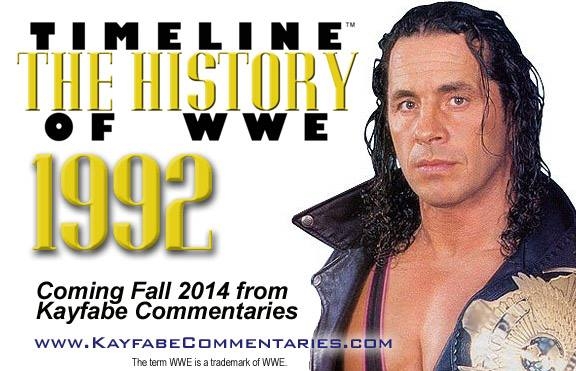

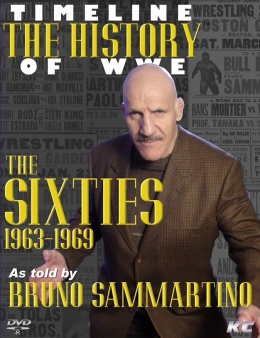

Who: Sean Oliver is the co-founder of Kayfabe Commentaries, which produces interviews with professional wrestlers (and others in the industry) about the history of their business. Oliver conducts the interviews, and produces them in a variety of styles. Perhaps the most ambitious of these is the “Timeline” series (covering the WWE, the WCW and the ECW) in which interviewees expound on their views of a specific year’s events. Past Timelines have included Kevin Nash on the WWE in 1995, Jim Cornette on the WWE in 1997, and Vince Russo on the WCW in 2000. In 2013, Oliver scored a crucial interview with wrestling legend Bruno Sammartino on the WWE in 1963-69. 2014 is set to build on that with a series of big-name legends, including the just-released Vader on the WCW in 1993, and upcoming interviews with “Rowdy” Roddy Piper and Bret “The Hitman” Hart.

Who: Sean Oliver is the co-founder of Kayfabe Commentaries, which produces interviews with professional wrestlers (and others in the industry) about the history of their business. Oliver conducts the interviews, and produces them in a variety of styles. Perhaps the most ambitious of these is the “Timeline” series (covering the WWE, the WCW and the ECW) in which interviewees expound on their views of a specific year’s events. Past Timelines have included Kevin Nash on the WWE in 1995, Jim Cornette on the WWE in 1997, and Vince Russo on the WCW in 2000. In 2013, Oliver scored a crucial interview with wrestling legend Bruno Sammartino on the WWE in 1963-69. 2014 is set to build on that with a series of big-name legends, including the just-released Vader on the WCW in 1993, and upcoming interviews with “Rowdy” Roddy Piper and Bret “The Hitman” Hart.

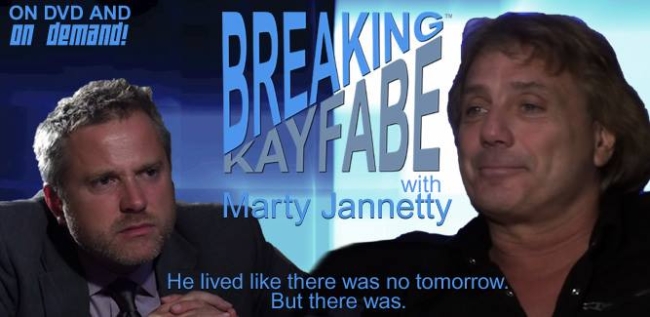

Kayfabe Commentaries also produces the interactive, and often-comedic, YouShoot — where interviewees answer questions from fans. Yet another series is the more-serious Breaking Kayfabe, which delves into the personal lives of wrestling stars. Among those Oliver talked to was Lanny Poffo — son of Angelo Poffo, and younger brother of “Macho Man” Randy Savage. Poffo gave incite into the brilliant career and complicated psyche of his brother, who died in 2011 without giving an in-depth interview on those topics. Camera In The Sun spoke with Oliver about Kayfabe Commentaries, some of his memorable interviews, and his take on the cultural aspects and impacts of pro wrestling.

How did you become a wrestling fan, and then start Kayfabe Commentaries?

I was a fan as a child, and I kind of fell out of touch with it in the ’90s. I guess either my maturation, or the lack of maturation of a lot of the storylines and angles in the business kind of put us on an opposite course. But I always kept an eye on it. Growing up when I did — I’m 41 — they were our real-life superheroes. So as a kid, it was very easy to get lost in that aspect of it. Years later, my business partner and I came upon the concept of doing alternate audio commentaries for wrestling matches — akin to a DVD, where there’s an alternate audio commentary with the director, telling you how a shot was set up or the rehearsal process with an actor for a scene.  We thought that if you bring the talent in, I would sit on headset with them, and have them go through all the matches we had seen historically for years and years. But here would be a new wrinkle, because the talent would be walking you through it. Now of course we couldn’t sell the video of the matches. We didn’t own the license to the video. But we were selling the downloadable MP3s of alternate commentaries for wrestling matches — an idea which I still think can see its day. I think it would be interesting to sit with a headset on, watch Game 7 of the 1987 NBA Finals, and listen to Larry Bird tell you about the game as you watch it. So you put the match on, you put your iPod on, and you listen to our commentary track with your TV muted. That was the pitch. Kind of a high concept. So it was a little slow for people to adapt. But the wrestling fans that liked it, really enjoyed the inside track that they were getting. So that was the gold that we struck, but realized that it had to be repackaged as something a little simpler. Something less of a process than downloading this, putting it on your iPod, muting your TV, finding the match. So that’s when we veered off into video, and decided to produce exclusively video content from that point on. But that was the genesis of it. Downloadable commentary tracks.

We thought that if you bring the talent in, I would sit on headset with them, and have them go through all the matches we had seen historically for years and years. But here would be a new wrinkle, because the talent would be walking you through it. Now of course we couldn’t sell the video of the matches. We didn’t own the license to the video. But we were selling the downloadable MP3s of alternate commentaries for wrestling matches — an idea which I still think can see its day. I think it would be interesting to sit with a headset on, watch Game 7 of the 1987 NBA Finals, and listen to Larry Bird tell you about the game as you watch it. So you put the match on, you put your iPod on, and you listen to our commentary track with your TV muted. That was the pitch. Kind of a high concept. So it was a little slow for people to adapt. But the wrestling fans that liked it, really enjoyed the inside track that they were getting. So that was the gold that we struck, but realized that it had to be repackaged as something a little simpler. Something less of a process than downloading this, putting it on your iPod, muting your TV, finding the match. So that’s when we veered off into video, and decided to produce exclusively video content from that point on. But that was the genesis of it. Downloadable commentary tracks.

