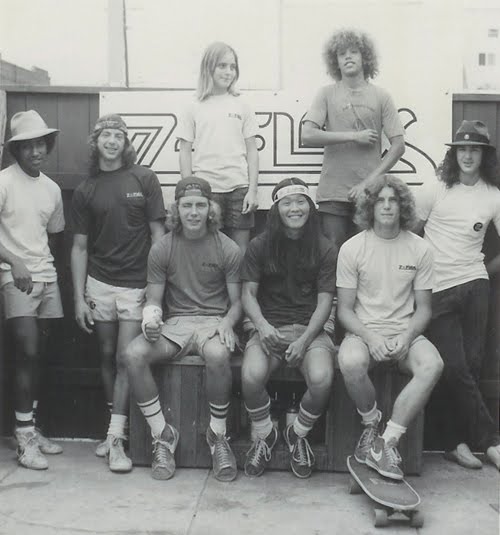

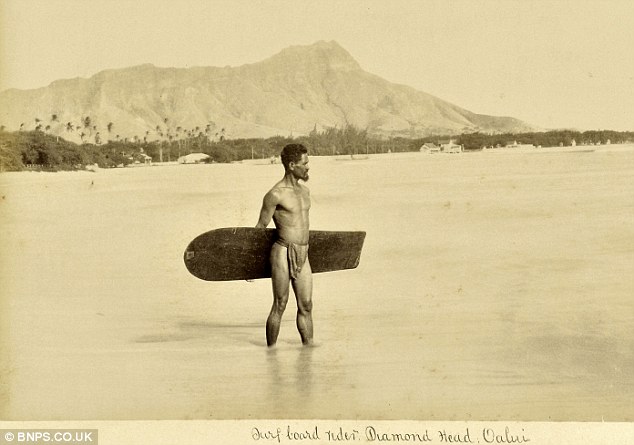

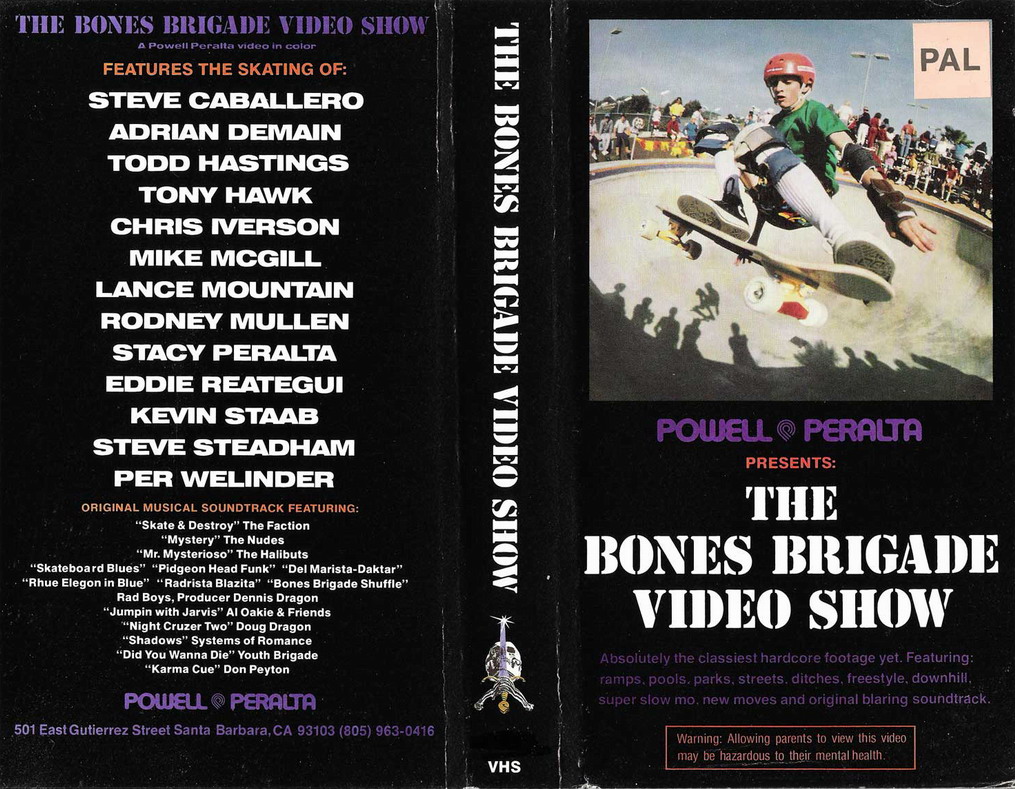

Who: Stacy Peralta is a Los Angeles-based documentary filmmaker who attended local Venice High School as a teen, while also surfing and skateboarding with his friends among the broken piers and sunburned asphalt of the “Dogtown” section of Los Angeles — a territory encompassing the beach communities of South Santa Monica, Venice and Ocean Park. Peralta achieved a professional skateboarding career thanks to time spent on the Zephyr Competition Team (or “Z-Boys”), and parlayed his notoriety into co-founding the Powell Peralta skateboard manufacturing company in 1978, before later pioneering the skateboard video genre by producing and directing The Bones Brigade Video Show in 1984. His 2001 documentary, Dogtown and Z-Boys charts the birth of skateboarding from surfing roots, and the role of Peralta and his former-Zephyr teammates in popularizing the sport worldwide during the 1970’s. 2004’s Riding Giants tracks the evolution of West Coast big-wave surfing culture, beginning in

