and there was a half-

page ad saying “Paul Finelli, where are you? Will the writer of Dreamland please call this number…” I went, “You’ve gotta be kidding me.” So I called, and within a month they ended up getting me my first studio deal — which was with Columbia. It was actually bid on by three studios. It was an adaptation of Philip K. Dick’s short story about these time travelers who go a week in the future, and discover they’re dead. So now they have to find out what happened, which has already happened for everyone else. They have to backtrack what they did while they were in the future, before they get pulled back to the past, and die in this re-entry explosion. It was one of those very strange Philip Dick-ian stories, and I pitched it to a number of studios. The first one that really went for it was Columbia. Lisa Hansen was there then. And shortly thereafter, Hollywood Pictures came in. I think TriStar wanted it too. But they’re tricky, these studios. They give you 24 hours to respond, or they pull the deal. My first screenplay, I was being offered well above Writer’s Guild minimum — I mean, like double Writer’s Guild minimum at that time. I was being offered something like $125,000, and Guild minimum then was barely maybe $70,000. I don’t even think it was that much. And Hollywood Pictures, who guaranteed me they wanted to make the movie — guaranteed it up and down — because they were owned by Disney, only offered $75,000. That’s all they could get. I mean, Disney was notorious for not paying writers. And I was naive then. I figured,  “Well, shit, if Columbia’s willing to pay so much more, then they must want to make it that much more.” And that really wasn’t true at all. Hollywood Pictures was actually the first one to make a bid, and then Columbia made a bid after that, because Hollywood Pictures had done it. I started realizing the studio politics was really not about making the movie at all. It was about taking something somebody else wanted, and locking it up. So that was my first sale to a major studio. Suddenly, I was getting $100,000-plus for writing a screenplay. And that was really low for Hollywood. You know, Hollywood is very seductive that way, because it’s so completely out of whack. The rest of the world, it’s unthinkable that you get those amounts. In Europe, they don’t have that kind of money to put into films, and they’re interested in making films that have some value. But live and learn. I went through that for a long time in L.A. I was getting jobs, and I was getting paid, but I wasn’t getting any movies made. It was very deflating. Because every time you enter into a deal, you feel that this is gonna be the one. You’ve found reliable producers, and they’re gonna fight for you, and they’re gonna fight for the stuff. And then they don’t. It’s always the same story. You get put in a room with these people,

“Well, shit, if Columbia’s willing to pay so much more, then they must want to make it that much more.” And that really wasn’t true at all. Hollywood Pictures was actually the first one to make a bid, and then Columbia made a bid after that, because Hollywood Pictures had done it. I started realizing the studio politics was really not about making the movie at all. It was about taking something somebody else wanted, and locking it up. So that was my first sale to a major studio. Suddenly, I was getting $100,000-plus for writing a screenplay. And that was really low for Hollywood. You know, Hollywood is very seductive that way, because it’s so completely out of whack. The rest of the world, it’s unthinkable that you get those amounts. In Europe, they don’t have that kind of money to put into films, and they’re interested in making films that have some value. But live and learn. I went through that for a long time in L.A. I was getting jobs, and I was getting paid, but I wasn’t getting any movies made. It was very deflating. Because every time you enter into a deal, you feel that this is gonna be the one. You’ve found reliable producers, and they’re gonna fight for you, and they’re gonna fight for the stuff. And then they don’t. It’s always the same story. You get put in a room with these people,  and they’re throwing you contradictory notes, and they have no knowledge that the two notes they just gave you are completely contradictory. And if you even voice an opinion that that might be the case, you might get the reputation of being hard to work with. So, they’ve got you coming and going. And what happens is they pay you good money, but it’s never enough to get free of them. You have to keep going back to the well. Especially with the certain lifestyle that you are forced to live in L.A. Well, nobody held a gun to my head. But you have to drive a nice car, have a nice apartment, and you have to dress well. All of these things are part and parcel of being perceived as a successful writer in L.A. If you’re not perceived as that, you don’t get hired. Some other joker does, who they perceive to be more successful than you. Or they try to use you for as little as they can possibly get away with, figuring that you need the money bad. So there’s a very weird system that’s set up there. That’s why most of the people I knew who started out as really committed actors or writers, got so fucked up in the long run. Drugs, alcohol, you name it. It’s very difficult to avoid the feeling that you’re not doing what you always wanted to do. You’ve taken this weird turn, and made some series of compromises that have made you a factory worker. You’re a well-paid factory worker, but you’re just another cog in the wheel that nobody really cares about. And people spend their whole lives and careers doing this.

and they’re throwing you contradictory notes, and they have no knowledge that the two notes they just gave you are completely contradictory. And if you even voice an opinion that that might be the case, you might get the reputation of being hard to work with. So, they’ve got you coming and going. And what happens is they pay you good money, but it’s never enough to get free of them. You have to keep going back to the well. Especially with the certain lifestyle that you are forced to live in L.A. Well, nobody held a gun to my head. But you have to drive a nice car, have a nice apartment, and you have to dress well. All of these things are part and parcel of being perceived as a successful writer in L.A. If you’re not perceived as that, you don’t get hired. Some other joker does, who they perceive to be more successful than you. Or they try to use you for as little as they can possibly get away with, figuring that you need the money bad. So there’s a very weird system that’s set up there. That’s why most of the people I knew who started out as really committed actors or writers, got so fucked up in the long run. Drugs, alcohol, you name it. It’s very difficult to avoid the feeling that you’re not doing what you always wanted to do. You’ve taken this weird turn, and made some series of compromises that have made you a factory worker. You’re a well-paid factory worker, but you’re just another cog in the wheel that nobody really cares about. And people spend their whole lives and careers doing this.

