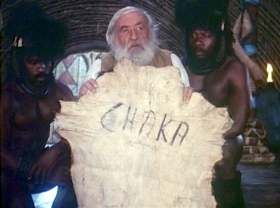

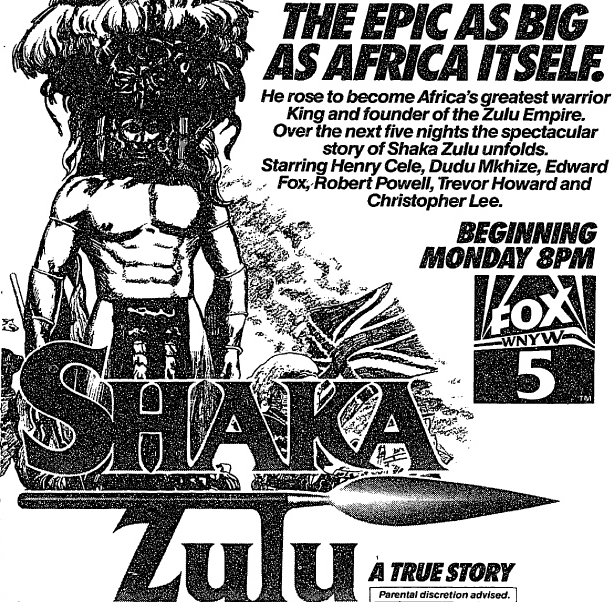

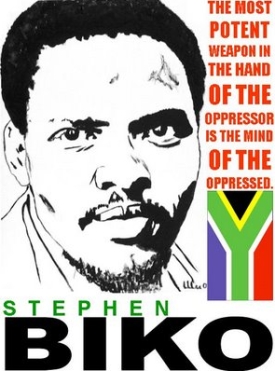

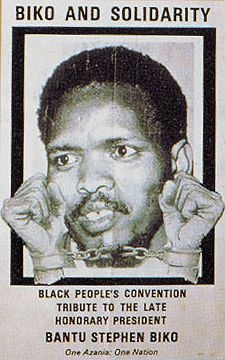

Who: Joshua Sinclair is an Austria-based, American screenwriter and medical doctor. From a young age, Sinclair had an interest in film and medicine — the latter bringing him to South Africa, where he was inspired to write a historical novelization of the reign of 19th-Century Zulu king Shaka. Sinclair’s book was later adapted into the 1986 miniseries Shaka Zulu, which he also wrote. Commissioned by the South African Broadcasting Corporation in the midst of an international cultural boycott, the series was a massive hit, and its syndication proved highly profitable for its distributor — but not its writer. With a long cut of over 8 hours, the $12 million production was shot on location in South Africa with director William C. Faure and cinematographer Alec Mills. Sinclair remained in Europe, collaborating from afar, having signed an agreement with the United Nations to not return to South Africa until apartheid was abolished. While this move cost him 8% of Shaka‘s profits, Sinclair sued South Africa through the International Court to ensure that the shooting script would meet his approval, and not be altered for use as propaganda. In 2002, for his work on Shaka Zulu and against apartheid, Sinclair received a commendation from the U.S. Senate and House of Representatives. This, after receiving commendations in 2000 from the NAACP and the Zulu Nation. Prior to Shaka, Sinclair had addressed apartheid as co-writer of The Biko Inquest. An adaptation of a stage play directed by and costarring Albert Finney, the film looks at the investigation into the violent death of anti-apartheid activist Stephen Biko while in police custody in 1977. Camera In The Sun spoke with Sinclair about the making and legacy of Shaka Zulu, his opinion of the semi-sequel to it that he wrote and directed 15 years later, and his take on South Africa’s anti-apartheid movement.

Who: Joshua Sinclair is an Austria-based, American screenwriter and medical doctor. From a young age, Sinclair had an interest in film and medicine — the latter bringing him to South Africa, where he was inspired to write a historical novelization of the reign of 19th-Century Zulu king Shaka. Sinclair’s book was later adapted into the 1986 miniseries Shaka Zulu, which he also wrote. Commissioned by the South African Broadcasting Corporation in the midst of an international cultural boycott, the series was a massive hit, and its syndication proved highly profitable for its distributor — but not its writer. With a long cut of over 8 hours, the $12 million production was shot on location in South Africa with director William C. Faure and cinematographer Alec Mills. Sinclair remained in Europe, collaborating from afar, having signed an agreement with the United Nations to not return to South Africa until apartheid was abolished. While this move cost him 8% of Shaka‘s profits, Sinclair sued South Africa through the International Court to ensure that the shooting script would meet his approval, and not be altered for use as propaganda. In 2002, for his work on Shaka Zulu and against apartheid, Sinclair received a commendation from the U.S. Senate and House of Representatives. This, after receiving commendations in 2000 from the NAACP and the Zulu Nation. Prior to Shaka, Sinclair had addressed apartheid as co-writer of The Biko Inquest. An adaptation of a stage play directed by and costarring Albert Finney, the film looks at the investigation into the violent death of anti-apartheid activist Stephen Biko while in police custody in 1977. Camera In The Sun spoke with Sinclair about the making and legacy of Shaka Zulu, his opinion of the semi-sequel to it that he wrote and directed 15 years later, and his take on South Africa’s anti-apartheid movement.

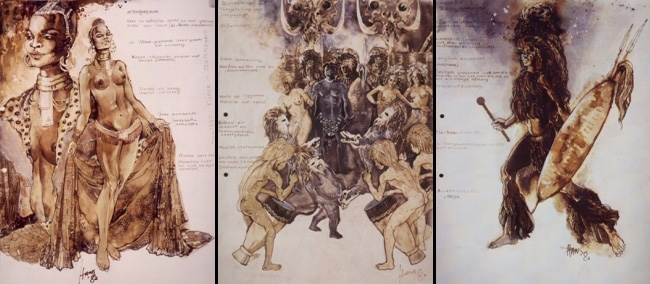

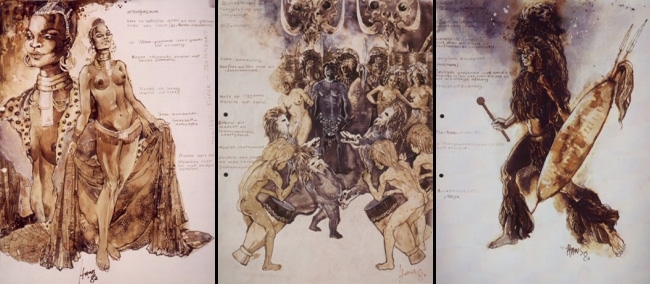

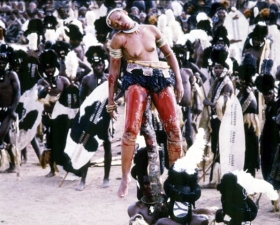

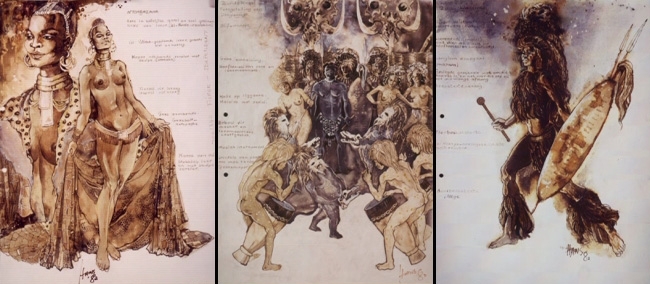

Shaka watches his people celebrate, after killing his half-brother and seizing the Zulu throne — from Episode 6 of Shaka Zulu:

Shaka: “Look at them, Ngomane. They must be asking themselves, ‘What is Shaka? Where is he going? What does he want?'”

Ngomane: “And what does he want?”

Shaka: “Oh, they’ll soon learn, Ngomane. There will be but one reality — War.”

Ngomane: “And when there are no wars?”

Shaka: “I’ll create them, Ngomane.”

How did your interest in Shaka come about?

I was studying medicine, and on my way over South Africa to India, where I was going to Grant University for a while to specialize in tropical diseases. I was at Baragwanath Hospital in Soweto, and it was my first impact really with Africa. I had already written two other films. Because I started writing films when I was 14. I didn’t want to do it for a living. I wanted to be a missionary. That’s why I studied medicine and theology. But I wrote Lili Marleen with [Rainer Werner] Fassbinder, and Just a Gigolo I wrote when I was 18. Then I went to Johns Hopkins, specializing in tropical diseases, and I was going to go back. Some people heard that I was in the film business. I was sitting there in [Baragwanath] hospital, minding my own business, and they said, “Would you be interested in doing Shaka Zulu?” I said, “Yes.” But I didn’t know anything about it. So they gave me a couple of books, and I read them. For me, [Shaka’s story] was very Shakespearean. But I didn’t understand completely why I was doing this. Then, working in Soweto and seeing the situation with apartheid, I became sort of a crusader. So I said, “I want Shaka Zulu to be a way for South Africa to liberate itself from apartheid.” That is, I wanted South Africans themselves and the whole world to know that the people who have no rights here have a prouder background and culture than the people who deny them those rights. Because the people who deny them those rights just landed here, because they were outcasts from their own place. The people they found there, they didn’t know what was — as the Victorians said in their terms — “Negro”, and what was “Bantu.” They had all these weird terms for them.

