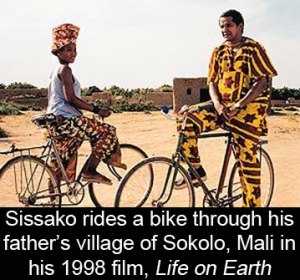

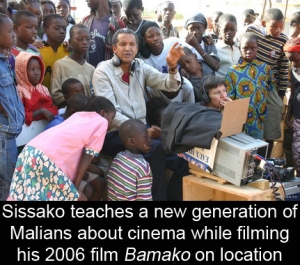

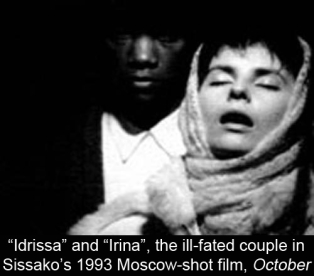

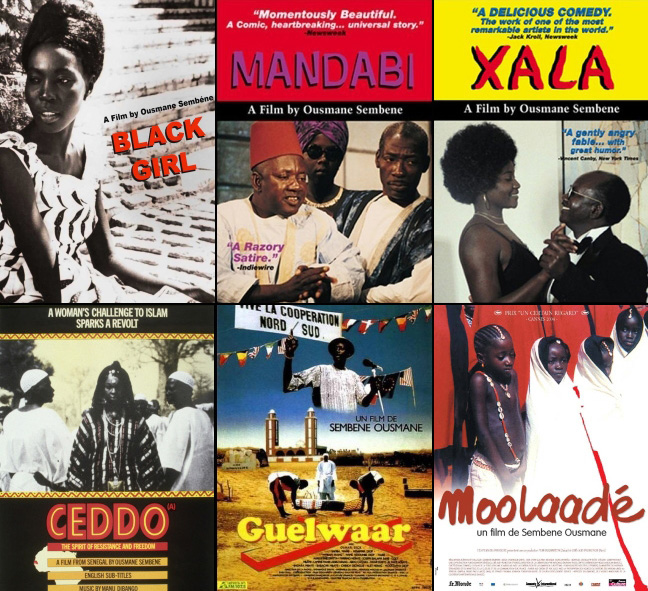

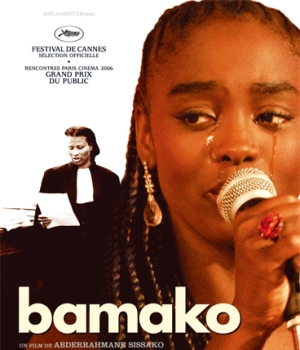

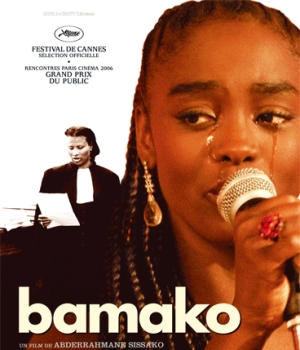

Who: Abderrahmane Sissako is a Mauritanian-born, Mali-raised filmmaker whose cinematic training was done at Moscow’s Federal State Film Institute during the 1980s. The program concluded with his first film, the 23-minute short Le Jeu [The Game], which he shot in Turkmenistan to double for Mauritania. His next film was the 37-minute short October, shot around Moscow and following the romantic relationship of an interracial couple. Sissako followed these with a series of films shot around Africa. These included the 1997 documentary Rostov-Luanda, about his journey to Angola to search for an old friend from film school, and 2006’s Bamako, which centers on a trial in the capital city of Mali. The trial serves to judge the impact of the World Bank and International Monetary Fund on the country’s people, and Sissako cast real judges and lawyers for the film’s court scenes. For the role of “Le procureur”, Sissako tried to recruit influential Senegalese filmmaker Ousmane Sembène, but was turned down, and the following year Sembène passed away. But in April of 2013, Sissako visited New York City to attend the 20th New York African Film Festival at Film Society of Lincoln Center, where two of his films (Life on Earth and October) were shown — as were two of Sembène’s (Borom Sarret and Guelwaar),whom the festival honored as the “father of African Cinema.” Camera In The Sun sat down with Sissako during his visit to New York, and discussed the production of his early films, Le Jeu and October, his thoughts on Sembène and the conflict in Northern Mali.