What was it like watching Bruno Sammartino wrestle, and then working with him for KC?

I grew up in New Jersey, so I was a product of the Vince McMahon Sr. wrestling product on WWOR-TV Channel 9 on Saturday mornings with Superstar Billy Graham and Bruno Sammartino. My first live match was October 1981. The main event was Bruno Sammartino’s retirement match against George “the Animal” Steele. It was October of 1981 at the then-brand-new Meadowlands Arena, or “Brendan Byrne Arena”, in New Jersey.

In 2008 we produced a show, which was part of our Investigative Specials series, called “The Great Debate.” It was during the 2008 presidential debates. We had this crazy idea, and said, “What if we brought Bruno Sammartino in, and Harley Race in — two of the most iconic elder statesmen that are still with us, for the NWA and WWWF respectively — set up a podium, ask general wrestling questions that each could riff on for a while, and have a presidential-style debate?” That was the first time we worked with Bruno. Now, since then, we’ve  launched Timeline: The History of WWE. And it was going to be impossible for us to ever call that series complete without Bruno covering the Bruno years. There’s nobody else that could cover that portion of the WWE’s history. When we come up with a year, and we look to get somebody to sit with me for that particular year, there are usually some options. There’s a few people we can go for. But anything covering Bruno’s time had to be told by him. So we reached out, and we locked that up. And right afterwards, he accepted the offer to go into the WWE Hall of Fame. As we prepared to shoot, there were scheduling conflicts, and it got put off and put off. Finally, when Bruno went up to sign some paperwork, or something related to their Legends deal, they wanted exclusivity with his projects. But he still had that outstanding commitment to us. And Bruno, as testament to these old-school guys of wrestling years past, said to them in “Titan Tower” in Connecticut, “There is one company that I owe a show to.” And as he tells me, they kind of hemmed and hawed. But he was firm on that, and got them to make the exclusion for us to do that show.

launched Timeline: The History of WWE. And it was going to be impossible for us to ever call that series complete without Bruno covering the Bruno years. There’s nobody else that could cover that portion of the WWE’s history. When we come up with a year, and we look to get somebody to sit with me for that particular year, there are usually some options. There’s a few people we can go for. But anything covering Bruno’s time had to be told by him. So we reached out, and we locked that up. And right afterwards, he accepted the offer to go into the WWE Hall of Fame. As we prepared to shoot, there were scheduling conflicts, and it got put off and put off. Finally, when Bruno went up to sign some paperwork, or something related to their Legends deal, they wanted exclusivity with his projects. But he still had that outstanding commitment to us. And Bruno, as testament to these old-school guys of wrestling years past, said to them in “Titan Tower” in Connecticut, “There is one company that I owe a show to.” And as he tells me, they kind of hemmed and hawed. But he was firm on that, and got them to make the exclusion for us to do that show.

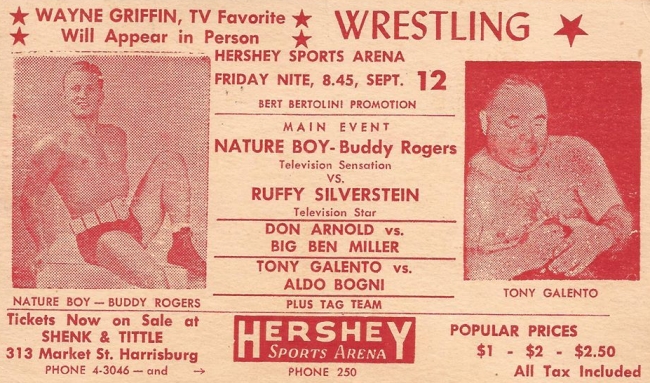

Bruno’s importance to the business is akin to Hulk Hogan‘s importance to the business circa 1983-4. He became the business. One of these people whose popularity and iconic status supplanted anybody else on the card. It didn’t even matter who Bruno was wrestling, or who Hogan was wrestling that night. Because Hogan was coming to town, Bruno was coming to town. Particularly in the Northeast, all these largely-ethnic areas of Boston, New York and Philadelphia. This was Bruno’s footprint. And you hear the stories all the time — they’ve become kind of comical anecdotes — of people crying when Bruno would lose. But there’s something so significant in those stories. Especially today, when I think people watch wrestling for spectacle — for the explosion, so to speak — and they’re not emotionally invested. About as much emotion that they have invested is the “ooh” and the “ahh” of the roller coaster. But Bruno would move people to tears, and that kind of passion is gone.

Is the championship belt still as important as it was in Bruno’s era?

For guys our age, this seems elementary, because it’s what we grew up seeing. The title meant something. When you watched a title change hands, it was a hugely significant event. It no longer is. The base fact that the frequency of title changes has increased so much is the largest commentary on why it doesn’t have significance. Because it happens all the time. And if it’s going to happen all the time, you can’t have the same people winning it all the time. Although, you do have like 16-time titleholders, which is asinine. You know, they’re 35 years old, and they’re 16-time title champions for the WWE. The title gets moved around the locker room a lot. So you’ve got half your roster that has held a title, each for 3-4 months at a time. You’d be foolish to think that it wouldn’t devalue a belt. I think the championship is little more than a prop in the storytelling. I guess it always was. But it was a much, much, much more significant prop prior, and carried much more weight in years past.

Today there’s so much product. Every week, the WWE cranks through however many hours of TV. It’s a lot. So it’s largely disposable viewing. It’s on, and then you’ve gotta forget it. Because two nights later, there’s gonna be something else that’s gonna advance that angle. And then two nights after that, something’s gonna advance that angle. There’s nothing to rewatch from a week ago, because it’s outdated by a week. Anything today that I rewatch on the internet, or on their on-demand channel, is largely from a nostalgic standpoint. I’m usually admiring the quality of the business at the time of the match I’m watching, and comparing it to how it’s absent now. Guys that were very gifted on the microphone, these guys were speaking from the gut. The words were their own. So there was that natural sincerity. Now, had nobody seen their scripting or their lines, they would struggle to deliver them with sincerity. So that’s the kind of stuff I look at when I watch it now.

What’s your view on forging a career as professional wrestler?”

