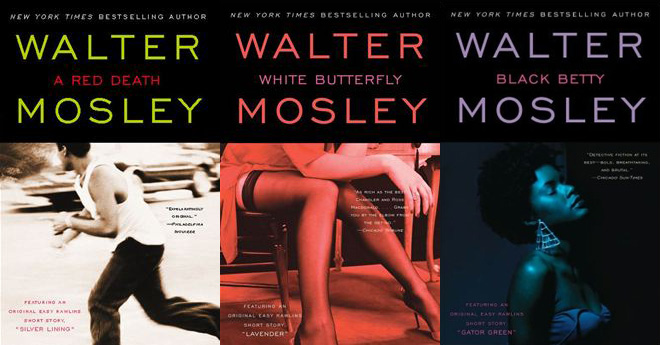

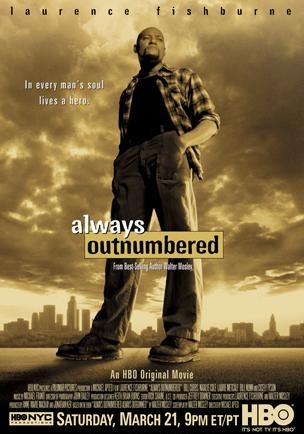

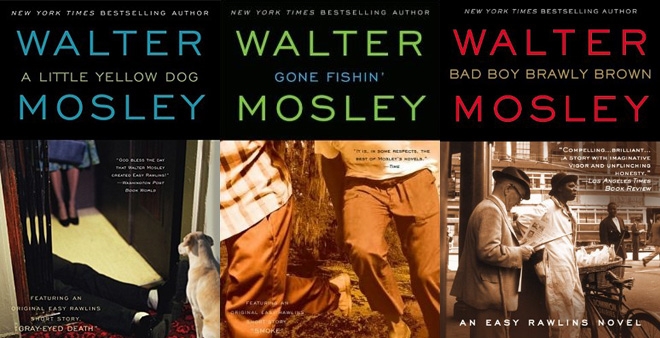

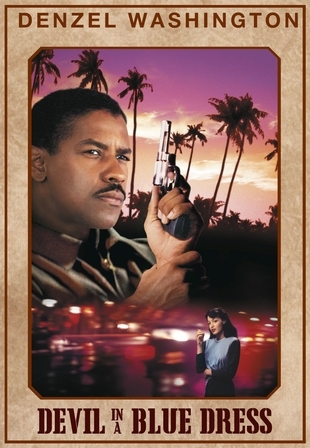

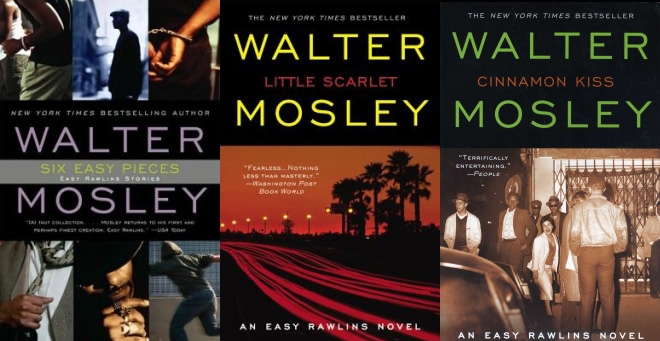

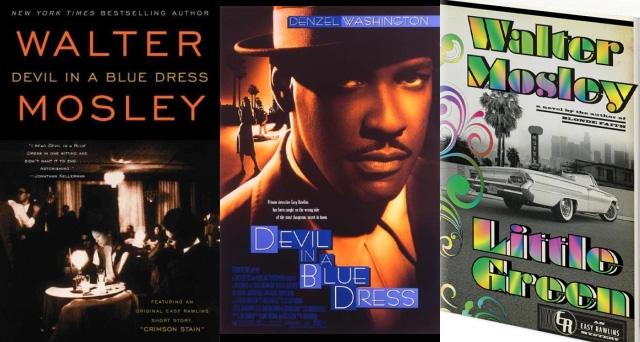

Who: Walter Mosley is a New York City-based author, whose 37+ book literary career goes back to 1990’s Devil in a Blue Dress. That novel kicked off a series revolving around detective Ezekiel “Easy” Rawlins — a Black resident of the Watts section of Los Angeles, whose continuing story begins in 1948, and (with the May 2013 release of his 12th story, Little Green by Knopf Doubleday) has now progressed to 1967. Mosley also wrote the character of ex-convict Socrates Fortlow, the modern-day hero of Always Outnumbered, Always Outgunned, and two other novels. Rawlins and Fortlow were adapted for the screen in the 1990s. Denzel Washington portrayed Rawlins in 1995’s Devil in a Blue Dress, directed by Carl Franklin. Laurence Fishburne portrayed Fortlow in 1998’s Always Outnumbered, directed by Michael Apted for HBO. During production Mosley met producer Diane Houslin, and in 2012 they partnered to launch a new production company: Best of Brooklyn Filmhouse. Other Mosley creations include Fearless Jones, portrayed by Bill Nunn in the final episode of Showtime’s anthology series, Fallen Angels. He has also authored several science-fiction stories — the latest being The Gift of Fire and On the Head of a Pin, which were released together in May 2012. Camera In The Sun interviewed Mosley in the summer of 2012, as he was editing Little Green, and discussed how his books have been adapted for the screen — including past and future versions of Easy Rawlins.