Did your agent try and convince you to write more commercially mainstream scripts?

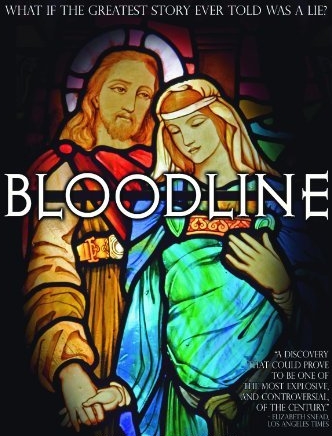

My agent said to me, “Paul, please, all you’ve gotta do is one.” Well, I’m actually incapable of writing on that level. I just can’t do it. I have no drive or inspiration for those kinds of movies. And I probably would have done it if I could of. But I just can’t. So, I avoided that trap. I mean, I took the meetings, and I heard all the incredibly moronic ideas that they had for films. But nothing was coming for me. I believed that I could do something that was geared for a more intelligent viewer, and still make it an entertainment movie. So I did a script called The Heresy, which was based on a non-fiction book called The Holy Blood and the Holy Grail. It was the first book that really dealt with the idea of Jesus having children, and that it had been kept a secret from the Middle Ages. Essentially, it said that Judaism and Christianity were the same religion, and that if you take all of the divinity away from Jesus, then something else had taken place — and it was a power thing. It was a great script, and I wrote it at least a year before Dan Brown released The Da Vinci Code, which essentially used all of the same background and was a massive bestseller. I did it for Original Films at TriStar. I got a call from my agent saying, “Original Films has more films slated for TriStar this year than anybody else. They’ve been given the commission by the head of the studio, Bob Cooper.” He was the guy who made HBO what it is by starting to make original series. He’s a really brilliant man. My agent said, “They want a Vatican thriller, and they asked if you had anything like that. I said, ‘No, but he could. It’s definitely something that he’d be interested in doing.’ So they said, ‘OK, send him in.'” So I went in, and I met their then-head of development, Stokely Chaffin. And I was

My agent said to me, “Paul, please, all you’ve gotta do is one.” Well, I’m actually incapable of writing on that level. I just can’t do it. I have no drive or inspiration for those kinds of movies. And I probably would have done it if I could of. But I just can’t. So, I avoided that trap. I mean, I took the meetings, and I heard all the incredibly moronic ideas that they had for films. But nothing was coming for me. I believed that I could do something that was geared for a more intelligent viewer, and still make it an entertainment movie. So I did a script called The Heresy, which was based on a non-fiction book called The Holy Blood and the Holy Grail. It was the first book that really dealt with the idea of Jesus having children, and that it had been kept a secret from the Middle Ages. Essentially, it said that Judaism and Christianity were the same religion, and that if you take all of the divinity away from Jesus, then something else had taken place — and it was a power thing. It was a great script, and I wrote it at least a year before Dan Brown released The Da Vinci Code, which essentially used all of the same background and was a massive bestseller. I did it for Original Films at TriStar. I got a call from my agent saying, “Original Films has more films slated for TriStar this year than anybody else. They’ve been given the commission by the head of the studio, Bob Cooper.” He was the guy who made HBO what it is by starting to make original series. He’s a really brilliant man. My agent said, “They want a Vatican thriller, and they asked if you had anything like that. I said, ‘No, but he could. It’s definitely something that he’d be interested in doing.’ So they said, ‘OK, send him in.'” So I went in, and I met their then-head of development, Stokely Chaffin. And I was  so fed up with these meetings at that point, that I wasn’t expecting that they were ever gonna go for it. So I said, “I understand that you want a Vatican thriller. First of all, we should put our cards on the table. I’m not interested in writing ‘Die Hard in the Vatican’. If I write something, it’s gonna be about faith and religion, and about real things.” She said, “What do you have in mind?” I said, “You sure you wanna hear this? Because I promise you that you’re never gonna get clearance to do this movie.” She said, “Well, tell me.” So I told her about The Holy Blood and the Holy Grail, and this idea that Jesus had had children with Mary Magdalene, and that the bloodline of Jesus had been kept secret throughout the Middle ages, and how the Templars were involved. She said, “This sounds phenomenal. We would love to do something like that.” And I thought, “Really?” So I spent the next three weeks putting together a very, very detailed treatment of this concept. It was about a young priest and medieval scholar investigating this stuff, who runs across evidence that this is happening. Meanwhile, people are getting killed. And if I say so myself, it was a very good script, and much better than Da Vinci Code. So now we’re scheduled to take the treatment in, and do the pitch to Bob Cooper, the head of the studio. But everybody’s freaking out, because Bob Cooper can only hear a pitch that is 15 minutes long. I had timed our pitch with Stokely 2 or 3 times, and we couldn’t get it any shorter than like 35 minutes. So I said, “Look, just leave it to me.” I walked into Cooper’s office and said, “I understand you can’t hear a pitch that’s longer than 15 minutes. But I can’t do that. So I’ll make you a deal. You can time me. And after 15 minutes, if you want me to stop,