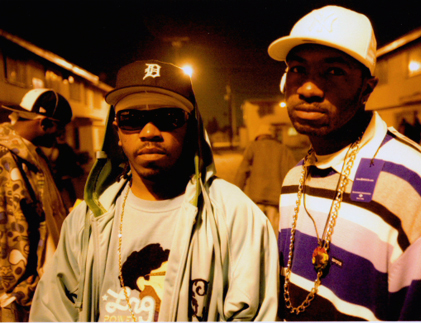

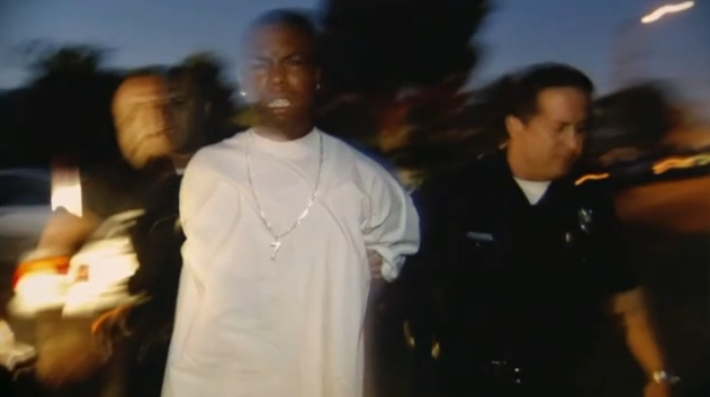

Who: Stacy Peralta is a Los Angeles-based documentary filmmaker who attended local Venice High School as a teen, while also surfing and skateboarding with his friends among the broken piers and sunburned asphalt of the “Dogtown” section of Los Angeles — a territory encompassing the beach communities of South Santa Monica, Venice and Ocean Park. Peralta achieved a professional skateboarding career thanks to time spent on the Zephyr Competition Team (or “Z-Boys”), and parlayed his notoriety into co-founding the Powell Peralta skateboard manufacturing company in 1978, before later pioneering the skateboard video genre by producing and directing The Bones Brigade Video Show in 1984. His 2001 documentary, Dogtown and Z-Boys charts the birth of skateboarding from surfing roots, and the role of Peralta and his former-Zephyr teammates in popularizing the sport worldwide during the 1970’s. 2004’s Riding Giants tracks the evolution of West Coast big-wave surfing culture, beginning in  the 1950’s on Hawaii’s North Shore. Finally, 2009’s Crips & Bloods: Made in America examines how societal factors spawned two of the most notoriously-violent street gangs in the U.S., and the long-term repercussions for the African-American community of South Central Los Angeles, where the gangs live and operate.

the 1950’s on Hawaii’s North Shore. Finally, 2009’s Crips & Bloods: Made in America examines how societal factors spawned two of the most notoriously-violent street gangs in the U.S., and the long-term repercussions for the African-American community of South Central Los Angeles, where the gangs live and operate.

[Publisher’s Note: Special thanks to the staff at Nonfiction Unlimited]

As a native resident, what do you think are some misconceptions about L.A. held by non-locals?

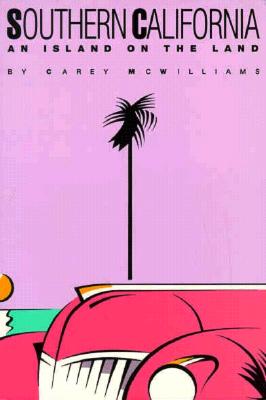

When we were growing up here in the ’70’s, whenever people from the East Coast would come here, they would always remark on how the place is empty of culture — that it was a wasteland. Very often you heard this term: “When you’re looking in front of you, you see the ocean. When you look behind you, you see the desert. And there’s nothing between.” But what those people didn’t realize is there was a vibrant culture. They just couldn’t recognize it, because it didn’t look like what things look like on the East Coast. And now, looking back thirty years later, we can see, my God, there really was a culture and that culture’s now being embraced by the world. L.A.’s always been a Hollywood backdrop for everything. It’s just par for the course. It’s what makes it real and unreal at the same time. It’s a place that’s realer than real. If you really want to take it to another level, you have to go back to Carey McWilliams’ book, Southern California: An Island on the Land, which basically states that Southern California’s a desert. It’s not supposed to have people living in it, but because we brought water to it, we were able to create something. So, in a sense, [L.A.] is just as big a mirage as the movies, because it’s not

When we were growing up here in the ’70’s, whenever people from the East Coast would come here, they would always remark on how the place is empty of culture — that it was a wasteland. Very often you heard this term: “When you’re looking in front of you, you see the ocean. When you look behind you, you see the desert. And there’s nothing between.” But what those people didn’t realize is there was a vibrant culture. They just couldn’t recognize it, because it didn’t look like what things look like on the East Coast. And now, looking back thirty years later, we can see, my God, there really was a culture and that culture’s now being embraced by the world. L.A.’s always been a Hollywood backdrop for everything. It’s just par for the course. It’s what makes it real and unreal at the same time. It’s a place that’s realer than real. If you really want to take it to another level, you have to go back to Carey McWilliams’ book, Southern California: An Island on the Land, which basically states that Southern California’s a desert. It’s not supposed to have people living in it, but because we brought water to it, we were able to create something. So, in a sense, [L.A.] is just as big a mirage as the movies, because it’s not  supposed to be there. But we made it here.

supposed to be there. But we made it here.

The only films to me that really have depicted L.A. the way I know it, are [director, Quentin] Tarantino’s films. He shows elements of L.A. that are just so L.A., they’re like nothing else. There’s just nowhere else like it in the world. And I say specifically, in Pulp Fiction, there is a scene where Bruce Willis’ character is walking through this field of dead grass on the way to an apartment. And just seeing that dead grass, and that empty lot, and then when he gets to that apartment, and that stucco box-style of apartment building with the atrium stairs in the middle of it — it was just like, “oh my God, only in California.” It was just captured so beautifully. Not a key piece of the movie, but he got it right.

