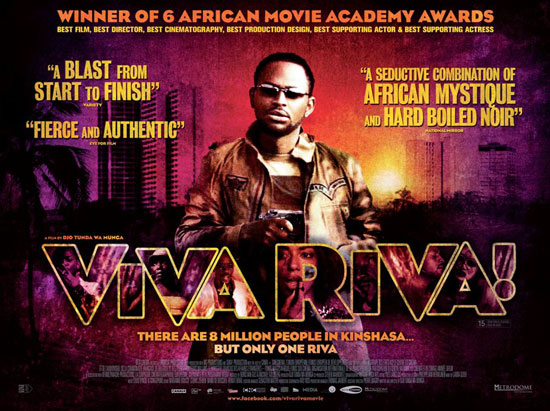

Who: Djo Tunda Wa Munga is a Congo-born filmmaker and the writer/director of the Kinshasa-set film, Viva Riva!. The film, which is the first Congolese feature since La Vie Est Belle almost 25 years ago, opens in New York and L.A. on June 10th. Music Box Films agreed to release Viva Riva! in the U.S. after it premiered at the Toronto Film Festival, but the film has had a more difficult time reaching Congolese audiences, since the country has no theater system. Despite this, Viva Riva! recently took home six awards, including best film, at the 7th Annual African Movie Academy Awards in Nigeria. It also won the inaugural Best African Movie prize at the 2011 MTV Movie Awards. The film centers on a small-time Congolese gangster, Riva, played by first-time actor Patsha Bay Mukuna. After bringing a truck-load of stolen gasoline home to Kinshasa, Riva is doggedly pursued by the leader of his old Angolan gang,

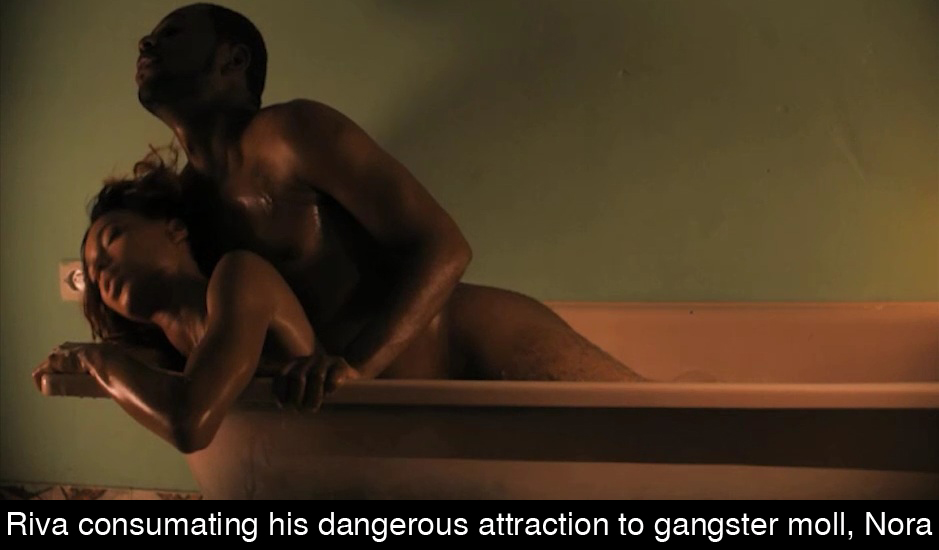

Who: Djo Tunda Wa Munga is a Congo-born filmmaker and the writer/director of the Kinshasa-set film, Viva Riva!. The film, which is the first Congolese feature since La Vie Est Belle almost 25 years ago, opens in New York and L.A. on June 10th. Music Box Films agreed to release Viva Riva! in the U.S. after it premiered at the Toronto Film Festival, but the film has had a more difficult time reaching Congolese audiences, since the country has no theater system. Despite this, Viva Riva! recently took home six awards, including best film, at the 7th Annual African Movie Academy Awards in Nigeria. It also won the inaugural Best African Movie prize at the 2011 MTV Movie Awards. The film centers on a small-time Congolese gangster, Riva, played by first-time actor Patsha Bay Mukuna. After bringing a truck-load of stolen gasoline home to Kinshasa, Riva is doggedly pursued by the leader of his old Angolan gang,  Cesar (Hoji Fortuna), while pursuing the affections of a gangster’s moll, Nora (Manie Malone). Munga grew up in Congo, but moved to Europe when he was 9 years old, only to return after finishing film school in Belgium to found Suka! Productions. Along with his South Africa-based producing partner, Steven Markovitz, Munga has made the documentaries Congo in Four Acts and State of Mind, and based his portrayal of Kinshasa in Viva Riva! on incidents from the Congolese capital city’s recent history.

