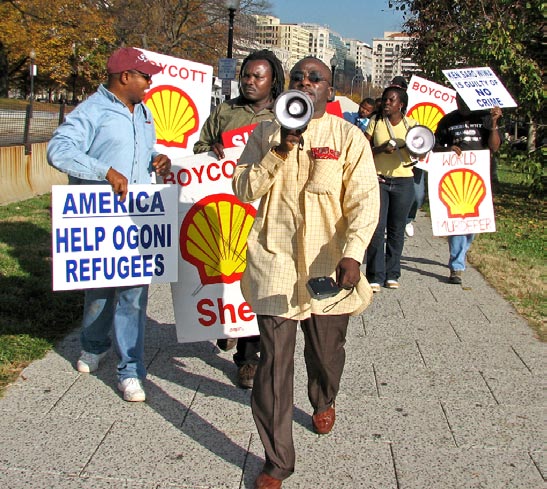

Who: Zina Saro-Wiwa is a Nigerian-born and New York-based documentary filmmaker whose production company, AfricaLab made the recent HBO documentary This is My Africa. The AfricaLab-produced art exhibition, “Sharon Stone in Abuja” featured her two short films, The Deliverance of Comfort and Phyllis, and deconstructs the Nigerian film industry (known as Nollywood) that annually produces 1000-1,500 home video films, and an estimated annual cash take of over $320 million. That massive number of Nigerian-made films exceeds the American Hollywood and Indian Bollywood film industries. Saro-Wiwa previously lived and worked in England, and from 2004 to 2008 was a presenter for BBC2’s The Culture Show, in addition to producing and researching for BBC TV and radio. Her father, Ken Saro-Wiwa was an author who produced the Nigerian television program Basi and Company from 1985-90, before turning to political advocacy in the 1990’s to protest environmental devastation in his home region of Ogoniland, within the oil-rich Niger Delta, by Royal Dutch Shell. On November 10th, 1995, he and eight other Ogoni activists

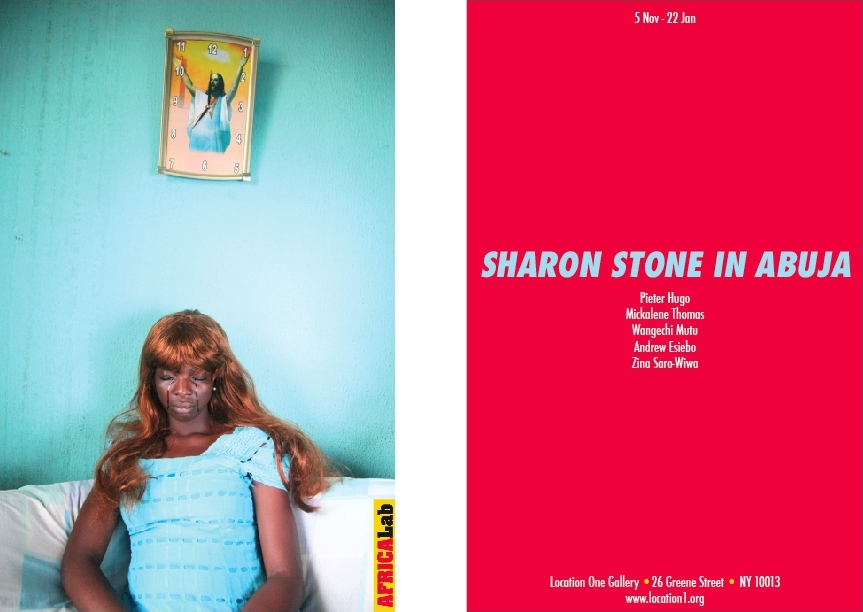

Who: Zina Saro-Wiwa is a Nigerian-born and New York-based documentary filmmaker whose production company, AfricaLab made the recent HBO documentary This is My Africa. The AfricaLab-produced art exhibition, “Sharon Stone in Abuja” featured her two short films, The Deliverance of Comfort and Phyllis, and deconstructs the Nigerian film industry (known as Nollywood) that annually produces 1000-1,500 home video films, and an estimated annual cash take of over $320 million. That massive number of Nigerian-made films exceeds the American Hollywood and Indian Bollywood film industries. Saro-Wiwa previously lived and worked in England, and from 2004 to 2008 was a presenter for BBC2’s The Culture Show, in addition to producing and researching for BBC TV and radio. Her father, Ken Saro-Wiwa was an author who produced the Nigerian television program Basi and Company from 1985-90, before turning to political advocacy in the 1990’s to protest environmental devastation in his home region of Ogoniland, within the oil-rich Niger Delta, by Royal Dutch Shell. On November 10th, 1995, he and eight other Ogoni activists  were executed by the then-government led by General Sani Abacha. This is My Africa premiered on HBO in February of 2010, while Phyllis and The Deliverance of Comfort (two experimental Nollywood short films) are screening at Lincoln Center in Manhattan as part of the 18th New York African Film Festival. On April 2nd, before a screening of the 1966 Soviet documentary African Rhythmus (chronicling the First World Festival of Negro Arts in Dakar, Senegal) at the Museum of Arts and Design, Zina appeared on a panel with Harry Belafonte to discuss the power and role of art in the black diaspora.

were executed by the then-government led by General Sani Abacha. This is My Africa premiered on HBO in February of 2010, while Phyllis and The Deliverance of Comfort (two experimental Nollywood short films) are screening at Lincoln Center in Manhattan as part of the 18th New York African Film Festival. On April 2nd, before a screening of the 1966 Soviet documentary African Rhythmus (chronicling the First World Festival of Negro Arts in Dakar, Senegal) at the Museum of Arts and Design, Zina appeared on a panel with Harry Belafonte to discuss the power and role of art in the black diaspora.

[Publisher’s Note: Special thanks to the staff at The Film Society of Lincoln Center, and Cheryl Duncan PR]

Who is the person most responsible for the current Nollywood style and direct-to-video format?

The birth of the Nollywood industry is often attributed to a man called Kenneth Nnebue. He was a video salesman, and he wanted to sell a consignment of blank tapes he had on his hands from Taiwan. He was having trouble selling them, so he thought he’d put something on them to help shift some stock. And that’s basically what he did. The first Nollywood films, in a sense, were kind of Yoruba street theater on video. You can see the seeds of Nollywood’s style here. Yoruba street theater is so much of the environment and it is the same with Nollywood, which is hardly ever shot on any sound stage. The films are shot in the homes, offices and streets of Nigeria.

The birth of the Nollywood industry is often attributed to a man called Kenneth Nnebue. He was a video salesman, and he wanted to sell a consignment of blank tapes he had on his hands from Taiwan. He was having trouble selling them, so he thought he’d put something on them to help shift some stock. And that’s basically what he did. The first Nollywood films, in a sense, were kind of Yoruba street theater on video. You can see the seeds of Nollywood’s style here. Yoruba street theater is so much of the environment and it is the same with Nollywood, which is hardly ever shot on any sound stage. The films are shot in the homes, offices and streets of Nigeria.