Were any Crips and Bloods you talked to worried about a white director getting their story right?

No, and I thought there was going to be lots, and there wasn’t. In fact, it was the other way around. I had people thanking me for coming to their neighborhood, thanking me for spending the time to tell their story — and I never expected that. I thought they were going to look at me like, “Who are you?” and “What do you want? We don’t want you here.” But that’s not the way it was at all. They were like, “Hey, don’t be a stranger.” They know how bad their situation is. They want their story told — even the worst of them — but I approached them as a person first, and I didn’t ask them demeaning questions. Because they told me a lot of times, when newspaper reporters would come in there, they would ask really demeaning things like, “Hey, can I watch you do your next drive-by, so I can document it?” You know, one reporter that had been there prior to my arrival, he actually had a death threat put on his head because he’d been so disrespectful to them. I never went in with that. In fact, before I even shot a role of film,

No, and I thought there was going to be lots, and there wasn’t. In fact, it was the other way around. I had people thanking me for coming to their neighborhood, thanking me for spending the time to tell their story — and I never expected that. I thought they were going to look at me like, “Who are you?” and “What do you want? We don’t want you here.” But that’s not the way it was at all. They were like, “Hey, don’t be a stranger.” They know how bad their situation is. They want their story told — even the worst of them — but I approached them as a person first, and I didn’t ask them demeaning questions. Because they told me a lot of times, when newspaper reporters would come in there, they would ask really demeaning things like, “Hey, can I watch you do your next drive-by, so I can document it?” You know, one reporter that had been there prior to my arrival, he actually had a death threat put on his head because he’d been so disrespectful to them. I never went in with that. In fact, before I even shot a role of film,  I went in there alone to meet everybody and say, “Look, this is who I am. This is what I wanna do, and I’m looking for your approval, and I’m looking for you to be involved in this, and I want your involvement. What do I have to do to make that happen?” And they really appreciated that, because they’re not used to people treating them that way.

I went in there alone to meet everybody and say, “Look, this is who I am. This is what I wanna do, and I’m looking for your approval, and I’m looking for you to be involved in this, and I want your involvement. What do I have to do to make that happen?” And they really appreciated that, because they’re not used to people treating them that way.