Who: Walter Mosley is a New York City-based author, whose 37+ book literary career goes back to 1990’s Devil in a Blue Dress. That novel kicked off a series revolving around detective Ezekiel “Easy” Rawlins — a Black resident of the Watts section of Los Angeles, whose continuing story begins in 1948, and (with the May 2013 release of his 12th story, Little Green by Knopf Doubleday) has now progressed to 1967. Mosley also wrote the character of ex-convict Socrates Fortlow, the modern-day hero of Always Outnumbered, Always Outgunned, and two other novels. Rawlins and Fortlow were adapted for the screen in the 1990s. Denzel Washington portrayed Rawlins in 1995’s Devil in a Blue Dress, directed by Carl Franklin. Laurence Fishburne portrayed Fortlow in 1998’s Always Outnumbered, directed by Michael Apted for HBO. During production Mosley met producer Diane Houslin, and in 2012 they partnered to launch a new production company: Best of Brooklyn Filmhouse. Other Mosley creations include Fearless Jones, portrayed by Bill Nunn in the final episode of Showtime’s anthology series, Fallen Angels. He has also authored several science-fiction stories — the latest being The Gift of Fire and On the Head of a Pin, which were released together in May 2012. Camera In The Sun interviewed Mosley in the summer of 2012, as he was editing Little Green, and discussed how his books have been adapted for the screen — including past and future versions of Easy Rawlins.

Why write another Rawlins mystery after what appeared to be his death in Blonde Faith?

Well, anybody who read that last book knows two things. Number one: You never saw his body. He went off a cliff. Number two: It’s a first-person narrative. And he says, “I blended into darkness,” or whatever. So the idea is maybe he didn’t die. But I didn’t want to be defined by Easy Rawlins. So I needed to do some other books. And since then, I’ve published between 15 and 20 books that are not Easy Rawlins, and I’m happy about that. I’m happy about doing the work. And also, it was getting stale. I’m editing the new book now, and really liking it, because it’s very different. He’s grown, and going through this near-death experience has really changed him. And so I’m able to talk about a new era in America, and also in his life. It wasn’t that I was always planning to get back to it, or not. It’s just that I had stopped for however long. The latest case is the Sunset Strip. Young Black man, who Mouse has some relationship to, goes up to the strip. He goes to the Strip, does some LSD — to be specific, Orange Speckled Barrel — with a young woman, and gets into trouble. And Easy first has to find him, then get him out of trouble. It takes place in 1967. And it was nice because I was a teenager then, so I kind of start remembering.

Well, anybody who read that last book knows two things. Number one: You never saw his body. He went off a cliff. Number two: It’s a first-person narrative. And he says, “I blended into darkness,” or whatever. So the idea is maybe he didn’t die. But I didn’t want to be defined by Easy Rawlins. So I needed to do some other books. And since then, I’ve published between 15 and 20 books that are not Easy Rawlins, and I’m happy about that. I’m happy about doing the work. And also, it was getting stale. I’m editing the new book now, and really liking it, because it’s very different. He’s grown, and going through this near-death experience has really changed him. And so I’m able to talk about a new era in America, and also in his life. It wasn’t that I was always planning to get back to it, or not. It’s just that I had stopped for however long. The latest case is the Sunset Strip. Young Black man, who Mouse has some relationship to, goes up to the strip. He goes to the Strip, does some LSD — to be specific, Orange Speckled Barrel — with a young woman, and gets into trouble. And Easy first has to find him, then get him out of trouble. It takes place in 1967. And it was nice because I was a teenager then, so I kind of start remembering.

How did you come to work with Diane Houslin on B.O.B., and John Wells on an Rawlins TV series?

I’ve known Diane for a long time. She’s one of the doc worker employees of HBO. And you know how they did those little films about the making of the movie? She was doing that for Always Outnumbered years ago, and I’ve known her since then. We’ve been friends, and she has all the talents that I don’t have about producing — who to talk to, how to talk to them, what things people like, what they don’t like. All the stuff that I just don’t know, and don’t pay any attention to. I’ve always wanted to work with her. And finally, three or four years ago, we got together and started working. Then we made the company, B.O.B. — Best Of Brooklyn. That’s been really good. Diane keeps me going. Because what happens with me is, I keep running off-track. Because I’m a novelist. I like writing novels. I write a lot of them. I’m also doing some plays, and working on a musical. I’m kind of all over the place. Right now, I think there are six different projects that we’re inching forward for television in Los Angeles. Plus, we’ve optioned my book The Last Days of Ptolemy Grey to Sam Jackson. Also, along with a writing partner, Cheo Hodari Coker, we’re writing a script for The Man in My Basement, which Anthony Mackie is very interested in. And the reason I’m able to do all those things is because Diane calls me and says, “Remember, you’re doing this.” And I go, “Oh, OK.”