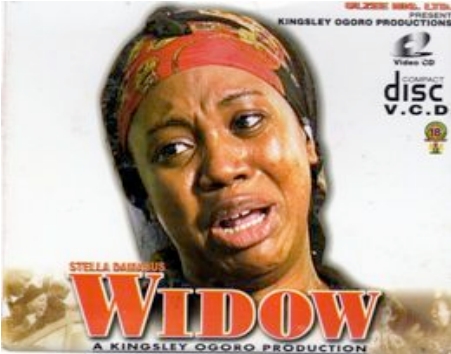

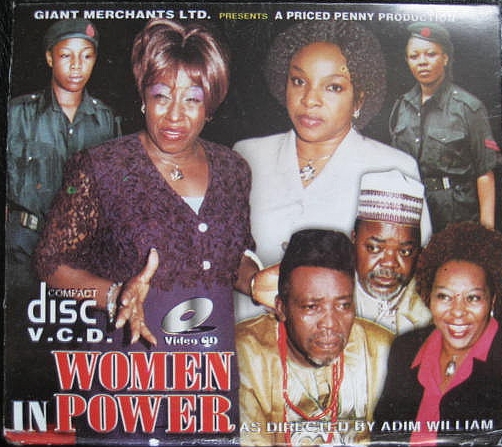

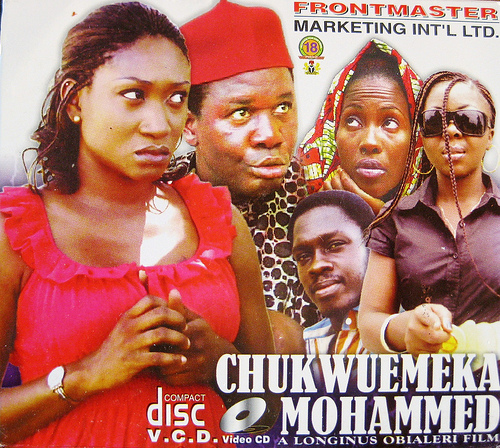

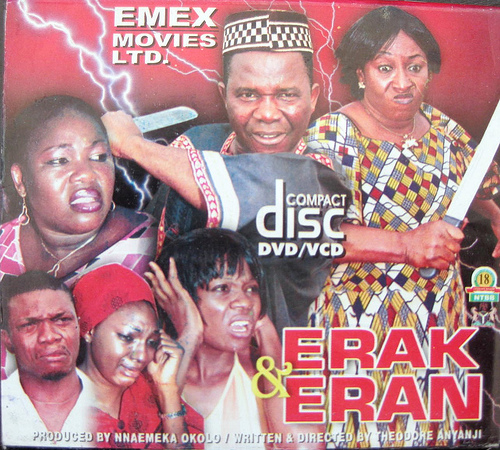

Nollywood is apparently now the second-largest film industry in the world, and in terms of the number of actual films that are put out it’s probably the most prolific. Nollywood is, in a sense, like soap opera on steroids. It’s what should have been on television, but was forced out into the open market to fend for itself, and it has mutated into this hybrid B-movie/soap operatic form where the films are often 3-4 hours long, hyperbolic, melodramatic but made for TV. They are highly uncinematic in visual scope. It’s an industry with many genres within it: you’ve got gangster movies; you’ve got what they call juju films, which feature voodoo and the supernatural in them; there’s something called the City Girl genre, which is all about young women in the city making their way in the world, and the kind of pitfalls that they come across; then there’s the Hallelujah movies which are often produced by churches themselves, and offer stories with crises that are resolved by the church. All the films are generic morality tales for the most part, and they can be quite politically incorrect. Oh, and they have the most fantastic titles.

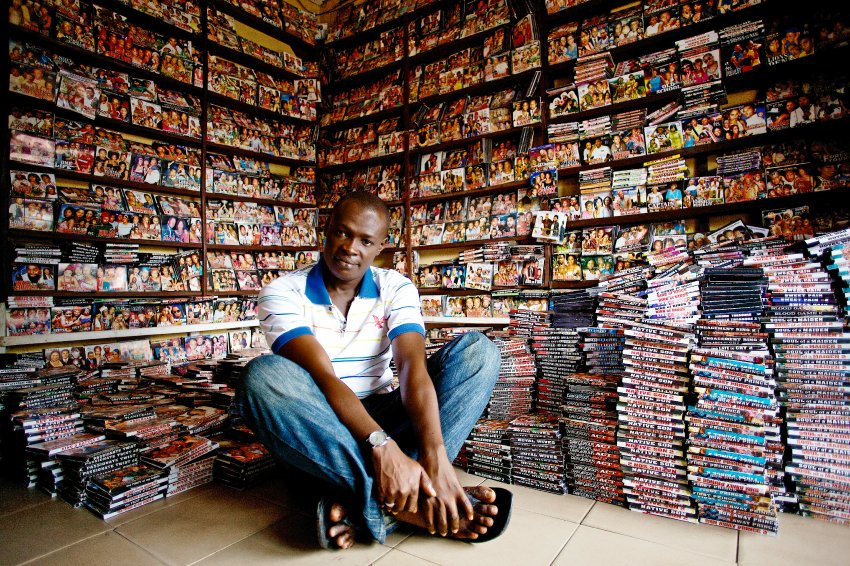

In the ’80s there, due to political and economic upheaval, security issues meant movie theaters were abandoned and re-purposed. Some of them became churches or warehouses, but they weren’t showing movies anymore. As a result of these security issues people just wanted to be able to enjoy entertainment at home, and that’s what Nollywood provided. And if you were too poor to have, say, a video player, certainly in the slums there’d be these little booths where people would pay a tiny, tiny amount of money, and they could go to these places within your little neighborhood, and you could watch Nollywood movies there. So, Nollywood is very much a straight-to-DVD or VCD industry.

In the ’80s there, due to political and economic upheaval, security issues meant movie theaters were abandoned and re-purposed. Some of them became churches or warehouses, but they weren’t showing movies anymore. As a result of these security issues people just wanted to be able to enjoy entertainment at home, and that’s what Nollywood provided. And if you were too poor to have, say, a video player, certainly in the slums there’d be these little booths where people would pay a tiny, tiny amount of money, and they could go to these places within your little neighborhood, and you could watch Nollywood movies there. So, Nollywood is very much a straight-to-DVD or VCD industry.

How did you become interested in Nollywood films, and how did you explore them through art?

I’ve been obsessed with Nollywood ever since, I think, the time of the millennium when I saw these posters in London, where I was living at the time. And I assumed these posters were advertising some sort of Caribbean plays, because I saw these women with these crazy wigs and long nails and they had the kind of dancehall feel to them. I found out about 5 or 6 years later that they were actually Nigerian movies. Also, whenever you go to an African hairdressers and have your hair braided, often Nollywood movies are shown in the corner of the room to entertain clients. Certainly here in New York, you have street hawkers coming around selling you the videos as you are having your hair done, so it was-and-is something that I couldn’t avoid. I became obsessed with the form of these films and the very idea and existence of the industry, because I realized what they were doing was something revolutionary. It’s the first time we’ve seen Africans representing ourselves in a visual medium on a mass scale. That hasn’t really happened before. I think other African film industries get a lot of involvement from the West, and money coming from the EU, or through France or what have you. And some of the films, especially the Francophone film industry, are beautiful films and extremely well-made, except often no one saw them. They’re called “embassy films,” because they’re the sort of films that get played in embassies or a film festival to a small elite group of people. But with Nollywood, all strata of society watch