I was studying medicine, and on my way over South Africa to India, where I was going to Grant University for a while to specialize in tropical diseases. I was at Baragwanath Hospital in Soweto, and it was my first impact really with Africa. I had already written two other films. Because I started writing films when I was 14. I didn’t want to do it for a living. I wanted to be a missionary. That’s why I studied medicine and theology. But I wrote Lili Marleen with [Rainer Werner] Fassbinder, and Just a Gigolo I wrote when I was 18. Then I went to Johns Hopkins, specializing in tropical diseases, and I was going to go back. Some people heard that I was in the film business. I was sitting there in [Baragwanath] hospital, minding my own business, and they said, “Would you be interested in doing Shaka Zulu?” I said, “Yes.” But I didn’t know anything about it. So they gave me a couple of books, and I read them. For me, [Shaka’s story] was very Shakespearean. But I didn’t understand completely why I was doing this. Then, working in Soweto and seeing the situation with apartheid, I became sort of a crusader. So I said, “I want Shaka Zulu to be a way for South Africa to liberate itself from apartheid.” That is, I wanted South Africans themselves and the whole world to know that the people who have no rights here have a prouder background and culture than the people who deny them those rights. Because the people who deny them those rights just landed here, because they were outcasts from their own place. The people they found there, they didn’t know what was — as the Victorians said in their terms — “Negro”, and what was “Bantu.” They had all these weird terms for them.  But they didn’t know what they were. If you go back to the 1600s, they didn’t know if they were human, or if they weren’t human. So I said, “It’s time, because of apartheid, to show that Shaka and the Zulu Empire was gigantic.” It was an army of a million-strong. It is the mythological movie of all time, and it comes out of Africa, not out of Europe. Shaka made Alexander the Great look like a wuss. He literally went from 2,000 to 1 million standing. These guys jogged 50 miles every day without shoes on. It was just incredible. But above all, I wanted to show “This is an Africa that nobody ever stopped to look at, and nobody ever stopped to think about.”

But they didn’t know what they were. If you go back to the 1600s, they didn’t know if they were human, or if they weren’t human. So I said, “It’s time, because of apartheid, to show that Shaka and the Zulu Empire was gigantic.” It was an army of a million-strong. It is the mythological movie of all time, and it comes out of Africa, not out of Europe. Shaka made Alexander the Great look like a wuss. He literally went from 2,000 to 1 million standing. These guys jogged 50 miles every day without shoes on. It was just incredible. But above all, I wanted to show “This is an Africa that nobody ever stopped to look at, and nobody ever stopped to think about.”

What I wanted to show from a medical point of view, and also because I love mythology, is that this great empire was intelligent enough to call the bluff of our culture. And that’s what Shaka did. That’s why I have at the beginning, he kills the girl and says, “Resurrect her. Didn’t you say you can resurrect?”  That is a real story that happened to me in India when I was a doctor there. Somebody called me and said, “I hear from the sisters that you know how to resurrect.” And I couldn’t suddenly go into a whole lesson of theology and doxology there. So I had to say, “Whoa, wait a minute. What are we talking about?” And they said, “I want you to bring her back to life.” Then I went through a whole other [approach] of, “Do you see where she is? Do you really want her to come back from there?” And so, I got out of that.

That is a real story that happened to me in India when I was a doctor there. Somebody called me and said, “I hear from the sisters that you know how to resurrect.” And I couldn’t suddenly go into a whole lesson of theology and doxology there. So I had to say, “Whoa, wait a minute. What are we talking about?” And they said, “I want you to bring her back to life.” Then I went through a whole other [approach] of, “Do you see where she is? Do you really want her to come back from there?” And so, I got out of that.

Who commissioned Shaka Zulu, and who profited from it?

It was being commissioned by South African Broadcasting. Because of the cultural boycott, they didn’t want to appear as the ones who were commissioning it. They wanted to do it for TV3 — and TV3 is in Zulu. I said to my friends back home, “I’m writing a movie in Zulu.” And they were laughing, “You’re out of your mind. It’s not gonna go anywhere.” It ended up being the #1 syndicated series of all time. But I wrote it in such a way that SABC could not possibly have it on TV3. It had to be TV1. I mean, it’s been seen by 3 billion people, maybe. We don’t know, because Harmony Gold [USA] has never told anybody how much Shaka Zulu made. Because they made a fortune.

Because of the cultural boycott, they didn’t want to appear as the ones who were commissioning it. They wanted to do it for TV3 — and TV3 is in Zulu. I said to my friends back home, “I’m writing a movie in Zulu.” And they were laughing, “You’re out of your mind. It’s not gonna go anywhere.” It ended up being the #1 syndicated series of all time. But I wrote it in such a way that SABC could not possibly have it on TV3. It had to be TV1. I mean, it’s been seen by 3 billion people, maybe. We don’t know, because Harmony Gold [USA] has never told anybody how much Shaka Zulu made. Because they made a fortune.

Harmony Gold was given Shaka as a gift. It was used to bypass the cultural boycott. The head of Harmony Gold, Frank Agrama has recently been convicted of tax fraud for his work with Silvio Berlusconi, and got three years in jail — which he won’t serve. But Harmony Gold is the name of a mine is South Africa. They needed to bypass the cultural boycott. I didn’t even realize this was happening, until years later. Because I had 8% of the income, and I never got that. I was just given a check once by Harmony Gold for $75,000. They have made $500 million, that we know of, from Shaka. For a TV series, that’s a lot. Harmony Gold, before Shaka Zulu, was a suite of 5 rooms above the Whisky a Go Go. It wasn’t called Harmony Gold. It was called “FAR International” — for Farouk Agrama International. After Shaka Zulu, they suddenly had their own building on Sunset Boulevard, and downstairs was this gigantic cut-out of Shaka. So that  sort of tells you what the deal was. South African Broadcasting did something very strange for a production company. SABC put up the entire amount of the film, which cost 10 million rand — or about $12 million. The rand was stronger than the dollar in those days. SABC put up all the money, but they gave 60% of the income to Harmony Gold, plus expenses. That’s unheard of. All Harmony Gold had to do was sell the movie, which was pretty easy. Literally, Harmony Gold could have, and did, rake in 80% of the income of the film gross. South African Broadcasting didn’t even recoup, according to them, the 10 million rand that they had put up in the first place. So then there were monies being funneled into a bank in Switzerland, which I think Agrama had together with Berlusconi. Berlusconi was using Agrama as a fence, and South African Broadcasting was using Agrama as a fence. According to the cultural boycott, countries could not sell to SABC. So SABC didn’t appear as the producers. Harmony Gold appeared as the producers. Harmony Gold would get the money and, through a Swiss bank, give SABC back that money.

sort of tells you what the deal was. South African Broadcasting did something very strange for a production company. SABC put up the entire amount of the film, which cost 10 million rand — or about $12 million. The rand was stronger than the dollar in those days. SABC put up all the money, but they gave 60% of the income to Harmony Gold, plus expenses. That’s unheard of. All Harmony Gold had to do was sell the movie, which was pretty easy. Literally, Harmony Gold could have, and did, rake in 80% of the income of the film gross. South African Broadcasting didn’t even recoup, according to them, the 10 million rand that they had put up in the first place. So then there were monies being funneled into a bank in Switzerland, which I think Agrama had together with Berlusconi. Berlusconi was using Agrama as a fence, and South African Broadcasting was using Agrama as a fence. According to the cultural boycott, countries could not sell to SABC. So SABC didn’t appear as the producers. Harmony Gold appeared as the producers. Harmony Gold would get the money and, through a Swiss bank, give SABC back that money.  Now, you don’t set something like that up with a guy like Frank Agrama or Berlusconi. Because you probably are setting yourself up to not see anything. So [Agrama] came in, he kept the 60%. And then he started to pay through the Swiss bank, through a fence company. They then were paying SABC part of the money. A lot of it stayed in the Swiss bank, and never hit South Africa. The South Africans themselves didn’t want it to hit South Africa. So the involvement was, [Agrama] did some sales that put Harmony Gold on the map. They gave Harmony Gold a name, which is a gold mine in South Africa. It made [Agrama] rich overnight. And in a way it helped Shaka, because they sold it everywhere. But many people thought that Harmony Gold had produced it, and had paid for it — when in fact, that’s not what happened at all. I told the head of the legal department at SABC, “You guys are nuts.” He came to see me in London, because he was the one who negotiated the deal where everything had to be signed, after I sued them. We became friends, actually. He understood my point of view, and he actually honored it. I said, “You guys are nuts. This is a chance