I’ve known Diane for a long time. She’s one of the doc worker employees of HBO. And you know how they did those little films about the making of the movie? She was doing that for Always Outnumbered years ago, and I’ve known her since then. We’ve been friends, and she has all the talents that I don’t have about producing — who to talk to, how to talk to them, what things people like, what they don’t like. All the stuff that I just don’t know, and don’t pay any attention to. I’ve always wanted to work with her. And finally, three or four years ago, we got together and started working. Then we made the company, B.O.B. — Best Of Brooklyn. That’s been really good. Diane keeps me going. Because what happens with me is, I keep running off-track. Because I’m a novelist. I like writing novels. I write a lot of them. I’m also doing some plays, and working on a musical. I’m kind of all over the place. Right now, I think there are six different projects that we’re inching forward for television in Los Angeles. Plus, we’ve optioned my book The Last Days of Ptolemy Grey to Sam Jackson. Also, along with a writing partner, Cheo Hodari Coker, we’re writing a script for The Man in My Basement, which Anthony Mackie is very interested in. And the reason I’m able to do all those things is because Diane calls me and says, “Remember, you’re doing this.” And I go, “Oh, OK.”

John Wells, his group is a fun group to work with. So I tried to do a Fearless Jones series with him, which didn’t work. We wrote an Easy Rawlins series for NBC. They passed, but now we have it. So we’re gonna go to where we really should be with it — in cable. We’re thinking of going to A&E, Showtime, and that sounds good to me. What happened was, we wrote the script, and everybody at NBC loved it. They really did. I mean, I know because after they said “No”, they called me up to apologize. All of them. But we didn’t compromise, and they didn’t want to ask us to compromise. And so therefore, they didn’t do it, which is fine. I’m not unhappy with that. Working in television, people ask me “Are you excited?” I say, “No, I’m never excited until after the first season is over.” The Leonid McGill series, The Long Fall, we’ve been talking to some people I like — the producers of Justified, which I think is a great show — and a couple of other people. And then I’m working on developing another series with John Wells. You need a producer, and he’s really good, and his company’s really good. And a guy who’s optioned a graphic novel about the Blues came to Don Cheadle’s company, and I’ve come up with an idea for that series.

Why did you decide to get more involved in adapting your books with B.O.B. Filmhouse?

I would like to have something to do with it, because a lot of times — especially in feature film, but also in television — people get lost. Partially because they’re so frightened of getting fired, and not working, not getting their budget. And once you’ve been formed that way, it doesn’t matter how successful you get, you’re always frightened. You have two ways you can be: you can either be frightened, or be a bully. Those are the two ways. And so it’s good for me to be involved, and to be saying, “This is the character I wrote. This is what I want to do.” I can go talk to Laurence Fishburne, and I can go talk to other people like Anthony Mackie and say, “Look, I’d like to do this. I’d like to do it the way it is.” And have them respond, and say, “OK, yeah that’s what I want too.” I mean, it’s still gonna change. The people with the money are still gonna tell you what they’re willing to do, and what they’re not willing to do. But if I work with Diane, and with Mackie or Fishburne, or whoever else I’m working with — in the end, at least I feel that I’ve articulated what this series, or what this movie, or what this play or whatever can be. And so then I’m a part of the dialogue.

What was the process for adapting Always Outnumbered for HBO?

What was the process for adapting Always Outnumbered for HBO?

I was very involved in making that movie. I approached HBO, I approached Fishburne, and they both said “Yes” separately. HBO was doing movies then, and I’m actually doing another film with them, maybe — The Last Days of Ptolemy Grey with Sam Jackson. But then, they made a lot of movies, and that was really good. So you could go there, they gave you a good budget, they were very serious about the film. So you weren’t stuck on how many people were gonna buy tickets, and that kind of stuff. It was really nice. HBO said “Yes” before Laurence. And then I ran into him in New Orleans, and I asked him if he’d like to do it, and he said “Of course, let’s do it.”

HBO said, “Let’s just make the movie the way the book is. Because we like the book.” When you’re working on a Hollywood feature film, what happens is they see a book, and they just see a hook somewhere in it. And they say, “Well, how can we make your book fit around that hook?” That didn’t happen with HBO. They said, “We like this book. We wanna do it.” Same thing with Ptolemy Grey. They read it and said, “We wanna do this story.” And when HBO says that, I’m convinced they really wanna do the story.

