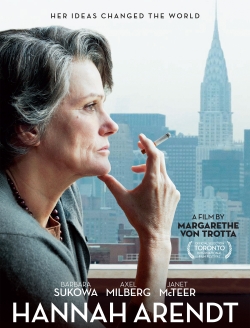

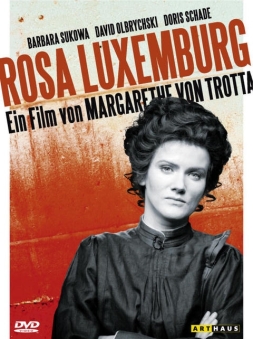

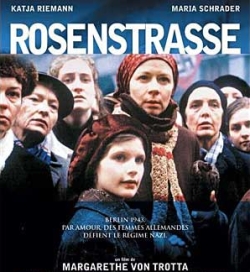

Who: Pamela Katz is a New York City-based screenwriter, whose latest script is for a biographical film about German-Jewish political philosopher Hannah Arendt — whose 1963 book, Eichmann in Jerusalem: A Report of the Banality of Evil was drawn from Arendt’s own reports for The New Yorker on Adolf Eichmann’s 1961 trial in Israel. That period of Arendt’s life is the center of the film, which stars Barbara Sukowa as Arendt and is directed by Margarethe Von Trotta — with whom Katz previously collaborated on the 2003 film Rosenstrasse, and the 2004 TV movie, The Other Woman (also starring Sukowa). Sukowa had previously embodied German-Jewish revolutionary Rosa Luxemburg in Von Trotta’s acclaimed 1986 film of the same name. Katz also wrote the 2011 film Remembrance, about a couple who manage to escape Auschwitz during World War II, only to be separated, and then reunite 30 years later. Camera In The Sun sat down with Katz as she promoted Arendt‘s run of screenings at Manhattan’s Film Forum in June 2013, and discussed its subject’s complicated personality, and continued influence on the way people think about a variety of subjects — especially the Holocaust.

Who: Pamela Katz is a New York City-based screenwriter, whose latest script is for a biographical film about German-Jewish political philosopher Hannah Arendt — whose 1963 book, Eichmann in Jerusalem: A Report of the Banality of Evil was drawn from Arendt’s own reports for The New Yorker on Adolf Eichmann’s 1961 trial in Israel. That period of Arendt’s life is the center of the film, which stars Barbara Sukowa as Arendt and is directed by Margarethe Von Trotta — with whom Katz previously collaborated on the 2003 film Rosenstrasse, and the 2004 TV movie, The Other Woman (also starring Sukowa). Sukowa had previously embodied German-Jewish revolutionary Rosa Luxemburg in Von Trotta’s acclaimed 1986 film of the same name. Katz also wrote the 2011 film Remembrance, about a couple who manage to escape Auschwitz during World War II, only to be separated, and then reunite 30 years later. Camera In The Sun sat down with Katz as she promoted Arendt‘s run of screenings at Manhattan’s Film Forum in June 2013, and discussed its subject’s complicated personality, and continued influence on the way people think about a variety of subjects — especially the Holocaust.

How familiar were you with Hannah Arendt’s work prior to writing the film?

I was not very familiar with Hannah Arendt‘s work. However, I grew up on the Upper West Side of New York. My father was a German-Jewish emigre, a philosopher and an academic — as were his brothers. And I was actually sitting on the 104 bus on Broadway with Margarethe, when she turned to me and said, “What about a film about Hannah Arendt?” And I said, “Fantastic. What a great idea.” I’m not really sure why I said that. I knew [Arendt] was a fascinating figure. I knew, as I put it in my next sentence, that she caused a lot of arguments, and had made a lot of people unhappy. And I knew she was incredibly important and had done something outrageous. And that was nearly the full extent of my knowledge of her. However, once you start to read about her, and realize who she was and what she’s done, you realize you’ve been hearing about her your whole life. Because for my generation especially, she completely redefined the discussion of the Holocaust. You cannot talk about National Socialism without reference to the idea of “the desk murderer,” of “just following orders,” or finally, her famous expression, “the banality of evil.” And so, you might not have known to whom you should attach those ideas, but they were all attached to her.

