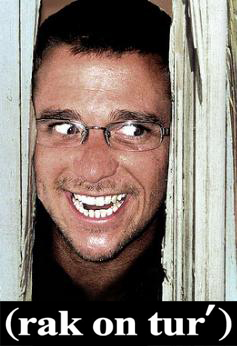

Who: Billy Corben is a Miami-based documentary filmmaker and area native who co-founded and operates film company, Rakontur with his longtime friends/producers Alfred Spellman and David Cypkin. Their 2006 film, Cocaine Cowboys documents Miami’s central role as the major American destination for cocaine smuggled from Colombia during the ’70’s and ’80’s. The effects of this trade on Miami included a major spike in violent crime, and a series of drug-related murders ordered by female cocaine trafficker, Griselda Blanco — the subject of 2008 followup film, Cocaine Cowboys II: Hustlin’ with the Godmother. This was followed by the highest-rated episode of ESPN’s 30 for 30 documentary series, titled The U, following the exploits of the University of Miami football squad during the 1980’s, and the larger racial and cultural shift taking place in both the city and the wider country during that time.

Who: Billy Corben is a Miami-based documentary filmmaker and area native who co-founded and operates film company, Rakontur with his longtime friends/producers Alfred Spellman and David Cypkin. Their 2006 film, Cocaine Cowboys documents Miami’s central role as the major American destination for cocaine smuggled from Colombia during the ’70’s and ’80’s. The effects of this trade on Miami included a major spike in violent crime, and a series of drug-related murders ordered by female cocaine trafficker, Griselda Blanco — the subject of 2008 followup film, Cocaine Cowboys II: Hustlin’ with the Godmother. This was followed by the highest-rated episode of ESPN’s 30 for 30 documentary series, titled The U, following the exploits of the University of Miami football squad during the 1980’s, and the larger racial and cultural shift taking place in both the city and the wider country during that time.  Rakontur’s newest film, Square Grouper delves into South Florida’s ’70’s and ’80’s marijuana smuggling industry, focusing on a branch of the Jamaica-based Ethiopian Zion Coptic Church dwelling in a mansion on Miami’s Star Island; the job-hungry fishermen residents of tiny Everglades City 80 miles west of Miami; and Robert Platshorn – the longest serving marijuana prisoner in U.S. history, who led a group of smugglers known as “The Black Tuna Gang.” The film will premiere on March 12th at the 2011 SxSW Film Festival.

Rakontur’s newest film, Square Grouper delves into South Florida’s ’70’s and ’80’s marijuana smuggling industry, focusing on a branch of the Jamaica-based Ethiopian Zion Coptic Church dwelling in a mansion on Miami’s Star Island; the job-hungry fishermen residents of tiny Everglades City 80 miles west of Miami; and Robert Platshorn – the longest serving marijuana prisoner in U.S. history, who led a group of smugglers known as “The Black Tuna Gang.” The film will premiere on March 12th at the 2011 SxSW Film Festival.

What’s your take on the current crop of luxurious TV portrayals of modern Miami?

Listen, we’re a tourism town, and as long as they want to continue to blast those TV shows that look like tourism brochures or chamber of commerce videos, it’s great. The reality is obviously different for many people here in Miami. It’s not quite as luxurious. It’s not all South Beach and models ‘n bottles. It’s a very different reality in terms of crime, in terms of the housing crisis, the mortgage fraud, and people losing their homes and being underwater in their mortgages, and the empty condominiums that line the downtown Miami skyline. You know, I think the reality is a little bit different. Also, CSI Miami, because they shoot in LA, they have Mexicans playing Cubans. That’s offensive to a lot of the Cubans in Miami,

Listen, we’re a tourism town, and as long as they want to continue to blast those TV shows that look like tourism brochures or chamber of commerce videos, it’s great. The reality is obviously different for many people here in Miami. It’s not quite as luxurious. It’s not all South Beach and models ‘n bottles. It’s a very different reality in terms of crime, in terms of the housing crisis, the mortgage fraud, and people losing their homes and being underwater in their mortgages, and the empty condominiums that line the downtown Miami skyline. You know, I think the reality is a little bit different. Also, CSI Miami, because they shoot in LA, they have Mexicans playing Cubans. That’s offensive to a lot of the Cubans in Miami,  because they look different, their Spanish is different, the slang in different, the gangs are different. So, that’s pretty inaccurate for the most part. Burn Notice is kind of fun, because I think they do both sides a little bit better — you know, crime lab technicians don’t drive around in hummers. But Burn Notice does both sides. I know they do it tongue-in-cheek, but I think they actually depict Miami and the more diverse neighborhoods in Miami, and actually shoot on location in Miami better than most shows do.

because they look different, their Spanish is different, the slang in different, the gangs are different. So, that’s pretty inaccurate for the most part. Burn Notice is kind of fun, because I think they do both sides a little bit better — you know, crime lab technicians don’t drive around in hummers. But Burn Notice does both sides. I know they do it tongue-in-cheek, but I think they actually depict Miami and the more diverse neighborhoods in Miami, and actually shoot on location in Miami better than most shows do.

How did Miami-set films, TV shows and video games affect the financing for Cocaine Cowboys?

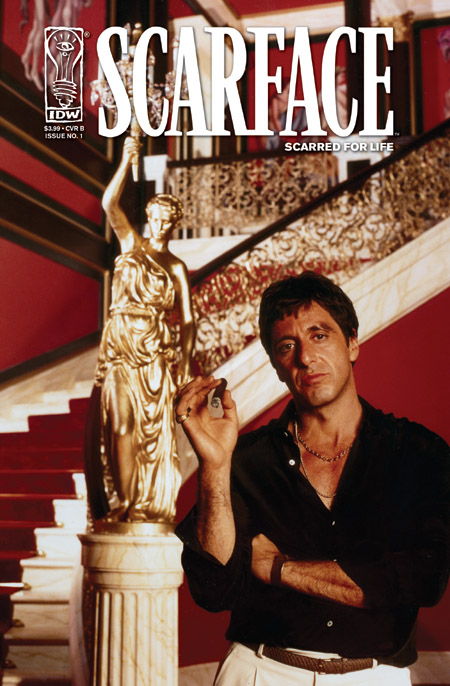

After we had done Sundance [Film Festival] with our first documentary, Raw Deal: A Question of Consent, we attempted industry financing. We failed. The responses we were getting — true to form in the absolute vacuum that people in this industry attempt to function — it was like, “Yeah, haven’t we seen this in Blow already? Haven’t we seen this in Scarface and Miami Vice?” And everybody misunderstood what it was. We were going to non-fiction buyers and financiers and said it was a doc, and it was very difficult to convince people. I don’t think it was a lack of effectiveness in our presentation, so much as just a complete lack of understanding of the significance of doing a real Scarface or real Miami Vice, and how relevant that was culturally even in 2003, or at the time we were trying to make this happen. And part of our pitch at the time was, first of all, Scarface had been recently re-released on DVD for the 20th anniversary. I believe the sales statistics were — from NBC Universal, in terms of their sales records — had outsold Jurassic Park and ET combined on DVD at that time. Miami Vice: Season One was finally being released on DVD. Michael Mann had announced he was finally going to begin pre-production on the long-anticipated Miami Vice feature film, and the best-selling video game of all time at that time was Grand Theft Auto: Vice City. And so,