I have the utmost respect for the majority of the people I interview who had to make a conscious decision at some point in their life to go on the road, to live out of a suitcase — largely with no guarantee of anything but the few bookings ahead of you, and where to go and who to wrestle. No guarantee on what your money’s gonna be. It’s all dependent on who shows up that night. If there’s a blizzard or a hurricane, that gets affected. Guys would go from territory to territory that way, and work in Florida for six months, New York for six months, Los Angeles for six months. The time when most of these guys that I interview came up, there weren’t these huge guaranteed contracts, and tie-ins with merchandise and all this stuff.

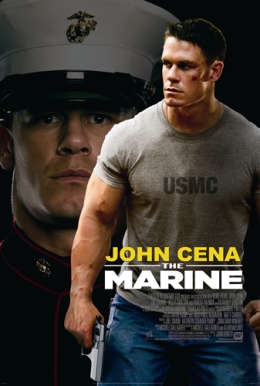

Nowadays, if you get a contract with WWE, you’re home-free for a while. You were never home-free back then. What made you home-free was the size of your name, and the reputation that you would build. That was the only security you really had. So I have the utmost respect for guys that decided to “run away with the circus”. Because in the ’60s and ’70s, that was probably very much what it was like. In a larger sense, my take on wrestling as a business, or as a wing of entertainment, is one very much on the outside. I have a production company that handles wrestling-related topics, and works with wrestlers. I didn’t have to go through what these guys went  through. So I couldn’t speak to it from a first-person standpoint. But from so much of what I see, it was kind of the “bastard child” of entertainment. We’re talking about when there was no WWE film division producing The Marine. I’m talking about these times where they were living out of a suitcase. For a while there, even though there was mainstream attention in the ’80s, it was always still the punchline to a joke. For the intelligentsia, Andy Warhol was in the crowd at Madison Square Garden. But it was always a comical anecdote. It was always, when covered by a sportscaster, covered with a wink and a smile, and always signed off with a chuckle at the end. It was never given any credence akin to any other legitimate sport, or any other legitimate form of entertainment. And that’s because it’s neither. It’s the most unique thing. They call it “sports entertainment”. But it’s not sports. There are unions in sports. These guys have collective bargaining. All professional U.S. sports are franchise-based. So it’s not sports. It’s not even entertainment either. Because entertainers have a union. They have collective bargaining power, and health benefits. They work for a studio for a time as an employee, and then they’ll be signed to another studio when the next film gets started. So it’s very unique. You really can’t compare it very honestly to either one.

through. So I couldn’t speak to it from a first-person standpoint. But from so much of what I see, it was kind of the “bastard child” of entertainment. We’re talking about when there was no WWE film division producing The Marine. I’m talking about these times where they were living out of a suitcase. For a while there, even though there was mainstream attention in the ’80s, it was always still the punchline to a joke. For the intelligentsia, Andy Warhol was in the crowd at Madison Square Garden. But it was always a comical anecdote. It was always, when covered by a sportscaster, covered with a wink and a smile, and always signed off with a chuckle at the end. It was never given any credence akin to any other legitimate sport, or any other legitimate form of entertainment. And that’s because it’s neither. It’s the most unique thing. They call it “sports entertainment”. But it’s not sports. There are unions in sports. These guys have collective bargaining. All professional U.S. sports are franchise-based. So it’s not sports. It’s not even entertainment either. Because entertainers have a union. They have collective bargaining power, and health benefits. They work for a studio for a time as an employee, and then they’ll be signed to another studio when the next film gets started. So it’s very unique. You really can’t compare it very honestly to either one.

What does Kayfabe Commentaries provide that WWE-produced documentaries don’t?

We each have one advantage over each other. WWE has a very big advantage over us, because they can show footage of everything they’re talking about. They can show matches. They can show angles, interviews, because they own pretty much every library out there. Our advantage over them is that we can be honest. They can’t. They can’t from a liability standpoint, and because they would be dredging up a lot of stuff that they would really like to never see the light of day again. They can’t put unsanitized opinions out, because it’s commentary on their company. So I feel that we do operate in a state of grace. And no matter how much they attempt to emulate shoot programming, they always have to have a leg in the work. Because sometimes the truth is a dark dirty story, and they can’t go there. I understand why they can’t. But that’s their disadvantage. They’ve tried to emulate what they’ve seen in the shoot industry. They’ve emulated a lot of our material very blatantly. If they use that as inspiration, I guess that’s fine, provided there’s no trademark violation. But I know that we will always have that upper-hand. Because they can’t let their guard down, and let the stars say exactly what they want to.

We each have one advantage over each other. WWE has a very big advantage over us, because they can show footage of everything they’re talking about. They can show matches. They can show angles, interviews, because they own pretty much every library out there. Our advantage over them is that we can be honest. They can’t. They can’t from a liability standpoint, and because they would be dredging up a lot of stuff that they would really like to never see the light of day again. They can’t put unsanitized opinions out, because it’s commentary on their company. So I feel that we do operate in a state of grace. And no matter how much they attempt to emulate shoot programming, they always have to have a leg in the work. Because sometimes the truth is a dark dirty story, and they can’t go there. I understand why they can’t. But that’s their disadvantage. They’ve tried to emulate what they’ve seen in the shoot industry. They’ve emulated a lot of our material very blatantly. If they use that as inspiration, I guess that’s fine, provided there’s no trademark violation. But I know that we will always have that upper-hand. Because they can’t let their guard down, and let the stars say exactly what they want to.

Some [of those stars] come through with that “nothing to lose” kind of attitude. But we’ve spoken to people who were under WWE Legends contracts when they worked with us. So we kind of run the gamut when we get people. The only people we can’t work with would be anybody who’s signed to a current WWE performance contract on television — part of their regular RAW or Smackdown roster. But outside of that, everybody’s pretty much fair game.

Who was your favorite wrestler on the microphone, and in the ring?

The greatest worker on the microphone I’ve ever seen is Roddy Piper. Probably because — and I don’t mean to say this insultingly; only to heighten the importance of how brilliant he was holding a microphone — his skills in the ring were so absent. He could have a very proficient short match. But it was his ability to talk people into the building which was his gift. I think Piper is the standard bearer for someone who can pick up a microphone and incite a riot.

The greatest worker on the microphone I’ve ever seen is Roddy Piper. Probably because — and I don’t mean to say this insultingly; only to heighten the importance of how brilliant he was holding a microphone — his skills in the ring were so absent. He could have a very proficient short match. But it was his ability to talk people into the building which was his gift. I think Piper is the standard bearer for someone who can pick up a microphone and incite a riot.