I was not very familiar with Hannah Arendt‘s work. However, I grew up on the Upper West Side of New York. My father was a German-Jewish emigre, a philosopher and an academic — as were his brothers. And I was actually sitting on the 104 bus on Broadway with Margarethe, when she turned to me and said, “What about a film about Hannah Arendt?” And I said, “Fantastic. What a great idea.” I’m not really sure why I said that. I knew [Arendt] was a fascinating figure. I knew, as I put it in my next sentence, that she caused a lot of arguments, and had made a lot of people unhappy. And I knew she was incredibly important and had done something outrageous. And that was nearly the full extent of my knowledge of her. However, once you start to read about her, and realize who she was and what she’s done, you realize you’ve been hearing about her your whole life. Because for my generation especially, she completely redefined the discussion of the Holocaust. You cannot talk about National Socialism without reference to the idea of “the desk murderer,” of “just following orders,” or finally, her famous expression, “the banality of evil.” And so, you might not have known to whom you should attach those ideas, but they were all attached to her.

How did you decide which part of her life to focus on?

When I said, “Fantastic,” Margarethe answered, “But she’s a thinker. What are we going to show?” And I should say that now that we’ve chosen these four years when she attended the trial and wrote about it and generated this enormous controversy, it seems obvious. But it was by no means obvious  when we started. We read for a minimum of a year before even putting pen to paper. We read biographies. There are about ten published volumes of correspondence. Nobody wrote more letters than Hannah Arendt. And we tried to do her whole life, because she had a fascinating life. She was thrown out of Germany as a Jew; imprisoned in France as a German; and made her way to America, where she really became a famous intellectual with her first book, The Origins of Totalitarianism. And it was all intriguing and important. And it all fueled her as a woman and a thinker. But you couldn’t do justice to it. And when we decided to look at her life through the lens of Eichmann, it immediately became the “Aha” moment. Well, of course. Because it offers you the possibility to engage in the activity of thinking. Because she was not only doing something, going to a trial, but she had a person to confront. And that was the person of Eichmann. And that’s why it had to be that we used the real man. Because we had to see what she was seeing. We had to be with her in that encounter. And that gave us the possibility to bring thinking alive. To show not just that she was writing, but what and who she was writing about. So the person she was writing about is a constant figure in the film, as are her friends and colleagues who are concerned with what she is seeing. And they’re telling her to see it in a different way. So it became very active.

when we started. We read for a minimum of a year before even putting pen to paper. We read biographies. There are about ten published volumes of correspondence. Nobody wrote more letters than Hannah Arendt. And we tried to do her whole life, because she had a fascinating life. She was thrown out of Germany as a Jew; imprisoned in France as a German; and made her way to America, where she really became a famous intellectual with her first book, The Origins of Totalitarianism. And it was all intriguing and important. And it all fueled her as a woman and a thinker. But you couldn’t do justice to it. And when we decided to look at her life through the lens of Eichmann, it immediately became the “Aha” moment. Well, of course. Because it offers you the possibility to engage in the activity of thinking. Because she was not only doing something, going to a trial, but she had a person to confront. And that was the person of Eichmann. And that’s why it had to be that we used the real man. Because we had to see what she was seeing. We had to be with her in that encounter. And that gave us the possibility to bring thinking alive. To show not just that she was writing, but what and who she was writing about. So the person she was writing about is a constant figure in the film, as are her friends and colleagues who are concerned with what she is seeing. And they’re telling her to see it in a different way. So it became very active.

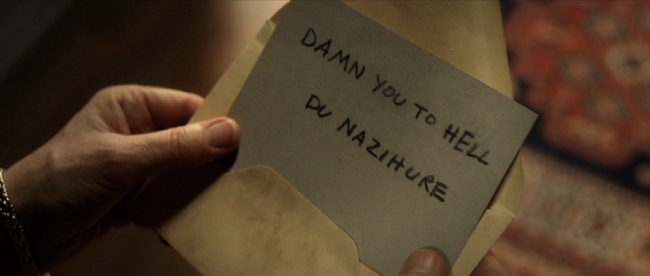

I also want to say it brought her thinking to life, but it also brings the woman to life. Because her life was very much defined by exile. And anybody who’s been exiled from their country, as my own father was from Germany, you never lose that fear. So the controversy that was generated in America was fearful to her, not just on an intellectual level. It was painful to her that she’d hurt so many people, but it allowed us to see the lonely side of her, the frightened side of her. And that was very important for such a publicly — sometimes people have called her “arrogant” — public thinker and speaker, who spoke her ideas so boldly. You could see the personal side. And that was deeply important to the film.