I don’t think I wanted to write the script for Always Outnumbered. But Colin Callender, who was  running the film part of HBO at that time, said, “No, if you’re gonna do it with us, you’re gonna have to write it.” So I said, “All right.” It was fun. There’s the book where Socrates is in South Central, and he’s living among poor people. I remember bringing the script to the director, Michael Apted — who’s a wonderful director — him reading it, and giving me notes. So I was probably halfway or three-quarters through the script when he came and signed on. He said, “Let’s go all the way. Let’s do it the way it really looks. If you told me about this place, and I went there, that’s what it should look like.” And so he did, and it was great. Laurence was wonderful to work with, and it was really fun.

running the film part of HBO at that time, said, “No, if you’re gonna do it with us, you’re gonna have to write it.” So I said, “All right.” It was fun. There’s the book where Socrates is in South Central, and he’s living among poor people. I remember bringing the script to the director, Michael Apted — who’s a wonderful director — him reading it, and giving me notes. So I was probably halfway or three-quarters through the script when he came and signed on. He said, “Let’s go all the way. Let’s do it the way it really looks. If you told me about this place, and I went there, that’s what it should look like.” And so he did, and it was great. Laurence was wonderful to work with, and it was really fun.

I think Socrates is a real character, and an important character. You know, the problem that so-called minorities have in American culture of film, music and books is that they’re not, as a rule, portrayed as the people they are. Socrates is much more of a real character than pop culture can usually put its arms around. Right now, we’re developing a series for Laurence based on Socrates. He’s done some terrible things, and he’s trying to get better, but he doesn’t believe that he can really.

Did the period-L.A. setting of Devil in a Blue Dress significantly add to its budget?

Devil would be much easier to make now, because of CGI and stuff like that. I think it would have cost less money to make. It was like $20-million to get it in the can. Whereas we had $7-million for Always  Outnumbered. And I think you could probably make a movie that looks like Devil right now for maybe $10-million. And Always Outnumbered would cost you the same amount. You know, a budget matters, but it’s an ever-changing issue. What are the unions doing? What are actors costing? You could take any script, and take out explosions and car chases, and make it for a low budget. People don’t for a variety of reasons. But that’s an ever-changing question.

Outnumbered. And I think you could probably make a movie that looks like Devil right now for maybe $10-million. And Always Outnumbered would cost you the same amount. You know, a budget matters, but it’s an ever-changing issue. What are the unions doing? What are actors costing? You could take any script, and take out explosions and car chases, and make it for a low budget. People don’t for a variety of reasons. But that’s an ever-changing question.

Devil was a great movie, and it really showed Los Angeles at that time of transition in 1948. And Always Outnumbered I think was just beautiful. I love Always Outnumbered. Especially because it’s so much itself, that you really can’t compare it to another American movie. And I keep trying, but I can’t think of another movie that looks like it. Or even dramatically, a movie that arcs like it. On one hand, it’s really gritty and urban. And on the other hand, it’s very romantic.

One of the interesting things about L.A. for me is maybe 70% of the city looks just like it did back in the ’50s. Places have changed. I mean, Beverly Hills, Hollywood, Santa Monica — there are places that got very fancy. The urban parts. Not the residential parts. I went to an elementary school in Los  Angeles in the ’50s and ’60s. And I went back not long ago, and the school is still there. I mean, I never think about that with films. I was talking to Walter Bernstein, who wrote The Front, Fail-Safe and many other wonderful films. He’s 93 now, and he was talking to me about how in his 80s he had a meeting about a period film, and these 20 year-old producers came in and said, “Mr. Bernstein, let us explain to you how a screenplay works.” You know, they felt somebody was paying them money to act like they knew something, rather than learning something. So they said to him, “Oh, it’s a period piece, it’s gonna be very expensive.” Well, not if you’re smart it isn’t. It’s not gonna be that much more expensive. And so I don’t think about it. I know other people do. But I don’t think about it.

Angeles in the ’50s and ’60s. And I went back not long ago, and the school is still there. I mean, I never think about that with films. I was talking to Walter Bernstein, who wrote The Front, Fail-Safe and many other wonderful films. He’s 93 now, and he was talking to me about how in his 80s he had a meeting about a period film, and these 20 year-old producers came in and said, “Mr. Bernstein, let us explain to you how a screenplay works.” You know, they felt somebody was paying them money to act like they knew something, rather than learning something. So they said to him, “Oh, it’s a period piece, it’s gonna be very expensive.” Well, not if you’re smart it isn’t. It’s not gonna be that much more expensive. And so I don’t think about it. I know other people do. But I don’t think about it.

What was it like adapting Fearless Jones for Fallen Angels on Showtime?

The first Fearless story I wrote they made into an episode. It was just a short story introducing the character. That was fun. I wrote the short story, and gave it to them before it was published. It was one show. Bill Nunn was Fearless. Giancarlo Esposito was Paris Minton. It was wonderful. And that was period, and it worked fine. And Showtime doesn’t have gigantic budgets for these things. The story is really about the friendship between Paris and Fearless. And this woman gets involved, and they try to help her out — and they do, after a fashion. But the story is also about L.A. It’s about Black people in L.A. One of the things that’s so interesting to me is that you have this incredible city of Los Angeles that has a deep, deep, deep Chicano history. Some of the first inhabitants of old Los Angeles were Black people. And then you have Japanese, Korean, Chinese — all these people who have a deep and very important part of the history of Los Angeles, but don’t appear anywhere in the literature. And because they don’t appear in the literature, they don’t appear in movies, or they appear like caricatures.