Now, you don’t set something like that up with a guy like Frank Agrama or Berlusconi. Because you probably are setting yourself up to not see anything. So [Agrama] came in, he kept the 60%. And then he started to pay through the Swiss bank, through a fence company. They then were paying SABC part of the money. A lot of it stayed in the Swiss bank, and never hit South Africa. The South Africans themselves didn’t want it to hit South Africa. So the involvement was, [Agrama] did some sales that put Harmony Gold on the map. They gave Harmony Gold a name, which is a gold mine in South Africa. It made [Agrama] rich overnight. And in a way it helped Shaka, because they sold it everywhere. But many people thought that Harmony Gold had produced it, and had paid for it — when in fact, that’s not what happened at all. I told the head of the legal department at SABC, “You guys are nuts.” He came to see me in London, because he was the one who negotiated the deal where everything had to be signed, after I sued them. We became friends, actually. He understood my point of view, and he actually honored it. I said, “You guys are nuts. This is a chance  for you to show the world that you’re doing something good for the Black people. You’re showing their heritage. You’re showing how important they were to the history of South Africa. You’re doing something good. In a way, it makes up for many of the mistakes of apartheid. Why wouldn’t you want people to know you are doing it? Why wouldn’t you want people to know that you’re spending 10 million rand on the Zulus history? That’s a great plus for you.” They didn’t get it. They said, “Oh, but people won’t buy it from us, because of the cultural boycott.” I said, “You can burst the cultural boycott by just making a case for what you’re doing. I think people will understand. Just go out there and tell the truth. ‘We’re making this, because we believe that the heritage of the Black people and the Zulus is as important as that of the Afrikaners and the Brits in South Africa. We’re spending government money to make this, which is going to be one of the biggest epic series ever made. And we’re doing it for the Zulus. Not for the Afrikaners. Not for the Brits. For the Zulus.’ They’ll like that. They’ll buy it from you.” But they didn’t get that. They were afraid.

for you to show the world that you’re doing something good for the Black people. You’re showing their heritage. You’re showing how important they were to the history of South Africa. You’re doing something good. In a way, it makes up for many of the mistakes of apartheid. Why wouldn’t you want people to know you are doing it? Why wouldn’t you want people to know that you’re spending 10 million rand on the Zulus history? That’s a great plus for you.” They didn’t get it. They said, “Oh, but people won’t buy it from us, because of the cultural boycott.” I said, “You can burst the cultural boycott by just making a case for what you’re doing. I think people will understand. Just go out there and tell the truth. ‘We’re making this, because we believe that the heritage of the Black people and the Zulus is as important as that of the Afrikaners and the Brits in South Africa. We’re spending government money to make this, which is going to be one of the biggest epic series ever made. And we’re doing it for the Zulus. Not for the Afrikaners. Not for the Brits. For the Zulus.’ They’ll like that. They’ll buy it from you.” But they didn’t get that. They were afraid.

How much money did you make from Shaka Zulu?

I was writer, and I co-directed Shaka. I personally made $150,000 out of it, but I had 8% of the movie. Now, legally I can’t even sue. Why? The United Nations called me when I was working in India with Mother Teresa. So I had to have  pretty clean politics. They were saying, “OK, you’re writing Shaka Zulu. Where are you in this? You’re directing part of it, so where is the cultural boycott in all of this?” I said, “What do you mean?” They said, “We want you to sign that you will not return to South Africa until apartheid is abolished.” So I did. And because of that, [SABC] said, “Well, if you can’t come back, if you can’t be in South Africa, then we can’t give you the 8% of the movie.” So by signing that piece of paper, I gave up almost $20 million. At the age of 19-20, it would really have made a difference. But I would do it again, because you make it up anyway. The point is, you had to do it. The things I saw as a doctor, you had to do it. You couldn’t possibly not be on the side of these people. So I said, “OK.” But then I went to the International Court in the Hague, and I sued South Africa on the grounds that apartheid is against the Geneva Copyright Convention. I won. And I wanted each and every page in the script to be signed by myself and everybody else. It had to be shot the way it was written, so that it would not end up being propaganda for South Africa. It was a big fight, and I was fighting the government. But I won.

pretty clean politics. They were saying, “OK, you’re writing Shaka Zulu. Where are you in this? You’re directing part of it, so where is the cultural boycott in all of this?” I said, “What do you mean?” They said, “We want you to sign that you will not return to South Africa until apartheid is abolished.” So I did. And because of that, [SABC] said, “Well, if you can’t come back, if you can’t be in South Africa, then we can’t give you the 8% of the movie.” So by signing that piece of paper, I gave up almost $20 million. At the age of 19-20, it would really have made a difference. But I would do it again, because you make it up anyway. The point is, you had to do it. The things I saw as a doctor, you had to do it. You couldn’t possibly not be on the side of these people. So I said, “OK.” But then I went to the International Court in the Hague, and I sued South Africa on the grounds that apartheid is against the Geneva Copyright Convention. I won. And I wanted each and every page in the script to be signed by myself and everybody else. It had to be shot the way it was written, so that it would not end up being propaganda for South Africa. It was a big fight, and I was fighting the government. But I won.

What was your relationship like with Shaka Zulu director William C. Faure?

Bill Faure was a technician. I had the idea of doing Shaka, originally. He wanted to do Shaka because of the mythological point of view of it. We got together, and met in Europe, and worked on it. I wrote the script — basically, all of it alone. I can’t really write with others that well. Then I gave it to Bill,  who didn’t do much with the script. But he had a vision of what it could be for the South African people. But I never understood the politics of Bill. He was an Afrikaner, and he was Huguenot. So I never really understood whether he wanted it to be something that was propaganda for the Zulu people, or South Africa, or whether he was above it. I wanted to do something a-racial. The Prime Minister of the Zulu people, Gatsha Buthelezi and I met often. Because my scripts were translated into Zulu, and shown to the King. So he said, “It’s great that the guy who writes Shaka is not South African, not Black, and doesn’t really know the culture.” Why? Because I’m fresh. I can listen to what people are telling me, and it’s clean. I lived with the Zulus for 6 months. He said, “You can say things that we can’t say. We as Africans cannot say it, because of apartheid.” The White South African could not say it, or would not say it, because of apartheid. They were afraid, even Bill, to say something which would go counter-apartheid. Remember, when I wrote Shaka, apartheid was here to stay. Nobody thought it would disappear in the ’90s. It was here to stay, and I was

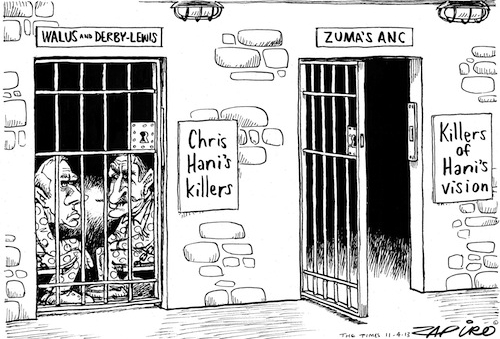

who didn’t do much with the script. But he had a vision of what it could be for the South African people. But I never understood the politics of Bill. He was an Afrikaner, and he was Huguenot. So I never really understood whether he wanted it to be something that was propaganda for the Zulu people, or South Africa, or whether he was above it. I wanted to do something a-racial. The Prime Minister of the Zulu people, Gatsha Buthelezi and I met often. Because my scripts were translated into Zulu, and shown to the King. So he said, “It’s great that the guy who writes Shaka is not South African, not Black, and doesn’t really know the culture.” Why? Because I’m fresh. I can listen to what people are telling me, and it’s clean. I lived with the Zulus for 6 months. He said, “You can say things that we can’t say. We as Africans cannot say it, because of apartheid.” The White South African could not say it, or would not say it, because of apartheid. They were afraid, even Bill, to say something which would go counter-apartheid. Remember, when I wrote Shaka, apartheid was here to stay. Nobody thought it would disappear in the ’90s. It was here to stay, and I was  against the current. But when Louis Nel, who was Minister of the Interior, became the head of SABC, they realized that Shaka was big enough to use as propaganda. That’s when I went to the International Court and said, “No, I didn’t write this for Goebbels. If I do a movie for the Nazis, I don’t want anything. Because I can’t do it.” I had 8%. That’s millions and millions of dollars. But if I had just not signed with the United Nations, [those against apartheid] would have said, “OK, you’re one of them.” Looking back on those days, do I wonder whether I did the right thing? No. It was then, and a piece of paper. You either signed it or you didn’t. People asked me, “Whose side are you on? Because there are people who are dying.” And I understood this more, maybe because I was a doctor. You actually see blood. So you’re saying, “They’re killing people.” After that, I did The Biko Inquest. Stephen Biko was killed. And I’m going to write about [the murdered] Chris Hani of the ANC. Anyway, Bill was on sort of both sides of the fence. Rightfully so, probably, because he lived there. I mean, imagine the late-’50s or ’60s in the [American] South, directing a movie about segregation and living in Lincoln, Alabama.