How did you approach the criticisms of Arendt for her take on Jewish complicity in the Holocaust?

The famous ten pages was ten pages of the 300-page book where she talks about the role of the Jewish leaders — we must be very careful in not saying “the Jewish people” — in Eichmann’s work. The first thing that I think is important to say is that Hannah Arendt wrote many letters about how painful it was for her to see these survivors being used, being made to relive their stories. It was very important to see this heartbreaking moment where one of the survivors who’s testifying can’t go on, and he actually faints. Because we really understand how, for her, many of these stories had nothing to do with the crimes of Eichmann. Because she’s very clear. On trial is a man. History is not on trial. No “ism” is on trial. Not even Antisemitism. And to make these people suffer, hurt her a great deal. And that was important for us to show as a framework for this larger discussion about the Jewish leaders. And I should say that we had an Israeli co-production on the film. We had a very intelligent Israeli co-producer. And when he read the script, he said, “You know, I’m missing a scene where we don’t just say, ‘OK, it was a show trial.’ I think it’s important for the larger audience to understand why that was important for Israel, why that was important for Ben-Gurion.” And so there’s the scene where she’s very upset, and she’s speaking to Kurt Blumenfeld, and he says, “Be a little patient with us. You have to understand that the young people today believe that the only ones who survived were the whores and the crooks. And they have to have to be made to understand what we suffered, and that there were some courageous people, and this trial is a chance to do that.” And it was was very much thanks to the Israeli producer that that scene is in. So it adds a greater context to the trial in Israel, and gives the two sides: The side that

The famous ten pages was ten pages of the 300-page book where she talks about the role of the Jewish leaders — we must be very careful in not saying “the Jewish people” — in Eichmann’s work. The first thing that I think is important to say is that Hannah Arendt wrote many letters about how painful it was for her to see these survivors being used, being made to relive their stories. It was very important to see this heartbreaking moment where one of the survivors who’s testifying can’t go on, and he actually faints. Because we really understand how, for her, many of these stories had nothing to do with the crimes of Eichmann. Because she’s very clear. On trial is a man. History is not on trial. No “ism” is on trial. Not even Antisemitism. And to make these people suffer, hurt her a great deal. And that was important for us to show as a framework for this larger discussion about the Jewish leaders. And I should say that we had an Israeli co-production on the film. We had a very intelligent Israeli co-producer. And when he read the script, he said, “You know, I’m missing a scene where we don’t just say, ‘OK, it was a show trial.’ I think it’s important for the larger audience to understand why that was important for Israel, why that was important for Ben-Gurion.” And so there’s the scene where she’s very upset, and she’s speaking to Kurt Blumenfeld, and he says, “Be a little patient with us. You have to understand that the young people today believe that the only ones who survived were the whores and the crooks. And they have to have to be made to understand what we suffered, and that there were some courageous people, and this trial is a chance to do that.” And it was was very much thanks to the Israeli producer that that scene is in. So it adds a greater context to the trial in Israel, and gives the two sides: The side that  Hannah Arendt was experiencing, and the side that many Israelis have about the trial. So that was very, very important. About the Jewish leaders, I’ll echo Hannah Arendt, who said, “I was just reporting.” And yet, I’ll deepen that. The Jewish leaders did testify at the trial. We have one of them in the film. But of course she has her famous interpretation, where she says, “This is the darkest chapter of the whole dark story.” By that she meant the complicity of some Jewish leaders with Eichmann in deporting the Jews. When she was attacked for that line, I read a really interesting correspondence in her book of Jewish writings. She said, “I didn’t say that. I said, ‘To a Jew, it’s the darkest chapter in the whole dark story.'” And for her, the fact that certain Jewish leaders were forced in a way to be complicit with National Socialism was heartbreaking for her, and for Jews. And I think it was a shock to her that that was taken as a criticism from the outside. It was very much a criticism from the inside. And the other piece of that puzzle, she wasn’t the first person to talk about it. Raul Hilberg had already written a whole book about the complicity of the Jewish leaders together with the Nazis, and she was actually quoting him. In fact, in the articles, at first she didn’t cite him. And when she wrote the book, she did cite his book. So I think that was the second shock. She didn’t bring this before the public for the first time. But she did bring it before the public with a certain tone that people objected to.