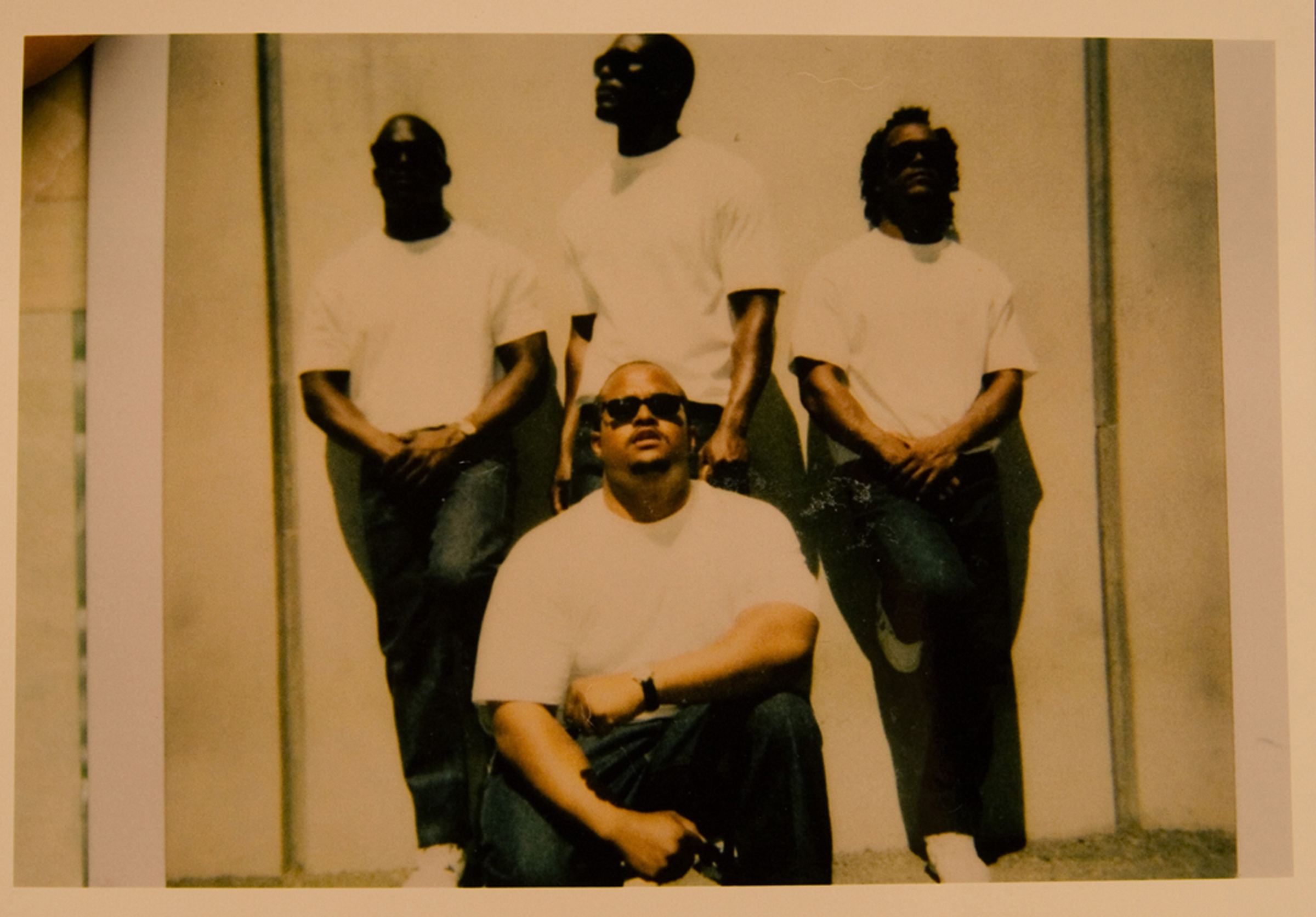

A lot of people ask me, “How did you get these guys — many of them killers — to sit down and talk with you?” One of the things that I understood from surfing, that when you go into another person’s territory, that territory belongs to them. You have to show them respect. You have to carry yourself a certain way, and you have to aim everything that you’re trying to get from them in a way that shows you respect them — that you respect where they’re from, and you respect their rules. But also, let me tell you something, this entire thing — whether it’s Dogtown, Riding Giants or Made in America — it is all about identity. It’s all about wanting to belong to something as a young male. It’s super-duper important. [I] wanted to belong to skateboarding and surfing. The big wave riders that I focused on in Riding Giants, they wanted to be surfers when it wasn’t a cool thing to be. And these gang guys,  they know what they do is wrong, but they want to belong to something that gives them some sort of identity and self-esteem.

they know what they do is wrong, but they want to belong to something that gives them some sort of identity and self-esteem.

The problem is, when people look at current gang members, they think one thing: “these kids are monsters. They’re just born monsters.” And they’re not. And so, you have to understand what preceded this, what led up to this. And that’s why we focus on the birth of [’60’s Watts gang] “The Slausons,” and it’s also why we focused on the migration of African-American people from the South to places like Los Angeles in the ’30’s and during World War II. Because when you see how they were penned in, and they weren’t allowed (through real estate covenants) to move out, so they ended up living on top of each other — knowing that it was good somewhere else, but not where they were. You know, we wonder why it’s bad there. Well, it’s bad because we set it up that way, and it was also a police state.  It’s not like that in white neighborhoods, but it is like that in those neighborhoods. And it affects people’s self-esteem, and how they feel about themselves and their community, and how they feel about each other.

It’s not like that in white neighborhoods, but it is like that in those neighborhoods. And it affects people’s self-esteem, and how they feel about themselves and their community, and how they feel about each other.

You really have to talk to those who live in the area. And I can only tell you, when I talked to those people, they said that it’s still very difficult. They’re still preyed upon. They’re still looked at as guilty before they do things. They are constantly put up against the hoods of cars and checked, just for like a power deal, so they can be reminded of who’s in charge. Is it as bad as it was, you know, in the ’40’s and ’50’s? I doubt it, because that’s just been completely brought to light now. But when I was in those communities, I saw police in a way I’d never seen before — helicopters, sirens, cars all the time. There’s just a very heavy presence.

How did past non-fiction media coverage of this community affect your decision to document it?

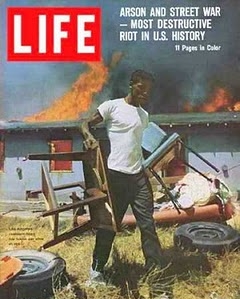

I was a very young kid during the ’65 riots, and I remember watching it on TV. I didn’t understand it, because I was too young, but I remember people were concerned about it. The neighborhood was concerned about it. Now, I was an adult during ’92, and I couldn’t understand how two of the strongest civil rebellions in America could literally happen within miles of each other, 27 years apart — just didn’t make any sense to me. And that’s one of the reasons I wanted to make the film, because I wanted to understand it better. Why did this happen again? And how did it happen again? And if it did happen again, there must be something very serious going on here.

I was a very young kid during the ’65 riots, and I remember watching it on TV. I didn’t understand it, because I was too young, but I remember people were concerned about it. The neighborhood was concerned about it. Now, I was an adult during ’92, and I couldn’t understand how two of the strongest civil rebellions in America could literally happen within miles of each other, 27 years apart — just didn’t make any sense to me. And that’s one of the reasons I wanted to make the film, because I wanted to understand it better. Why did this happen again? And how did it happen again? And if it did happen again, there must be something very serious going on here.

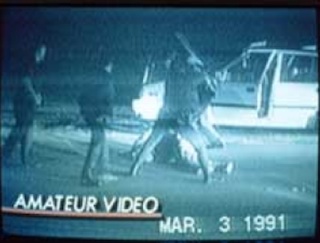

The incident that Rodney King went through, getting beaten the way he got beaten by the police — which was illegal — had it not been covered on video, then that would never have been uncovered, and nothing subsequently resulting from that would have been brought to light. So much anger exploded because of that, because so much of that had been happening. When you go to South Los Angeles, people will tell you  that kind of stuff happens all the time, but it was that one time that it got caught on video, so the world could see how they had been treated. And they justifiably got very angry when all those police got off, because to them this happens all the time, and they feel it’s wrong in this country to happen like that. People now have video cameras on their phones, and look what’s happening in the Middle East right now. The governments are shutting down the internet, yet people are shooting videos on their phones, and they’re texting these videos to other people, who are sending them out. The information in peoples hands now is being shared to people very far away, so the world can see exactly the injustices that are happening elsewhere. Is it gonna make this a better world? Well, let’s hope so.

that kind of stuff happens all the time, but it was that one time that it got caught on video, so the world could see how they had been treated. And they justifiably got very angry when all those police got off, because to them this happens all the time, and they feel it’s wrong in this country to happen like that. People now have video cameras on their phones, and look what’s happening in the Middle East right now. The governments are shutting down the internet, yet people are shooting videos on their phones, and they’re texting these videos to other people, who are sending them out. The information in peoples hands now is being shared to people very far away, so the world can see exactly the injustices that are happening elsewhere. Is it gonna make this a better world? Well, let’s hope so.