Cesar (Hoji Fortuna), while pursuing the affections of a gangster’s moll, Nora (Manie Malone). Munga grew up in Congo, but moved to Europe when he was 9 years old, only to return after finishing film school in Belgium to found Suka! Productions. Along with his South Africa-based producing partner, Steven Markovitz, Munga has made the documentaries Congo in Four Acts and State of Mind, and based his portrayal of Kinshasa in Viva Riva! on incidents from the Congolese capital city’s recent history.

[Publisher’s Note: Special thanks to the staff at Sophie Gluck PR]

Was the gas shortage plot of Viva Riva! inspired by a real period in Kinshasa’s history?

That crisis did happen in 1999, 2000, 2001. You know, I took it from reality. And it was, I would say, in terms of numbers that I put in the film, these were real numbers. When I used to go and try to get some gas myself, you were paying these types of prices, and so that was real. But I just used that context, which was really interesting to talk about the society, to talk about the family, to talk about the relation to money, to talk about the environment of Riva. But that was real. That was factual.

That crisis did happen in 1999, 2000, 2001. You know, I took it from reality. And it was, I would say, in terms of numbers that I put in the film, these were real numbers. When I used to go and try to get some gas myself, you were paying these types of prices, and so that was real. But I just used that context, which was really interesting to talk about the society, to talk about the family, to talk about the relation to money, to talk about the environment of Riva. But that was real. That was factual.

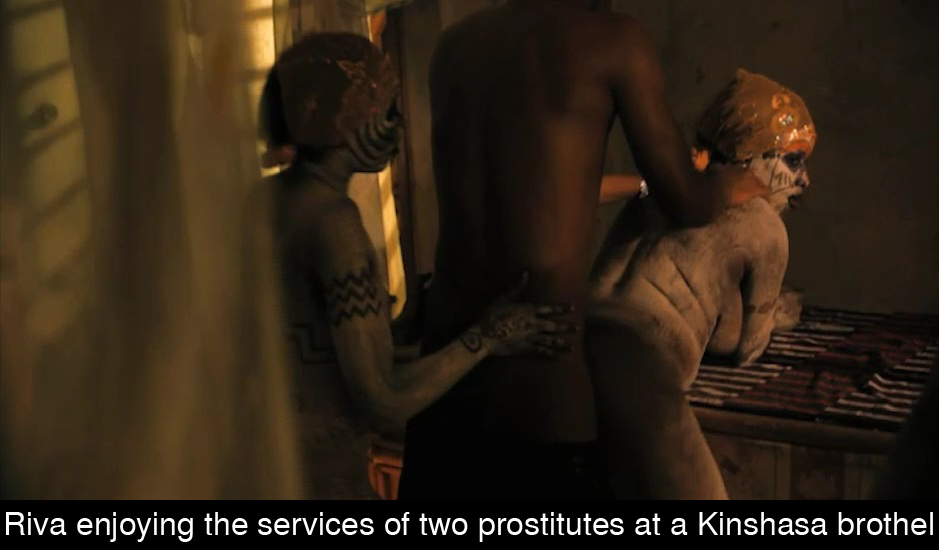

I wanted portray the last maybe 20 years of the city. Not to have an accurate portrayal, but to have a sense of giving a few important things that are part of the city. Nightlife, that you can have, but also the collapse of the family, which is also due to poverty, misery and all that happened in Kinshasa —  including the violence that came with the war. I represent that as a metaphor, but also the things like prostitution or eroticism, because Congo’s culture is quite conservative in ways. We know there is a high level of prostitution. When you walk in Kinshasa at 8 o’clock at night, 10 o’clock, you see a lot of women downtown. That is there, but as a culture we don’t accept that things have changed. There are all these taboos about talking about the relation between men and women, and this kind of eroticism. When you make a film like Viva Riva!, which as a country like mine has not produced a film in the last 25 years — I mean, this is a Congolese production. Before that, was a Belgian production. We

including the violence that came with the war. I represent that as a metaphor, but also the things like prostitution or eroticism, because Congo’s culture is quite conservative in ways. We know there is a high level of prostitution. When you walk in Kinshasa at 8 o’clock at night, 10 o’clock, you see a lot of women downtown. That is there, but as a culture we don’t accept that things have changed. There are all these taboos about talking about the relation between men and women, and this kind of eroticism. When you make a film like Viva Riva!, which as a country like mine has not produced a film in the last 25 years — I mean, this is a Congolese production. Before that, was a Belgian production. We  can consider this like a first Congolese production. I think there is a commitment to be as honest as possible to what you’ve experienced. That’s what I tried to do, and of course it was kind of a risk to have people say, “Why do you talk about these things?” Because this is us. The journey to maturity is also to accept who we are, and also to have control of our image — even if it’s not as soft and Hollywood-style. But do we really need that? I don’t think so.

can consider this like a first Congolese production. I think there is a commitment to be as honest as possible to what you’ve experienced. That’s what I tried to do, and of course it was kind of a risk to have people say, “Why do you talk about these things?” Because this is us. The journey to maturity is also to accept who we are, and also to have control of our image — even if it’s not as soft and Hollywood-style. But do we really need that? I don’t think so.