against the current. But when Louis Nel, who was Minister of the Interior, became the head of SABC, they realized that Shaka was big enough to use as propaganda. That’s when I went to the International Court and said, “No, I didn’t write this for Goebbels. If I do a movie for the Nazis, I don’t want anything. Because I can’t do it.” I had 8%. That’s millions and millions of dollars. But if I had just not signed with the United Nations, [those against apartheid] would have said, “OK, you’re one of them.” Looking back on those days, do I wonder whether I did the right thing? No. It was then, and a piece of paper. You either signed it or you didn’t. People asked me, “Whose side are you on? Because there are people who are dying.” And I understood this more, maybe because I was a doctor. You actually see blood. So you’re saying, “They’re killing people.” After that, I did The Biko Inquest. Stephen Biko was killed. And I’m going to write about [the murdered] Chris Hani of the ANC. Anyway, Bill was on sort of both sides of the fence. Rightfully so, probably, because he lived there. I mean, imagine the late-’50s or ’60s in the [American] South, directing a movie about segregation and living in Lincoln, Alabama.  You have to be careful, because [local racists] know where your family lives. Bill was very much in the To Kill a Mockingbird situation. In To Kill a Mockingbird, Atticus risked everything — including the welfare of his kids — by taking that stance. You can’t ask people to be heroes like that, unless they come from outside. You can import a hero. For locals, it’s difficult, because they’ve got too much at stake. They’ve got their house, their family, their everything. Bill was asked to be an Atticus, and he couldn’t do it. So that’s why I had to be the one who was the outsider who could take the blame. “Look, it’s Sinclair. He’s the idiot. He’s the one who doesn’t understand that apartheid is here to stay.” I said, “Apartheid is gonna be gone in five years.” And it was. I was arrested in South Africa, because of my work with the [African National Congress]. I even joined the ANC, to make matters worse. It was illegal, but I said, “In five years, it’s gonna be the ruling party.” Nobody believed that, because it’s just too absurd. It’s like saying, “America is going to be Communist the day after tomorrow.” Nobody would have believed it.

You have to be careful, because [local racists] know where your family lives. Bill was very much in the To Kill a Mockingbird situation. In To Kill a Mockingbird, Atticus risked everything — including the welfare of his kids — by taking that stance. You can’t ask people to be heroes like that, unless they come from outside. You can import a hero. For locals, it’s difficult, because they’ve got too much at stake. They’ve got their house, their family, their everything. Bill was asked to be an Atticus, and he couldn’t do it. So that’s why I had to be the one who was the outsider who could take the blame. “Look, it’s Sinclair. He’s the idiot. He’s the one who doesn’t understand that apartheid is here to stay.” I said, “Apartheid is gonna be gone in five years.” And it was. I was arrested in South Africa, because of my work with the [African National Congress]. I even joined the ANC, to make matters worse. It was illegal, but I said, “In five years, it’s gonna be the ruling party.” Nobody believed that, because it’s just too absurd. It’s like saying, “America is going to be Communist the day after tomorrow.” Nobody would have believed it.

As you couldn’t go to South Africa, what was your non-writing involvement in making Shaka?

My involvement was casting Henry Cele as Shaka Zulu, and Dudu Mkhize as Nandi. And there were just some strange stories. Some people wanted Dudu to go to Cannes with them. Because in Cannes, one of the heads of SABC thought it was OK for him to sleep with her, because she’s Black. But he couldn’t sleep with her in South Africa, because of apartheid. Really. This is the truth. They were taking a lot of the cast members to Cannes, so that they could sleep with them. And I was thinking, “You don’t have to go all the way to Cannes. You can go to Sun City and sleep with them, if you want to.” But isn’t that a little bit strange? Isn’t this about making a movie, more than casting people you can sleep with? Isn’t that a little grotesque? But this is a country where SABC had this gigantic building with wonderful carpets and everything else. It had more money than Paramount. But no software. No scripts. No nothing. Shaka blew them away, because they didn’t expect to do something that big. I also worked on the edit in Munich. Every single daily was sent to me. Because I had forced [SABC] to do that, to make sure that Shaka would never become propaganda. They had to send me all the dailies to make sure that it was being done properly. I was in contact constantly with Alec Mills. At the end of the day, Alec was the one who was responsible for the look of Shaka. Bill worked with the actors, and he did a good job. Alec didn’t just do camera. He did set-ups. He did everything. He storyboarded it, then sent me the storyboard. I had storyboarded it first, sent it to Alec, and met with him in London before he went to South Africa. And at the same time, I worked with the publicity of Shaka, together with the Artists Against Apartheid.

My involvement was casting Henry Cele as Shaka Zulu, and Dudu Mkhize as Nandi. And there were just some strange stories. Some people wanted Dudu to go to Cannes with them. Because in Cannes, one of the heads of SABC thought it was OK for him to sleep with her, because she’s Black. But he couldn’t sleep with her in South Africa, because of apartheid. Really. This is the truth. They were taking a lot of the cast members to Cannes, so that they could sleep with them. And I was thinking, “You don’t have to go all the way to Cannes. You can go to Sun City and sleep with them, if you want to.” But isn’t that a little bit strange? Isn’t this about making a movie, more than casting people you can sleep with? Isn’t that a little grotesque? But this is a country where SABC had this gigantic building with wonderful carpets and everything else. It had more money than Paramount. But no software. No scripts. No nothing. Shaka blew them away, because they didn’t expect to do something that big. I also worked on the edit in Munich. Every single daily was sent to me. Because I had forced [SABC] to do that, to make sure that Shaka would never become propaganda. They had to send me all the dailies to make sure that it was being done properly. I was in contact constantly with Alec Mills. At the end of the day, Alec was the one who was responsible for the look of Shaka. Bill worked with the actors, and he did a good job. Alec didn’t just do camera. He did set-ups. He did everything. He storyboarded it, then sent me the storyboard. I had storyboarded it first, sent it to Alec, and met with him in London before he went to South Africa. And at the same time, I worked with the publicity of Shaka, together with the Artists Against Apartheid.

What was your relationship like with Shaka Zulu star Henry Cele?

Henry became my brother. I love Henry. He came to visit me in jail. He said, “What are you doing in our jail?” Because I was up in Lesotho, and I had a really deep suntan. When they arrested me, on the form it said “Race of Mother” and “Race of Father”. Without thinking, I wrote, “Caucasian.” And then I looked again at “Race of Mother”, and I said, “Whoa, wait a minute. This is racist.” So I wrote, “African.” Because we’re all African. So they put me in the so-called “colored” jail, which is the mixed jail, and Henry came to see me.

Henry became my brother. I love Henry. He came to visit me in jail. He said, “What are you doing in our jail?” Because I was up in Lesotho, and I had a really deep suntan. When they arrested me, on the form it said “Race of Mother” and “Race of Father”. Without thinking, I wrote, “Caucasian.” And then I looked again at “Race of Mother”, and I said, “Whoa, wait a minute. This is racist.” So I wrote, “African.” Because we’re all African. So they put me in the so-called “colored” jail, which is the mixed jail, and Henry came to see me.

Henry was a magnificent character. He talked like [Shaka] all the time. Not just when he played Shaka. He was very generous. He gave 110%, always. After the passing of Henry, I became a close friend of his wife in South Africa, Jenny Hollander, and we talk regularly. Henry was Shaka. When I did Shaka 2, [the producers] wanted other people to play Shaka. They were pushing, pushing, pushing in America for an American to do it. And I said, “No, it’s gotta be Henry. Henry is Shaka.” And he remained Shaka. But nobody would cast him for anything else. In South Africa, it became impossible for him to be anything but Shaka. Because people, especially the Zulus, would say, “Well, how can you take Shaka and make him any other role?” Internationally, Shaka was so successful that people saw Henry, and they thought of Shaka. So it took somebody like Michael Douglas to see him as something different for The Ghost and the Darkness. But nobody else really saw him as anything different. So what Henry did was go on his own junket. He took his Shaka Zulu [outfit], and he went to Brazil and other places where they paid him to appear as Shaka. And he did this for most of his life, until I called him back for Shaka 2. He looks exactly the same as in the first Shaka, and he’s almost 50.

How did you originally go about casting Henry Cele as Shaka?

There was a lot of pressure from America, and also from South Africa to get an American to play Shaka. I said, “A Zulu has to play Shaka, or else you’re selling out your own people.” I mean, come on, you start out with the idea that it’s gonna be in Zulu. Now suddenly it’s not in Zulu. It’s in English.  Suddenly it’s a big production, and you’re putting a lot of money into it. Big American distribution is involved. And you want an American? Now you’re really selling out the whole thing. I said, “No, Shaka has to be Zulu. I promised that to the King.” Bill would rather have had Denzel Washington, or somebody else. But there was this guy who was a chauffeur for Siemens, which is a big company in Germany. It was Henry.

Suddenly it’s a big production, and you’re putting a lot of money into it. Big American distribution is involved. And you want an American? Now you’re really selling out the whole thing. I said, “No, Shaka has to be Zulu. I promised that to the King.” Bill would rather have had Denzel Washington, or somebody else. But there was this guy who was a chauffeur for Siemens, which is a big company in Germany. It was Henry.