so fed up with these meetings at that point, that I wasn’t expecting that they were ever gonna go for it. So I said, “I understand that you want a Vatican thriller. First of all, we should put our cards on the table. I’m not interested in writing ‘Die Hard in the Vatican’. If I write something, it’s gonna be about faith and religion, and about real things.” She said, “What do you have in mind?” I said, “You sure you wanna hear this? Because I promise you that you’re never gonna get clearance to do this movie.” She said, “Well, tell me.” So I told her about The Holy Blood and the Holy Grail, and this idea that Jesus had had children with Mary Magdalene, and that the bloodline of Jesus had been kept secret throughout the Middle ages, and how the Templars were involved. She said, “This sounds phenomenal. We would love to do something like that.” And I thought, “Really?” So I spent the next three weeks putting together a very, very detailed treatment of this concept. It was about a young priest and medieval scholar investigating this stuff, who runs across evidence that this is happening. Meanwhile, people are getting killed. And if I say so myself, it was a very good script, and much better than Da Vinci Code. So now we’re scheduled to take the treatment in, and do the pitch to Bob Cooper, the head of the studio. But everybody’s freaking out, because Bob Cooper can only hear a pitch that is 15 minutes long. I had timed our pitch with Stokely 2 or 3 times, and we couldn’t get it any shorter than like 35 minutes. So I said, “Look, just leave it to me.” I walked into Cooper’s office and said, “I understand you can’t hear a pitch that’s longer than 15 minutes. But I can’t do that. So I’ll make you a deal. You can time me. And after 15 minutes, if you want me to stop,  just hold up your hand and I’ll leave.” He said, “OK, that’s a fair enough deal.” So I did the pitch to him, and it took 45 minutes. The last 15 minutes, he actually had to go to the bathroom. But he wouldn’t get up, because didn’t want to interrupt the story. He heard it and said, “Amazing!” He immediately started talking to Neal Moritz about how to shoot it. “Do we do it in Rome?” Stokely and I walked out thinking we had the film made. And so, my agents wait to hear from the studio. A day goes by. Two days go by. We’re not hearing anything. I thought, “What the hell is going on. I mean, we had a deal when we walked out.” Third day goes by, and we get the news that Bob Cooper has quit as the head of TriStar. The most that I can piece together was that he actually went to them wanting make this movie. They said, “Are you crazy? We can’t deal with religion in Hollywood. It’s gonna turn everybody against us. The Jewish community’s gonna be up in arms, and so is the Christian community.” So he left, and ended up becoming head of Dreamworks about six months later. So I guess I can say that I had a hand in causing the resignation of probably one of the best heads of the studio that TriStar ever had — maybe the best.

just hold up your hand and I’ll leave.” He said, “OK, that’s a fair enough deal.” So I did the pitch to him, and it took 45 minutes. The last 15 minutes, he actually had to go to the bathroom. But he wouldn’t get up, because didn’t want to interrupt the story. He heard it and said, “Amazing!” He immediately started talking to Neal Moritz about how to shoot it. “Do we do it in Rome?” Stokely and I walked out thinking we had the film made. And so, my agents wait to hear from the studio. A day goes by. Two days go by. We’re not hearing anything. I thought, “What the hell is going on. I mean, we had a deal when we walked out.” Third day goes by, and we get the news that Bob Cooper has quit as the head of TriStar. The most that I can piece together was that he actually went to them wanting make this movie. They said, “Are you crazy? We can’t deal with religion in Hollywood. It’s gonna turn everybody against us. The Jewish community’s gonna be up in arms, and so is the Christian community.” So he left, and ended up becoming head of Dreamworks about six months later. So I guess I can say that I had a hand in causing the resignation of probably one of the best heads of the studio that TriStar ever had — maybe the best.

But this is the kind of stuff that happens in Hollywood. I was looking for something else, and I finally reached a point of being so frustrated and so dejected that I just didn’t want to be there anymore. And I had felt that way for a long time. This wasn’t something that occurred to me in one week, like “I’ve gotta get outta here.” It was a constant buildup to “If I stay here longer, I’m gonna kill myself.” And I was gonna die from who knows what — drugs, booze, something. I had to get out of there, so I ended up moving to Pittsburgh. [Finelli’s longtime girlfriend] Laura was here, and she’d had enough of L.A. too. She said, “Look, you’ve gotta get out of there. You’ve gotta get some reality in your life, and move to Pittsburgh.” So I thought that was the end, and that my film career was over. But what I discovered is that it liberated me. Because I started writing stuff that I would want to see, rather than what everybody was telling me they wanted to see. And the Harodim script came out of that.

How did you connect with producers of Harodim?