The first Fearless story I wrote they made into an episode. It was just a short story introducing the character. That was fun. I wrote the short story, and gave it to them before it was published. It was one show. Bill Nunn was Fearless. Giancarlo Esposito was Paris Minton. It was wonderful. And that was period, and it worked fine. And Showtime doesn’t have gigantic budgets for these things. The story is really about the friendship between Paris and Fearless. And this woman gets involved, and they try to help her out — and they do, after a fashion. But the story is also about L.A. It’s about Black people in L.A. One of the things that’s so interesting to me is that you have this incredible city of Los Angeles that has a deep, deep, deep Chicano history. Some of the first inhabitants of old Los Angeles were Black people. And then you have Japanese, Korean, Chinese — all these people who have a deep and very important part of the history of Los Angeles, but don’t appear anywhere in the literature. And because they don’t appear in the literature, they don’t appear in movies, or they appear like caricatures.

Devil in a Blue Dress was a very good movie, and it was a very serious movie. It was entertaining, and it was fun, but the characters in it had lives of their own. And they weren’t lives where they were aping or mimicking some other culture. And I think it’s hard for people. They look at it and go, “Wow.” I remember going around on the tour for the book of Always Outnumbered. White male journalists would talk to me, and they would say, “I don’t know if I can forgive Socrates.” And I said, “Well, that’s OK, because he doesn’t care what you think.” And it was really funny. It was a pat answer. I usually don’t have pat answers, but I had that one. And they would go, “Wow.” And I think that’s it. The fact that when you run across a guy who isn’t beholden to you, that’s definitely in there.

What’s the role of race in Leonid McGill’s period-New York, compared to Fearless & Easy’s L.A.?

Leonid McGill in 1950 would be treated very similar to Easy in 1950. New York, L.A., it makes no difference. You have the same treatment. There was a little less segregation in L.A. at that time. But  the more integration you have, the more conflict you have. One thing that’s kind of strange is that the more the races blend together, the more conflict, worries, fears and paranoias you have. More or less, it would be the same. But what changes them differently is time. You know, there are places that you go that would be different. New Orleans would be a little different at any time. Hawaii would be a little different at any time. Alaska would be a little different at any time. But most of the major places, like New York, Chicago and Los Angeles — they’re really gauged by the era. So even if I was to write a contemporary L.A. detective, which I’ve never even thought of doing until this moment, he wouldn’t be much like Easy either. I know this, because I go to L.A. a lot to work on these shows, and I’m usually staying in Beverly Hills. And when I’m in Beverly Hills, I see Black people jogging, and on skateboards and bicycles, and interracial couples going up and down the street. When I was a kid, no, the police would stop every one of those people and say, “What are you doing here?” telling them, “You shouldn’t be here.”

the more integration you have, the more conflict you have. One thing that’s kind of strange is that the more the races blend together, the more conflict, worries, fears and paranoias you have. More or less, it would be the same. But what changes them differently is time. You know, there are places that you go that would be different. New Orleans would be a little different at any time. Hawaii would be a little different at any time. Alaska would be a little different at any time. But most of the major places, like New York, Chicago and Los Angeles — they’re really gauged by the era. So even if I was to write a contemporary L.A. detective, which I’ve never even thought of doing until this moment, he wouldn’t be much like Easy either. I know this, because I go to L.A. a lot to work on these shows, and I’m usually staying in Beverly Hills. And when I’m in Beverly Hills, I see Black people jogging, and on skateboards and bicycles, and interracial couples going up and down the street. When I was a kid, no, the police would stop every one of those people and say, “What are you doing here?” telling them, “You shouldn’t be here.”

In the four Leonid books, he’s been stopped by the police once for being Black and walking down the street. And Easy, it might happen 3 or 4 times in one book. He’d walk in the building, and they stop him.  He walks out of the building, and they stop him. He gets in the car, and they stop him. And then he kills somebody, and they don’t stop him. But you know, it’s like that. In Leonid’s New York, no, they’re not on him. And maybe in the ’50s and ’60s, maybe even less than in L.A., they would stop him. I mean, they would, but it would be less. Of course, Leonid is not the Black youth in the ‘hood in New York that are getting stopped and searched every day. I mean, it’s still happening, but Leonid is living in a different place. He’s also a different age. Racism in New York now also is tinged with agism. They’re worried that young people have guns. Well, Bloomberg is good about that. But instead of worrying about why they have the guns, they’re worried that they do have the guns. What? It’s like, you’re the ones who let guns loose on the streets of the city, and then you’re gonna get on people for having them? What’s wrong with you? But again, Leonid’s story is not a racial one. He’s a Black hero, and a Black male hero in America. But it’s not a racial concept. It’s a lot about class, which is why he has a Russian name — named by his anarchist father, who thought he was a communist.