I’ve been obsessed with Nollywood ever since, I think, the time of the millennium when I saw these posters in London, where I was living at the time. And I assumed these posters were advertising some sort of Caribbean plays, because I saw these women with these crazy wigs and long nails and they had the kind of dancehall feel to them. I found out about 5 or 6 years later that they were actually Nigerian movies. Also, whenever you go to an African hairdressers and have your hair braided, often Nollywood movies are shown in the corner of the room to entertain clients. Certainly here in New York, you have street hawkers coming around selling you the videos as you are having your hair done, so it was-and-is something that I couldn’t avoid. I became obsessed with the form of these films and the very idea and existence of the industry, because I realized what they were doing was something revolutionary. It’s the first time we’ve seen Africans representing ourselves in a visual medium on a mass scale. That hasn’t really happened before. I think other African film industries get a lot of involvement from the West, and money coming from the EU, or through France or what have you. And some of the films, especially the Francophone film industry, are beautiful films and extremely well-made, except often no one saw them. They’re called “embassy films,” because they’re the sort of films that get played in embassies or a film festival to a small elite group of people. But with Nollywood, all strata of society watch  these films, from the very educated, to the people who are illiterate. But it’s not only within Nigeria. It’s all over the continent and around the world. I mean, you can watch these films on YouTube. It is a huge industry that was beginning to get wider global attention and it just felt like it demanded unpacking. I also liked the idea of the industry because it was dealing with urban Africa. If you grow up in the West, the predominant image you have of Africa is that of rural poverty, which does exist, but it’s not the only story that’s going on. Africa is one of the fastest-urbanizing regions in the world, and actually what happens in the cities directly affects what happens in the countryside. So those outside Africa are only ever getting half the story. In the last 20 years Nollywood, whether it knows it or not, has been the only media industry that’s dealt with this idea of a rapidly urbanizing continent. They are navigating all the kind of issues that are arising from urbanization: the transition from traditional values to “city values” for example.

these films, from the very educated, to the people who are illiterate. But it’s not only within Nigeria. It’s all over the continent and around the world. I mean, you can watch these films on YouTube. It is a huge industry that was beginning to get wider global attention and it just felt like it demanded unpacking. I also liked the idea of the industry because it was dealing with urban Africa. If you grow up in the West, the predominant image you have of Africa is that of rural poverty, which does exist, but it’s not the only story that’s going on. Africa is one of the fastest-urbanizing regions in the world, and actually what happens in the cities directly affects what happens in the countryside. So those outside Africa are only ever getting half the story. In the last 20 years Nollywood, whether it knows it or not, has been the only media industry that’s dealt with this idea of a rapidly urbanizing continent. They are navigating all the kind of issues that are arising from urbanization: the transition from traditional values to “city values” for example.  Also, from a diaspora perspective, a lot of these films actually show you the real Nigeria. They’re shot in people’s actual homes and offices and on the street, so in a sense, you are truly watching Nigeria. I think, generally, people say that the films are shlocky and that they’re badly made, but I also find them quite magnetic. There are some really weird and exciting ticks and conventions that you find in Nollywood and I was not prepared to automatically dismiss them. No matter how educated or sophisticated you think you are, certain kinds of people find themselves very seduced by these films, and I am certainly one of those people. And I think I wanted to really unpack why I was so seduced by the them. So, this is what this art exhibition I did was about. I called it Sharon Stone in Abuja (after a Nollywood film of the same title) and invited four amazing artists — which included Wangechi Mutu, Mickaelene Thomas, Nigerian photographer Andrew Esiebo and the South African photographer Pieter Hugo (the first major international artist to deal with Nollywood) — to come

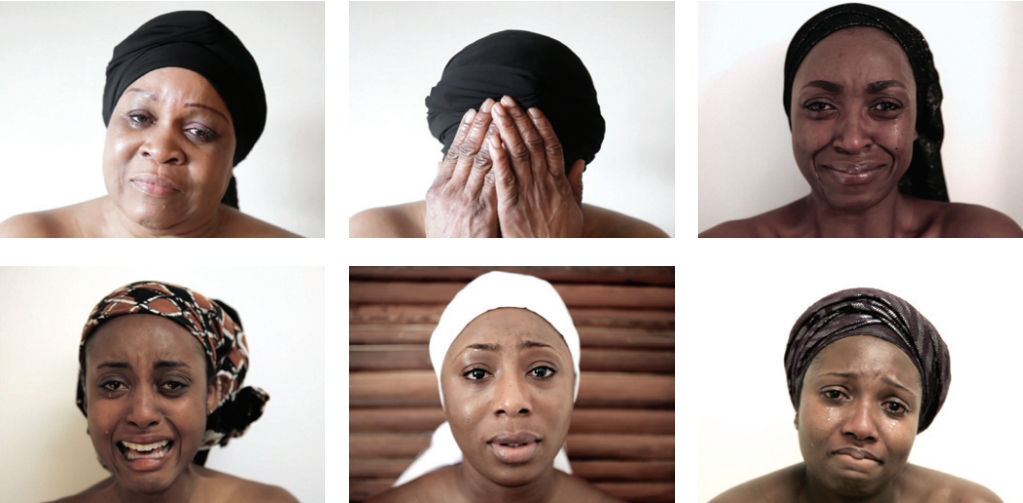

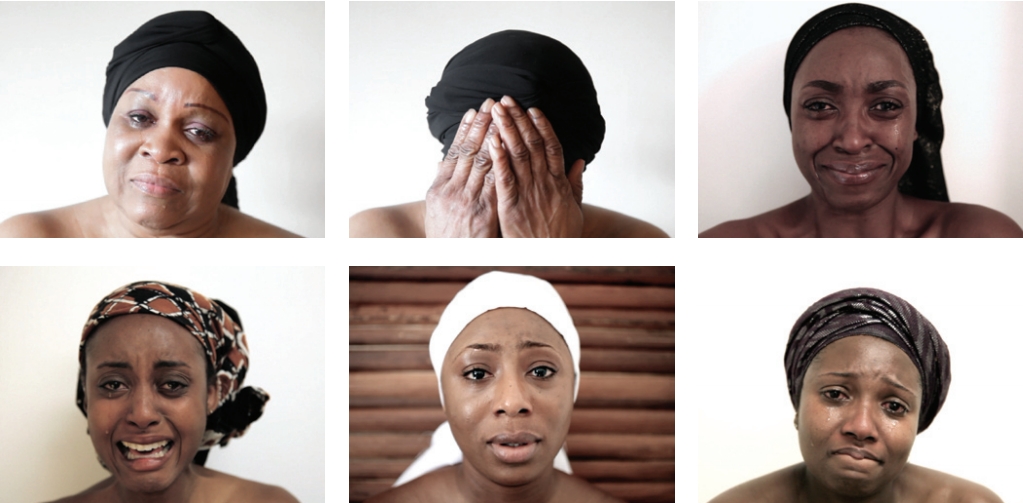

Also, from a diaspora perspective, a lot of these films actually show you the real Nigeria. They’re shot in people’s actual homes and offices and on the street, so in a sense, you are truly watching Nigeria. I think, generally, people say that the films are shlocky and that they’re badly made, but I also find them quite magnetic. There are some really weird and exciting ticks and conventions that you find in Nollywood and I was not prepared to automatically dismiss them. No matter how educated or sophisticated you think you are, certain kinds of people find themselves very seduced by these films, and I am certainly one of those people. And I think I wanted to really unpack why I was so seduced by the them. So, this is what this art exhibition I did was about. I called it Sharon Stone in Abuja (after a Nollywood film of the same title) and invited four amazing artists — which included Wangechi Mutu, Mickaelene Thomas, Nigerian photographer Andrew Esiebo and the South African photographer Pieter Hugo (the first major international artist to deal with Nollywood) — to come together to explore these ideas. As well as curating I made a couple of experimental Nollywood films and I also created a video installation called “Mourning Class” where I got these Nigerian actresses to cry-on-cue for the camera down the barrel of the lens. I also created an installation of a “Nollywood” living room with the fantastic Mickalene Thomas. Another thing I did was make a wallpaper which featured something like a thousand Nollywood film titles. When you read the titles, it discharges an emotional power somehow and you start to get a sense of what’s going on psychologically with Nigerians. You’ve got these crazy titles like Church Prostitute, God, Where Are You?, Broken Soul — all very dramatic, but also really funny and magnetic, which gives you a sense of the psychological landscape of Nigeria and Africa. And that’s really what I think I was most excited about, this opportunity to explore the emotional landscape of Africa, which is something you don’t hear about often. That is terrain that is little exposed, as our literary and media industries are nascent and suffer from lack of infrastructure and investment, so our stories are literally not out there in the world. But Nollywood has contributed a huge amount, in terms of numbers, to this dearth of story-telling. They are laying bare the African heart. Here I must demur: I find Nollywood films to be emotive but not truly emotional, and the “African heart” is a layered and complex thing, but Nollywood I hope is the beginning of an explosion of new stories from all over the continent and diaspora that explore this “African heart,” such as it is.