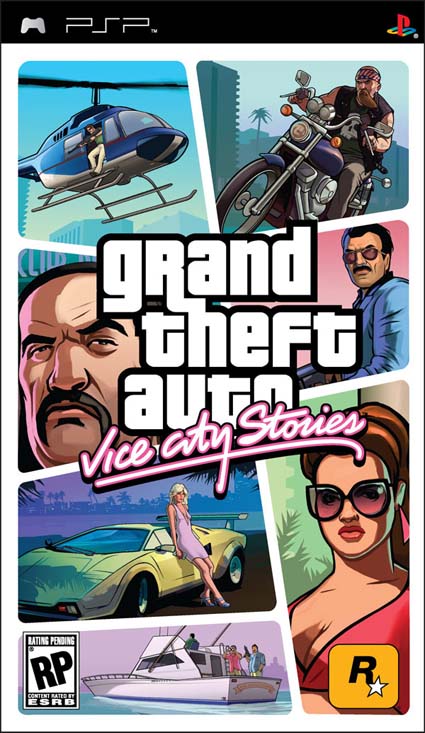

After we had done Sundance [Film Festival] with our first documentary, Raw Deal: A Question of Consent, we attempted industry financing. We failed. The responses we were getting — true to form in the absolute vacuum that people in this industry attempt to function — it was like, “Yeah, haven’t we seen this in Blow already? Haven’t we seen this in Scarface and Miami Vice?” And everybody misunderstood what it was. We were going to non-fiction buyers and financiers and said it was a doc, and it was very difficult to convince people. I don’t think it was a lack of effectiveness in our presentation, so much as just a complete lack of understanding of the significance of doing a real Scarface or real Miami Vice, and how relevant that was culturally even in 2003, or at the time we were trying to make this happen. And part of our pitch at the time was, first of all, Scarface had been recently re-released on DVD for the 20th anniversary. I believe the sales statistics were — from NBC Universal, in terms of their sales records — had outsold Jurassic Park and ET combined on DVD at that time. Miami Vice: Season One was finally being released on DVD. Michael Mann had announced he was finally going to begin pre-production on the long-anticipated Miami Vice feature film, and the best-selling video game of all time at that time was Grand Theft Auto: Vice City. And so, to us it seemed like with the cycle of nostalgia, which seems to come in these 20-year spurts, seemed to be in a legitimate Miami 1980’s nostalgia moment there. Not to mention that you need only watch an episode of MTV’s Cribs at that time to understand the lasting influence and cultural impact of Scarface on an entirely different generation of young people — many of whom weren’t even alive at the time the movie was originally released. So, we thought both creatively and economically that this was just a no-brainer. Everybody agreed later after we released it, suddenly it’s “we’re gonna make a movie, and we’re gonna make a TV series, and we should do a video game!” You know, in 2012 we’ll release our fourth Cocaine Cowboys movie. So, we had to just go out and do it on our own independently. And really, without fail, Vice City was an instigator of this. It really prompted us to say, well, now seems to be our moment to go out and secure financing and distribution and get a story like this told. And the PSP, the handheld Playstation unit, had been released. And Sony had introduced this UMD technology, which were just minidiscs with movies on it that you could watch on your PSP, since downloading movies directly to a handheld device or streaming them had not caught on yet. So, they had this

to us it seemed like with the cycle of nostalgia, which seems to come in these 20-year spurts, seemed to be in a legitimate Miami 1980’s nostalgia moment there. Not to mention that you need only watch an episode of MTV’s Cribs at that time to understand the lasting influence and cultural impact of Scarface on an entirely different generation of young people — many of whom weren’t even alive at the time the movie was originally released. So, we thought both creatively and economically that this was just a no-brainer. Everybody agreed later after we released it, suddenly it’s “we’re gonna make a movie, and we’re gonna make a TV series, and we should do a video game!” You know, in 2012 we’ll release our fourth Cocaine Cowboys movie. So, we had to just go out and do it on our own independently. And really, without fail, Vice City was an instigator of this. It really prompted us to say, well, now seems to be our moment to go out and secure financing and distribution and get a story like this told. And the PSP, the handheld Playstation unit, had been released. And Sony had introduced this UMD technology, which were just minidiscs with movies on it that you could watch on your PSP, since downloading movies directly to a handheld device or streaming them had not caught on yet. So, they had this  technology, and we for a time were in talks with Rockstar Games about debuting Cocaine Cowboys, or at least distributing it, on UMD together with what had been a rumored, but not-yet-announced, PSP sequel to Vice City, which was Vice City Stories. So, we actually talked about pairing up the Vice City Stories PSP game with the UMD of Cocaine Cowboys in the same package. That didn’t happen, but that was an opportunity that we very enthusiastically engaged in discussions with them about before that technology essentially became irrelevant. Before our negotiations could conclude, that technology was obsolete and basically being phased out almost as quickly as it was introduced. And nobody was releasing movies, and distributors weren’t committing to the technology anymore. But it was very exciting for us, seeing as how Rockstar really helped to pave the way in terms of testing the waters for interest. I mean, that world was entirely archetypal 1980’s Miami. The sights, the sounds, the characters, everything was inspired by that.

technology, and we for a time were in talks with Rockstar Games about debuting Cocaine Cowboys, or at least distributing it, on UMD together with what had been a rumored, but not-yet-announced, PSP sequel to Vice City, which was Vice City Stories. So, we actually talked about pairing up the Vice City Stories PSP game with the UMD of Cocaine Cowboys in the same package. That didn’t happen, but that was an opportunity that we very enthusiastically engaged in discussions with them about before that technology essentially became irrelevant. Before our negotiations could conclude, that technology was obsolete and basically being phased out almost as quickly as it was introduced. And nobody was releasing movies, and distributors weren’t committing to the technology anymore. But it was very exciting for us, seeing as how Rockstar really helped to pave the way in terms of testing the waters for interest. I mean, that world was entirely archetypal 1980’s Miami. The sights, the sounds, the characters, everything was inspired by that.

How did the local drug trade affect your Miami neighborhood while growing up the 1980’s?