He walks out of the building, and they stop him. He gets in the car, and they stop him. And then he kills somebody, and they don’t stop him. But you know, it’s like that. In Leonid’s New York, no, they’re not on him. And maybe in the ’50s and ’60s, maybe even less than in L.A., they would stop him. I mean, they would, but it would be less. Of course, Leonid is not the Black youth in the ‘hood in New York that are getting stopped and searched every day. I mean, it’s still happening, but Leonid is living in a different place. He’s also a different age. Racism in New York now also is tinged with agism. They’re worried that young people have guns. Well, Bloomberg is good about that. But instead of worrying about why they have the guns, they’re worried that they do have the guns. What? It’s like, you’re the ones who let guns loose on the streets of the city, and then you’re gonna get on people for having them? What’s wrong with you? But again, Leonid’s story is not a racial one. He’s a Black hero, and a Black male hero in America. But it’s not a racial concept. It’s a lot about class, which is why he has a Russian name — named by his anarchist father, who thought he was a communist.

There was always a little leeway with [Black people] owning property in Los Angeles. Much more so than in New York. I remember Harry Belafonte once told me that he wanted to rent an apartment in New York in the ’50’s. But he was married to a white woman,  so he couldn’t rent the apartment. But he could buy the building, and he did. Most people can’t do that. But he was the first million-album seller, so I guess he could. There was some leeway. And yes, there was a Black neighborhood in Devil. But Easy’s happy because he came from a place where Black people could own things, but those things could be taken away from you. You could own things, but you better not be doing too well at that thing. You could get a job, but most jobs were held for White people. And so the jobs you got, you didn’t get paid very well, and it wasn’t a very good job, and there was no upward mobility. And so to be able to have two or three jobs, to own your own property, to send your kids to a school where they really learn how to read — he was very happy about that.

so he couldn’t rent the apartment. But he could buy the building, and he did. Most people can’t do that. But he was the first million-album seller, so I guess he could. There was some leeway. And yes, there was a Black neighborhood in Devil. But Easy’s happy because he came from a place where Black people could own things, but those things could be taken away from you. You could own things, but you better not be doing too well at that thing. You could get a job, but most jobs were held for White people. And so the jobs you got, you didn’t get paid very well, and it wasn’t a very good job, and there was no upward mobility. And so to be able to have two or three jobs, to own your own property, to send your kids to a school where they really learn how to read — he was very happy about that.

A lot of people want to talk about “post-racial” for ridiculous reasons. We’re in no way in a post-racial country or a post-racial world. But there are other issues that are so powerful, so demanding, that  you really can’t call race the number one thing. So Leonid McGill is this detective who has the Swedish wife, but they don’t really love each other. They have three children, but two of them he didn’t father, but she says he did. I mean, it’s a whole complex world. And he’ll say, “Listen, I don’t have time to worry about race. I’ve got too many serious things on my mind. People are trying to kill me. And they’re not trying to kill me because I’m Black, you know.” But he’s a part of that world in a way that the world has changed. When I do my political talks, one of the things I often say to people is, “The older you are, the more you live in the past.” And I was listening to a woman talk the other day. She said, “You know, people under the age of 30, 50% of them have dated outside their race.” But the people who make the final decisions about what goes on television, they’re all over 30. And the people who are trying to satisfy those people have to think like them, even if they’re younger. And so you look at television, and if 3% of the people are interracial in any kind of way, it’s pretty amazing. So you have a world that’s represented that’s actually culturally a depiction of the past. No matter how much it’s in the present, and it seems like in the present, culturally the minds that are making these decisions are thinking of another time. And it’s hard for people to get over that. You know, young people are all good and well, but they are always selling themselves to older people. Are they gonna hire me? Are they gonna give me the job? So people who are trying to say things that are new, that’ll never work, because it wouldn’t work 20 years ago.

you really can’t call race the number one thing. So Leonid McGill is this detective who has the Swedish wife, but they don’t really love each other. They have three children, but two of them he didn’t father, but she says he did. I mean, it’s a whole complex world. And he’ll say, “Listen, I don’t have time to worry about race. I’ve got too many serious things on my mind. People are trying to kill me. And they’re not trying to kill me because I’m Black, you know.” But he’s a part of that world in a way that the world has changed. When I do my political talks, one of the things I often say to people is, “The older you are, the more you live in the past.” And I was listening to a woman talk the other day. She said, “You know, people under the age of 30, 50% of them have dated outside their race.” But the people who make the final decisions about what goes on television, they’re all over 30. And the people who are trying to satisfy those people have to think like them, even if they’re younger. And so you look at television, and if 3% of the people are interracial in any kind of way, it’s pretty amazing. So you have a world that’s represented that’s actually culturally a depiction of the past. No matter how much it’s in the present, and it seems like in the present, culturally the minds that are making these decisions are thinking of another time. And it’s hard for people to get over that. You know, young people are all good and well, but they are always selling themselves to older people. Are they gonna hire me? Are they gonna give me the job? So people who are trying to say things that are new, that’ll never work, because it wouldn’t work 20 years ago.