together to explore these ideas. As well as curating I made a couple of experimental Nollywood films and I also created a video installation called “Mourning Class” where I got these Nigerian actresses to cry-on-cue for the camera down the barrel of the lens. I also created an installation of a “Nollywood” living room with the fantastic Mickalene Thomas. Another thing I did was make a wallpaper which featured something like a thousand Nollywood film titles. When you read the titles, it discharges an emotional power somehow and you start to get a sense of what’s going on psychologically with Nigerians. You’ve got these crazy titles like Church Prostitute, God, Where Are You?, Broken Soul — all very dramatic, but also really funny and magnetic, which gives you a sense of the psychological landscape of Nigeria and Africa. And that’s really what I think I was most excited about, this opportunity to explore the emotional landscape of Africa, which is something you don’t hear about often. That is terrain that is little exposed, as our literary and media industries are nascent and suffer from lack of infrastructure and investment, so our stories are literally not out there in the world. But Nollywood has contributed a huge amount, in terms of numbers, to this dearth of story-telling. They are laying bare the African heart. Here I must demur: I find Nollywood films to be emotive but not truly emotional, and the “African heart” is a layered and complex thing, but Nollywood I hope is the beginning of an explosion of new stories from all over the continent and diaspora that explore this “African heart,” such as it is.

What issues are at play for Nollywood’s wig-wearing actresses — and in your own film, Phyllis?

I’m obsessed with the wig-wearing element in Nollywood films. There are all these women that wear kind of outrageous and outlandish wigs, and you really notice them in films like Beyonce & Rihanna. In the films, these two women called Bernice and Rhyme (not Beyonce and Rihanna at all) and they’re fighting over a guy called Jay. They battle for him partly in the home, but also at these singing competitions. I mean, it kind of has to be seen to be believed. And the actresses look so different in nearly every single scene. Their hairstyles change regularly. There is a little bit of a code I feel with all this wig-wearing. I think the badder the woman is, or the more evil she is, the more likely she’ll wear a terribly-colored wig and have long false nails. The more traditional-looking woman, who’s sweeter, obedient and much more long-suffering, is less likely to be in a colorful wig. She’ll have braids or cover her hair and wear traditional clothing. So, there is this idea of evil being represented with these wigs, and they’re kind of appalling to look at.

I’m obsessed with the wig-wearing element in Nollywood films. There are all these women that wear kind of outrageous and outlandish wigs, and you really notice them in films like Beyonce & Rihanna. In the films, these two women called Bernice and Rhyme (not Beyonce and Rihanna at all) and they’re fighting over a guy called Jay. They battle for him partly in the home, but also at these singing competitions. I mean, it kind of has to be seen to be believed. And the actresses look so different in nearly every single scene. Their hairstyles change regularly. There is a little bit of a code I feel with all this wig-wearing. I think the badder the woman is, or the more evil she is, the more likely she’ll wear a terribly-colored wig and have long false nails. The more traditional-looking woman, who’s sweeter, obedient and much more long-suffering, is less likely to be in a colorful wig. She’ll have braids or cover her hair and wear traditional clothing. So, there is this idea of evil being represented with these wigs, and they’re kind of appalling to look at. I’m kind of attracted to things that are appalling, and I knew I had to do something with that. I didn’t know what I was going to do, and I actually got to Nigeria without a finalized script. I had been trying to work on something, and had kept scrapping absolutely everything. I even talked to a couple of writers, and asked them to write me something, and again I scrapped everything because nothing seemed to work. But when I got to Nigeria, it was Nigeria that suddenly made this film happen. It was very odd. I remember listening to “What the World Needs Now Is Love” by Burt Bacharach, sung by Dionne Warwick. And I remember listening to the song for about two days non-stop almost meditatively. Now I love Burt Bacharach, but not normally that much! But it was through this song that Phyllis emerged. It’s almost like this was her favorite song. She gave me her name. She told me who she was. I know it sounds really strange, but it’s what happened.

I’m kind of attracted to things that are appalling, and I knew I had to do something with that. I didn’t know what I was going to do, and I actually got to Nigeria without a finalized script. I had been trying to work on something, and had kept scrapping absolutely everything. I even talked to a couple of writers, and asked them to write me something, and again I scrapped everything because nothing seemed to work. But when I got to Nigeria, it was Nigeria that suddenly made this film happen. It was very odd. I remember listening to “What the World Needs Now Is Love” by Burt Bacharach, sung by Dionne Warwick. And I remember listening to the song for about two days non-stop almost meditatively. Now I love Burt Bacharach, but not normally that much! But it was through this song that Phyllis emerged. It’s almost like this was her favorite song. She gave me her name. She told me who she was. I know it sounds really strange, but it’s what happened.  And then, obviously all the work I’d been doing and the thinking I’d been doing about the wigs sort of fell into place within this new story I had been “given.” I went wig-shopping and found all these different wigs, and then I felt like I wanted to find her home. And my production assistant took me to these one-star hotels in these slum areas in Lagos. As I was visiting all these one-star hotels, I knew I was looking for a blue room. And I only found one blue room, but it was the perfect blue room. Grimy, carpeted (and this in humid Nigeria) and quite desolate, but full of atmospheric potency. It was the blue room that I used, and I found a beautiful, beautiful actress/model called Sola, and so Phyllis was born. And I remember in Nigeria, there are all these Nollywood posters everywhere, plastic flowers and plastic trinkets all over the markets. And there’s just this syntheticness of Nollywood that I’m appalled by, but also attracted to. I want to represent that, so I invented this character through which I could express