Who: Abderrahmane Sissako is a Mauritanian-born, Mali-raised filmmaker whose cinematic training was done at Moscow’s Federal State Film Institute during the 1980s. The program concluded with his first film, the 23-minute short Le Jeu [The Game], which he shot in Turkmenistan to double for Mauritania. His next film was the 37-minute short October, shot around Moscow and following the romantic relationship of an interracial couple. Sissako followed these with a series of films shot around Africa. These included the 1997 documentary Rostov-Luanda, about his journey to Angola to search for an old friend from film school, and 2006’s Bamako, which centers on a trial in the capital city of Mali. The trial serves to judge the impact of the World Bank and International Monetary Fund on the country’s people, and Sissako cast real judges and lawyers for the film’s court scenes. For the role of “Le procureur”, Sissako tried to recruit influential Senegalese filmmaker Ousmane Sembène, but was turned down, and the following year Sembène passed away. But in April of 2013, Sissako visited New York City to attend the 20th New York African Film Festival at Film Society of Lincoln Center, where two of his films (Life on Earth and October) were shown — as were two of Sembène’s (Borom Sarret and Guelwaar),whom the festival honored as the “father of African Cinema.” Camera In The Sun sat down with Sissako during his visit to New York, and discussed the production of his early films, Le Jeu and October, his thoughts on Sembène and the conflict in Northern Mali.

Do you think language is a barrier to your films being more widely appreciated?

For me, cinema is interesting and special, because it’s the language of image. And when I think about a movie, I really think about image. It means for me every subject of drama is universal. For example, before I got back from Russia, where I lived for more than 10 years, of course I thought in Russian for the construction of ideas. But then I lived in Paris, of course I thought in French. But it was just how to communicate. The language of cinema or any drama is universal for me.

Why did you decide to go to Russia to study film?

First, not only in this time but also now, the big problem for young Africans was we didn’t have the opportunity to choose something — not where to travel, or where to study. If we got an opportunity, any opportunity, to do something different or to go somewhere… because to go somewhere, for me, is the most important thing for a human being. When the situation for any person is he doesn’t have the choice to do something, that is difficult and terrible. Just to resume, when I was 19, I got the opportunity to go to Moscow to learn cinema, and only the Soviet Union gave me this opportunity. And sometimes people think, “It was because you are a Communist.” No. Any young guy is a Communist in some way. And that is not a problem, to have the concept of sharing what we have. That is important for me, this vision. But I got this opportunity to go to Moscow to learn, and it was a big chance for me.

I think for me, cinema, or to make movies, or any act of creation is the research of yourself. If you ask me to make a movie about anything, of course I will do something like an autobiography. It doesn’t mean your autobiography is special or not. No. For me, it’s really important to start with what you know, what you have experienced, and to go somewhere. October is like this. Of course I  used my own experience with ambition to tell something universal. That is ambition. And also, that is a most difficult thing.

used my own experience with ambition to tell something universal. That is ambition. And also, that is a most difficult thing.

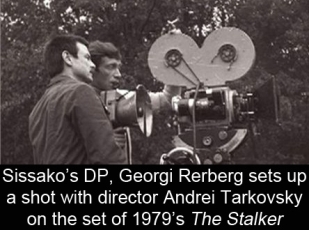

[In film school,] the most important thing for me, and the most difficult, was if you want to be a filmmaker, the dangerous thing is to have big enthusiasm. Enthusiasm is not always a good thing. And in this school, they killed the pretend. It’s really interesting when you stop pretending that art is easy. “I just need a camera to make my movie.” No. In this school they tried to explain to me, “Go slowly.” That was interesting for me. But also interesting was when I came to this school — and like today — I wasn’t very interested in seeing movies. I’m not a cinefile. I’m not this guy. When I came to Moscow, to the school, I saw maybe three or four movies in my life. And It’s a different thing to like movies, and to make films. That’s a completely different thing. And for this reason, when I discovered the world cinema — when I saw in school Cassavetes, John Ford, or Antonioni, or Bergman, or Tarkovsky — that was for me, a young guy who wanted to be a filmmaker, watching their movies on a great big screen in a big theater, that was important.