How culturally isolated is this community from the rest of Los Angeles?

They don’t often see the outside world coming into their community, because for the outside world there’s no first-class restaurants, there’s no theme parks, there’s no health clubs, there’s no Whole Foods. So, there isn’t really a reason, unfortunately, for others to come inside that community. They’re stagnated there. They remain stagnated. And they know it. You can see the Hollywood Hills from South L.A., and I had a guy tell me one day, he goes, “That might as well just be another planet to us,

They don’t often see the outside world coming into their community, because for the outside world there’s no first-class restaurants, there’s no theme parks, there’s no health clubs, there’s no Whole Foods. So, there isn’t really a reason, unfortunately, for others to come inside that community. They’re stagnated there. They remain stagnated. And they know it. You can see the Hollywood Hills from South L.A., and I had a guy tell me one day, he goes, “That might as well just be another planet to us,  because we’re never getting there.”

because we’re never getting there.”

In Dogtown, probably half the team grew up with their mothers. They didn’t have fathers. But the big difference here is these young men who are growing up in South Central Los Angeles, who don’t have fathers, that’s the norm. Meaning that probably 9/10ths of their friends also don’t have fathers. No one on their street has fathers. And so, they’re growing up in a “fatherless society.” That wasn’t the case with Dogtown. Yes, there were fathers missing, but it wasn’t like that was the predominant sociological thing in Dogtown, in Santa Monica in that time. But in South Central, it is that way. The fathers are either dead, either gone or they’re in jail. And you’re talking about generations of this. It becomes normal not to have a father. And that’s not normal.

I think the African American population makes up 12% of the population of this country. But they are over 50% of the people in jail. I mean, that’s a crime in itself, that statistic. There’s no larger group of incarcerated men than black men. And also, whenever you look at the unemployment figures, it’s always 20% worse for black men across the board. So, we have to look at these statistics realistically. No one wants to, but we have to, because this isn’t gonna get better. It’s gonna get worse. And at some point it’s gonna leave that community, and come into the communities that don’t want it.

I think the African American population makes up 12% of the population of this country. But they are over 50% of the people in jail. I mean, that’s a crime in itself, that statistic. There’s no larger group of incarcerated men than black men. And also, whenever you look at the unemployment figures, it’s always 20% worse for black men across the board. So, we have to look at these statistics realistically. No one wants to, but we have to, because this isn’t gonna get better. It’s gonna get worse. And at some point it’s gonna leave that community, and come into the communities that don’t want it.

Something hit me one day. If affluent white kids growing up in Beverly Hills started arming themselves with AK-47’s, and they started shooting at affluent white kids who lived in Brentwood, who also were arming themselves, what do you think would be the reaction of our government? Everybody I  posed that question to said the same thing: It’d be over in one day. Government would never allow it to happen. Why is it that, with young African Americans, this has been going on for 30 years? We can survive World War II and win it, but we can’t win gang violence? Are you kidding me? So it seemed to me that there was a form of structural racism. If you read Michael Dyson’s books, he explains this concept of structural racism, where the community in which these kids grow up is against them from the start. They have lesser opportunities at employment. They have lesser opportunities in education. They are preyed upon by police, and so they grow up in a different form of this country than we know. But no one knows this, because they don’t go into those areas, so they remain like this decade after decade. And these kids are suffering.

posed that question to said the same thing: It’d be over in one day. Government would never allow it to happen. Why is it that, with young African Americans, this has been going on for 30 years? We can survive World War II and win it, but we can’t win gang violence? Are you kidding me? So it seemed to me that there was a form of structural racism. If you read Michael Dyson’s books, he explains this concept of structural racism, where the community in which these kids grow up is against them from the start. They have lesser opportunities at employment. They have lesser opportunities in education. They are preyed upon by police, and so they grow up in a different form of this country than we know. But no one knows this, because they don’t go into those areas, so they remain like this decade after decade. And these kids are suffering.

I think [Hollywood depictions] help promote the idea that these are just bad kids — that they’re just born bad. And I think it allows people to hold a bit of racism within themselves, because they can look at those kids from a distance without really knowing the truth and go, “Yeah, they are bad. They don’t deserve anything. They deserve to be in jail.” And it just takes the compassion card out, which I think is so important in this case. Because what I found when I was making the film, was that these kids aren’t even looked at as being Americans. They’re looked at as some other form — that they almost don’t belong in this country — and that’s the way I felt people looked at them. You know, when I was making the film, so many people said, “Why do you want to make a film about those guys?” You know, as a country, we don’t understand the struggles of these poor people, and it’s awful what they’re struggling through. No kid is born into this world

I think [Hollywood depictions] help promote the idea that these are just bad kids — that they’re just born bad. And I think it allows people to hold a bit of racism within themselves, because they can look at those kids from a distance without really knowing the truth and go, “Yeah, they are bad. They don’t deserve anything. They deserve to be in jail.” And it just takes the compassion card out, which I think is so important in this case. Because what I found when I was making the film, was that these kids aren’t even looked at as being Americans. They’re looked at as some other form — that they almost don’t belong in this country — and that’s the way I felt people looked at them. You know, when I was making the film, so many people said, “Why do you want to make a film about those guys?” You know, as a country, we don’t understand the struggles of these poor people, and it’s awful what they’re struggling through. No kid is born into this world  wanting to pick up a gun. It’s something that’s conditioned into them. They’re conditioned like that, and if they aren’t tough, they get taken down. They don’t have a lot of choices, and so what happens is it hardens them, and they have to be tough, and they have to be bullies back. And so, that terribly affects their life. I think most of the kids in there that are involved in gang violence, I think they’re suffering from post-traumatic stress disorder.

wanting to pick up a gun. It’s something that’s conditioned into them. They’re conditioned like that, and if they aren’t tough, they get taken down. They don’t have a lot of choices, and so what happens is it hardens them, and they have to be tough, and they have to be bullies back. And so, that terribly affects their life. I think most of the kids in there that are involved in gang violence, I think they’re suffering from post-traumatic stress disorder.