And then, obviously all the work I’d been doing and the thinking I’d been doing about the wigs sort of fell into place within this new story I had been “given.” I went wig-shopping and found all these different wigs, and then I felt like I wanted to find her home. And my production assistant took me to these one-star hotels in these slum areas in Lagos. As I was visiting all these one-star hotels, I knew I was looking for a blue room. And I only found one blue room, but it was the perfect blue room. Grimy, carpeted (and this in humid Nigeria) and quite desolate, but full of atmospheric potency. It was the blue room that I used, and I found a beautiful, beautiful actress/model called Sola, and so Phyllis was born. And I remember in Nigeria, there are all these Nollywood posters everywhere, plastic flowers and plastic trinkets all over the markets. And there’s just this syntheticness of Nollywood that I’m appalled by, but also attracted to. I want to represent that, so I invented this character through which I could express my love and hate and fear and loathing of the syntheticness of Nigeria and this practice of wig-wearing. So, Phyllis, this character, is an obsessive. She’s mute and she lives in this one room. She’s obsessed with Nollywood and the emotions and passion she sees within these films, and she has Nollywood posters everywhere. She’s a Christian, and she has these plastic Jesus clocks all over her two rooms. She lives alone. She’s a single woman. And I think with Nollywood, women like that, they’re called “ashawo” — which literally means “wayward woman.” Women who are single are seen as a threat somehow. But ultimately, Phyllis represents the gap between our true essence and the plasticity — represented by plastic flowers, knick-knacks and furnishings, and the performative emotiveness that exists in Nigeria. Phyllis is trying to access what she perceives as humanity through the wigs, through synthetic representations of Jesus, and through Nollywood. They are short-term hits, and she is ultimately doomed to a cycle of longing and short-term satisfaction. But people read all sorts of things into Phyllis, and she means different things to different people. I am totally open to interpretation of what this film means. I’m not even sure I know what the film fully means. And I made it…

my love and hate and fear and loathing of the syntheticness of Nigeria and this practice of wig-wearing. So, Phyllis, this character, is an obsessive. She’s mute and she lives in this one room. She’s obsessed with Nollywood and the emotions and passion she sees within these films, and she has Nollywood posters everywhere. She’s a Christian, and she has these plastic Jesus clocks all over her two rooms. She lives alone. She’s a single woman. And I think with Nollywood, women like that, they’re called “ashawo” — which literally means “wayward woman.” Women who are single are seen as a threat somehow. But ultimately, Phyllis represents the gap between our true essence and the plasticity — represented by plastic flowers, knick-knacks and furnishings, and the performative emotiveness that exists in Nigeria. Phyllis is trying to access what she perceives as humanity through the wigs, through synthetic representations of Jesus, and through Nollywood. They are short-term hits, and she is ultimately doomed to a cycle of longing and short-term satisfaction. But people read all sorts of things into Phyllis, and she means different things to different people. I am totally open to interpretation of what this film means. I’m not even sure I know what the film fully means. And I made it…

Phyllis is essentially a vampire tale — how are vampires generally portrayed in Nollywood?

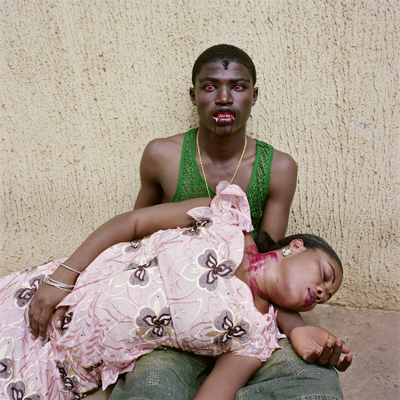

I feel that Nigerian vampires are still very much taken from an American idea of what vampires are about — blood-sucking, or soul-sucking in some way. And in Nollywood, representationally there is a very amateur-dramatics approach to the makeup. It’s certainly not on the level of True Blood or anything, but it still has a kind of traditional aesthetic about it which I find quite powerful. But I knew I wanted to do something much more psychological, and I’m obsessed with the idea of the psychic vampire, and believe these people exist. Anyone can be a psychic vampire — you can be, I can be. It’s literally just someone who sort of drains your energy, and that’s really what a psychic vampire is on some level. But I wanted to kick it up a notch

I feel that Nigerian vampires are still very much taken from an American idea of what vampires are about — blood-sucking, or soul-sucking in some way. And in Nollywood, representationally there is a very amateur-dramatics approach to the makeup. It’s certainly not on the level of True Blood or anything, but it still has a kind of traditional aesthetic about it which I find quite powerful. But I knew I wanted to do something much more psychological, and I’m obsessed with the idea of the psychic vampire, and believe these people exist. Anyone can be a psychic vampire — you can be, I can be. It’s literally just someone who sort of drains your energy, and that’s really what a psychic vampire is on some level. But I wanted to kick it up a notch  to someone who downloads your memories, thoughts and emotions — your essence. Also, Nollywood films aren’t particularly psychological. And so, I thought I wanted do something that was Sci-Fi, but also a little bit more psychological, emotional and tender at the same time. I knew I also wanted to do something a lot kinder to these outsider figures. I wanted to explore the vulnerabilities of the predator and outsider.

to someone who downloads your memories, thoughts and emotions — your essence. Also, Nollywood films aren’t particularly psychological. And so, I thought I wanted do something that was Sci-Fi, but also a little bit more psychological, emotional and tender at the same time. I knew I also wanted to do something a lot kinder to these outsider figures. I wanted to explore the vulnerabilities of the predator and outsider.

Where do beliefs in supernatural things like witchcraft fit into Nollywood and Nigerian culture?

I would say that the supernatural is still something that’s quite important in Nollywood and parts of Nigeria. There is a belief in it (Though I have been thinking recently about what belief means in an African context. I often think that the mode and function and expression of belief is quite different from what it is in the West, but that’s another conversation!). So people don’t want to necessarily admit it, but there is a belief in it, and it sort of seeps into the way that Christianity is expressed as well. When I look at Christianity in Africa, it doesn’t always look so Christian to me. I think there’s something that feels very animistic about it. The idea of transformation and magic seems much more amplified and intense within African Christianity, and I kind of really wanted to explore that. In Nollywood films as well, even when you least expect it, somehow they’ll change genre. You’ll watch what you think is a romantic film, and then suddenly there will be this supernatural element that will appear an hour-and-a-half into it, that hasn’t hitherto announced itself. This is always a force that’s there. I think that also in a country where there’s so much endemic chaos, where people are just fighting for survival, watching a film that invokes the supernatural provides relief and a satisfying

I would say that the supernatural is still something that’s quite important in Nollywood and parts of Nigeria. There is a belief in it (Though I have been thinking recently about what belief means in an African context. I often think that the mode and function and expression of belief is quite different from what it is in the West, but that’s another conversation!). So people don’t want to necessarily admit it, but there is a belief in it, and it sort of seeps into the way that Christianity is expressed as well. When I look at Christianity in Africa, it doesn’t always look so Christian to me. I think there’s something that feels very animistic about it. The idea of transformation and magic seems much more amplified and intense within African Christianity, and I kind of really wanted to explore that. In Nollywood films as well, even when you least expect it, somehow they’ll change genre. You’ll watch what you think is a romantic film, and then suddenly there will be this supernatural element that will appear an hour-and-a-half into it, that hasn’t hitherto announced itself. This is always a force that’s there. I think that also in a country where there’s so much endemic chaos, where people are just fighting for survival, watching a film that invokes the supernatural provides relief and a satisfying  answer to why it took me 5 hours to make what should have been a 30-minute journey, or why is that dead body still lying in the road from that accident days ago. All these kinds of calamities that seem to happen on a daily basis that people have to absorb emotionally need a release, and these films are a relief mechanism. I think they give a lot of emotionally satisfying explanations. I don’t know if it’s necessarily cognitive. Maybe for some people, but I wouldn’t say that was the case for all. So within this chaos this idea of spirit possession and exorcism is hugely important. Deliverance is another experimental Nollywood film I made. The film starts out with this priest, who you can’t see, talking about how you recognize a witch. His script, I actually adapted it from a UNESCO report where they interviewed priests — not actually in Nigeria, but in the Congo — and these priests are talking about how you recognize a child witch. And all of these things they’re describing — “they’re disobedient, they’re