Which authors do you feel depict Los Angeles especially well in their work?

Los Angeles is really well-done in Chandler’s books, and also in the films of his books. They covered L.A. very well. The Long Goodbye is Chandler’s best book, I think. And I think later on, Ellroy does a  really good job, and the movies are really well done. I’m not unhappy about how L.A. is depicted as a rule, except for when it’s “White L.A.”, and so it’s a made-up L..A. It’s like these films where they say well, “L.A. was a White place.” Well, no, it wasn’t a White place. It never was a White place ever. And as it grew, it grew evenly among the cultures. So you see these wonderful films, and you get a great feeling for L.A. Like Chinatown, which is just gorgeous. You get a feeling for the place that’s wonderful, but it’s not accurate. You just kind of feel bad about that. Like, “Come on now. This was never true.”

really good job, and the movies are really well done. I’m not unhappy about how L.A. is depicted as a rule, except for when it’s “White L.A.”, and so it’s a made-up L..A. It’s like these films where they say well, “L.A. was a White place.” Well, no, it wasn’t a White place. It never was a White place ever. And as it grew, it grew evenly among the cultures. So you see these wonderful films, and you get a great feeling for L.A. Like Chinatown, which is just gorgeous. You get a feeling for the place that’s wonderful, but it’s not accurate. You just kind of feel bad about that. Like, “Come on now. This was never true.”

So if you start to define Watts by just a certain aspect of it — like gang culture or youth culture — you completely misunderstand the notion. Like the gangs in South Central, it isn’t the Tongs. It changes from block to block to block. And even with that, you have a lot of people who live there, work there, libraries. There’s a whole range of life going on. I don’t mind it when you hone in on one person’s life, and there’s something specific there. But the world around should represent the entire world — people going to church, people being in restaurants, people going into business. You know, people having those crazy conversations they have in barber shops and stuff. Without a sense of reality, it becomes a caricature or a cartoon.

The first thing I always think of when someone says New York is the television series Kojak with Telly Savalas. Because I just thought they got New York, and they got it right. He went to every part of New York, and he had a New York attitude. It’s a little dated when you watch it now. But when you  watched it then, my God it really did well. Then movies like The Panic in Needle Park with Al Pacino, that was a really good movie. And I think there’s a desire in New York where New Yorkers want to tell the real story. People looking at films about New York want to see the real story. And when you have L.A., they want the Hollywood story. They want another story. I mean, every once in a while people like Ellroy actually do a thing which works. It’s tough and gritty Los Angeles. Listen, Ellroy’s a wonderful writer. And I like Ellroy, because I see us as counterparts. You know, like we’re at the opposite ends of the bookshelf. But we’re supporting all these things in between us. And the movie, L.A. Confidential is really very good. You know, it’s wild like Ellroy is wild. And that’s not me. I don’t think that way. It’s not that I’m domestic. It’s just that the wildness gets located in specific places, like Mouse. Mouse comes from the Fifth Ward of Houston, Texas, which is really tough. You know, Mouse could be the whole landscape of Ellroy’s books. And I like to leave in just one or two of those characters.

watched it then, my God it really did well. Then movies like The Panic in Needle Park with Al Pacino, that was a really good movie. And I think there’s a desire in New York where New Yorkers want to tell the real story. People looking at films about New York want to see the real story. And when you have L.A., they want the Hollywood story. They want another story. I mean, every once in a while people like Ellroy actually do a thing which works. It’s tough and gritty Los Angeles. Listen, Ellroy’s a wonderful writer. And I like Ellroy, because I see us as counterparts. You know, like we’re at the opposite ends of the bookshelf. But we’re supporting all these things in between us. And the movie, L.A. Confidential is really very good. You know, it’s wild like Ellroy is wild. And that’s not me. I don’t think that way. It’s not that I’m domestic. It’s just that the wildness gets located in specific places, like Mouse. Mouse comes from the Fifth Ward of Houston, Texas, which is really tough. You know, Mouse could be the whole landscape of Ellroy’s books. And I like to leave in just one or two of those characters.

What’s the plot of The Gift of Fire, and what appeals to you about writing science-fiction?

It’s a novella, because it’s 30,000 words. I wrote a series of six novellas, which Tor is publishing in three different volumes. And the only thing they have in common is that they’re either science-fiction  or fantasy. In each one, a Black man destroys the world. And it’s not necessarily a violent destruction, but the world as we know it. The structure of the world will no longer be the same. And in this one I just take a Mediterranean god, Prometheus, who finally escapes from his imprisonment and comes to Earth. He passes his power onto a quadriplegic Black kid, who takes on the mantle of Prometheus, giving the gift of “fire” — the gift of awareness. Prometheus gave the first fire, which is awareness. And now his protege is gonna give the next fire, which is self-awareness. That’s understanding yourself in relation to your society, which is a very political thing. But it doesn’t seem political when you’re reading it, because all these wild magical things are happening. It was lots of fun to write.

or fantasy. In each one, a Black man destroys the world. And it’s not necessarily a violent destruction, but the world as we know it. The structure of the world will no longer be the same. And in this one I just take a Mediterranean god, Prometheus, who finally escapes from his imprisonment and comes to Earth. He passes his power onto a quadriplegic Black kid, who takes on the mantle of Prometheus, giving the gift of “fire” — the gift of awareness. Prometheus gave the first fire, which is awareness. And now his protege is gonna give the next fire, which is self-awareness. That’s understanding yourself in relation to your society, which is a very political thing. But it doesn’t seem political when you’re reading it, because all these wild magical things are happening. It was lots of fun to write.