Skilled workers in the ring? Bret Hart was a great worker. Paul Orndorff‘s level believability was great. He never looked like he wasn’t murdering who he was in the ring with. Some of the early high-fliers that were taking those early chances, like Jimmy Snuka were so very impressive. Today, actually, for as much as I’ve disparaged today’s product, I think the sheer athleticism of the men and women in the ring today is probably right up there with the best of years ago. These guys have to rely on it. The pace of these matches are so much faster, and the spectacle that’s demanded by the fans — because the business has changed — requires these guys to be part-acrobat, part-wrestler, really in shape, and extremely impressive from a physical standpoint. So a lot of the guys today probably would stack up with some of the best technicians of old. But the real point of differentiation between yesterday and today are guys that could stand there, look at a camera, look you dead in the eye, and you believed them. I don’t think there’s very many today that I believe.

What effect did the Canadian, Japanese and Mexican markets have in U.S. wrestling?

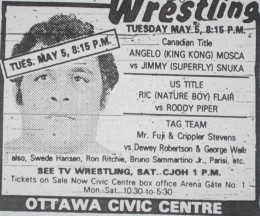

The U.S. and Canadian relationship was always very close. There was always an active talent share. The Tunneys, years ago operating out of Toronto, Stu Hart in Calgary. Those were places that you’d stop when you were a wrestler doing the circuit. Talking back in the territory days here — 1970s-80s. That was a place that you’d be sent to work. So the U.S. and Canada had that talent share.

The U.S. and Canadian relationship was always very close. There was always an active talent share. The Tunneys, years ago operating out of Toronto, Stu Hart in Calgary. Those were places that you’d stop when you were a wrestler doing the circuit. Talking back in the territory days here — 1970s-80s. That was a place that you’d be sent to work. So the U.S. and Canada had that talent share.

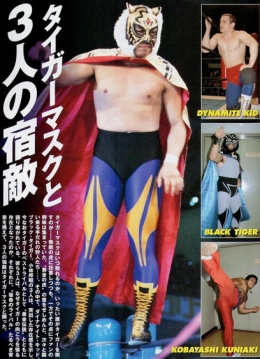

Japan was one of those rare places where you’d head over, and if you were one of the American guys that made a connection with the fans in some bizarre way — and they kind of latched onto you as a heel — you could make a lot of money. Guys like Bruiser Brody, Abdullah the Butcher, Vader later on — these were guys that made a lot of money in Japan, because they connected with those fans as heels, as the foreigners. So if you were a specialty act like that? Yeah, you could go to Japan with some regularity, a couple of months a year, and make a ton of cash. Also,  the Dynamite Kid had a very big Japanese following, because his style at that time was very similar to the young Japanese workers.

the Dynamite Kid had a very big Japanese following, because his style at that time was very similar to the young Japanese workers.

When big Japanese names would come here, like [Antonio] Inoki, it was touted as a noteworthy event. They obviously wouldn’t stay here. Their bread and butter was over there. But they would stay here for extended periods of time. So it was like a specialty act, or kind of a noteworthy occasion.

[Mexican Lucha] had a huge impact in the mid-90s. Up until then, it was nil. You’d get some guy like Mil Máscaras who could come up and had that crossover. They were stars down there legitimately, but then would come here and have decent-sized television runs for U.S. federations. The real appreciation for international talent I think happened when, for the lack of a better term, the “dirt sheets” first came out. People were able to track international results, read about stars overseas, get on the internet and trade tapes, and be able to see those guys. So their big boom, particularly the luchas, coincided with that. Then Kevin Sullivan put them on TV on [Monday] Nitro, and they went from being what was intended to be just kind of a fun fast-paced part of the night, to something that people tuned in for. I mean, they were a draw when you’d start seeing guys like [Rey] Mysterio and Konnan. It was that fast-paced style, smaller guys, high-flying. The stuff you see now in the ring, basically, that’s a lot of what was brought to the table when the luchadores were put on Nitro. They got a huge following from that. So their part in history is very big.

Did not seeing lucha wrestlers faces hurt their marketability in the U.S.?

That’s a tough one. Vince Russo took some heat for a comment he made about not being able to see the face under a hood, and it limiting appeal on television. I think there’s a lot to that. However, there’s a cultural divide here. Because in Mexico, the mask is as much of the tradition as anything. So they don’t expect anything other than that. I mean, that’s the standard fare there. The importance of the mask carries great tradition, and it’s handled very seriously. Here, it never was. So I do think fans here — maybe myself included, even — shortchange the marketability of someone who can’t sell with their face in the ring, but also be on camera and be a salable face for the company. Mysterio has the bottom part chopped out, and they did something interesting with the eyes. So they were able to maximize as much as they could in the face, and allow him to keep a hood, by showing off the mouth, the jawline and the eyes. I guess it did limit the marketability of many of those guys, and kept them as secondary acts in many cases.

That’s a tough one. Vince Russo took some heat for a comment he made about not being able to see the face under a hood, and it limiting appeal on television. I think there’s a lot to that. However, there’s a cultural divide here. Because in Mexico, the mask is as much of the tradition as anything. So they don’t expect anything other than that. I mean, that’s the standard fare there. The importance of the mask carries great tradition, and it’s handled very seriously. Here, it never was. So I do think fans here — maybe myself included, even — shortchange the marketability of someone who can’t sell with their face in the ring, but also be on camera and be a salable face for the company. Mysterio has the bottom part chopped out, and they did something interesting with the eyes. So they were able to maximize as much as they could in the face, and allow him to keep a hood, by showing off the mouth, the jawline and the eyes. I guess it did limit the marketability of many of those guys, and kept them as secondary acts in many cases.

Kane was a one-off, basically. You wouldn’t have five wrestlers in the ring fulfilling the same function as Kane. He could be hidden, because that was part of his character. He was stoic. We didn’t need to see his face. It was more frightening not seeing his face. The whole Jason thing. You can’t see what’s going on behind the mask, so you’re terrified. And that was that character’s goal: strike fear. He was not going to passionately implicitly crawl to the corner looking for the tag, like the Ricky Morton face, when he wants to tag out and get the sympathy of hundreds of preteens. That wasn’t Kane’s goal. His goal was just to strike fear.