I remember everybody being very successful. I grew up in a middle-class neighborhood, and everybody had some kind of toy or symbol of their prosperity at the time, whether it was single-family homes with a Porsche in the driveway, or people were adding some sort of addition to the house. These were not people who were in the drug trade, but these were symbols of the trickle-down effect of that revenue. Because everybody in Miami was doing pretty well cash-wise — if you were a car dealer, or a jeweler, or a grocer, or a real estate developer or a home builder — we had an economy that was fueled very heavily by an influx of both legitimate and narco dollars. I never witnessed the drug violence or anything like that, but definitely recall the effect of the drug money. Of course, at the time, I didn’t know that that’s what it was. I just knew that people were doing well. It was a time of prosperity for people in our community — visibly, noticeably. Then, I have very distinct

I remember everybody being very successful. I grew up in a middle-class neighborhood, and everybody had some kind of toy or symbol of their prosperity at the time, whether it was single-family homes with a Porsche in the driveway, or people were adding some sort of addition to the house. These were not people who were in the drug trade, but these were symbols of the trickle-down effect of that revenue. Because everybody in Miami was doing pretty well cash-wise — if you were a car dealer, or a jeweler, or a grocer, or a real estate developer or a home builder — we had an economy that was fueled very heavily by an influx of both legitimate and narco dollars. I never witnessed the drug violence or anything like that, but definitely recall the effect of the drug money. Of course, at the time, I didn’t know that that’s what it was. I just knew that people were doing well. It was a time of prosperity for people in our community — visibly, noticeably. Then, I have very distinct  memories of sitting at the kitchen table while my mother would be making dinner on a weeknight, and the local news would come on at like 5 pm. And I remember seeing the stories, the packages and the images that would eventually wind up in so many of those montages in Cocaine Cowboys. And that was what was on the TV — murder and mayhem. Even our neighborhood was touched by crime. Not specifically drug crime per say, but there was a dramatic rise in crime in general and lawlessness in general. And my dad got a gun, so I remember the gun coming into the house.

memories of sitting at the kitchen table while my mother would be making dinner on a weeknight, and the local news would come on at like 5 pm. And I remember seeing the stories, the packages and the images that would eventually wind up in so many of those montages in Cocaine Cowboys. And that was what was on the TV — murder and mayhem. Even our neighborhood was touched by crime. Not specifically drug crime per say, but there was a dramatic rise in crime in general and lawlessness in general. And my dad got a gun, so I remember the gun coming into the house.

We had the alarm that we set every night when we left the house. There was smash and grabs in the neighborhood — literally would tie a rope to the front doors of homes, and then to the backs of their cars, and drive forward tearing the doors off the hinges. And then they would raid the houses while people were home, while they weren’t home. They’d tie you up, they’d pistol whip you. This was happening to my neighbors at the time. And this was kind of an offshoot of the lawlessness that was introduced into the community by way of the Cocaine Cowboys, and the money, and the corruption, and the influx of weapons and criminals. And  then, of course, Miami Vice would do it all over again. And Scarface. I didn’t see Scarface for the first time, I think, until later in the ’80’s. In ’89 or ’90, I was at my friend [Producer] Dave [Cypkin]’s, who I’ve known since nursery school and we grew up together. It was at his house, because his Dad had taped Scarface off of like Showtime. To tell you the truth, I felt at the time it was pretty accurate from what we’d grown up with — like, “yeah, it’s our childhood.” We’d grown up actually watching De Palma movies, so I knew it was very indicative of his style, in terms of very over the top and operatic from a cinematic standpoint. But I didn’t feel that the content was over the top, as a lot of people thought it was this sort of macabre kind of almost Dario Argento-esque gore which was just kind of absurd — and it was not.

then, of course, Miami Vice would do it all over again. And Scarface. I didn’t see Scarface for the first time, I think, until later in the ’80’s. In ’89 or ’90, I was at my friend [Producer] Dave [Cypkin]’s, who I’ve known since nursery school and we grew up together. It was at his house, because his Dad had taped Scarface off of like Showtime. To tell you the truth, I felt at the time it was pretty accurate from what we’d grown up with — like, “yeah, it’s our childhood.” We’d grown up actually watching De Palma movies, so I knew it was very indicative of his style, in terms of very over the top and operatic from a cinematic standpoint. But I didn’t feel that the content was over the top, as a lot of people thought it was this sort of macabre kind of almost Dario Argento-esque gore which was just kind of absurd — and it was not.

Scarface begins with the Mariel boatlift — what effect did these Cuban refugees have on Miami?

Roughly 125,000 refugees came during the Mariel boatlift, and the percentages or numbers that were hardcore die hard dangerous criminals — that fluctuates from as little as 2,500 or 5,000, all the way up to like 25,000. No one really knows for sure. We do know that entire prisons and mental institutions and hospitals with infirm and elderly and mentally disabled patients were emptied within months of the start of the boatlift. Now, in Cuba at the time, not every prisoner was a violent criminal. Some of them were dissidents who were against Castro’s government. In fact, homosexuals at the time in Cuba were considered mentally insane, so they were in mental institutions. To tell you the truth, the start of Miami’s rather healthy, culturally exciting gay community was born out of the Mariel boatlift.

Roughly 125,000 refugees came during the Mariel boatlift, and the percentages or numbers that were hardcore die hard dangerous criminals — that fluctuates from as little as 2,500 or 5,000, all the way up to like 25,000. No one really knows for sure. We do know that entire prisons and mental institutions and hospitals with infirm and elderly and mentally disabled patients were emptied within months of the start of the boatlift. Now, in Cuba at the time, not every prisoner was a violent criminal. Some of them were dissidents who were against Castro’s government. In fact, homosexuals at the time in Cuba were considered mentally insane, so they were in mental institutions. To tell you the truth, the start of Miami’s rather healthy, culturally exciting gay community was born out of the Mariel boatlift.  That, along with a lot of engineers, and artists and young people who came to America and worked very hard and made incredible contributions to the community. But put yourself in Miami in 1980. By the summer, early fall you are a community who’s absorbing 125,000 new arrivals in a matter of months — many of whom are indigent, some of whom are infirm. These people require food, housing, education, job training, jobs, English language courses, medical care. In of itself, it nearly bankrupted four counties: Monroe, Dade, Broward and Palm Beach. Our public resources were stretched to the max, and the federal government did little or nothing to help us, other than to say, you have to accept these people. “Open arms, open hearts” was the president’s policy,

That, along with a lot of engineers, and artists and young people who came to America and worked very hard and made incredible contributions to the community. But put yourself in Miami in 1980. By the summer, early fall you are a community who’s absorbing 125,000 new arrivals in a matter of months — many of whom are indigent, some of whom are infirm. These people require food, housing, education, job training, jobs, English language courses, medical care. In of itself, it nearly bankrupted four counties: Monroe, Dade, Broward and Palm Beach. Our public resources were stretched to the max, and the federal government did little or nothing to help us, other than to say, you have to accept these people. “Open arms, open hearts” was the president’s policy,  which less than a week later Jimmy Carter backed off of.

which less than a week later Jimmy Carter backed off of.