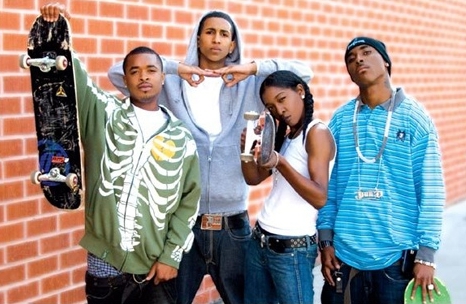

How have gang fashions and growing racial diversity affected skateboard fashions and culture?

When I went to Venice High School, the Latino gangs used to wear the same exact thing that we surfers wore, but they wore it differently. We wore baggy Levis or Pinwheel cords, t-shirts and like a long button-down Pendleton, and these shoes called Winos. Well, the Latino and the African-American gangs, they wore the same exact thing we wore, except theirs were starch-pressed. They were perfect. They were absolutely perfect. They hung on them perfectly. And they really put a tremendous amount of time into how they looked. I mean, there was creases in their pants. So, it’s just a different approach, but all influenced by the same thing. All sharing the same space, but defining it differently, and looking for a separate identity. And then, what happened is in the late-80’s, early 90’s when street skateboarding became very popular, there was a real symbiosis between inner-city gang life and skateboarding, where they were literally wearing the same clothes.

When I went to Venice High School, the Latino gangs used to wear the same exact thing that we surfers wore, but they wore it differently. We wore baggy Levis or Pinwheel cords, t-shirts and like a long button-down Pendleton, and these shoes called Winos. Well, the Latino and the African-American gangs, they wore the same exact thing we wore, except theirs were starch-pressed. They were perfect. They were absolutely perfect. They hung on them perfectly. And they really put a tremendous amount of time into how they looked. I mean, there was creases in their pants. So, it’s just a different approach, but all influenced by the same thing. All sharing the same space, but defining it differently, and looking for a separate identity. And then, what happened is in the late-80’s, early 90’s when street skateboarding became very popular, there was a real symbiosis between inner-city gang life and skateboarding, where they were literally wearing the same clothes.

The big deal was that I went to integrated schools. My junior high and high school were White, Black, Latino, Jewish, Asian — everybody. I didn’t go to like a school in Santa Barbara, or somewhere like that, where it’s all protected. You know, I went to inner-city schools, and so that’s what I was around. Was I friends with those guys at school? Not necessarily, but it was normal thing for me. So when we had guys like that on the team, although you didn’t find that outside of Los Angeles — having Asians or Mexicans or African Americans on a skateboard or surf team — you did find that in Los Angeles.

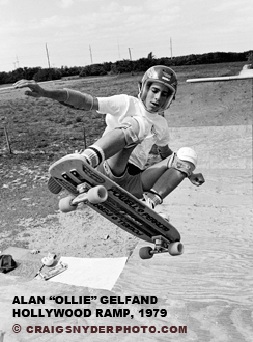

There’s been a dramatic — and I mean dramatic — increase in African-American skaters and Latino skaters. And it happened in the early ’90’s, and it happened for this reason: in the ’80’s, if you looked in a magazine, skating was based on vertical skateboarding. That was the primary thing that the magazines covered. And in the late-’80’s, a new form of skating emerged called street skating. And part of the reason this new form emerged was because of the “ollie” — that you could ollie down stairs and up stairs. You could ollie onto the sides of buildings. You ollie onto a hand railing. And so, it opened up this brand new form of skating, so all these inner-city kids who could not afford to get to the skateboard park or could not afford a skateboard ramp, they could street skate. And all of sudden, the color barrier of skateboarding was completely opened up. And now when you see skateboarding, and you see skateboarders, it looks nothing like it used to look in my day. And it’s completely left its surfing roots, and its become its own thing. It’s completely divorced of surfing, and it’s very ethnic, and to me that’s where it finally came into its own. That’s where it finally found itself what it wanted to be.

There’s been a dramatic — and I mean dramatic — increase in African-American skaters and Latino skaters. And it happened in the early ’90’s, and it happened for this reason: in the ’80’s, if you looked in a magazine, skating was based on vertical skateboarding. That was the primary thing that the magazines covered. And in the late-’80’s, a new form of skating emerged called street skating. And part of the reason this new form emerged was because of the “ollie” — that you could ollie down stairs and up stairs. You could ollie onto the sides of buildings. You ollie onto a hand railing. And so, it opened up this brand new form of skating, so all these inner-city kids who could not afford to get to the skateboard park or could not afford a skateboard ramp, they could street skate. And all of sudden, the color barrier of skateboarding was completely opened up. And now when you see skateboarding, and you see skateboarders, it looks nothing like it used to look in my day. And it’s completely left its surfing roots, and its become its own thing. It’s completely divorced of surfing, and it’s very ethnic, and to me that’s where it finally came into its own. That’s where it finally found itself what it wanted to be.

Why was the development of the urethane wheel so important to skateboarding?