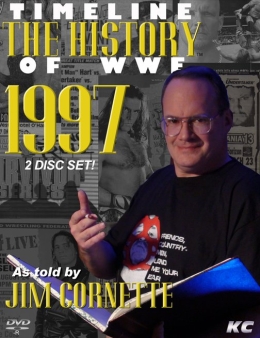

What does Jim Cornette bring to Kayfabe Commentaries?

Jim was somebody that was always shoot interview gold, because of his honesty first of all. But also, he’s just one of those guys that’s entertaining to listen to. He’s got a flair for language, so people enjoy hearing his take on stuff. He’s able to convey ideas in an entertaining way. So that’s the base: entertaining to watch. Many of the guys we get, that haven’t been seen many other places, people are surprised by. I say, “Why?” And they say, “He wasn’t a big name at the time, but I really enjoyed watching him talk about blah blah blah.” Very important for us to balance, and to remember  before we book talent, the size of the name and the ability for them to be entertaining for two hours — not always hand-in-hand. So Corny’s one of those guys that you listen to read the phone book, and there’d be something entertaining about it. He’s able to get his ideas across in a very unique way, to say the least. You know, our stuff is very highly-formatted, and Jim’s one of the very few people in the business that can do a lot of our programming. He was a booker, so he can do Guest Booker, which only features people who have booked in major federations. He was in the office, involved in creative in the WWE, so he can do Timeline and talk about all the events of 1997. He was creatively involved, and a mainstay on television in WCW, so he qualifies to do Timeline: The History of WCW. He’s a very interesting character, so we featured him on Ring Roasts, and did a comedic tribute to him. Corny can do almost all of our shows. Not many people can. [Kevin] Nash is somebody who can also. So that’s why he pops up. Also, the requisite for anyone who’s gonna be a guest on YouShoot is they’ve gotta be a bit of a lightening rod to elicit a lot of fan reaction. That’s a show where the interviews are conducted entirely by the fans through their submitted email questions and videos. So you want someone who’s going to get us a few hundred videos and emails for us to sift through and put together an entertaining show. Cornette fills that bill too. So Cornette is kind of the quintessential guest for us, because he can touch so much of our programming.

before we book talent, the size of the name and the ability for them to be entertaining for two hours — not always hand-in-hand. So Corny’s one of those guys that you listen to read the phone book, and there’d be something entertaining about it. He’s able to get his ideas across in a very unique way, to say the least. You know, our stuff is very highly-formatted, and Jim’s one of the very few people in the business that can do a lot of our programming. He was a booker, so he can do Guest Booker, which only features people who have booked in major federations. He was in the office, involved in creative in the WWE, so he can do Timeline and talk about all the events of 1997. He was creatively involved, and a mainstay on television in WCW, so he qualifies to do Timeline: The History of WCW. He’s a very interesting character, so we featured him on Ring Roasts, and did a comedic tribute to him. Corny can do almost all of our shows. Not many people can. [Kevin] Nash is somebody who can also. So that’s why he pops up. Also, the requisite for anyone who’s gonna be a guest on YouShoot is they’ve gotta be a bit of a lightening rod to elicit a lot of fan reaction. That’s a show where the interviews are conducted entirely by the fans through their submitted email questions and videos. So you want someone who’s going to get us a few hundred videos and emails for us to sift through and put together an entertaining show. Cornette fills that bill too. So Cornette is kind of the quintessential guest for us, because he can touch so much of our programming.

Why is Vince Russo so disliked?

He is the designated bad guy. I think he takes a lot of heat for things that probably weren’t even his responsibility — more of a viewership move. You look at the popular programming among young people in the ’90s, and it was stuff like The Real World on MTV. It was that element of reality, that little bit of danger, and a little bit dirty. Just the way stuff was going. Vince is a student of pop  culture, of film, and TV. So he just looked at what was going on in the other forms of media, and he added it to wrestling. Now, why would the wrestling purist hate that? Because the wrestling purist aligns themselves more with the sensibilities of the product they grew up on. The Harley Races, the Bruno Sammartinos, even the early Hogan stuff. Look, there was plenty of ridiculous stuff that we grew up on in the ’80s that we accepted, because we were kids. We grow up, and now we look back at it fondly. But goddamn it, if it was happening today, we’d want to string up the person that put the Rock ‘n’ Wrestling cartoon on CBS. We would look at that as heresy. But we look back with warm fuzzy memories, because we were kids. But if Vince Russo did it today, we’d wanna lynch him. So that’s what he did, and I think that’s why he gets a lot of the heat.

culture, of film, and TV. So he just looked at what was going on in the other forms of media, and he added it to wrestling. Now, why would the wrestling purist hate that? Because the wrestling purist aligns themselves more with the sensibilities of the product they grew up on. The Harley Races, the Bruno Sammartinos, even the early Hogan stuff. Look, there was plenty of ridiculous stuff that we grew up on in the ’80s that we accepted, because we were kids. We grow up, and now we look back at it fondly. But goddamn it, if it was happening today, we’d want to string up the person that put the Rock ‘n’ Wrestling cartoon on CBS. We would look at that as heresy. But we look back with warm fuzzy memories, because we were kids. But if Vince Russo did it today, we’d wanna lynch him. So that’s what he did, and I think that’s why he gets a lot of the heat.

In his Timeline: The History of WCW. He was able to name names. Whereas in the past, he’d been a little more diplomatic, because I think he is done with wrestling. I think he’s admitted that he is done with wrestling. Even though you’d always hear that he’s done with wrestling, and then he’d have a book come out, and then another book come out, and then he’d do an interview here, an interview there. I think he just wanted a lot of it expunged — get it out of his system, and move on. He’s a business owner now. He owns some franchises out in Colorado, and he’s very much into doing that. He’s writing also, but not for wrestling. He’s writing some more legit entertainment stuff. I guess he wanted to kind of come clean a little bit, and name some names. Hey, it must be hard to have to sit there and read that much crap about yourself for 15 years.

How did pro wrestling in the 1990s mirror the American people it was playing to?