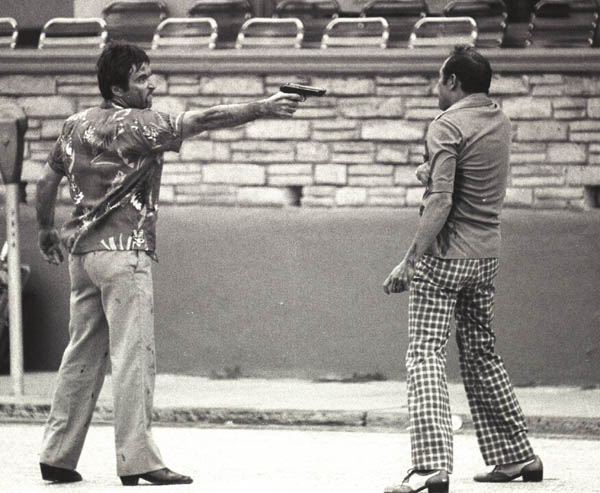

You have to remember what the pulse of the people was, what the sentiment in the community was. There were people who thought that Jimmy Carter should be impeached, because he was in dereliction of duty that bordered on treason — according to some Miamians at the time — as a result of his failure to accomplish one of the fundamental elements of his job, which is to defend our border. People saw this as an invasion, and for many it was, because those are just what we had to absorb by way of the quantity of people. About this percentage, which is apparently unknown to this day, of the dangerous criminals that came in. A lot of them migrated to the city of Miami Beach, which is the barrier island between the Atlantic Ocean and Miami, because it was kind of most like Havana, most like Cuba. It was a seaside, mellow resort town. And I will tell you right now, in less than a year, what happened to reported rapes and violent crimes went through the roof — through the roof — in places like Miami Beach, Hialeah, South Miami, the cities and municipalities in Miami-Dade county where the majority of the criminal Marielitos migrated to within the community. I mean, we’re talking about literal rapes, violent robberies, beatings on the street in broad daylight  — essentially what you saw in the Sun Ray Motel scene in Scarface on Ocean Drive. That was Ocean Drive. They shot it on Ocean Drive. That’s what Ocean Drive looked like. It was these elderly white — many of them, Jewish Holocaust survivors who had survived Hitler, but were ultimately defeated by the Mariel criminals on Miami Beach. And that was a really stunning and shocking scene, that Ocean Drive scene — the “chainsaw scene” as it’s known in Scarface. It really is highly symbolic of Miami at that moment in time, which was this sort of peaceful, somewhat decaying, certainly art deco retirement community/”God’s waiting room.” Then, in came not just the Marielitos, but the Colombian Cocaine Cowboys and this level of lawlessness that tore the community apart and destroyed a lot of lives. And that scene is really emblematic of that.

— essentially what you saw in the Sun Ray Motel scene in Scarface on Ocean Drive. That was Ocean Drive. They shot it on Ocean Drive. That’s what Ocean Drive looked like. It was these elderly white — many of them, Jewish Holocaust survivors who had survived Hitler, but were ultimately defeated by the Mariel criminals on Miami Beach. And that was a really stunning and shocking scene, that Ocean Drive scene — the “chainsaw scene” as it’s known in Scarface. It really is highly symbolic of Miami at that moment in time, which was this sort of peaceful, somewhat decaying, certainly art deco retirement community/”God’s waiting room.” Then, in came not just the Marielitos, but the Colombian Cocaine Cowboys and this level of lawlessness that tore the community apart and destroyed a lot of lives. And that scene is really emblematic of that.

How do Jorge “Rivi” Ayala and other Miami cocaine gangsters compare to cinematic versions?

There was a critic or a blogger who at some point started a review of the movie, couldn’t stop writing about Rivi, and one of his big things was, “I’ve been writing for years that we’ve never seen an honest portrayal of a hitman in cinema by any actor. And this proves it for me.” Saying like, now we have a real hitman, the archetype of a handsome smack-talking gun for hire, and he trumps any of the fictional characters in this mold that we’ve seen before. And it’s true. He’s terribly charming and disarming, and the way I tell it is that he also speaks in a very soft voice. So, when you’re interviewing him in prison, you have to lean in close to him so you can get his mouth closer to your ear. And it’s about that moment that you realize, oh, I could be dead right now very easily, and you understand why he was good at what he did. You have to remind yourself in that moment, holy shit, this is a guy who killed women and children and men with impunity if the price is right, or if there was a price that his boss put on their heads, and wouldn’t think twice about it.

There was a critic or a blogger who at some point started a review of the movie, couldn’t stop writing about Rivi, and one of his big things was, “I’ve been writing for years that we’ve never seen an honest portrayal of a hitman in cinema by any actor. And this proves it for me.” Saying like, now we have a real hitman, the archetype of a handsome smack-talking gun for hire, and he trumps any of the fictional characters in this mold that we’ve seen before. And it’s true. He’s terribly charming and disarming, and the way I tell it is that he also speaks in a very soft voice. So, when you’re interviewing him in prison, you have to lean in close to him so you can get his mouth closer to your ear. And it’s about that moment that you realize, oh, I could be dead right now very easily, and you understand why he was good at what he did. You have to remind yourself in that moment, holy shit, this is a guy who killed women and children and men with impunity if the price is right, or if there was a price that his boss put on their heads, and wouldn’t think twice about it.  So, he was very chilling and effective in that way — the way he put you at ease actually in his presence. I mean, we realized the movie was kind of a three-act structure in terms of the subject matter: drugs, money and murder. That was the story. It was the drugs, the money that came from it and then the necessity of having to enforce a trade that generated that kind of money, because it’s a consignment business. You give someone two kilos, three kilos. You come back next week, you say, “where’s my 150 grand or 200 grand?” And if they don’t have it, it’s not like you take them to court. You know, you have to enforce your trade off the books, if you will, and they did that with enforcers and hitmen like Rivi. And so, we knew we had to get somebody from that role. Rivi is in a very unique situation, because he had a plea bargain with the state attorney in Miami-Dade county where he could speak chapter and verse on all of his murders and crimes that he committed in