answer to why it took me 5 hours to make what should have been a 30-minute journey, or why is that dead body still lying in the road from that accident days ago. All these kinds of calamities that seem to happen on a daily basis that people have to absorb emotionally need a release, and these films are a relief mechanism. I think they give a lot of emotionally satisfying explanations. I don’t know if it’s necessarily cognitive. Maybe for some people, but I wouldn’t say that was the case for all. So within this chaos this idea of spirit possession and exorcism is hugely important. Deliverance is another experimental Nollywood film I made. The film starts out with this priest, who you can’t see, talking about how you recognize a witch. His script, I actually adapted it from a UNESCO report where they interviewed priests — not actually in Nigeria, but in the Congo — and these priests are talking about how you recognize a child witch. And all of these things they’re describing — “they’re disobedient, they’re  too clever, they’re too kind” — lots of contradictions, and a really, really strange list of attributes that are just basically very human or literally describing what it is to be a child. What happens to this girl is she sort of defies this voiceover by becoming a visual representation of a child witch. I literally dressed her in a Halloween witch’s outfit, which also highlighted the difference between the way “child witches” are seen in the West, and how “child witches” are seen in Africa, which is as something threatening. Anyway, so this little girl (called Comfort) goes trick-or-treating and she knocks on the door of a priest’s house, and the priests come out and they bang a nail into her head, which is one of the many terrible things that some of these so-called priests do to child witches. The priests begin to pray over the child,

too clever, they’re too kind” — lots of contradictions, and a really, really strange list of attributes that are just basically very human or literally describing what it is to be a child. What happens to this girl is she sort of defies this voiceover by becoming a visual representation of a child witch. I literally dressed her in a Halloween witch’s outfit, which also highlighted the difference between the way “child witches” are seen in the West, and how “child witches” are seen in Africa, which is as something threatening. Anyway, so this little girl (called Comfort) goes trick-or-treating and she knocks on the door of a priest’s house, and the priests come out and they bang a nail into her head, which is one of the many terrible things that some of these so-called priests do to child witches. The priests begin to pray over the child,  and try to ‘exorcise’ the “devil within” her, and they’re sort of focusing on this idea of the devil so much that the devil appears. I feel that when you focus on the idea so much of what you hate, you’re giving it life, because for me that is what the power of belief is about. If you’re focusing on it, and if you believe in it so much because you’re so scared of it, then you make it real. Actually, by the end of the film, you realize that the priests and the so-called devil need each other. But also, the idea of the devil allows me to explore the relationship between pagan religion and Christianity, because the devil is actually an Exu figure. Exu is kind of a Yoruba, Nigerian, pre-Christian messenger deity, I suppose. I think the

and try to ‘exorcise’ the “devil within” her, and they’re sort of focusing on this idea of the devil so much that the devil appears. I feel that when you focus on the idea so much of what you hate, you’re giving it life, because for me that is what the power of belief is about. If you’re focusing on it, and if you believe in it so much because you’re so scared of it, then you make it real. Actually, by the end of the film, you realize that the priests and the so-called devil need each other. But also, the idea of the devil allows me to explore the relationship between pagan religion and Christianity, because the devil is actually an Exu figure. Exu is kind of a Yoruba, Nigerian, pre-Christian messenger deity, I suppose. I think the  Christian missionaries came along and decided to call the Exu figure a devil, but the Exu isn’t a devil. The Exu is a trickster that plays tricks on mankind, that mankind might learn something about himself. So actually the pre-Christian Yoruba idea of “evil” is so much more sophisticated. Anyway, this Exu motif was my way of highlighting what I feel to be the similarities that might exist between traditional African animistic belief and modern-day African Christianity practice.

Christian missionaries came along and decided to call the Exu figure a devil, but the Exu isn’t a devil. The Exu is a trickster that plays tricks on mankind, that mankind might learn something about himself. So actually the pre-Christian Yoruba idea of “evil” is so much more sophisticated. Anyway, this Exu motif was my way of highlighting what I feel to be the similarities that might exist between traditional African animistic belief and modern-day African Christianity practice.

Since this is Nigeria, are Islamic themes as prevalent in Nollywood films as Christian themes?

There is a Hausa film industry — that’s the film industry in the north of Nigeria — and they get their cue more from Bollywood actually. And so there’s more sort of singing and dancing, and it’s folkloric. I’d say it’s a lot less racy than Nollywood, but Nollywood is hardly that sexual either. You know, there are certain things that aren’t allowed. But I would say the northern film industry is far less than that too, even though there are people that complain, but I think their value systems are very different. I don’t think they’re as international, because they don’t do English-language films. That’s the only reason that I haven’t necessarily seen that many of them, because few of them are in the English language. Of course, there are Muslims in the south as well. And Yoruba people who are from the southwest of the country, many of them are Muslims too. But somehow, no, it feels as if the Nollywood that’s exported to the rest of the world doesn’t seem to contain so much to do with Islam within it. But I still feel that there’s the element of spirituality, which is universal throughout all of Nigeria. I feel that definitely in all the films.

There is a Hausa film industry — that’s the film industry in the north of Nigeria — and they get their cue more from Bollywood actually. And so there’s more sort of singing and dancing, and it’s folkloric. I’d say it’s a lot less racy than Nollywood, but Nollywood is hardly that sexual either. You know, there are certain things that aren’t allowed. But I would say the northern film industry is far less than that too, even though there are people that complain, but I think their value systems are very different. I don’t think they’re as international, because they don’t do English-language films. That’s the only reason that I haven’t necessarily seen that many of them, because few of them are in the English language. Of course, there are Muslims in the south as well. And Yoruba people who are from the southwest of the country, many of them are Muslims too. But somehow, no, it feels as if the Nollywood that’s exported to the rest of the world doesn’t seem to contain so much to do with Islam within it. But I still feel that there’s the element of spirituality, which is universal throughout all of Nigeria. I feel that definitely in all the films.

Did you cover a lot of African topics during your time working for BBC2’s, The Culture Show?

Not at all. And at the time, I was kind of interested in not necessarily being stereotyped, so I was always like, “Just because I’m African and Black, doesn’t mean I have to do African and Black issues.” And I was really fortunate. I was never ever stereotyped, and I always did whatever I wanted. That doesn’t happen to everyone, but somehow I managed to transcend that, and I was just like any other reporter or producer or researcher. And I just kind of did anything. But then it got to the point where I suddenly didn’t feel very powerful. I felt very weak somehow. And I knew that you could exist within that space, and you’re making a

Not at all. And at the time, I was kind of interested in not necessarily being stereotyped, so I was always like, “Just because I’m African and Black, doesn’t mean I have to do African and Black issues.” And I was really fortunate. I was never ever stereotyped, and I always did whatever I wanted. That doesn’t happen to everyone, but somehow I managed to transcend that, and I was just like any other reporter or producer or researcher. And I just kind of did anything. But then it got to the point where I suddenly didn’t feel very powerful. I felt very weak somehow. And I knew that you could exist within that space, and you’re making a  particular point in the sense that, yeah, a Black person and an African can talk about absolutely anything on the face of the planet, which I think was an important thing at the time. But then, for me, Africa started to feel so much more interesting. There’s just so much going on that’s undiscovered. It’s just so exciting, and also I felt it was important to combat the stories that were being told about my continent. It was very unbalanced, living in the UK. And I was not being told about an Africa that I necessarily recognized. I feel as if this is my destined path somehow, and I think I’ll always be interested in doing things about Africa and Africanness, but I also think that it might lead me somewhere else completely that might not have anything to do with anything African. But for now, it’s absolutely my focus and intent.

particular point in the sense that, yeah, a Black person and an African can talk about absolutely anything on the face of the planet, which I think was an important thing at the time. But then, for me, Africa started to feel so much more interesting. There’s just so much going on that’s undiscovered. It’s just so exciting, and also I felt it was important to combat the stories that were being told about my continent. It was very unbalanced, living in the UK. And I was not being told about an Africa that I necessarily recognized. I feel as if this is my destined path somehow, and I think I’ll always be interested in doing things about Africa and Africanness, but I also think that it might lead me somewhere else completely that might not have anything to do with anything African. But for now, it’s absolutely my focus and intent.