I don’t think it mirrored us as a people, as much as it did our tastes in popular culture. I think it was very closely tied to what we saw, and what we expected to see in all forms of entertainment. In the mid-’90s with gangsta rap, filling our headphones with ultra-violence. No double entendre in their message. It was very clear what was being stated. Movies that [Quentin] Tarantino was putting out, where the bad guys were the good guys. That was all ECW. And then, WWE takes its cue from Paul E, and we get the scratch logo and the “Attitude Era“, and bad guys are the good guys. We don’t have to make decisions to cultivate a heel or a babyface. The more nasty that someone is, the better. That culture of cool-to-be-bad that Tarantino was propagating, that was guys like [“Stone Cold” Steve] Austin, and guys that talked like that. We wanted to be bad like them. So I don’t think as a people we were changed societally. But I think it was just a shadow of popular culture in music and in movies — what we cheer for, what we buy, what we think is cool off those shelves, we also do with wrestling. Just as today, there’s so much of an emphasis on special effects in movies, the amount of CGI that’s in almost any film is remarkable. And so, now you can’t have an opening of a wrestling TV show unless there’s 45 seconds of pyro and it looks like the arena’s exploding.

What does Kevin Nash bring to KC interviews?

Kevin is one of my favorite people to work with in this format, because he’s very precise. First of all, he’s got opinions about everything. He’s one of these guys that’s interesting to listen to. He’s got strong opinions. He’s got a point of view. He’s not afraid to speak his mind. Another one of these guys where they’re bigger than having to worry. A lot of the smaller guys answers are sometimes tempered with “Ooh, I want a call from Connecticut again, so I better be careful how I answer this.” Kevin was too big in his era to really worry about that stuff. So he kind of lays it on the line. He’s definitely a great addition to our programming.

Kevin was a basketball guy. Blew his knee out. Somebody said, “Hey listen, you’re a wrestler.” And that was it. But once he got there, he cared about the product. He didn’t shit on it. He took it seriously. Guys that he hung with were guys that loved the business. Of course, they were all concerned with their spot in the business. But tell me anyone that works anywhere that’s not concerned about their spot in their job, who doesn’t get defensive about their spot in their job, who doesn’t raise an eyebrow when someone walks in to the factory — and guess what, they’re being trained on what you’re being trained on, and they’re a lot younger and cheaper than you. That would happen anywhere. Why do we expect a different set of rules because it’s wrestling? I don’t think that it matters that somebody had a passion, and wanted to be in  the business — the boyhood dream. I don’t think we need the boyhood dream in everybody. As long as when they get here, they do the business service, and that they’re not laughing at us. Now, there are other people — and I think Lex Luger would today tell you that he was one of these guys — that didn’t really care about wrestling, big-picture. A guy that got in because of his body, and maybe didn’t have a love for the business like we hear a lot of the guys did. So maybe that’s more in line with someone fans would point some of that criticism at, at the time when Lex was getting his ride. I think Lex is a different guy, based on the time I spent with him. And I think he looks back at some of those attitudes that he had in his earlier days in the business as being incorrect. I don’t think Kevin’s in that category though. I think Kevin cared very much about doing the right thing for wrestling, in addition to doing the right thing for himself. Shouldn’t everyone make what they can make while they can make it? Especially in a business where you could be done tomorrow. The wrong injury and you’re done. Let’s take this just from strictly an entertainment point of view. There’s a hierarchy in what people are worth. There really is. You will deal with a lot more crap if you can get Tom Cruise in your film. He gives you a lot of crap, and gives everybody else a lot of crap, and you’ve gotta pay him a lot of money. You’ll deal with that, because you have a bit of a guarantee of a box office at the other side of that. He is, simply put, worth more. People in entertainment, and in wrestling, are a product. They’re people, but there’s a product too. And it’s all what the product is worth. So I think there is a sliding scale. Now, when you talk about the wellness of an individual, that’s a different ballgame.

the business — the boyhood dream. I don’t think we need the boyhood dream in everybody. As long as when they get here, they do the business service, and that they’re not laughing at us. Now, there are other people — and I think Lex Luger would today tell you that he was one of these guys — that didn’t really care about wrestling, big-picture. A guy that got in because of his body, and maybe didn’t have a love for the business like we hear a lot of the guys did. So maybe that’s more in line with someone fans would point some of that criticism at, at the time when Lex was getting his ride. I think Lex is a different guy, based on the time I spent with him. And I think he looks back at some of those attitudes that he had in his earlier days in the business as being incorrect. I don’t think Kevin’s in that category though. I think Kevin cared very much about doing the right thing for wrestling, in addition to doing the right thing for himself. Shouldn’t everyone make what they can make while they can make it? Especially in a business where you could be done tomorrow. The wrong injury and you’re done. Let’s take this just from strictly an entertainment point of view. There’s a hierarchy in what people are worth. There really is. You will deal with a lot more crap if you can get Tom Cruise in your film. He gives you a lot of crap, and gives everybody else a lot of crap, and you’ve gotta pay him a lot of money. You’ll deal with that, because you have a bit of a guarantee of a box office at the other side of that. He is, simply put, worth more. People in entertainment, and in wrestling, are a product. They’re people, but there’s a product too. And it’s all what the product is worth. So I think there is a sliding scale. Now, when you talk about the wellness of an individual, that’s a different ballgame.

Regardless of how big of a draw that person was — and we dealt with this in Marty Jannetty’s show — they put their health at risk for you. Not just their health for the time that they’re working with you, but for the ability to live a comfortable life for the rest of their life. They’ve put that on the line for you. So I think there’s a responsibility, no matter the size of the name. That’s not to diminish the fact that Marty Jannetty was a name in tag-team wrestling in the WWE for a while. If he’s good enough to draw you that money on “C shows”, he’s probably worth enough to make sure he gets his ankle fixed. Certainly if you’re putting somebody [else] in rehab 6,7,8 times, you could probably do somebody a service and get their ankle fixed once — if that ankle is a direct result of bouncing around your rings for 15 years. Just my opinion though.

17 years later, what is the legacy of the “Montreal Screwjob”?