Hannah Arendt was experiencing, and the side that many Israelis have about the trial. So that was very, very important. About the Jewish leaders, I’ll echo Hannah Arendt, who said, “I was just reporting.” And yet, I’ll deepen that. The Jewish leaders did testify at the trial. We have one of them in the film. But of course she has her famous interpretation, where she says, “This is the darkest chapter of the whole dark story.” By that she meant the complicity of some Jewish leaders with Eichmann in deporting the Jews. When she was attacked for that line, I read a really interesting correspondence in her book of Jewish writings. She said, “I didn’t say that. I said, ‘To a Jew, it’s the darkest chapter in the whole dark story.'” And for her, the fact that certain Jewish leaders were forced in a way to be complicit with National Socialism was heartbreaking for her, and for Jews. And I think it was a shock to her that that was taken as a criticism from the outside. It was very much a criticism from the inside. And the other piece of that puzzle, she wasn’t the first person to talk about it. Raul Hilberg had already written a whole book about the complicity of the Jewish leaders together with the Nazis, and she was actually quoting him. In fact, in the articles, at first she didn’t cite him. And when she wrote the book, she did cite his book. So I think that was the second shock. She didn’t bring this before the public for the first time. But she did bring it before the public with a certain tone that people objected to.

Do you see any similarities in the characters of Rosa Luxemberg and Hannah Arendt?

First of all, I should say Hannah Arendt was an enormous fan of Rosa Luxemburg, and Hannah Arendt’s mother was an enormous fan of Rosa Luxemburg. And I think that that was a very important point for Margarethe Von Trotta and Barbara Sukowa naturally, who had worked with Rosa Luxemberg so deeply in their great film. Similarities? Both are intelligent Jewish women. That’s kind of a similarity. Though it could probably be said of many thousands of intelligent Jewish women. Margarethe makes a very interesting point. She said Rosa Luxemburg was looking forward to the century with hope. She thought that the 20th Century would be a kind of Utopian age where all her non-violent dreams would come to light. That the folly of World War I, that we would learn from that and go forward with great optimism. Of course, Rosa Luxemburg was in many ways, as Margarethe likes to say, “One of the first victims of the Nazis.” Because the Freikorps who murdered her for her beliefs went on to become Nazis some years later. Hannah Arendt is on the other end of the 20th Century tragedy. She’s looking back on what was anything but a century of hope, and trying to understand. So I wouldn’t necessarily call them similar. But they bookend, in a way, these tragic events of the 20th century in a very powerful and meaningful way.

First of all, I should say Hannah Arendt was an enormous fan of Rosa Luxemburg, and Hannah Arendt’s mother was an enormous fan of Rosa Luxemburg. And I think that that was a very important point for Margarethe Von Trotta and Barbara Sukowa naturally, who had worked with Rosa Luxemberg so deeply in their great film. Similarities? Both are intelligent Jewish women. That’s kind of a similarity. Though it could probably be said of many thousands of intelligent Jewish women. Margarethe makes a very interesting point. She said Rosa Luxemburg was looking forward to the century with hope. She thought that the 20th Century would be a kind of Utopian age where all her non-violent dreams would come to light. That the folly of World War I, that we would learn from that and go forward with great optimism. Of course, Rosa Luxemburg was in many ways, as Margarethe likes to say, “One of the first victims of the Nazis.” Because the Freikorps who murdered her for her beliefs went on to become Nazis some years later. Hannah Arendt is on the other end of the 20th Century tragedy. She’s looking back on what was anything but a century of hope, and trying to understand. So I wouldn’t necessarily call them similar. But they bookend, in a way, these tragic events of the 20th century in a very powerful and meaningful way.

Is it a challenge to bring something new to writing a film about the Holocaust?

I think that you can only write dramatically, in my opinion, about the Holocaust when there is something new. In the case of Remembrance, I remember getting the request from the producer. I saw the word “Auschwitz” and thought, “I could never really write about Auschwitz. I can’t do that. I don’t think I would know how.” And then I heard the story of these two people — that it was a love story; that it was an escape from Auschwitz; that it was a successful escape; that I learned there  were 600 escapes. That was all new to me. And the resistance within the camp was all new to me. And the idea that a non-Jewish Polish prisoner-of-war fell in love with a Jewish girl, dressed up as an SS officer, and succeeds in escaping the camp, only to find out he was the fourth person who did that — it was so amazing to me, that I thought, “This is not just ‘Can I realize the reality?’ I have my small corner of the camp experience that I’ve never heard of, that people I know don’t know about. And I can talk about that.” Hannah Arendt of course is much, much different. Because she not only experienced it, but she influenced the way we think about it. She is to me one of the greatest thinkers of the 20th Century. As I said earlier, she redefined the discussion of the Holocaust forever. And that’s not “What is it like to write about the Holocaust?” That’s “What is it like to write about a great thinker who had a profound influence on the way we judge these very important events of the past?”