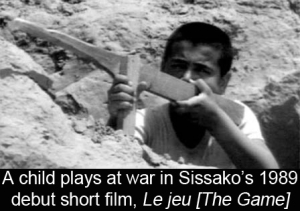

Do you think Turkmenistan doubled well for Mauritania in Le Jeu?

Yes, because it was desert, and deserts are similar. Maybe with some changes. But if you shoot a movie in the desert, you don’t need to show desert. As a filmmaker, you need to cut that, not to show desert. Because it’s not interesting in the cinema. And it’s also the most difficult thing, to shoot a movie in the desert. And I knew that before, and for me it was normal. The most important thing was for me to tell a story in the place where the most important thing will be my character. That is one. The second thing, the place, was also important for me, because I didn’t get the opportunity to shoot my movie in Mauritania. And Turkmenistan was, for me, the only opportunity to do that. And also, the people from there look like Mauritanians, because they are desert people. And it was interesting, but it was my first movie. It was for film school. It was such a long time ago. Now, I’ve made several movies. But it was important for me, because it meant art was a universal thing. My cameraman was a Turkmen guy, my sound man was a Russian guy, et cetera — and we shot in the desert, like Mauritania, and I told a story. And this story of Le jeu was also not my story. But one thing was there. It was my inspiration.

Yes, because it was desert, and deserts are similar. Maybe with some changes. But if you shoot a movie in the desert, you don’t need to show desert. As a filmmaker, you need to cut that, not to show desert. Because it’s not interesting in the cinema. And it’s also the most difficult thing, to shoot a movie in the desert. And I knew that before, and for me it was normal. The most important thing was for me to tell a story in the place where the most important thing will be my character. That is one. The second thing, the place, was also important for me, because I didn’t get the opportunity to shoot my movie in Mauritania. And Turkmenistan was, for me, the only opportunity to do that. And also, the people from there look like Mauritanians, because they are desert people. And it was interesting, but it was my first movie. It was for film school. It was such a long time ago. Now, I’ve made several movies. But it was important for me, because it meant art was a universal thing. My cameraman was a Turkmen guy, my sound man was a Russian guy, et cetera — and we shot in the desert, like Mauritania, and I told a story. And this story of Le jeu was also not my story. But one thing was there. It was my inspiration.

What was your approach to filming October, and creating its interracial dynamic?

When I finished Le jeu, it was my school movie. And I was surprised, because when I showed this movie, it was in Cannes in 1991, and also it was bought by the French TV company, Canal J. I was very surprised. The movie went to different places, and different festivals. And I got the opportunity, and also money, to do another thing where I would have control. I decided to do that, and I decided to make October. Because the story of October is the story of many many people. Not only African people who studied in Russia, in the Soviet Union, but it’s the story of any couple. When you think the love story is not possible for this reason, love doesn’t need a reason. But if the reason exists, it will kill something inside of the people. So, if it’s because she’s not really close to my country — if she comes from Texas and I’m from Africa — something always happens in the human being. But most important in this time, for me, was the only reason for me to leave this country [Russia] where I spent more than 10 years: I know I’m not accepted in this society. It’s sometimes hard to say that. Because if you say, “In the Soviet Union, a Russian guy is like this…” that is not true. It’s not good to judge. But this was really true. And it’s not like if you live in New York, where everybody can be a New Yorker if you decide to be that. But not in Moscow for an African guy. No. And to live in this place where everyday I have the feeling, “It’s not my place. I need to leave, to go somewhere to make cinema to make it.” For that, I decided to