So, he was very chilling and effective in that way — the way he put you at ease actually in his presence. I mean, we realized the movie was kind of a three-act structure in terms of the subject matter: drugs, money and murder. That was the story. It was the drugs, the money that came from it and then the necessity of having to enforce a trade that generated that kind of money, because it’s a consignment business. You give someone two kilos, three kilos. You come back next week, you say, “where’s my 150 grand or 200 grand?” And if they don’t have it, it’s not like you take them to court. You know, you have to enforce your trade off the books, if you will, and they did that with enforcers and hitmen like Rivi. And so, we knew we had to get somebody from that role. Rivi is in a very unique situation, because he had a plea bargain with the state attorney in Miami-Dade county where he could speak chapter and verse on all of his murders and crimes that he committed in  Miami-Dade county without fear of the death penalty. He essentially pled to three life sentences in exchange for his cooperation, and to avoid the electric chair at the time. We don’t use the electric chair any more — “Old Sparky” as it’s called down here. In fact, [Producer] Alfred [Spellman] corresponded with other hitmen who worked for Griselda Blanco — “La Madrina” — including Miguel Perez, who was the Marielito who committed the attempted murder on Papo Mejia at Miami International Airport with the World War II bayonet, where he stabbed him like six times and the guy survived. Miguel Perez, we met him in prison, and went so far as to set up the equipment for an interview he agreed to. And then, he was escorted by the prison guard to

Miami-Dade county without fear of the death penalty. He essentially pled to three life sentences in exchange for his cooperation, and to avoid the electric chair at the time. We don’t use the electric chair any more — “Old Sparky” as it’s called down here. In fact, [Producer] Alfred [Spellman] corresponded with other hitmen who worked for Griselda Blanco — “La Madrina” — including Miguel Perez, who was the Marielito who committed the attempted murder on Papo Mejia at Miami International Airport with the World War II bayonet, where he stabbed him like six times and the guy survived. Miguel Perez, we met him in prison, and went so far as to set up the equipment for an interview he agreed to. And then, he was escorted by the prison guard to  the set, and he said, “I can’t do it. My lawyer says I shouldn’t do it.”

the set, and he said, “I can’t do it. My lawyer says I shouldn’t do it.”

And then there was Cumbamba, who you might recall earlier in the move, he helps with the [Herman] Grenados murder. This was the murder that Rivi had fucked up at the Jacaranda nightclub. That was the first time he met Griselda, who said, “Well, you’ve got to help us find him.” Rivi didn’t do this hit. But he helped them locate Grenados by paging a guy who knew him, or whatever. And he came, and that’s the guy whose blood they drained in the bathtub, and then broke his bones, so they could fold him up and put him in that box alongside the highway that we had the crime scene photos for. So Cumbamba, the guy who was involved in that hit, Alfred wrote him in prison. He was in prison in Louisiana for the murder of Barry Seal, the CIA operative turned drug informant who was murdered by Colombian hitmen in Baton Rouge at a  halfway house. He’s actually going to be in the Cocaine Cowboys remix this summer — a whole segment about him. But Alfred wrote to Cumbamba, who wrote him back and said he didn’t have the same deal that Rivi had, so he didn’t want to speak on crimes in Florida. He was doing his time in Louisiana, and wanted to finish that out in peace. He might have life there, but didn’t want to be extradited to face the death penalty. So, Alfred said, “well, Cumbamba says he won’t do the interview, but he wants to know if we’d like a surreal watercolor painting that he did in prison.” And I believe my answer to Alfred was, “fuck yes.” And he never sent it, unfortunately.

halfway house. He’s actually going to be in the Cocaine Cowboys remix this summer — a whole segment about him. But Alfred wrote to Cumbamba, who wrote him back and said he didn’t have the same deal that Rivi had, so he didn’t want to speak on crimes in Florida. He was doing his time in Louisiana, and wanted to finish that out in peace. He might have life there, but didn’t want to be extradited to face the death penalty. So, Alfred said, “well, Cumbamba says he won’t do the interview, but he wants to know if we’d like a surreal watercolor painting that he did in prison.” And I believe my answer to Alfred was, “fuck yes.” And he never sent it, unfortunately.

Were the Star Island-based Ethiopian Zion Coptics earnest in their beliefs, or was it all a front?

Lindsey Snell, our producer on Square Grouper, and I were recording the commentary for the DVD. One of the things we talked about was the enduring conflict or controversy of the Zion Coptics. Were they true believers, or was this just a front for what was, without question, a massive marijuana smuggling operation? We know that they were a massive marijuana smuggling operation. We know that, because they were caught red-handed no less than three times with massive quantities of marijuana. I mean, I’m talking about like 14 tons, 19 tons, these are real quantities that they were busted with in November of ’77 and February of ’78. So, there was no doubt that they were marijuana smugglers. The question is absolutely the enduring debatable issue of that. You know, Square Grouper’s a triptych — three separate pot haulin’ stories — part one being the Zion Coptics. And from the Coptics that we’ve spoken to: Brother Butch, Brother Gary, Sister Eileen, Brother Clifton and his wife, Carl Olsen — who we didn’t interview for the movie and who has quit

Lindsey Snell, our producer on Square Grouper, and I were recording the commentary for the DVD. One of the things we talked about was the enduring conflict or controversy of the Zion Coptics. Were they true believers, or was this just a front for what was, without question, a massive marijuana smuggling operation? We know that they were a massive marijuana smuggling operation. We know that, because they were caught red-handed no less than three times with massive quantities of marijuana. I mean, I’m talking about like 14 tons, 19 tons, these are real quantities that they were busted with in November of ’77 and February of ’78. So, there was no doubt that they were marijuana smugglers. The question is absolutely the enduring debatable issue of that. You know, Square Grouper’s a triptych — three separate pot haulin’ stories — part one being the Zion Coptics. And from the Coptics that we’ve spoken to: Brother Butch, Brother Gary, Sister Eileen, Brother Clifton and his wife, Carl Olsen — who we didn’t interview for the movie and who has quit  smoking ganja, but who is a major high-profile activist in the medicinal marijuana campaign — the men and women we’ve met, yes, true believers. They certainly believe that they were young and naive, perhaps idealistic at the time, and regret some of the tactics and decisions that they made. But they believe that ganja is an herb, is a plant that grows from the earth. They believe that God intended us to have it, and that our forefathers, the framers of the Constitution and the founders of America, had intended us to build an economy around it — not the economy, but an economy. They preach the gospel as sincerely now as they did then, now with the benefit of some wisdom and experience and time. Were there opportunists and people who worked with them, or joined the organization, that were in it for the money? Positively. I don’t think there’s any doubt about that either. I can’t name all of them, because I don’t know every single person that was involved. We just interviewed one of them, Tony Darwin. He was a pilot who happened to do some time with Brother Clifton [Middleton], who was second-in-command in Miami.