Science-fiction allows you to question reality. Because when you’re writing so-called non-fiction, you don’t question reality. So you can actually make stories in which New York only has White people in it, Brooklyn only has White people in it, Americans are all rich, democracy and capitalism are the same thing. You can make it, because it seems like that’s the world we’re asked to believe. Even though, if you looked at it from another way, you’d go, “Why? This  doesn’t make any sense.” When it comes to saying “Anyone can be rich,” well in science-fiction you can actually make a world in which everybody’s rich. So you have somebody like Ray Bradbury doing beautiful work. Let’s say you’re a radical lesbian feminist separatist. You can start your novel, “By the year 2023, there were no more men on the face of the earth.” And then you can begin to say, “Well, what’s that world like?”, and then look at it. So science-fiction allows you to look at just a specific kind of band, and then your understanding of the world that exists becomes much broader. Because you have questions.

doesn’t make any sense.” When it comes to saying “Anyone can be rich,” well in science-fiction you can actually make a world in which everybody’s rich. So you have somebody like Ray Bradbury doing beautiful work. Let’s say you’re a radical lesbian feminist separatist. You can start your novel, “By the year 2023, there were no more men on the face of the earth.” And then you can begin to say, “Well, what’s that world like?”, and then look at it. So science-fiction allows you to look at just a specific kind of band, and then your understanding of the world that exists becomes much broader. Because you have questions.

In another one, there’s a guy who figures out how to blend the minds of people. So you and I can actually share thoughts. So if I have a mental talent, but not the physical talent to do that thing, and you have the physical ability, but you don’t have the mental talent, then we can actually share our beliefs. In a couple of stories, Black men in this world make pacts with alien cultures, and invite them to come to Earth, even though that’s gonna make the Earth change completely. And in one of them, there’s a guy who seems kind of slow-witted, works in a mail room, he’s in his 40s. And it turns out that in a very specific way he is God. But he’s forgotten, because he’s wanted to live among his creations. And this is the character he came up with to live among them as.

What sorts of political writings do you plan to pursue?

I’m very interested in the idea of the convergence of capitalism and communism. I wrote about it in Futureland, another science-fiction book. It’s almost a joke, but I think it’s true that when you look at all the problems of the world, and you say “What does capitalism want?” — capitalism wants profit.  That’s all they want is profit. Nothing else really matters, except making money and competing to make money. What does communism want? Well, communism wants to end private property. So you could say, “Well, it seems like those two things could never get together.” But if you had a world in which everything was leased, you would have that. If you leased your car, your house, your shoes, your furniture, your television — everything, except for that stuff like food, stuff that wears out immediately — then you would have corporations that would own these things. They would be the only entities that could own these things, lease these things, and replace these things. And you would save the ecology, because you wouldn’t have planned obsolescence and destruction. And at the same time, you would have a world which would want to support people being able to live in a world where they could lease and continue on. It’s a very complex thing, with a lot of different levels to it. But I would like to start thinking about that. Because the idea of democracy, capitalism and communism all acting as if they’re different, and that they could live separately, or that one could defeat the other… When a man falls dead on the street, somebody has to come move that body, and there can be no profit in that. So obviously there has to be some socialism. You have to have water. You have to have subway trains. You have to have police. There’s no profit there. That’s social. It’s even socialistic. I don’t think I have the answer, but I think it’s important to think about how to have one.

That’s all they want is profit. Nothing else really matters, except making money and competing to make money. What does communism want? Well, communism wants to end private property. So you could say, “Well, it seems like those two things could never get together.” But if you had a world in which everything was leased, you would have that. If you leased your car, your house, your shoes, your furniture, your television — everything, except for that stuff like food, stuff that wears out immediately — then you would have corporations that would own these things. They would be the only entities that could own these things, lease these things, and replace these things. And you would save the ecology, because you wouldn’t have planned obsolescence and destruction. And at the same time, you would have a world which would want to support people being able to live in a world where they could lease and continue on. It’s a very complex thing, with a lot of different levels to it. But I would like to start thinking about that. Because the idea of democracy, capitalism and communism all acting as if they’re different, and that they could live separately, or that one could defeat the other… When a man falls dead on the street, somebody has to come move that body, and there can be no profit in that. So obviously there has to be some socialism. You have to have water. You have to have subway trains. You have to have police. There’s no profit there. That’s social. It’s even socialistic. I don’t think I have the answer, but I think it’s important to think about how to have one.

0 Comments