I was in South Africa, and was interested in seeing what the difference was between buying a BMW in South Africa, and buying one in Europe. I was told the best place to check on that would be in Durban. So I went to a BMW dealer in Durban, and he said, “Let’s meet in a restaurant nearby.” So we met there, and we’re eating and speaking about it. He was German, so we were speaking German. And Henry, who understood German, was nearby. So Henry came over and talked to us in German, which is the last thing you would expect from a Zulu. So I turned, and looked at this gigantic guy, and I said, “My god, he’s wonderful.” Not only because he  was ripped, but because of the fact that he was stately. I thought, “This is the guy who has to play Shaka.” So I said, “We’re having casting for Shaka. Do you want to come?” And he said, “Sure.” We had the casting, and I said to Bill, “This is the perfect guy for Shaka.” And Bill didn’t want that, because he wanted an Englishman or an American to play Shaka. He said, “No,” because he saw that as a way of making himself more famous — by having a big name to play Shaka. And I said, “No, Shaka has to be Zulu. I promised that to the king. It has to be a Zulu. You can’t take anybody else but a Zulu. It would be an outrage for the Zulus to have Shaka played by an American or an Englishman.” Bill didn’t believe in that at all. He had done some documentaries for BOSS, which is the Bureau of State Security. So, that’s why I didn’t understand what his politics were. But he grabbed Shaka, because it was a good idea for him to do that. Then he started saying to people that he had had the idea of Shaka, which wasn’t true. My book came out long before Bill was even considered for that. In fact, originally, I was supposed to direct it. But I couldn’t, because of the cultural boycott.

was ripped, but because of the fact that he was stately. I thought, “This is the guy who has to play Shaka.” So I said, “We’re having casting for Shaka. Do you want to come?” And he said, “Sure.” We had the casting, and I said to Bill, “This is the perfect guy for Shaka.” And Bill didn’t want that, because he wanted an Englishman or an American to play Shaka. He said, “No,” because he saw that as a way of making himself more famous — by having a big name to play Shaka. And I said, “No, Shaka has to be Zulu. I promised that to the king. It has to be a Zulu. You can’t take anybody else but a Zulu. It would be an outrage for the Zulus to have Shaka played by an American or an Englishman.” Bill didn’t believe in that at all. He had done some documentaries for BOSS, which is the Bureau of State Security. So, that’s why I didn’t understand what his politics were. But he grabbed Shaka, because it was a good idea for him to do that. Then he started saying to people that he had had the idea of Shaka, which wasn’t true. My book came out long before Bill was even considered for that. In fact, originally, I was supposed to direct it. But I couldn’t, because of the cultural boycott.

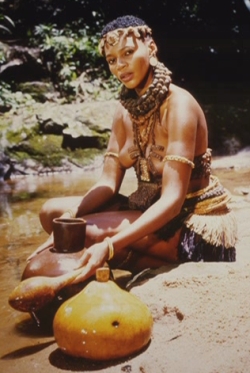

Anyway, Bill and I discussed [casting Henry], and Bill finally agreed. Then Dudu Mkhize, who played Nandi, I met through an Italian photographer in Johannesburg. He said, “I have the most beautiful woman in the world.” That was Dudu, and she is Nandi. She was a model. Henry was a football player. Zero acting experience.

But Henry was Zulu, and he became Shaka. You take an Arapaho, you take a Sioux, and you’re told, “You’re going to play this leader.” You become that, because it’s part of your heritage, and you don’t have to act for that. This is ready-made method acting. So, you play Shaka. It takes you a while, and you get into it, and all of the heritage. Because when I wrote the script, 70% of it I made up. But I didn’t make it up myself. I got it from people. I lived with the Zulus. I heard the Zulus. I listened to them. I threw stuff in myself. Shaka had never heard about Christ. The first  missionary to the Zulus was Reverend George Champion, who went to Dingane, who was the half-brother who killed Shaka. But Shaka himself had never heard about Christ. Henry Francis Fynn was not a doctor. He was Superintendent of Cargo. He didn’t know Christ from a hole in the head. Yes, he was an Irish Catholic. But I turned that into a big thing. Francis George Farewell was more or less the same as Farewell was. Although, I turned him into another sort of figure. So Fynn existed, but didn’t exist the way he did in my script. So I said, “As long as he’s Irish, and as long as he maybe is sort of a missionary and has a theological background, let’s get him involved.” I wanted to confront the “King of Kings” who has a standing army of 1 million, with the “King of Kings” that the Brits keep talking about — who died on a cross with nobody around, except a couple of women and an 18 year-old kid. This absurdity of our Christianity, of the entire Judeo-Christian origin of our civilization, is for a Zulu something which is very difficult to understand. That’s why I have at the end of Shaka, especially in the book, that he can’t understand who this man Jesus is that they keep talking about. I needed to bring that in — which he didn’t know about, but I needed to understand. Shaka was a very curious man. He had to be curious, because he created this incredible empire. He asked, “Is this the right weapon?” Then he invented the iklwa.

missionary to the Zulus was Reverend George Champion, who went to Dingane, who was the half-brother who killed Shaka. But Shaka himself had never heard about Christ. Henry Francis Fynn was not a doctor. He was Superintendent of Cargo. He didn’t know Christ from a hole in the head. Yes, he was an Irish Catholic. But I turned that into a big thing. Francis George Farewell was more or less the same as Farewell was. Although, I turned him into another sort of figure. So Fynn existed, but didn’t exist the way he did in my script. So I said, “As long as he’s Irish, and as long as he maybe is sort of a missionary and has a theological background, let’s get him involved.” I wanted to confront the “King of Kings” who has a standing army of 1 million, with the “King of Kings” that the Brits keep talking about — who died on a cross with nobody around, except a couple of women and an 18 year-old kid. This absurdity of our Christianity, of the entire Judeo-Christian origin of our civilization, is for a Zulu something which is very difficult to understand. That’s why I have at the end of Shaka, especially in the book, that he can’t understand who this man Jesus is that they keep talking about. I needed to bring that in — which he didn’t know about, but I needed to understand. Shaka was a very curious man. He had to be curious, because he created this incredible empire. He asked, “Is this the right weapon?” Then he invented the iklwa.

Shaka teaches his warriors new tactics, using the Iklwa — from Episode 6 of Shaka Zulu:

Shaka: “Strategy, speed, and physical contact. The leopard hunts, waiting for the best moment to strike. Next, he uses his speed to outrun the victim. And finally, physical contact, when he sinks his fangs into the impala’s throat. Our [current] strategy’s ludicrous. We go out of our way to make our presence known. And our warfare has no physical contact, and no close combat. In fact, we toss away our weapons, hoping that the enemy will be courteous enough to return them to us. Our strategy will come later. Let’s start with speed. Take off your sandals! In return for your dedication, I promise you glory. If anyone here feels that bruised feet are too high a price to pay for glory, he must say so now! Run!”

For me, Shaka’s greatest curiosity was “[Whites] come from all the way over there. Why? What are they doing here? What do they want from me? They want me to believe in this king who died on a cross, betrayed by his own disciples — who were, for the most part, unarmed? No army was there to help him?  Nobody? They just killed him? And that king is now the most powerful king in Europe? How? I’m a ruler. I’m a general. I’m the head of an army. They call me the ‘Inkosi ya makosi’, the King of Kings. Why is that King of Kings better than I am? Why do they want me to believe in that King of Kings? What is it about him?” Well, the secret of that King of Kings is forgiveness. Because you throw a rock, they throw a rock. They throw a rock, you throw a rock. And it goes on forever. The idea of truth has to come from forgiveness at some stage. Somebody has to say, “Enough.” As many people said, including Gandhi, “To reach out and shake the hand of a friend is easy. But to shake the hand of an enemy is almost impossible. But until you do that, you can’t find peace.”

Nobody? They just killed him? And that king is now the most powerful king in Europe? How? I’m a ruler. I’m a general. I’m the head of an army. They call me the ‘Inkosi ya makosi’, the King of Kings. Why is that King of Kings better than I am? Why do they want me to believe in that King of Kings? What is it about him?” Well, the secret of that King of Kings is forgiveness. Because you throw a rock, they throw a rock. They throw a rock, you throw a rock. And it goes on forever. The idea of truth has to come from forgiveness at some stage. Somebody has to say, “Enough.” As many people said, including Gandhi, “To reach out and shake the hand of a friend is easy. But to shake the hand of an enemy is almost impossible. But until you do that, you can’t find peace.”

Shaka confronts Nandi about hiding the birth of his son and heir — from Episode 8 of Shaka Zulu:

Shaka: “You have deceived me, just as you deceived my father. I have made you Queen of Queens. The most powerful woman in this land, in the world. But that was not enough for you, mother. You wanted more … Love. We are incapable of that emotion, mother. All that we feel, all we ever felt, is vengeance and hate… hate… hate! And I am the product of your hatred, just as [my son] is the product of my hatred.”