smoking ganja, but who is a major high-profile activist in the medicinal marijuana campaign — the men and women we’ve met, yes, true believers. They certainly believe that they were young and naive, perhaps idealistic at the time, and regret some of the tactics and decisions that they made. But they believe that ganja is an herb, is a plant that grows from the earth. They believe that God intended us to have it, and that our forefathers, the framers of the Constitution and the founders of America, had intended us to build an economy around it — not the economy, but an economy. They preach the gospel as sincerely now as they did then, now with the benefit of some wisdom and experience and time. Were there opportunists and people who worked with them, or joined the organization, that were in it for the money? Positively. I don’t think there’s any doubt about that either. I can’t name all of them, because I don’t know every single person that was involved. We just interviewed one of them, Tony Darwin. He was a pilot who happened to do some time with Brother Clifton [Middleton], who was second-in-command in Miami.  Under his alias, Peter Sheets, he personally bought Star Island house for $275,000 in cash. And so, after Brother Louv, he was second-in-command in America, and third-in-command in the whole organization [behind] Keith Gordon — the cult of personality was built around him. He was the Jamaican guy who helped found the church and run the church in Jamaica. All of the Coptics, all of them — and you had 19 of them indicted by the federal government, looking at as many as 15 years in prison, which I think is ultimately what Brother Louv was sentenced to — and Tony Darwin, who was not a Coptic Brother, but was a pilot who saw an opportunity to make some money and to fly his plane and go on adventures in the marijuana trade, and had no qualms about doing so — he also did 10 or 15 years. My point is though, nobody flipped. Nobody cooperated. This was unprecedented — probably continues to be unprecedented — that in an indictment of that size in an organization of that size facing the sentences, and you’re looking down the barrel of the federal government’s arsenal, that not a single Brother or Sister, and even this guy Tony Darwin — and, poor guy, he was tried with them. He was tried in the same courtroom as these guys who showed up to

Under his alias, Peter Sheets, he personally bought Star Island house for $275,000 in cash. And so, after Brother Louv, he was second-in-command in America, and third-in-command in the whole organization [behind] Keith Gordon — the cult of personality was built around him. He was the Jamaican guy who helped found the church and run the church in Jamaica. All of the Coptics, all of them — and you had 19 of them indicted by the federal government, looking at as many as 15 years in prison, which I think is ultimately what Brother Louv was sentenced to — and Tony Darwin, who was not a Coptic Brother, but was a pilot who saw an opportunity to make some money and to fly his plane and go on adventures in the marijuana trade, and had no qualms about doing so — he also did 10 or 15 years. My point is though, nobody flipped. Nobody cooperated. This was unprecedented — probably continues to be unprecedented — that in an indictment of that size in an organization of that size facing the sentences, and you’re looking down the barrel of the federal government’s arsenal, that not a single Brother or Sister, and even this guy Tony Darwin — and, poor guy, he was tried with them. He was tried in the same courtroom as these guys who showed up to  court in their ceremonial Jamaican-flag-colored garbs and gowns, with their long beards and their uncut toenails and their sandals. They made it a show trial to try to get their message across to the American people — ahead of their time, perhaps. And [Darwin]’s here clean shaven and white suit and tie going like “man, I’m gonna go to prison for a long time if these guys keep up this circus here.” He could of testified against them. He might have avoided jail time altogether. Nobody flipped, because he liked them, and he believed in them and their sincerity and their cause. And very easily any one of them could have gotten out of significant, or possibly any, prison time. I don’t think there’s a single case we’ve ever looked at where someone didn’t cooperate in an effort to save their own hide. Certainly the other cases in Square Grouper: Everglades City and “Black Tuna,” wanted to cooperate.

court in their ceremonial Jamaican-flag-colored garbs and gowns, with their long beards and their uncut toenails and their sandals. They made it a show trial to try to get their message across to the American people — ahead of their time, perhaps. And [Darwin]’s here clean shaven and white suit and tie going like “man, I’m gonna go to prison for a long time if these guys keep up this circus here.” He could of testified against them. He might have avoided jail time altogether. Nobody flipped, because he liked them, and he believed in them and their sincerity and their cause. And very easily any one of them could have gotten out of significant, or possibly any, prison time. I don’t think there’s a single case we’ve ever looked at where someone didn’t cooperate in an effort to save their own hide. Certainly the other cases in Square Grouper: Everglades City and “Black Tuna,” wanted to cooperate.

What is the story of Everglades City, and to what extent did the residents turn on one another?

In that case it was sort of tragic, because there was a lot of family members flipping on other family members. But at that point, the government pretty much knew everything and, really, it was a matter of pleading guilty or everybody pointing the finger at each other in a great big circle in order to try to get the minimum sentence. Some people cooperated, some people didn’t. Some people turned in family members. Other people just said, “OK, you tell on me, I’ll tell on you,” just to give the appearance of cooperation. But some people legitimately did cooperate in an effort to reduce their sentence, and at least temporarily — and probably in the long term — ruined a lot of people’s lives and families.

In that case it was sort of tragic, because there was a lot of family members flipping on other family members. But at that point, the government pretty much knew everything and, really, it was a matter of pleading guilty or everybody pointing the finger at each other in a great big circle in order to try to get the minimum sentence. Some people cooperated, some people didn’t. Some people turned in family members. Other people just said, “OK, you tell on me, I’ll tell on you,” just to give the appearance of cooperation. But some people legitimately did cooperate in an effort to reduce their sentence, and at least temporarily — and probably in the long term — ruined a lot of people’s lives and families.

[Everglades City]’s a little more than halfway to Naples from Miami-Dade County. Naples is on the West Coast of Florida. So, you literally drive through the everglades, the swamp, and a little more than halfway there’s a crossroads with a blinking red light. It’s basically a stop sign. They need a blinking red light, because there’s no lights out there. It’s the middle of the swamp, so if they had a stop sign, everybody would just fly right through it and you wouldn’t see it. You stop there, and there’s a sign that says “Everglades City” a couple miles that way to the left. There happens to be a gas station there and a sheriff’s office now at that intersection. You turn and drive over a bridge, and there’s two islands: Everglades City, and then another bridge that takes you to Chuckaluskee. And that’s it. Population, steady around 500 for the last several decades, and five family names in the entire town. And it is a fishing village literally in the middle of nowhere. They call it “the last frontier,” and anything that they could do on the water or bring in on the water, that’s what they would do. And that means