were 600 escapes. That was all new to me. And the resistance within the camp was all new to me. And the idea that a non-Jewish Polish prisoner-of-war fell in love with a Jewish girl, dressed up as an SS officer, and succeeds in escaping the camp, only to find out he was the fourth person who did that — it was so amazing to me, that I thought, “This is not just ‘Can I realize the reality?’ I have my small corner of the camp experience that I’ve never heard of, that people I know don’t know about. And I can talk about that.” Hannah Arendt of course is much, much different. Because she not only experienced it, but she influenced the way we think about it. She is to me one of the greatest thinkers of the 20th Century. As I said earlier, she redefined the discussion of the Holocaust forever. And that’s not “What is it like to write about the Holocaust?” That’s “What is it like to write about a great thinker who had a profound influence on the way we judge these very important events of the past?”

What was your father’s experience as a German exile in the run-up to World War II?

He left in 1936. He left, as many Germans did, on a Czech passport. He went to Switzerland to school for two years. His brother went to Italy. He had a younger brother who left with his mother in a baggage car. They had the more dramatic escape. My grandfather was the last to leave, because he was actually very instrumental in helping a lot of people in his community leave. And my father didn’t see his family for two years, because basically at 17 you’re told, “You can get to Czechoslovakia. You have a place in a school in Switzerland. Come to America however you can.” And that’s what they did. And he arrived here in America in 1940 with his entire immediate family, quite fortunately.

I grew up in that generation where, as a child, none of this was talked about. I was the generation of children that were not to be raised with the victim mentality, who were not be told too much about the horrors of what went before. So he didn’t speak very much about that. He never spoke German to me. German was not spoken in our household. It was many, many years later, he actually received a Guggenheim fellowship — he was a philosophy professor — to do a study of German students and their reaction to authority. He went back to Germany for the first time in the ’70s, and he lived there for a year, and he made German friends, and he visited the town where he was from. And it was there that he began to be able to accept Germany and Germans again. Obviously as a philosopher, he was very steeped in German background and education. But it took a long time before he could go back, and have these kinds of open discussions. That was by no means true for everyone, but it was true for him.

Do you plan to return to the subject of the Holocaust in your future screenwriting?

Let’s say in the context of Rosenstrasse, Remembrance and Hannah Arendt — every time you go through this, and you have to go through such an enormous amount of research. So much of which is so tragic, and so difficult to be articulate about and intelligent about. I mean, David Grossman has a great expression. He says, “I can’t touch the wound, unless I’m prepared to be intelligent about it.” And every time, you say, “OK, I think I’ve said my piece.” But you don’t think like that. You don’t think, “I’ll do this period of history” or “I’ll do that period of history.” You see what comes to you, and how the story speaks to you, and how the characters speak to you. And I can’t say that I will never encounter another character from wartime Germany that I won’t find fascinating. I should say at the moment I’m actually writing a book about the partnership of Bertolt Brecht and Kurt Weill. So I have been living in the Weimar Republic for last two years. So on that level, I’m not yet done by any means. But after that? One never knows.

Let’s say in the context of Rosenstrasse, Remembrance and Hannah Arendt — every time you go through this, and you have to go through such an enormous amount of research. So much of which is so tragic, and so difficult to be articulate about and intelligent about. I mean, David Grossman has a great expression. He says, “I can’t touch the wound, unless I’m prepared to be intelligent about it.” And every time, you say, “OK, I think I’ve said my piece.” But you don’t think like that. You don’t think, “I’ll do this period of history” or “I’ll do that period of history.” You see what comes to you, and how the story speaks to you, and how the characters speak to you. And I can’t say that I will never encounter another character from wartime Germany that I won’t find fascinating. I should say at the moment I’m actually writing a book about the partnership of Bertolt Brecht and Kurt Weill. So I have been living in the Weimar Republic for last two years. So on that level, I’m not yet done by any means. But after that? One never knows.