It’s been talked to death, but it was uniquely interesting, because it was the intersection of a work in the ring and everything we knew was going on outside the ring. And it all culminated on television, on the WWE product, which made it very unique. You didn’t have the shoot stuff show up on TV that much. Guys would drop something out of their mouth here or there in the ring — “sunny days” and all that stuff. So that was a little nudge to the smart fans that were sitting at home going, “Oh, he’s talking to me.” But when that all exploded on TV, it garnered so much attention because of that. I’ve talked to people on camera about it, and I’ve talked to more people off camera about it. As a matter of fact, a release we have coming up first half of 2014 is an edition of Guest Booker with Bruce Prichard. The edition is called “Screwing Bret” and it’s about the Montreal Screwjob. Prichard was working creative at the time, so he takes us into that entire night. There was only a few people who were in the room after it happened with Vince and Bret, and Bruce was one of them. So this is all firsthand stuff that he gives us, and it’s quite interesting. Anyway, my take from the moment I saw it? I haven’t been able to be swayed convincingly yet, and I’ve talked to people that were there. The bell rings. The match is over. Shawn Michaels has won the heavyweight

It’s been talked to death, but it was uniquely interesting, because it was the intersection of a work in the ring and everything we knew was going on outside the ring. And it all culminated on television, on the WWE product, which made it very unique. You didn’t have the shoot stuff show up on TV that much. Guys would drop something out of their mouth here or there in the ring — “sunny days” and all that stuff. So that was a little nudge to the smart fans that were sitting at home going, “Oh, he’s talking to me.” But when that all exploded on TV, it garnered so much attention because of that. I’ve talked to people on camera about it, and I’ve talked to more people off camera about it. As a matter of fact, a release we have coming up first half of 2014 is an edition of Guest Booker with Bruce Prichard. The edition is called “Screwing Bret” and it’s about the Montreal Screwjob. Prichard was working creative at the time, so he takes us into that entire night. There was only a few people who were in the room after it happened with Vince and Bret, and Bruce was one of them. So this is all firsthand stuff that he gives us, and it’s quite interesting. Anyway, my take from the moment I saw it? I haven’t been able to be swayed convincingly yet, and I’ve talked to people that were there. The bell rings. The match is over. Shawn Michaels has won the heavyweight  championship with a submission in the middle of the ring. The camera cuts to Bret’s face as a close-up. Why? No one knew about this, right? No one in the truck knew about this. This is all a big secret between “The Kliq” and Vince and [Earl] Hebner. Why would the director call a cut to the loser’s face? A guy just won a title. Never seen a cut to the loser. Odd. Why was it so important for me to see the expression on Bret’s face? Why did the WWE need me to see how disappointed and angry Bret was at that moment? Why the display outside the ring of Bret smashing monitors that cost, I don’t know, 100 bucks maybe — when he could have gone backstage, stormed the truck, and destroyed $50,000 worth of monitors and $200,000 worth of TV equipment? Why did we need a public showing of him breaking a couple of monitors at ringside? Safe enough to not cause too much damage. But boy, to let us know that he’s still mad and that he got screwed. Here is the situation at the time:

championship with a submission in the middle of the ring. The camera cuts to Bret’s face as a close-up. Why? No one knew about this, right? No one in the truck knew about this. This is all a big secret between “The Kliq” and Vince and [Earl] Hebner. Why would the director call a cut to the loser’s face? A guy just won a title. Never seen a cut to the loser. Odd. Why was it so important for me to see the expression on Bret’s face? Why did the WWE need me to see how disappointed and angry Bret was at that moment? Why the display outside the ring of Bret smashing monitors that cost, I don’t know, 100 bucks maybe — when he could have gone backstage, stormed the truck, and destroyed $50,000 worth of monitors and $200,000 worth of TV equipment? Why did we need a public showing of him breaking a couple of monitors at ringside? Safe enough to not cause too much damage. But boy, to let us know that he’s still mad and that he got screwed. Here is the situation at the time:  Bret wants to leave. Bret can’t be payed any more by Vince. That was all true. That was all happening. Contract was too big. With the financial peril that Vince was going through, he needed to get out of that contract. Bret has a title. Doesn’t want to lose face in Canada. Wants to be able to get on WCW, make the big bucks. Vince needs his title back. How can you do all of that, and still get Vince the title back that night before the following Monday night’s broadcast of Nitro? Have Bret save face having to lose in Canada. Have Vince now spin off and to become one of the biggest heels with one of the most successful runs against one of their most successful babyfaces, Steve Austin in years. How can everyone come out getting what they want? Well, you saw how everyone can come out. Everyone being happy, while documentary cameras are rolling, by the way. How coincidental is all this stuff? Vince gets his title back. Bret didn’t lose in Canada. Bret got “screwed” in Canada, where he was still a babyface. And that crowd that night led the charge against the evil McMahon, when they saw their hometown hero get screwed by him. Spun the business in a different direction. Vince took out his most popular hero. Bret was able to leave the belt, no fault of his own, and head over to WCW and make the big contract money. Everybody came out smelling like a rose. Possible if it was screwjob? I wonder.

Bret wants to leave. Bret can’t be payed any more by Vince. That was all true. That was all happening. Contract was too big. With the financial peril that Vince was going through, he needed to get out of that contract. Bret has a title. Doesn’t want to lose face in Canada. Wants to be able to get on WCW, make the big bucks. Vince needs his title back. How can you do all of that, and still get Vince the title back that night before the following Monday night’s broadcast of Nitro? Have Bret save face having to lose in Canada. Have Vince now spin off and to become one of the biggest heels with one of the most successful runs against one of their most successful babyfaces, Steve Austin in years. How can everyone come out getting what they want? Well, you saw how everyone can come out. Everyone being happy, while documentary cameras are rolling, by the way. How coincidental is all this stuff? Vince gets his title back. Bret didn’t lose in Canada. Bret got “screwed” in Canada, where he was still a babyface. And that crowd that night led the charge against the evil McMahon, when they saw their hometown hero get screwed by him. Spun the business in a different direction. Vince took out his most popular hero. Bret was able to leave the belt, no fault of his own, and head over to WCW and make the big contract money. Everybody came out smelling like a rose. Possible if it was screwjob? I wonder.

How much of a threat did the WCW pose to Vince McMahon by outspending him in the 1990s?

Vince did the right thing. He scaled back where he had to scale back. I think he was smart enough to know that this too shall pass. I mean, here’s a guy that had been through federal indictments, the bizarre sex scandal in the early ’90s with the “ring boys” and all that stuff. He learned a real strategy of how to hunker down — to build a bunker, wait out the storm, and then go out guns blazing when it’s time to go out guns blazing again. That was clearly his strategy. He didn’t overpay. When Kevin Nash went to him and said, “I just got a 3-year offer from the other guys,” Vince said, “Can’t do it Kev. Good luck.” Whereas the other side would have opened their checkbook and wrote a check they couldn’t cash, as they continued to lose money. So what it ultimately came down to in the midst of this war… I mean, both sides were landing heavy body blows on each other. But it was who was able to conserve enough energy, that when the fight got into the later rounds, was able to keep themselves together. And I think WCW expended everything it had in the early rounds, and there was nothing left. Also, it’s significant to know that Turner was bought by Time Warner, and they probably had absolutely no intention of having a pro wrestling company on its slate of products. Time magazine was also on it, and America Online, which at the time was a huge internet service provider, and it spun off into news and a million different directions. I’m not so sure they wanted wrestling on the slate, and it wasn’t making very much money at the time anyway. It was losing money. So it was good business sense for them to get rid of it.