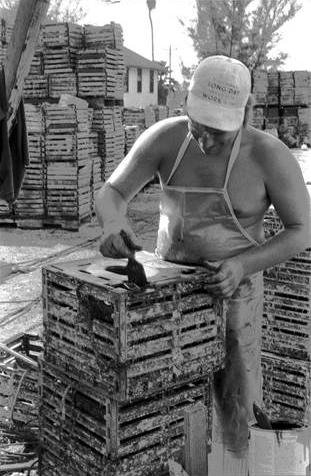

[Everglades City]’s a little more than halfway to Naples from Miami-Dade County. Naples is on the West Coast of Florida. So, you literally drive through the everglades, the swamp, and a little more than halfway there’s a crossroads with a blinking red light. It’s basically a stop sign. They need a blinking red light, because there’s no lights out there. It’s the middle of the swamp, so if they had a stop sign, everybody would just fly right through it and you wouldn’t see it. You stop there, and there’s a sign that says “Everglades City” a couple miles that way to the left. There happens to be a gas station there and a sheriff’s office now at that intersection. You turn and drive over a bridge, and there’s two islands: Everglades City, and then another bridge that takes you to Chuckaluskee. And that’s it. Population, steady around 500 for the last several decades, and five family names in the entire town. And it is a fishing village literally in the middle of nowhere. They call it “the last frontier,” and anything that they could do on the water or bring in on the water, that’s what they would do. And that means  poaching, ostrich plumes, Chinese immigrants, gator hides and eventually they kind of made their way to fishing, stone crabbing. They had a line on the river where they have all the fish houses. And what happened was [U.S. President Harry] Truman came in and dedicated Everglades National Park, and the waters became protected, and progressively more and more restrictions were placed on fishing in that area. This is the way the natives tell it. I’ll put it to you that way, and it’s historically accurate, but it also to a certain extent is a justification for why this happened. Commercial fishing was being squeezed out of the national park, and that was essentially the legitimate lifehood of the vast majority, if not the totality, of Everglades City and Chuckaluskee — with the minimal amount of tourism coming in, and airboat rides, and fishing trips, and charters and that sort of thing. But mostly it was the commercial fishing. And the licenses that did exist, that were “grandfathered” in, but with an expiration date — that was the fine print — they were expiring progressively. The Mark Hunter story about it when he was working down in the Miami market in that time, he said that the federal government essentially told the citizens of Everglades City to find some other way to make a living. And they did. They had their boats. They had their marine charts and maps. And they made good use of them, and started to head on down to Colombia and Jamaica and meet mother ships off the coast, and started pot haulin’.

poaching, ostrich plumes, Chinese immigrants, gator hides and eventually they kind of made their way to fishing, stone crabbing. They had a line on the river where they have all the fish houses. And what happened was [U.S. President Harry] Truman came in and dedicated Everglades National Park, and the waters became protected, and progressively more and more restrictions were placed on fishing in that area. This is the way the natives tell it. I’ll put it to you that way, and it’s historically accurate, but it also to a certain extent is a justification for why this happened. Commercial fishing was being squeezed out of the national park, and that was essentially the legitimate lifehood of the vast majority, if not the totality, of Everglades City and Chuckaluskee — with the minimal amount of tourism coming in, and airboat rides, and fishing trips, and charters and that sort of thing. But mostly it was the commercial fishing. And the licenses that did exist, that were “grandfathered” in, but with an expiration date — that was the fine print — they were expiring progressively. The Mark Hunter story about it when he was working down in the Miami market in that time, he said that the federal government essentially told the citizens of Everglades City to find some other way to make a living. And they did. They had their boats. They had their marine charts and maps. And they made good use of them, and started to head on down to Colombia and Jamaica and meet mother ships off the coast, and started pot haulin’.  And these are God-fearing church-going people. Many of them would whoop their kids behinds if they caught ’em smoking pot. In fact, one of the fellas tells us he was selling nickle and dime bags, and stuff like that — he was a pot dealer — and his dad caught him, and was like, “this is ridiculous. You’re not a drug dealer. If you want to make money, you come on the boat and you’ll help us haul some weight, and then you can make money in transportation. You’re not some street hustler.” You know, he disapproved of that. But then it turned into like the Beverly Hillbillies, because the next thing you know, all these folks have got money. There was one funny story about a wife who got so excited that she called into the city and had trucks come and deliver all new furniture for her house — new beds, new couches, new chairs, new dining room set, the works — and it got there, and there was no room in the house for all the furniture she had ordered. Her house was so small. They literally, after they had moved all the old furniture out, could not put all the furniture in. So, what did they do? They built additions to their houses. They bought the red wagons, which were very popular at the time. They had gold chains. It sort of transformed this little town. We’re talking less than 500 people, and what eventually happened was 80% of the male population was arrested for marijuana smuggling. There was two or three major raids — Operation Everglades, Operation

And these are God-fearing church-going people. Many of them would whoop their kids behinds if they caught ’em smoking pot. In fact, one of the fellas tells us he was selling nickle and dime bags, and stuff like that — he was a pot dealer — and his dad caught him, and was like, “this is ridiculous. You’re not a drug dealer. If you want to make money, you come on the boat and you’ll help us haul some weight, and then you can make money in transportation. You’re not some street hustler.” You know, he disapproved of that. But then it turned into like the Beverly Hillbillies, because the next thing you know, all these folks have got money. There was one funny story about a wife who got so excited that she called into the city and had trucks come and deliver all new furniture for her house — new beds, new couches, new chairs, new dining room set, the works — and it got there, and there was no room in the house for all the furniture she had ordered. Her house was so small. They literally, after they had moved all the old furniture out, could not put all the furniture in. So, what did they do? They built additions to their houses. They bought the red wagons, which were very popular at the time. They had gold chains. It sort of transformed this little town. We’re talking less than 500 people, and what eventually happened was 80% of the male population was arrested for marijuana smuggling. There was two or three major raids — Operation Everglades, Operation  Everglades II was like ’83-’84, and then ’89 I think was called Operation Peacekeeper. It was really over that span of time and, mind you, there were minor busts that occurred before that and in between those events. Those were the three major busts, but the first one, Operation Everglades, was the most famous. I mean, that’s the one where they cut off the one road in and out of town and surrounded the waters with a marine patrol, and they tipped off the press in Miami and Naples, and they all came before sunrise and blocked off the town. And before that, they had one marine patrol officer that patrolled all the waters, and they knew where he lived. So, they knew when he was working. They knew when he wasn’t working.

Everglades II was like ’83-’84, and then ’89 I think was called Operation Peacekeeper. It was really over that span of time and, mind you, there were minor busts that occurred before that and in between those events. Those were the three major busts, but the first one, Operation Everglades, was the most famous. I mean, that’s the one where they cut off the one road in and out of town and surrounded the waters with a marine patrol, and they tipped off the press in Miami and Naples, and they all came before sunrise and blocked off the town. And before that, they had one marine patrol officer that patrolled all the waters, and they knew where he lived. So, they knew when he was working. They knew when he wasn’t working.  Sometimes they would put a tip out that there was this load coming in tonight. So, he’d go out all night. He’d sit there in the mosquitoes getting eaten to death. These mosquitoes are insane out there. We had to get like 100% deet, whatever the hell that means, in order just to go out and shoot. So, he’d sit there all night getting eaten alive. Nothing would happen. He’d finally go home in the morning, and while he was home asleep the next night is when the load actually came in. So, that’s what’s happening before this incredible show of force.