What was your father’s experience like producing Nigerian television during the 1980’s?

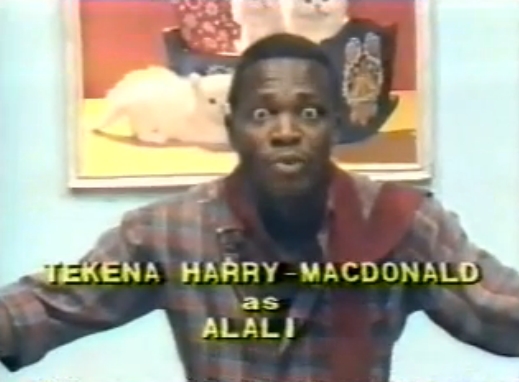

He had the TV program called Basi and Company, which was the most-watched TV program in Nigeria, and I think parts of Africa as well. Basi and Company was about a kind of Lagos hustler and his sidekick, Alali, and they lived in this one-room apartment, and his catchphrase was “to be a millionaire, think like a millionaire.” It was a satire on this Nigerian get-rich-quick mentality, pretty much, and there were all these other characters as well — the wealthy landlady, Madam the Madam; the barman; and then Segi, this beautiful slightly-devious woman. But this program was very successful, and we went to a taping once in Lagos, and there were studios then, so it wasn’t done in people’s homes. It was an actual studio setup, which is kind of interesting and kind of rare. I realized that when I was looking

He had the TV program called Basi and Company, which was the most-watched TV program in Nigeria, and I think parts of Africa as well. Basi and Company was about a kind of Lagos hustler and his sidekick, Alali, and they lived in this one-room apartment, and his catchphrase was “to be a millionaire, think like a millionaire.” It was a satire on this Nigerian get-rich-quick mentality, pretty much, and there were all these other characters as well — the wealthy landlady, Madam the Madam; the barman; and then Segi, this beautiful slightly-devious woman. But this program was very successful, and we went to a taping once in Lagos, and there were studios then, so it wasn’t done in people’s homes. It was an actual studio setup, which is kind of interesting and kind of rare. I realized that when I was looking  for this blue room [for Phyllis], I was probably thinking about Basi and Company for my finished film. Because the sets are very kind of rudimentary, and they’re just kind of terrible looking, and I kind of really liked that. There’s something really depressing but resonant about it. And I think I was looking for a blue-green room because of Basi and Company, and all those sets that had these blue-green walls. But it was a hugely successful TV show, and it was this idea of millions of Nigerians, or a billion Africans, laughing at themselves.

for this blue room [for Phyllis], I was probably thinking about Basi and Company for my finished film. Because the sets are very kind of rudimentary, and they’re just kind of terrible looking, and I kind of really liked that. There’s something really depressing but resonant about it. And I think I was looking for a blue-green room because of Basi and Company, and all those sets that had these blue-green walls. But it was a hugely successful TV show, and it was this idea of millions of Nigerians, or a billion Africans, laughing at themselves.

Had he lived, do you think he’d have used more-serious TV programs to advocate against Shell?

My father used a variety media to bring awareness to the struggle: he made a TV documentary; he had a political column and he wrote poetry. His political columns certainly got him into trouble all his life. But he moved much more towards speaking to environmental groups, appealing to international bodies and giving speeches on the ground in Nigeria. I suppose he was driven to that. But he never stopped writing. Having said that, I think if he was still alive, if he had gone into exile and if he hadn’t been killed — which would never have happened, because he was never one to run away from anything politically — I feel as if maybe he would have seen the long-term power of less polemic art. I feel as if he was probably trying to work out those issues actually, but his life was ended prematurely, and so I don’t know what he would have done. But I would have loved for him to have become someone who used his considerable artistic skills to create things that would have changed the culture on the ground

My father used a variety media to bring awareness to the struggle: he made a TV documentary; he had a political column and he wrote poetry. His political columns certainly got him into trouble all his life. But he moved much more towards speaking to environmental groups, appealing to international bodies and giving speeches on the ground in Nigeria. I suppose he was driven to that. But he never stopped writing. Having said that, I think if he was still alive, if he had gone into exile and if he hadn’t been killed — which would never have happened, because he was never one to run away from anything politically — I feel as if maybe he would have seen the long-term power of less polemic art. I feel as if he was probably trying to work out those issues actually, but his life was ended prematurely, and so I don’t know what he would have done. But I would have loved for him to have become someone who used his considerable artistic skills to create things that would have changed the culture on the ground through more novels and plays and films maybe. I do feel as if with these cultural solutions to social problems, it can be a much slower, longer haul. Building cultural capital and seeing the benefits of self-discovery and self-respect through having a vibrant and healthy artistic sector takes time, dedication, infrastructure, education. All the things my father was arguing the Ogoni people had at least the right to. I don’t think he felt he had the time to spare to wait for art to do it’s work. People were dying and this disrespect of Ogoni land and people had been going on for over 50 years.

through more novels and plays and films maybe. I do feel as if with these cultural solutions to social problems, it can be a much slower, longer haul. Building cultural capital and seeing the benefits of self-discovery and self-respect through having a vibrant and healthy artistic sector takes time, dedication, infrastructure, education. All the things my father was arguing the Ogoni people had at least the right to. I don’t think he felt he had the time to spare to wait for art to do it’s work. People were dying and this disrespect of Ogoni land and people had been going on for over 50 years.