Vince did the right thing. He scaled back where he had to scale back. I think he was smart enough to know that this too shall pass. I mean, here’s a guy that had been through federal indictments, the bizarre sex scandal in the early ’90s with the “ring boys” and all that stuff. He learned a real strategy of how to hunker down — to build a bunker, wait out the storm, and then go out guns blazing when it’s time to go out guns blazing again. That was clearly his strategy. He didn’t overpay. When Kevin Nash went to him and said, “I just got a 3-year offer from the other guys,” Vince said, “Can’t do it Kev. Good luck.” Whereas the other side would have opened their checkbook and wrote a check they couldn’t cash, as they continued to lose money. So what it ultimately came down to in the midst of this war… I mean, both sides were landing heavy body blows on each other. But it was who was able to conserve enough energy, that when the fight got into the later rounds, was able to keep themselves together. And I think WCW expended everything it had in the early rounds, and there was nothing left. Also, it’s significant to know that Turner was bought by Time Warner, and they probably had absolutely no intention of having a pro wrestling company on its slate of products. Time magazine was also on it, and America Online, which at the time was a huge internet service provider, and it spun off into news and a million different directions. I’m not so sure they wanted wrestling on the slate, and it wasn’t making very much money at the time anyway. It was losing money. So it was good business sense for them to get rid of it.

Do you think fans care if wrestlers use steroids?

No, I don’t think anyone cares. And that’s what I didn’t understand at the time, when people were talking about “the steroid trial”, “the sex trial”, all this stuff. I don’t think the fans cared at all. About the biggest thing that would have happened was you would have had your product money get held up, because McMahon would have been behind bars and couldn’t have been running the day-to-day operations of the company. I think a lot of what happened with the steroids stuff was unfair. Steroids were legal for a long time. Guys made their living by being big in wrestling. Then all of a sudden, one day you tell everybody, “By the way, the way you’ve been doing this the whole time, you can’t do  it anymore.” That’s like going to a classroom and telling a teacher, “Keep doing what you’re doing, but you can’t speak English today.” What? So there was no step-down program. There was no curtailing of the process. It was all of a sudden — Couldn’t do it. Illegal. Everyone’s going to jail. How the hell did you expect that to happen? Especially when the business was largely built off of the fact that you had real-life superheroes. Larger than life in stature, and in charisma. That would be a tough order. So I think a lot of what went down was really unfortunate.

it anymore.” That’s like going to a classroom and telling a teacher, “Keep doing what you’re doing, but you can’t speak English today.” What? So there was no step-down program. There was no curtailing of the process. It was all of a sudden — Couldn’t do it. Illegal. Everyone’s going to jail. How the hell did you expect that to happen? Especially when the business was largely built off of the fact that you had real-life superheroes. Larger than life in stature, and in charisma. That would be a tough order. So I think a lot of what went down was really unfortunate.

It’s come up in YouShoot a fair number of times. Fans have asked. We’re cutting Vader’s Timeline: The History of WCW 1993, and he talks about what he did, as far as performance. ’93 was when the testing was happening. So he talked about why he was never affected by the testing, and the substances that he was putting in his body at the time. Guys talk about it pretty freely. Lex Luger’s edition of Timeline: The History of WWE, he talks about it a great deal.

I don’t hear too much about steroids today anymore. You hear about human growth hormone, and there’s always gonna be a performance enhancing drug du jour. As long as we’re talking about athletics, and your paycheck is dependent on you performing at such a high level, I think there’s always gonna be some kind of supplement that someone’s taking. I mean, maybe it’s less than legal, but I think we’re gonna be dealing with this in baseball, football, wrestling forever. Or else, they’d all look like me.

How important was Lanny Poffo’s interview for giving incite into his late brother Randy Savage?

That was a gift is what that was — hearing about Randy’s inner feelings about stuff, his childhood, the family dynamic, and answering some of the mysterious questions about the strife between McMahon and Poffo. The revelation about that Battle Royal in 1988 that Angelo [Poffo] was not allowed to attend. It scarred Randy, because he gave his word to his dad. That stuff was a gift from Lanny. And what did I think of Macho Man? Total package. The physique was one that was not so over-the-top that he wouldn’t be able to survive in an era of performance enhancing drugs, or without performance enhancing drugs. He was unique on the microphone. How many people can say that they’re unique on the microphone. That level of intensity, that whole thing, Lanny said that that was him. I mean, he was that intense and that voice was legit. Certainly it’s a product of a guy who grew up in the business, whose dad was in the business. You know, the neighbor doesn’t talk like that. But that was authentically Randy. So, captivating on the mic, tremendous in the ring, a star everywhere he went. Randy was what wrestling was. So sad that we never got to know more about Randy. He was so reclusive toward the end, and he didn’t sit down with anybody for this type of stuff. He’s one of the very few guys that we needed to hear from. Because we could have learned so much from him. A terrible, terrible loss.

That was a gift is what that was — hearing about Randy’s inner feelings about stuff, his childhood, the family dynamic, and answering some of the mysterious questions about the strife between McMahon and Poffo. The revelation about that Battle Royal in 1988 that Angelo [Poffo] was not allowed to attend. It scarred Randy, because he gave his word to his dad. That stuff was a gift from Lanny. And what did I think of Macho Man? Total package. The physique was one that was not so over-the-top that he wouldn’t be able to survive in an era of performance enhancing drugs, or without performance enhancing drugs. He was unique on the microphone. How many people can say that they’re unique on the microphone. That level of intensity, that whole thing, Lanny said that that was him. I mean, he was that intense and that voice was legit. Certainly it’s a product of a guy who grew up in the business, whose dad was in the business. You know, the neighbor doesn’t talk like that. But that was authentically Randy. So, captivating on the mic, tremendous in the ring, a star everywhere he went. Randy was what wrestling was. So sad that we never got to know more about Randy. He was so reclusive toward the end, and he didn’t sit down with anybody for this type of stuff. He’s one of the very few guys that we needed to hear from. Because we could have learned so much from him. A terrible, terrible loss.