Sometimes they would put a tip out that there was this load coming in tonight. So, he’d go out all night. He’d sit there in the mosquitoes getting eaten to death. These mosquitoes are insane out there. We had to get like 100% deet, whatever the hell that means, in order just to go out and shoot. So, he’d sit there all night getting eaten alive. Nothing would happen. He’d finally go home in the morning, and while he was home asleep the next night is when the load actually came in. So, that’s what’s happening before this incredible show of force.

Is corruption still as big a problem in Miami as it was during the police scandals of the 1980’s?

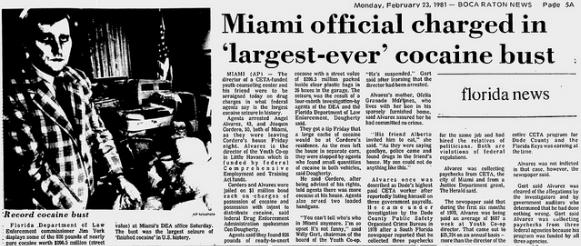

It’s not just our police force. It’s our public officials. It’s politicians. It’s governmental agencies, bureaucrats, code compliance officers, parking enforcement, the tow truck mafia — to this day is South Florida’s single greatest challenge. The Forbes list of America’s [20] Most Miserable Cities — the good news is we’re not number one. The bad news is we’re number two, up from number six whenever the last time Forbes did this. The only town more miserable than us, according to Forbes criteria, is Stockton, California. So, otherwise, we’re most-miserable in the country. And Miami to this

It’s not just our police force. It’s our public officials. It’s politicians. It’s governmental agencies, bureaucrats, code compliance officers, parking enforcement, the tow truck mafia — to this day is South Florida’s single greatest challenge. The Forbes list of America’s [20] Most Miserable Cities — the good news is we’re not number one. The bad news is we’re number two, up from number six whenever the last time Forbes did this. The only town more miserable than us, according to Forbes criteria, is Stockton, California. So, otherwise, we’re most-miserable in the country. And Miami to this  day, and the state of Florida, continues to rank on the top of all the bad lists and the bottom of all the good lists. Whether it’s education, we’re on the bottom. Whether it’s misery, or traffic, or quality of life, or foreclosures or public corruption — we are at the top of all of those lists. I mean, top five or ten cities in the country, sometimes the world. And it’s not inaccurate. I don’t think we’re being unfairly depicted by these lists, no matter how limited the criteria might be, or how open the criteria that the chamber of commerce types bemoan. I think public corruption is one of our greatest challenges as a community to this day, in terms of being a legitimate part of society in this country, and not just dismissed as a banana republic — which we really have been and have tried to shed that image, to not great success unfortunately. And it’s not just the police. I mean, compared to thirty years ago, the police have certainly cleaned up their act. The police force, you’re always gonna have bad apples. But 30 years ago, yes, there existed criminal enterprises operating from inside

day, and the state of Florida, continues to rank on the top of all the bad lists and the bottom of all the good lists. Whether it’s education, we’re on the bottom. Whether it’s misery, or traffic, or quality of life, or foreclosures or public corruption — we are at the top of all of those lists. I mean, top five or ten cities in the country, sometimes the world. And it’s not inaccurate. I don’t think we’re being unfairly depicted by these lists, no matter how limited the criteria might be, or how open the criteria that the chamber of commerce types bemoan. I think public corruption is one of our greatest challenges as a community to this day, in terms of being a legitimate part of society in this country, and not just dismissed as a banana republic — which we really have been and have tried to shed that image, to not great success unfortunately. And it’s not just the police. I mean, compared to thirty years ago, the police have certainly cleaned up their act. The police force, you’re always gonna have bad apples. But 30 years ago, yes, there existed criminal enterprises operating from inside  police departments. Whether it was the “Cocaine Cops” in ’79, which was a whole squad of homicide detectives in Metro Dade County. And then the Miami River Cops scandal in the early mid-’80’s that literally just destroyed the city of Miami police department as we knew it at that time. What was interesting though, is that these were not good cops gone bad back then. These were bad guys that became cops. As you’ll recall in the movie, Edna Buchanan, the Pulitzer Prize-winning crime journalist from The Miami Herald talks about the standard of entry for officers in the city of Miami. What happened was, in the late ’70’s there was a consent decree in litigation between the City of Miami PBA and and the federal government, and that consent degree said that the police department had to adjust its hiring practices so that the demographics of the police force better represented the demographic of the community. That officially meant, not in legalese, but to translate — more minority, particularly Latin, officers on the police force.

police departments. Whether it was the “Cocaine Cops” in ’79, which was a whole squad of homicide detectives in Metro Dade County. And then the Miami River Cops scandal in the early mid-’80’s that literally just destroyed the city of Miami police department as we knew it at that time. What was interesting though, is that these were not good cops gone bad back then. These were bad guys that became cops. As you’ll recall in the movie, Edna Buchanan, the Pulitzer Prize-winning crime journalist from The Miami Herald talks about the standard of entry for officers in the city of Miami. What happened was, in the late ’70’s there was a consent decree in litigation between the City of Miami PBA and and the federal government, and that consent degree said that the police department had to adjust its hiring practices so that the demographics of the police force better represented the demographic of the community. That officially meant, not in legalese, but to translate — more minority, particularly Latin, officers on the police force.  So, as Edna Buchanan describes it in the movie, they found they could not hire more of these officers unless they reduced the rather high standards and qualifications they had at the time. And they did that to the point where criminals said “hey, imagine if we could run a criminal organization, but have a badge.” It wasn’t like cops went bad, or the power went to their head or anything. These were criminals who became cops and then began running, essentially, a cocaine enterprise out of the police department. We don’t have that anymore. It’s not institutional corruption in the police department. But really, broadly speaking across the public spectrum, that’s one of the things that Forbes looked at. We had like 404 politicians or public officers charged with a crime over the last decade or more. That’s insane. And I know getting indicted in of itself is not proof of guilt, but it’s still pretty outrageous. And I just think that when people talk about why are we always the worst of everything down here, I think that’s our single greatest challenge.

So, as Edna Buchanan describes it in the movie, they found they could not hire more of these officers unless they reduced the rather high standards and qualifications they had at the time. And they did that to the point where criminals said “hey, imagine if we could run a criminal organization, but have a badge.” It wasn’t like cops went bad, or the power went to their head or anything. These were criminals who became cops and then began running, essentially, a cocaine enterprise out of the police department. We don’t have that anymore. It’s not institutional corruption in the police department. But really, broadly speaking across the public spectrum, that’s one of the things that Forbes looked at. We had like 404 politicians or public officers charged with a crime over the last decade or more. That’s insane. And I know getting indicted in of itself is not proof of guilt, but it’s still pretty outrageous. And I just think that when people talk about why are we always the worst of everything down here, I think that’s our single greatest challenge.

0 Comments