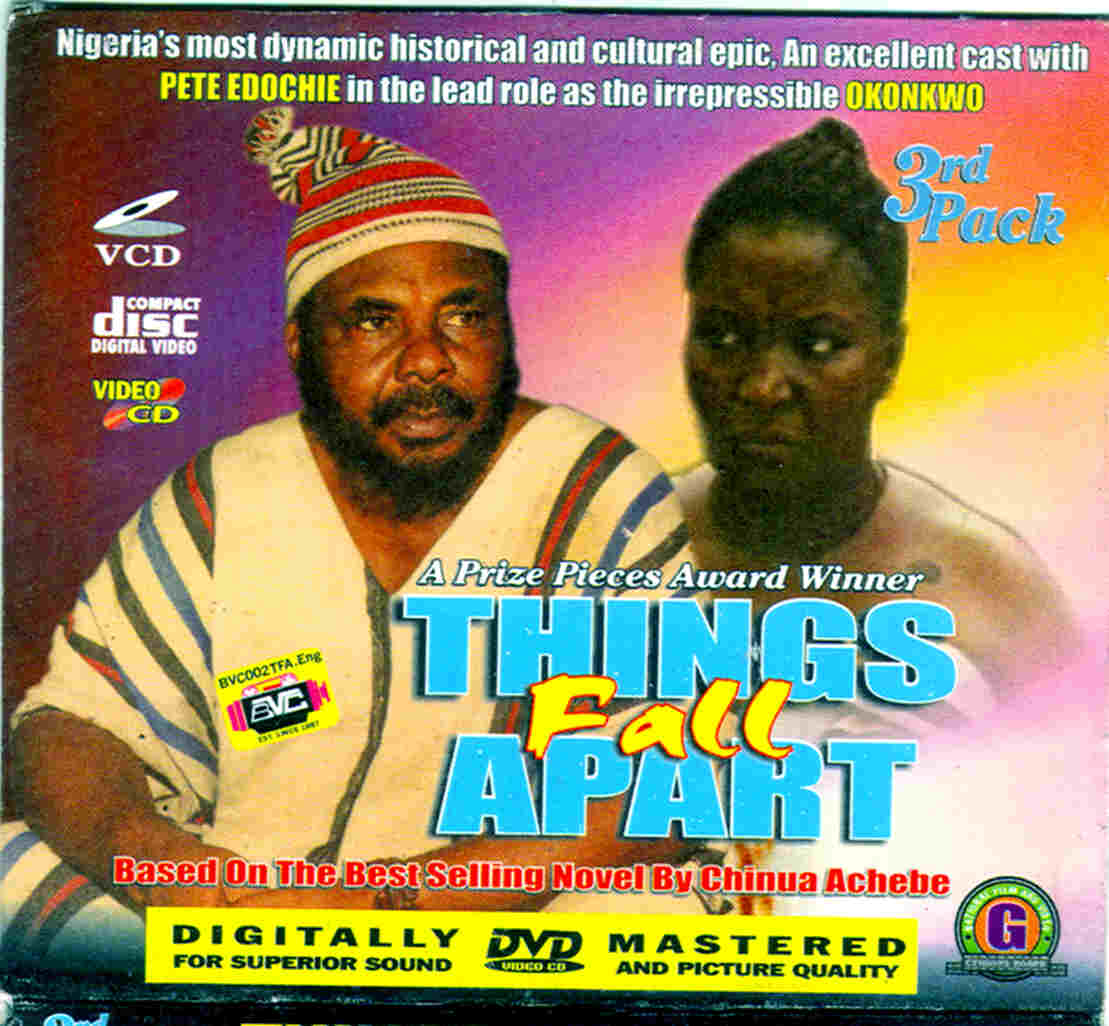

Do great Nigerian novels, like Things Fall Apart by Chinua Achebe, find their way into Nollywood?

There was a TV version of Things Fall Apart, but that was in the ’80’s I think with Pete Edochie — he’s a huge Nollywood actor now — but I would say no, there isn’t that relationship, and I think that serves as a huge problem. A lot of literary people kind of despair at Nollywood because of this. A lot of scripts are improvised anyway in Nollywood, so they have the basic outlines, and you’re shooting on the street, and you’re shooting at home, and you’re dealing with an environment that’s very chaotic. You know, you run out of time, you’re making scripts on the spot, and so there’s a lot of improvisation which actually gives the Nollywood films a kind of terrifying and terrible energy, and you’re sort of watching it like you’re watching an argument on the street and thinking, “What’s gonna happen next?” Some of it is pretty awful, some of the way people talk,

There was a TV version of Things Fall Apart, but that was in the ’80’s I think with Pete Edochie — he’s a huge Nollywood actor now — but I would say no, there isn’t that relationship, and I think that serves as a huge problem. A lot of literary people kind of despair at Nollywood because of this. A lot of scripts are improvised anyway in Nollywood, so they have the basic outlines, and you’re shooting on the street, and you’re shooting at home, and you’re dealing with an environment that’s very chaotic. You know, you run out of time, you’re making scripts on the spot, and so there’s a lot of improvisation which actually gives the Nollywood films a kind of terrifying and terrible energy, and you’re sort of watching it like you’re watching an argument on the street and thinking, “What’s gonna happen next?” Some of it is pretty awful, some of the way people talk,  and what they say. But sometimes it can be absolutely amazing — especially when you have these old Yoruba aphorisms that get expressed one way or another. Then also, there’s this idea that a lot of the marketeers are illiterate, and they’re also much more focused on making money, and so they’re not necessarily that sensitive to filmmakers that want to make a different kind of film. So, that’s an issue as well. Literary writers, I would say on the whole in Nigeria, do not like Nollywood. And I’m from a family of writers. I’m a writer myself, but I have such an individual interest. I knew I wanted to translate my interest in Nollywood into something else. And I actually made two silent movies, pretty much — Phyllis is certainly a silent movie — because I also wanted challenge this idea that Nollywood films have to be voluble. And sometimes there is so much noise, so much rubbish being talked, that I just think, “Can we just do something that’s silent?” and

and what they say. But sometimes it can be absolutely amazing — especially when you have these old Yoruba aphorisms that get expressed one way or another. Then also, there’s this idea that a lot of the marketeers are illiterate, and they’re also much more focused on making money, and so they’re not necessarily that sensitive to filmmakers that want to make a different kind of film. So, that’s an issue as well. Literary writers, I would say on the whole in Nigeria, do not like Nollywood. And I’m from a family of writers. I’m a writer myself, but I have such an individual interest. I knew I wanted to translate my interest in Nollywood into something else. And I actually made two silent movies, pretty much — Phyllis is certainly a silent movie — because I also wanted challenge this idea that Nollywood films have to be voluble. And sometimes there is so much noise, so much rubbish being talked, that I just think, “Can we just do something that’s silent?” and  “Let’s see if we can express Nigeria-ness through silence somehow.”

“Let’s see if we can express Nigeria-ness through silence somehow.”

There’s a lot of work that needs to be done in improving storytelling on film. I’ve made films on very, very little — much less than a Nollywood film would cost. But I think that you can try and drive at something else. And I would love to see that, something a bit edgier, and that’s precisely why I’m excited by the kinds of visual conventions and the way it looks — the aesthetics of Nollywood. I think there’s something really powerful in that. If only we’d go sideways, a little more left-field. I mean, Nollywood films, they are edgy in themselves — someone memorably described the genre as “abnormative” — and I think there is something very powerful within that. But I would also like to see them get away from sort of conservative ideas somehow, and do something that’s completely unexpected. If Nollywood did that, I feel as if you can spend $10,000, $15,000 on a film — especially if you make them shorter – and if you just decided to do something that was quite quirky, then I just think we’d have the most amazing genre on our hands that does something completely unique. That would be my dream, and I think my two short films, they’re both quick experiments  that use Nollywood to subvert Nollywood — what I call “alt-Nollywood.” It’s Nollywood eating itself. So, for me, I’m not going to throw away the wig idea. Let’s use the wig idea, it’s interesting, but let’s use it differently. Let’s use the really crap special effects that we have. Use it, work with it and do something with that. In The Deliverance of Comfort I used very rudimentary special effects, but that doesn’t mean you can’t layer it or imbue it with fresh ideas. Nigerians are literary, exciting, and deep. I think we are capable of producing something edgy and fresh, but I’m not quite sure why it isn’t happening. But if people dug a bit deeper, I think they could come up with something extraordinary.

that use Nollywood to subvert Nollywood — what I call “alt-Nollywood.” It’s Nollywood eating itself. So, for me, I’m not going to throw away the wig idea. Let’s use the wig idea, it’s interesting, but let’s use it differently. Let’s use the really crap special effects that we have. Use it, work with it and do something with that. In The Deliverance of Comfort I used very rudimentary special effects, but that doesn’t mean you can’t layer it or imbue it with fresh ideas. Nigerians are literary, exciting, and deep. I think we are capable of producing something edgy and fresh, but I’m not quite sure why it isn’t happening. But if people dug a bit deeper, I think they could come up with something extraordinary.