When Shaka’s mother died, there was a year of mourning. It was a catastrophe for him. So when I heard this, I said, “Well, he must have been very close to his mother.” Why? Then I got very Freudian. Most of that, I repeat, is made up. Because it’s not as if I have any proof of this. But now they teach it at university. So I must have figured out something right. I figured that if he was that close to his mother,  his father disowned him in a way. Shaka means “beetle.” When Nandi came and presented herself to Senzangakhona and said, “I’m pregnant with your child,” they weren’t married. Of course, he could have many wives, but she wanted to be his principle wife. This is a woman with balls. He laughed at her and said, as they said then in Africa, “You suffer from the disease of the beetle.” Because if you were stung by a beetle, you sometimes would miss your period. And in Zulu, beetle is “shaka.” So he says, “You have the disease of the shaka.” So she comes back nine months later and says, “Here’s your Shaka.” And that’s where the name comes from. The whole scene [of baby Shaka’s presentation], where they go back and forth bargaining the number of cattle, that’s called “lobola“. Usually a woman would not do it herself. The elders would do it.

his father disowned him in a way. Shaka means “beetle.” When Nandi came and presented herself to Senzangakhona and said, “I’m pregnant with your child,” they weren’t married. Of course, he could have many wives, but she wanted to be his principle wife. This is a woman with balls. He laughed at her and said, as they said then in Africa, “You suffer from the disease of the beetle.” Because if you were stung by a beetle, you sometimes would miss your period. And in Zulu, beetle is “shaka.” So he says, “You have the disease of the shaka.” So she comes back nine months later and says, “Here’s your Shaka.” And that’s where the name comes from. The whole scene [of baby Shaka’s presentation], where they go back and forth bargaining the number of cattle, that’s called “lobola“. Usually a woman would not do it herself. The elders would do it.

How did Edward Fox and Robert Powell come to be in Shaka Zulu?

Fox and Powell came to the project because they loved the screenplay. I said to Powell, “Look, you realize there’s a cultural boycott. I personally cannot return to South Africa. Are you going to do it?” And I remember Powell looked me in the eye and said, “I’m going there because the script you wrote is just too damn good.” I didn’t know what to say about that. I had James Earl Jones to play Dingiswayo — just as Martin Sheen was supposed to play Fynn. But then they didn’t, because of the cultural boycott. Powell and Fox did it. And not because they didn’t care about apartheid. You see, another aspect [of participating] was to believe that by doing Shaka, and making it such a big thing, it would explode out of South Africa, and the regime would be forced to accept Shaka as one of their heroes. And by doing so, they would have to accept the fact that the Blacks could have heroes at all. And that’s what happened, in fact.

Fox and Powell came to the project because they loved the screenplay. I said to Powell, “Look, you realize there’s a cultural boycott. I personally cannot return to South Africa. Are you going to do it?” And I remember Powell looked me in the eye and said, “I’m going there because the script you wrote is just too damn good.” I didn’t know what to say about that. I had James Earl Jones to play Dingiswayo — just as Martin Sheen was supposed to play Fynn. But then they didn’t, because of the cultural boycott. Powell and Fox did it. And not because they didn’t care about apartheid. You see, another aspect [of participating] was to believe that by doing Shaka, and making it such a big thing, it would explode out of South Africa, and the regime would be forced to accept Shaka as one of their heroes. And by doing so, they would have to accept the fact that the Blacks could have heroes at all. And that’s what happened, in fact.

Fox also loved the adventure. He loved the fact that it meant shooting in South Africa, which is such a beautiful place. He thoroughly enjoyed the role, and was having a ball. I think it’s one of the few roles in his life where he actually enjoyed himself that much. That’s why his brother, James later played Farewell in Shaka 2. Fox is an adventurer. They both are. But especially Edward.

He liked working with Alec Mills, the director of photography. And it was fun. It was horseback. It was a ship at sea. It was dressing up like a Zulu. All sorts of things were in that. There’s so much in Shaka Zulu, that a guy like Fox thought, “This is so out of the box. It’s great!” The same thing that Trevor Howard felt.

What was your approach portraying Roy Dotrice‘s George IV in the opening episode of Shaka?

That was something I directed myself with him in London. George IV as prince regent was actually rather fat, and maybe gay, maybe not gay. Who really cares. Everybody was something in those days. Especially in France, where they were a little bit of everything — and especially Louis XV. I think Louis XV was probably the most promiscuous king in the history of mankind. But George IV was a close second. Especially since he had free reign, considering his father was mad. Now, when you write something like this, you’re not thinking of an actor. Often I do. But in this case, I didn’t. I thought, “I’m gonna make him camp.” In other words, the absurdity for an English king to have to worry about the Zulus, when his father had lost half the empire in America with the Revolutionary War. This is a couple of decades after it. Henry Bathurst was the Secretary of the Colonies, and he comes to George IV as somebody as great as Christopher Lee, and with his wonderful English says:

That was something I directed myself with him in London. George IV as prince regent was actually rather fat, and maybe gay, maybe not gay. Who really cares. Everybody was something in those days. Especially in France, where they were a little bit of everything — and especially Louis XV. I think Louis XV was probably the most promiscuous king in the history of mankind. But George IV was a close second. Especially since he had free reign, considering his father was mad. Now, when you write something like this, you’re not thinking of an actor. Often I do. But in this case, I didn’t. I thought, “I’m gonna make him camp.” In other words, the absurdity for an English king to have to worry about the Zulus, when his father had lost half the empire in America with the Revolutionary War. This is a couple of decades after it. Henry Bathurst was the Secretary of the Colonies, and he comes to George IV as somebody as great as Christopher Lee, and with his wonderful English says:

Bathurst: “It is Africa, I’m afraid, sir. I have received a most alarming missive from Lord Somerset at the Cape. It concerns the Zulus, sir.”

George IV: “The Zulus? Are you implying that the Colonial Office of the British Empire considers a tribe of savages running around in their birthday suits a problem? Oh, really. What ineffable twaddle, Lord Henry.”

Bathurst: “It is somewhat more than a tribe, sir. We are convinced that we are at grips with a proper empire of a quarter of a million such birthday suits.”

George IV: “Really? My, my. They do multiply, don’t they… like bunnies.”

Bathurst: “Your majesty, it is possible that the Zulus will attack the Cape. If that should happen, we would have to deal with a very large number of these bunnies, under the leadership of a March hare by the name of Shaka.”

I loved writing that dialogue. I really adored that relationship. When George IV goes to the window, and he says, “Look out there, Bathurst. What do you see… falling?” And Bathurst says, “Rain, your majesty.” And George says, “And what is your job?” You know, the idea of bringing sunshine to a country where it always rains. And if you can’t bring sunshine to a country where it always rains, he’ll find somebody who can bring sunshine. That scene, when I wrote it, was so absurd that  I said, “I don’t know if I’m going to get away with a scene like this. Because this is the prince regent. I’m making fun of the English.” But in a way, they were like that. And I already set him up as a lush at the beginning of the scene. If you read the original screenplay, he was set up as a lush, eating the grapes, with the women around him. I was really thinking of Louis XV. But George IV was the same. It was a time when people were that spoiled. I started with Bathurst in the waiting room — waiting, and waiting, and waiting. This man, you never know when he gets up. Then someone emerges with, “His majesty has risen.” It’s so absurd in today’s world. But it really happened. And I wanted to have that whole feel to it, which is different from Victoria. Because Victoria was staunch. George IV was nuts. They were all nuts. His father was really nuts, and he was just as nuts. So for somebody to come out and tell everybody that his majesty has finally gotten up in the middle of a day — where do you go from there when you’re the writer? How do you then open those doors, and actually present this man? You’ve got to present someone who is obviously sleeping as long as he wants to, who is

I said, “I don’t know if I’m going to get away with a scene like this. Because this is the prince regent. I’m making fun of the English.” But in a way, they were like that. And I already set him up as a lush at the beginning of the scene. If you read the original screenplay, he was set up as a lush, eating the grapes, with the women around him. I was really thinking of Louis XV. But George IV was the same. It was a time when people were that spoiled. I started with Bathurst in the waiting room — waiting, and waiting, and waiting. This man, you never know when he gets up. Then someone emerges with, “His majesty has risen.” It’s so absurd in today’s world. But it really happened. And I wanted to have that whole feel to it, which is different from Victoria. Because Victoria was staunch. George IV was nuts. They were all nuts. His father was really nuts, and he was just as nuts. So for somebody to come out and tell everybody that his majesty has finally gotten up in the middle of a day — where do you go from there when you’re the writer? How do you then open those doors, and actually present this man? You’ve got to present someone who is obviously sleeping as long as he wants to, who is  a lush. Good. So that’s the way I showed him. How does a man like that take the idea that Bathurst is there to tell him? “We have a problem with the Zulus.” Remember, we’re talking about Shaka more than 25 years after it was shown. When I was writing Shaka, people didn’t really even know who the Zulus were. People didn’t know the name Shaka. The Zulus were probably the most interesting tribe in Africa, next to the Maasai. But in Europe and the States, people didn’t really know that much about the Zulus — and they’d certainly never heard of Shaka. Now Shaka has become important, because [Shaka Zulu] has been shown so many times on television. But back when I was writing it, he wasn’t important. And in the days of George IV, he was even less important. The Zulus were “The who?” Later, the Zulus were the first colonial army to defeat England ever [at the Battle of Isandlwana]. Zulu was a fabulous film. Not just the acting, which was fabulous. But the way the Zulus [fought at the Battle of Rorke’s Drift] is shown so well in that film. They understood the rifle, and that it had to reload. They figured that it would take 3-4 seconds for a good Brit to reload. But they had expendable armies. So they said, “We’ll send one row forward to die.” That’s the way the Zulus were. “The next will be so fast, that we’ll be on top of them.” The Brits would never think that they would send 1,000 men to die. And behind them were the guys that were going to kill you.