When I finished Le jeu, it was my school movie. And I was surprised, because when I showed this movie, it was in Cannes in 1991, and also it was bought by the French TV company, Canal J. I was very surprised. The movie went to different places, and different festivals. And I got the opportunity, and also money, to do another thing where I would have control. I decided to do that, and I decided to make October. Because the story of October is the story of many many people. Not only African people who studied in Russia, in the Soviet Union, but it’s the story of any couple. When you think the love story is not possible for this reason, love doesn’t need a reason. But if the reason exists, it will kill something inside of the people. So, if it’s because she’s not really close to my country — if she comes from Texas and I’m from Africa — something always happens in the human being. But most important in this time, for me, was the only reason for me to leave this country [Russia] where I spent more than 10 years: I know I’m not accepted in this society. It’s sometimes hard to say that. Because if you say, “In the Soviet Union, a Russian guy is like this…” that is not true. It’s not good to judge. But this was really true. And it’s not like if you live in New York, where everybody can be a New Yorker if you decide to be that. But not in Moscow for an African guy. No. And to live in this place where everyday I have the feeling, “It’s not my place. I need to leave, to go somewhere to make cinema to make it.” For that, I decided to  make a movie. And after I finished this movie, I remember my editor who cut my film, she was a very nice woman — the kind of woman who exists in Russia: simple, beautiful, “like Momma” kind of woman — and also, very cinematographic. When we finished, we edited, and we put some music in to see how the movie would look. And at the first screening, she was there with me. And also my DP, who was Tarkovsky’s DP, Georgi Rerberg. He was a very close friend. When we saw the movie, she told me, “Abderrahmane, I don’t know what happened. But only now do I really understand that maybe your life was really hard in this place.” She hugged me, and she cried. It’s really, really interesting. I learned a lot in Russia. It was hard, but I like the people.

make a movie. And after I finished this movie, I remember my editor who cut my film, she was a very nice woman — the kind of woman who exists in Russia: simple, beautiful, “like Momma” kind of woman — and also, very cinematographic. When we finished, we edited, and we put some music in to see how the movie would look. And at the first screening, she was there with me. And also my DP, who was Tarkovsky’s DP, Georgi Rerberg. He was a very close friend. When we saw the movie, she told me, “Abderrahmane, I don’t know what happened. But only now do I really understand that maybe your life was really hard in this place.” She hugged me, and she cried. It’s really, really interesting. I learned a lot in Russia. It was hard, but I like the people.

What was your relationship with Ousmane Sembène?

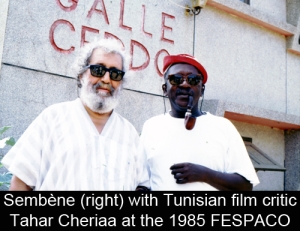

I met him in 1991. It was in Burkina Faso. I was of course very young, and I came from Moscow with Le jeu. It’s very interesting, because I’d go every night with my friend to the nightclub. We left the nightclub around 5-6 o’clock in the morning, and I came back to the hotel at 7 o’clock.  Before I sleep, I prefer to go for breakfast. And Sembene was there early with Tahar Cheriaa, who was the big critic from Tunisia. So I came up to him to say hello, and he was there with 3-4 people. He said, “This guy is really interesting. He woke up very early.” He thought I just woke up. And he said, “I’m sure this guy can go very far.” But he never knew that I just came from the nightclub. That was really funny. And he heard about Le jeu, but he didn’t see it. But he was very interested in me because I studied in Russia, and he also went to Russia. And before this moment, I was accepted at FESPACO at Sembene’s table, where the next youngest person was maybe 60 years old. But I was one of the young filmmakers who Sembene accepted. You can come to say, “Hello”, and he tells you, “Please have a seat.” Of course I would say, “No, no. Thank you, Sembène.” If he insists, you can sit. And it was very interesting, but he played the role of the father. It means he doesn’t need to tell you your movie’s good, or this movie’s not good. No. If you are a young filmmaker, he accepts the art of every young filmmaker. That was the very strong character of Sembène. And the last really important meeting I had with him was when I prepared Bamako. I decided to have Sembène play the role of the “Le procureur.” I called him in Senegal, and on the phone I said, “Sembène, I need to talk with you.