The urethane wheel was as game-changing for skateboard as the Conestoga wagon to the automobile. It was that radical. Meaning that, prior to the urethane wheel, we essentially were skating on round rocks. We were skating on what you’d assume Fred Flintstone would have skateboarded on. That’s what it was like. There was no grip. They were rock-hard. If you went over a bump or a pebble, the board would stop, and you’d fall off it and get hurt. I mean, it was just terrible. And you were very limited to the surfaces that you could ride. You really couldn’t ride a pool, because it was too slippery. And so, when the urethane wheel came in, it was like riding on a radial tire. It gripped, you could turn hard, you could all of a sudden ride vertical surfaces. You could bounce off of things and stay on your board. You could run over rocks. It was phenomenal. It changed the whole thing. It made modern skateboarding possible. Without it, there would be no modern skateboarding.

The urethane wheel was as game-changing for skateboard as the Conestoga wagon to the automobile. It was that radical. Meaning that, prior to the urethane wheel, we essentially were skating on round rocks. We were skating on what you’d assume Fred Flintstone would have skateboarded on. That’s what it was like. There was no grip. They were rock-hard. If you went over a bump or a pebble, the board would stop, and you’d fall off it and get hurt. I mean, it was just terrible. And you were very limited to the surfaces that you could ride. You really couldn’t ride a pool, because it was too slippery. And so, when the urethane wheel came in, it was like riding on a radial tire. It gripped, you could turn hard, you could all of a sudden ride vertical surfaces. You could bounce off of things and stay on your board. You could run over rocks. It was phenomenal. It changed the whole thing. It made modern skateboarding possible. Without it, there would be no modern skateboarding.  It wouldn’t exist.

It wouldn’t exist.

There’s been enhancements, but they weren’t as revolutionary as that. You know, there were enhancements like boards went from being six inches wide to nine inches wide — which was a big deal, but it wasn’t revolutionary. There’s been enhancements in terrain, where we used to ride half pipes that were a complete “U.” And what we did is, we finally realized this is not right. We have to pull the bottom out. The idea was to develop flat bottom between those sides of the walls. That was a really revolutionary thing, but none of this compares to the wheel. But I will say one thing — there was one maneuver that was invented that you could almost say is as important as the urethane wheel itself, and that’s the ollie. The ollie as a trick was the most important trick invented in the 20th Century, and it will always be the most important trick. Because it’s not only a trick, it’s a technique. If you play ball, it’s the swing of the bat. It just has become everything to skateboarding. It was one of the guys on my skateboard team, a kid named Alan “Ollie” Gelfand — a little Jewish kid from Florida — he developed the ollie in Florida. And then another kid on my team, Rodney Mullen, developed it even further. So, it has it’s source from two Floridian skaters.

Was there resentment among Hawaiians over white mainland surfers invading the North Shore?

I think there certainly has been over time. I think it got more pronounced in the later years, as more and more white people came to the North Shore, later than we covered. Yeah, it did become much more pronounced, like, “Hey, you’re wrecking our place.” And also that they lost their language, do to America coming in and making Hawaii a state, so that was a problem. But it wasn’t for the early [white surfers] that we covered. There weren’t that many. There was just a few of them, so they weren’t really causing any problems. And also, to be honest with you, the areas that they were surfing — the North Shore — that was primarily, believe it or not, a Chinese area. You know, it was a farming area, so a lot of Chinese people lived there. And remember, it was before Hawaii even became a state when they started going there, so it was like going to Indonesia today. It was a very far away place, and the flights to get there, I think, were 8 or 10 hours in the air.

I think there certainly has been over time. I think it got more pronounced in the later years, as more and more white people came to the North Shore, later than we covered. Yeah, it did become much more pronounced, like, “Hey, you’re wrecking our place.” And also that they lost their language, do to America coming in and making Hawaii a state, so that was a problem. But it wasn’t for the early [white surfers] that we covered. There weren’t that many. There was just a few of them, so they weren’t really causing any problems. And also, to be honest with you, the areas that they were surfing — the North Shore — that was primarily, believe it or not, a Chinese area. You know, it was a farming area, so a lot of Chinese people lived there. And remember, it was before Hawaii even became a state when they started going there, so it was like going to Indonesia today. It was a very far away place, and the flights to get there, I think, were 8 or 10 hours in the air.

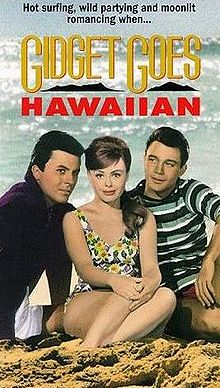

Which surfing film played the largest part in growing the sport — and which one was the best?

Endless Summer was really made for surfers, and although it crossed over, it was really Gidget that caused the big explosion. Because I think we say in the film, prior to Gidget there was maybe a million surfers in all of the United States, and after Gidget I think there was five million. It was gigantic, the shift. It was huge. The film just had a gigantic effect.

Endless Summer was really made for surfers, and although it crossed over, it was really Gidget that caused the big explosion. Because I think we say in the film, prior to Gidget there was maybe a million surfers in all of the United States, and after Gidget I think there was five million. It was gigantic, the shift. It was huge. The film just had a gigantic effect.

Every single [fictional] surf movie that’s come along has not worked. There’s only been one surfing sequence in a film that has represented surfing properly, and that was in Apocalypse Now. You’re dealing with Colonel Kilgore, played by Robert Duvall, and he’s a hardcore surfer, and he discovers that in his platoon is a famous surfer named Lance. And he decides, “I wanna see this guy, that I’ve heard about all my life, surf.” And so, they’re gonna go bomb this village, because they know there’s surf there. And they’re gonna do it, and they’re gonna risk their lives — and to be honest with you, that’s how fanatical surfers are. And I know it probably seems over-the-top, and it probably is over-the-top, but that is the one scene in all surfing  movies — Hollywood movies — that actually got it right.

movies — Hollywood movies — that actually got it right.