a lush. Good. So that’s the way I showed him. How does a man like that take the idea that Bathurst is there to tell him? “We have a problem with the Zulus.” Remember, we’re talking about Shaka more than 25 years after it was shown. When I was writing Shaka, people didn’t really even know who the Zulus were. People didn’t know the name Shaka. The Zulus were probably the most interesting tribe in Africa, next to the Maasai. But in Europe and the States, people didn’t really know that much about the Zulus — and they’d certainly never heard of Shaka. Now Shaka has become important, because [Shaka Zulu] has been shown so many times on television. But back when I was writing it, he wasn’t important. And in the days of George IV, he was even less important. The Zulus were “The who?” Later, the Zulus were the first colonial army to defeat England ever [at the Battle of Isandlwana]. Zulu was a fabulous film. Not just the acting, which was fabulous. But the way the Zulus [fought at the Battle of Rorke’s Drift] is shown so well in that film. They understood the rifle, and that it had to reload. They figured that it would take 3-4 seconds for a good Brit to reload. But they had expendable armies. So they said, “We’ll send one row forward to die.” That’s the way the Zulus were. “The next will be so fast, that we’ll be on top of them.” The Brits would never think that they would send 1,000 men to die. And behind them were the guys that were going to kill you.

I saw Christopher Lee 2-3 years ago. I went to the Vienna Filmball, and I hadn’t seen him in maybe 15 years. Because I saw him a bit after Shaka too. I went to the Filmball, and I sat at the same table with him and with Maximilian Schell. I looked across at him, and I said, “Hello, Christopher.” And he said, “I know you.” And I said, “Yebo, baba.” And he said, “Shaka!” He got up, old Chris with his cane, and came hobbling around. I said, “No, no, I come to you.” And he says, “No, no, I come to you, inkosi.” Which means “king”. And it was a funny thing, because it was the Viennese Filmball, and the two of us were sitting there speaking Zulu. And nobody in the universe expected Christopher Lee of Hammer Films, and all the stuff that he’s done, to be sitting next to me speaking Zulu.

Why did you include Queen Victoria, and Shaka’s heirs losing the empire in the Anglo-Zulu War?

When the Zulus became the first to defeat Great Britain and the empire, this was a big letdown for guys like Cecil Rhodes, who was born racist. Remember that in those days, if you read the old books from the 1800s, like The Life of Sir Richard Burton — Isabel his wife, who wrote the biography, says “That Great Imperialist, Richard.” To be an imperialist in those days was a compliment. Nowadays, it’s not. In fact, if you still talk to some Brits from the older generation, in their 80s — and I do all the time — they still think it’s great to be an imperialist. The empire of Queen Victoria was important.

Prof. Bramston’s report to Queen Victoria, given August 1882 at the end of “the Zulu Wars” — from Episode 1 of Shaka Zulu:

Prof. Bramston: “Shaka Zulu, your majesty. Yes, the founder of the greater Zulu nation and the Zulu Empire reigned from 1816 to 1828. Most definitely one of the greatest military geniuses in history, and certainly on the level of a Caesar or an Alexander the Great. Imagine, if you will, the prodigious feat accomplished by this 19th Century African Achilles, Shaka Zulu. In less than 12 years he transformed a handful of idyllic relatively harmless herdsmen, who were by nature reluctant to engage in any form of warfare, into a Spartan army of over 80,000 highly-trained ruthless warriors, extending his influence over most of Southeast Africa. An empire comparable in extension and might to that of Napoleon, and in treachery to that of Genghis Khan. Your majesty, gentlemen, the war machine created by Shaka Zulu was so monolithic, it has survived his death by almost half a century. Yes, yes, the crown has now defeated it. But that defeat is purely temporary. It can and will rise again and again if we do not stop it once and for all. And why? Because King Shaka was no ordinary mortal. He was a messiah. A god figure. Like an African Mephistopheles, he gave the Zulus glory, in return for their souls. Wielding the forces of life and death on an endless battlefield of blood and carnage…”

What sort of reactions did you get to writing Shaka Zulu?

There were some people in South Africa who were angry with me, because I had done something they didn’t do. I’m talking about Zulus. And when they saw me, they said, “Why did you do something that we should have been doing?” And I said, “I don’t know, why didn’t you do it? I didn’t stop you. I was minding my own business, and you came and asked me to do this.” But then we got over it.

I went to the Elton John Oscars party, because Grace Jones was in Shaka 2. And Chaka Khan was there and said, “You wrote Shaka Zulu?” She was jumping up and down. I meet basketball players whose names are Shaka. I meet all kinds of people whose names are Shaka. When I wrote this, nobody had even heard of Shaka. There were no Shakas anywhere. Suddenly there are Shakas all over the place. So the reception was, “Finally, a mythological thing which could identify the proud  heritage of the African-Americans.” Wrong. It’s a proud heritage of people when you reach a stage where you are colorblind. I did not want to show that those Africans that became slaves later had a great heritage. We know that. I wanted to show that nobody should be slaves — whether they’re Jews or Africans or Iroquois. Because the Sioux did not have a proud heritage? Of course they did. But are great movies made like that? In fact, somebody asked me to do a movie about that. My mother was blood sister to Chief Walking Buffalo of the Blackfoot Indians of Alberta. So when I was growing up, all we heard about were the Cherokees. They would come and visit. And to me, it was very important that we understand that what we did wrong — we, meaning Europe — is to not listen to these people. We wiped out the Cherokee before they had a chance to even say, “Hello.” We took it for granted that they had no culture. The Aztec, the Maya — we took it for granted that we had something to teach them, and we had nothing to learn. It’s the same with Africa. We never really listened to the African. We went there thinking that Christ was the currency — as I wrote in Shaka — with which we bought the land, the birthright, and the freedom of the African. We use Christ as a currency. We’ll give you Christ, you give us the land. As [Jomo] Kenyatta says, “They gave us bibles, told us to close our eyes, and to pray. And when we opened our eyes, we had their bibles, and they had our land.” It was all wrong.

heritage of the African-Americans.” Wrong. It’s a proud heritage of people when you reach a stage where you are colorblind. I did not want to show that those Africans that became slaves later had a great heritage. We know that. I wanted to show that nobody should be slaves — whether they’re Jews or Africans or Iroquois. Because the Sioux did not have a proud heritage? Of course they did. But are great movies made like that? In fact, somebody asked me to do a movie about that. My mother was blood sister to Chief Walking Buffalo of the Blackfoot Indians of Alberta. So when I was growing up, all we heard about were the Cherokees. They would come and visit. And to me, it was very important that we understand that what we did wrong — we, meaning Europe — is to not listen to these people. We wiped out the Cherokee before they had a chance to even say, “Hello.” We took it for granted that they had no culture. The Aztec, the Maya — we took it for granted that we had something to teach them, and we had nothing to learn. It’s the same with Africa. We never really listened to the African. We went there thinking that Christ was the currency — as I wrote in Shaka — with which we bought the land, the birthright, and the freedom of the African. We use Christ as a currency. We’ll give you Christ, you give us the land. As [Jomo] Kenyatta says, “They gave us bibles, told us to close our eyes, and to pray. And when we opened our eyes, we had their bibles, and they had our land.” It was all wrong.

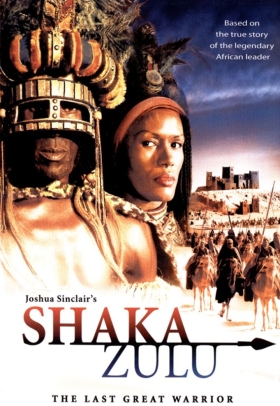

How did your second Shaka film come about?

They asked me in South Africa to do another one. So, I started writing it. Then I ended up going into slavery, because I wanted to show slavery. Then we shot part of it in South Africa, but I wanted it to be pan-African. So part in South Africa, part in Morocco, with extras from Mali. In fact, Ridley Scott was shooting Gladiator at the time. Scott and I would exchange the really great-looking Mali extras. He wanted them for gladiators, and I wanted them for Zulus. So it had to be pan-African. It had to be something bigger.

They asked me in South Africa to do another one. So, I started writing it. Then I ended up going into slavery, because I wanted to show slavery. Then we shot part of it in South Africa, but I wanted it to be pan-African. So part in South Africa, part in Morocco, with extras from Mali. In fact, Ridley Scott was shooting Gladiator at the time. Scott and I would exchange the really great-looking Mali extras. He wanted them for gladiators, and I wanted them for Zulus. So it had to be pan-African. It had to be something bigger.