Before I sleep, I prefer to go for breakfast. And Sembene was there early with Tahar Cheriaa, who was the big critic from Tunisia. So I came up to him to say hello, and he was there with 3-4 people. He said, “This guy is really interesting. He woke up very early.” He thought I just woke up. And he said, “I’m sure this guy can go very far.” But he never knew that I just came from the nightclub. That was really funny. And he heard about Le jeu, but he didn’t see it. But he was very interested in me because I studied in Russia, and he also went to Russia. And before this moment, I was accepted at FESPACO at Sembene’s table, where the next youngest person was maybe 60 years old. But I was one of the young filmmakers who Sembene accepted. You can come to say, “Hello”, and he tells you, “Please have a seat.” Of course I would say, “No, no. Thank you, Sembène.” If he insists, you can sit. And it was very interesting, but he played the role of the father. It means he doesn’t need to tell you your movie’s good, or this movie’s not good. No. If you are a young filmmaker, he accepts the art of every young filmmaker. That was the very strong character of Sembène. And the last really important meeting I had with him was when I prepared Bamako. I decided to have Sembène play the role of the “Le procureur.” I called him in Senegal, and on the phone I said, “Sembène, I need to talk with you.  How can I meet you?” He said, “The only possibility is to take a plane to come to me in Dakar.” It was Friday. I said, “I can take the plane Tuesday.” He said, “OK, please come.” And I went. But before, I sent the script to Clarence Delgado, who was Sembène’s assistant. He’s a fantastic guy, a very good person, and a good first assistant. So I sent my script to Clarence to give to Sembène before I came. And I came, and I went to Sembène’s office with Clarence. I said hello to Sembène, and he said hello. He said, “Please have a seat. And Clarence, go out.” And he said, “Clarence tells me you want me to play the role of ‘Le procureur’ in a movie.” I said, “Yes.” He said, “No, it’s not possible. I never act in the movie. But if you want, I can propose a different actor.” And I said, “Yes, of course, Sembène. You can propose it. But I’m not sure if I will take another actor.” It was finished, but we talked, and I went back the next day to Bamako. The role was played by a Malian actor [Magma Gabriel Konaté], and it had very few words. But the figure of Sembène, especially in this movie, for me was very important. Just to see Sembène, and listen what happens, the Sembène figure… it was sad.

How can I meet you?” He said, “The only possibility is to take a plane to come to me in Dakar.” It was Friday. I said, “I can take the plane Tuesday.” He said, “OK, please come.” And I went. But before, I sent the script to Clarence Delgado, who was Sembène’s assistant. He’s a fantastic guy, a very good person, and a good first assistant. So I sent my script to Clarence to give to Sembène before I came. And I came, and I went to Sembène’s office with Clarence. I said hello to Sembène, and he said hello. He said, “Please have a seat. And Clarence, go out.” And he said, “Clarence tells me you want me to play the role of ‘Le procureur’ in a movie.” I said, “Yes.” He said, “No, it’s not possible. I never act in the movie. But if you want, I can propose a different actor.” And I said, “Yes, of course, Sembène. You can propose it. But I’m not sure if I will take another actor.” It was finished, but we talked, and I went back the next day to Bamako. The role was played by a Malian actor [Magma Gabriel Konaté], and it had very few words. But the figure of Sembène, especially in this movie, for me was very important. Just to see Sembène, and listen what happens, the Sembène figure… it was sad.

What’s your take on the conflict between Northern and Southern Mali?

That is a big question. What happened in the North of Mali, before the war when France came, was really something terrible. Not only for Mali, but for the whole region. The reality was for me not six French people who were kidnapped and were somewhere. No. The kidnapped were more than 300-400,000 people from Tombouctou, from Gao, from Kidal they were kidnapping with the system, the vision of the war — the fanatics who say, “You cannot play music. You cannot play football.” If you steal an old bicycle, because you are poor, they can cut off your hand or your foot. That is for a human being today the most terrible thing. Maybe for this reason, my next movie is called “Timbuktu.” It’s possible. I make movies for that. The situation in Mali between North and South is a development question with poverty, of course. If you don’t have the strong political vision on independence day to change something in all parts of the country — if you don’t put in education, if you don’t construct roads — something will happen anywhere. It’s not only the situation that it’s a little White, and a little Dark. No. It’s more complex than that for me.

That is a big question. What happened in the North of Mali, before the war when France came, was really something terrible. Not only for Mali, but for the whole region. The reality was for me not six French people who were kidnapped and were somewhere. No. The kidnapped were more than 300-400,000 people from Tombouctou, from Gao, from Kidal they were kidnapping with the system, the vision of the war — the fanatics who say, “You cannot play music. You cannot play football.” If you steal an old bicycle, because you are poor, they can cut off your hand or your foot. That is for a human being today the most terrible thing. Maybe for this reason, my next movie is called “Timbuktu.” It’s possible. I make movies for that. The situation in Mali between North and South is a development question with poverty, of course. If you don’t have the strong political vision on independence day to change something in all parts of the country — if you don’t put in education, if you don’t construct roads — something will happen anywhere. It’s not only the situation that it’s a little White, and a little Dark. No. It’s more complex than that for me.