[Apocalypse Now writer] John [Milius] was a good surfer. He could actually surf really well, and so he grew up wanting to somehow put surfing in one of his movies. It meant that much to him. It still means that much to him. Putting him in Riding Giants meant so much to him, and he was so happy to be a part of it. One of his heroes is Greg Noll. So yeah, what happens is, once you’ve been a surfer, it never leaves you.

[Milius’ parents] thought it was a waste of time, because there was no scoreboard. There was nothing to take from it, so it seemed like a big waste of time. And that’s how everybody felt. I’ve  struggled with that my whole life — not only with surfing, but skateboarding was even worse. It’s like, “What’s the point of this?” And especially considering that “skateboarding” didn’t even exist when we were doing it. Before the urethane wheel was invented, as far as we knew, we were the only people on Earth doing it in my little neighborhood, because there was no such thing as a store or a place you could go buy them. It was a dead sport. It was a past fad. It was gone. So, it was really looked down upon.

struggled with that my whole life — not only with surfing, but skateboarding was even worse. It’s like, “What’s the point of this?” And especially considering that “skateboarding” didn’t even exist when we were doing it. Before the urethane wheel was invented, as far as we knew, we were the only people on Earth doing it in my little neighborhood, because there was no such thing as a store or a place you could go buy them. It was a dead sport. It was a past fad. It was gone. So, it was really looked down upon.

What was your role in televising the ’80’s skateboard revolution?

I’m credited as starting the whole skateboard video revolution. I made the very first series of skateboard videos in the ’80’s. And we started doing it simply because we were trying to figure out a way to show skateboarders around the world how it’s done, and we wanted to promote our skateboard team. And we never expected to sell these to kids. We just assumed we’d sell a handful of them to stores, you know, to skateboard shops. But we also didn’t realize that by the late ’80’s, 70% of the American households would own a VCR. And so these films I made went all over the world, and they acted as this kind of information revolution for skateboarding. They became manifestos. What’s happened to skateboarding videos since that time, is they’ve just simply become action porn. There’s no story. There’s no context. It’s just basically an inventory of tricks, one after the other, after the other. It doesn’t even really show kids skateboarding. It just shows them doing the exclamation point. And the kids that even like these videos will tell you the same thing. There’s no story. It’s just porn.

I’m credited as starting the whole skateboard video revolution. I made the very first series of skateboard videos in the ’80’s. And we started doing it simply because we were trying to figure out a way to show skateboarders around the world how it’s done, and we wanted to promote our skateboard team. And we never expected to sell these to kids. We just assumed we’d sell a handful of them to stores, you know, to skateboard shops. But we also didn’t realize that by the late ’80’s, 70% of the American households would own a VCR. And so these films I made went all over the world, and they acted as this kind of information revolution for skateboarding. They became manifestos. What’s happened to skateboarding videos since that time, is they’ve just simply become action porn. There’s no story. There’s no context. It’s just basically an inventory of tricks, one after the other, after the other. It doesn’t even really show kids skateboarding. It just shows them doing the exclamation point. And the kids that even like these videos will tell you the same thing. There’s no story. It’s just porn.

Your films are known for great soundtracks – do you worry about music overshadowing story?

Sometimes I worry about the editing style that I use overshadows the story, and maybe I should back off. But as far as music goes, I put so much effort into the music in these films that it keeps me from wanting to make more films, because just putting that soundtrack together is such a job. You’re talking about 45 to 50 pieces of music, which means I have to go through probably 500 songs to find that. Like, I’m making a film right now — I just started a new film — and the first thing I started doing, before I even started shooting, before I even started to construct the film in my head, is I started building the soundtrack. And the reason I built the soundtrack first, is that it enables me to feel and hear and touch what the film wants to be. I get these feelings, and there’s certain pieces of music that I hear, and I go, “Oh yeah, that’s right. This has to be in the film.” And it’s my starting point. It sets the emotional tone for me for what the film should be. And each film I start off with, I always have five songs I’m holding onto. Let’s say, of the 200 songs I begin with, there’s typically 5 to 10 that I know will make it in the film, because I have such a strong gut feeling for them.

Sometimes I worry about the editing style that I use overshadows the story, and maybe I should back off. But as far as music goes, I put so much effort into the music in these films that it keeps me from wanting to make more films, because just putting that soundtrack together is such a job. You’re talking about 45 to 50 pieces of music, which means I have to go through probably 500 songs to find that. Like, I’m making a film right now — I just started a new film — and the first thing I started doing, before I even started shooting, before I even started to construct the film in my head, is I started building the soundtrack. And the reason I built the soundtrack first, is that it enables me to feel and hear and touch what the film wants to be. I get these feelings, and there’s certain pieces of music that I hear, and I go, “Oh yeah, that’s right. This has to be in the film.” And it’s my starting point. It sets the emotional tone for me for what the film should be. And each film I start off with, I always have five songs I’m holding onto. Let’s say, of the 200 songs I begin with, there’s typically 5 to 10 that I know will make it in the film, because I have such a strong gut feeling for them.

It’s always a challenge. [For Dogtown,] even though it was all ’70’s-centric music, we had to find the right one — the right piece. Riding Giants was tough, because we covered three different time [periods]. That was tricky. Crips & Bloods, we covered a lot of time. I had to have music for the Slausons, I had to have music for the ’30’s and ’40’s, and I had to have contemporary music — and then, I had to have music that went under post-traumatic stress disorder. So, it’s a tall order. But, as I said, it’s the music that leads me where I need to go.