The second one is not really a sequel, because I created the adventure of the slave ship. And the 90-minute cut in the States is not the way it should be. It should be 180 minutes. I shot it to be 180 minutes, and my script was 180 minutes. That’s the way it’s conceived. You can’t take a 180-minute movie, or a two-part TV series, and chop it down to 90 minutes. It’s a totally different movie. The first Shaka, I wrote 13 hours. So it was always supposed to be [a final cut of] about 5 or 6 hours. Then there were various versions of it that came out, because there were politics behind it.

When I did the first Shaka, there was just so much [violence and gore] I could do on television. I didn’t even expect the nudity to fly, but it did. And that was racist on the part of America, and the rest of the world. Because its OK to show a Black woman’s breasts, but you can’t show a White woman’s breasts.

One other thing they did [for Shaka 2‘s U.S. release] was to pick out a lot of the White bits, and keep in the Black bits. Even on the cover, it’s Grace and Henry. But it’s not about selling to the Black community. This is about showing that we’re colorblind. But if you’re going in that direction, then you’re showing that you’re not colorblind. You’re showing that you’re manipulative.

The idea of Shaka 2 was “What if we take the most powerful man in Africa, and put him on a slave ship? Would he come out of the slave ship and kill everything White? Or could he find forgiveness?” I didn’t want Shaka 2 to be confused with the first Shaka. Because it was more mythological. It was more of a study on what would happen if a great warrior like Shaka saw what the slave ships were like.

I want people to understand that the first Shaka was 70% fiction, in the sense that I made it up in my book. But the novel was based on tradition. It had the spirit of Zulu. That’s why it’s still being sold on Amazon, and it’s still considered to be Shaka. The problem is that the first one seemed so right to everybody, that they invited me sometimes to Zululand University to talk about Shaka as an historical piece — or even UCLA. Mazisi Kunene wrote a book called Emperor Shaka the Great, years ago. I went to the African Studies department once at UCLA, and said, “Remember with Shaka, 70% of it I made up.” Now here I stand, White, not South African. And they’re looking at me like, “What?!” That was a terrible thing to do. Mazisi said, “Stop saying that.” I said, “Well, it’s the truth.” And he said, “Well, stop saying that. This is our heritage.” I said, “No, it’s not your heritage. It’s universal heritage. I’m tapping into the collective unconscious.” And if you tap into the collective unconscious, you find the myth in everything.

In Shaka Zulu, there was a metaphysical dimension. But the metaphysical dimension was not Shaka. In all the great movies now, where there are superheroes, the metaphysical dimension is always the guy with the nice shiny shield, or the guy who can kill the most men. That’s the metaphysical dimension. You reach the level of myth. Shaka never became a myth in his own lifetime. He never saw himself as a myth. He never saw himself as immortal. In the book especially, he’s always worried about death. Because every warrior has to worry about death, right? So there’s nothing today that allows the warrior to be a warrior, and appeal to a greater power. The greater power is him. Then Hollywood comes up with all these weird forces of evil, and good, and dragons, trying to reach that metaphysical dimension. For Shaka, it was simple. “There’s one Inkosi ya makosi, and I’m the other Inkosi ya makosi. One of us has to win.” But the “other” is metaphysical. So how can you fight the metaphysical? You can’t, because you can’t even hold onto it.

In Shaka Zulu, there was a metaphysical dimension. But the metaphysical dimension was not Shaka. In all the great movies now, where there are superheroes, the metaphysical dimension is always the guy with the nice shiny shield, or the guy who can kill the most men. That’s the metaphysical dimension. You reach the level of myth. Shaka never became a myth in his own lifetime. He never saw himself as a myth. He never saw himself as immortal. In the book especially, he’s always worried about death. Because every warrior has to worry about death, right? So there’s nothing today that allows the warrior to be a warrior, and appeal to a greater power. The greater power is him. Then Hollywood comes up with all these weird forces of evil, and good, and dragons, trying to reach that metaphysical dimension. For Shaka, it was simple. “There’s one Inkosi ya makosi, and I’m the other Inkosi ya makosi. One of us has to win.” But the “other” is metaphysical. So how can you fight the metaphysical? You can’t, because you can’t even hold onto it.

I talked to SABC a little bit about Shaka 2. But everybody had changed at SABC. There were totally different people. I also talked to M-Net, but they didn’t really understand why I had Shaka on a slave ship. “He’s too good to be on a slave ship.” And I said, “Are you telling me that Christ was too good to be on a cross?” Sometimes people have to suffer in order to reach a point of forgiveness. So all the martyrs of various faiths have had to suffer in order to understand the meaning of suffering. So it wasn’t what SABC wanted, and they were afraid that my Shaka 2 would hurt their Shaka 1. And I said, “It can’t, because they’re both based on my book.”

What was your take on the now-removed statue of an unarmed Shaka at Durban airport?

The agenda behind that was that the image of Shaka in the minds of the people should be a unifying image of peace, and not an image that would be against the government of Pretoria, or against any other tribe. This is not the Shaka that started the empires and the mass displacement of peoples, which goes back to the 1820s. This is the Shaka that they remember as the Shaka who was also a bit of a poet, who united the Zulu people into a kingdom called KwaZulu-Natal. He was whitewashed. By  showing Shaka without the iklwa, he became a little too peaceful. The iklwa is called that because it’s onamonapia. That’s the sound it makes when you pull it out of a person’s body. Shaka created the iklwa, because before that they threw the spears. So he made the spear head bigger, and he made the haft smaller, and you hold it like a sword. To show Shaka without a spear is a bit strange, because he was above all a warrior king. It’s a little like showing Alexander the Great without a sword, or the statue of Nelson without a gun. You don’t. I mean, these are warriors. George Washington was basically a general. Even though he was a farmer. He didn’t want to be a general. But he was a general, and he was pretty good at it. Then he didn’t want to be President. But he was President, and he was pretty good at it. So nobody really knew what to do with him. So now he’s turned into this rather meek person who says, “Yes, I chopped down the cherry tree.” People keep trying to figure out who he was and what he was. Now, Shaka’s different.

showing Shaka without the iklwa, he became a little too peaceful. The iklwa is called that because it’s onamonapia. That’s the sound it makes when you pull it out of a person’s body. Shaka created the iklwa, because before that they threw the spears. So he made the spear head bigger, and he made the haft smaller, and you hold it like a sword. To show Shaka without a spear is a bit strange, because he was above all a warrior king. It’s a little like showing Alexander the Great without a sword, or the statue of Nelson without a gun. You don’t. I mean, these are warriors. George Washington was basically a general. Even though he was a farmer. He didn’t want to be a general. But he was a general, and he was pretty good at it. Then he didn’t want to be President. But he was President, and he was pretty good at it. So nobody really knew what to do with him. So now he’s turned into this rather meek person who says, “Yes, I chopped down the cherry tree.” People keep trying to figure out who he was and what he was. Now, Shaka’s different.

King Dingiswayo reprimands Shaka, the general of his armies, over the latter’s brutal tactics — from Episode 6: of Shaka Zulu:

Dingiswayo: “I wanted the name ‘Mthethwa’ to stand for peace! Not total war! I wanted my armies to bring subjugation! Not destruction!”

Shaka: “To subdue another tribe, you must strike it once and for all. Total war. Total subjugation to the paramount king, and total destruction to anyone who raises even a whisper against him. Never leave an enemy behind, or it will rise again to fly at your throat. There’s no other way!”

Shaka really was a cutthroat — in the sense that it was war. He brought war to South Africa. Real war, where there are no holds barred and all is fair. Before that, war was more of a game. Yes, you would get  hurt. But it was a contest to see which side was stronger, and which side could sing louder, and stamp their feet harder, and make more noise. That side would win. It was like a football game. You don’t expect in a football game for the quarterback to throw a bomb, instead of a football. But Shaka took the football out of the quarterback’s hand, and put a grenade into it. So now he was throwing a grenade at the enemy. So it doesn’t really make sense to show Shaka without that. Because that’s what unified KwaZulu-Natal: War. Yes, he tried to make peace in the paramountcy. He kept meeting with leaders of the other tribes to try to find a peaceful resolution, because he also didn’t want everybody to be killed. But nobody could do or say anything to Shaka that he didn’t like, and get away with it.

hurt. But it was a contest to see which side was stronger, and which side could sing louder, and stamp their feet harder, and make more noise. That side would win. It was like a football game. You don’t expect in a football game for the quarterback to throw a bomb, instead of a football. But Shaka took the football out of the quarterback’s hand, and put a grenade into it. So now he was throwing a grenade at the enemy. So it doesn’t really make sense to show Shaka without that. Because that’s what unified KwaZulu-Natal: War. Yes, he tried to make peace in the paramountcy. He kept meeting with leaders of the other tribes to try to find a peaceful resolution, because he also didn’t want everybody to be killed. But nobody could do or say anything to Shaka that he didn’t like, and get away with it.

Shaka orders two childhood tormenters to be impaled to death in front of their king, Makedama — from Episode 6 of Shaka Zulu:

Shaka: “You disapprove of me, Makedama?”

Makedama: “No, Shaka. I disapprove of the great Sigidi. The man who fights like a million.”

Shaka: “You were kind to my mother and me. And I won’t forget that. I’ll not kill you, or your people.”