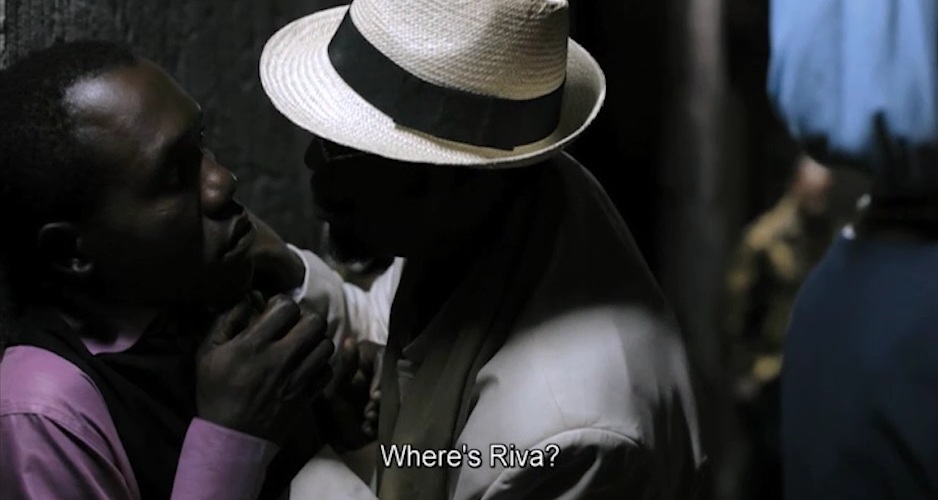

Talk about the tension between the Angolan gangsters and the Congolese they cross paths with.

Well, in my film I wanted to portray racism in Africa. That was my goal, because especially when you’re in Kinshasa, you see all these U.N. missions. You see all these African soldiers or African civilians who work there. I was quite shocked about how an African looks down on all the other African countries.  All these racisms are there, and we don’t often talk about it, so it was an opportunity to talk about this problem. The story is linked to Angola because Riva comes from Angola, he smuggles the money, and the foreigners are Angolan, so I put it on them. But at the time I wrote the story, it was like six, seven years ago. Things were fine between Angola and Congo. And after that, the last three years I think, the relations between the two countries has deteriorated in a way that I can’t even explain. But it was not meant to be that way. My purpose was not to say, “These are the Angolans. This is what they do to us.” No, it was not that.

All these racisms are there, and we don’t often talk about it, so it was an opportunity to talk about this problem. The story is linked to Angola because Riva comes from Angola, he smuggles the money, and the foreigners are Angolan, so I put it on them. But at the time I wrote the story, it was like six, seven years ago. Things were fine between Angola and Congo. And after that, the last three years I think, the relations between the two countries has deteriorated in a way that I can’t even explain. But it was not meant to be that way. My purpose was not to say, “These are the Angolans. This is what they do to us.” No, it was not that.

How important was casting Congolese actors to get their accents right?

If you want to play a real guy from Kinshasa, you need to bring some kind of perfume, otherwise the Congolese will say, “Oh Djo, you’re cheating here. That doesn’t work.” And for example, what I did with Nora — knowing that that part could come from a different country, because the scenes were difficult, and I was not sure I would find the right people in Kinshasa — I wrote the part of someone who comes from outside. She speaks good Lingala in the film. She has a little accent, but that little accent fits with her character. So it would be like, I don’t know, someone from Mexico coming here and speaking in English. But it works, because that’s the character. If it was someone like Riva, with an accent or not being really from Kinshasa, that wouldn’t work. And for Hoji, I did it differently. Apart from Swahili, there is really no African language that everybody can speak. We often speak English or French. And I took it as an Angolan speaking French. So he has an accent in French, but it’s natural as an Angolan coming to Kinshasa.

If you want to play a real guy from Kinshasa, you need to bring some kind of perfume, otherwise the Congolese will say, “Oh Djo, you’re cheating here. That doesn’t work.” And for example, what I did with Nora — knowing that that part could come from a different country, because the scenes were difficult, and I was not sure I would find the right people in Kinshasa — I wrote the part of someone who comes from outside. She speaks good Lingala in the film. She has a little accent, but that little accent fits with her character. So it would be like, I don’t know, someone from Mexico coming here and speaking in English. But it works, because that’s the character. If it was someone like Riva, with an accent or not being really from Kinshasa, that wouldn’t work. And for Hoji, I did it differently. Apart from Swahili, there is really no African language that everybody can speak. We often speak English or French. And I took it as an Angolan speaking French. So he has an accent in French, but it’s natural as an Angolan coming to Kinshasa.

When you get into a film, you must have a feeling that the actor knows what he’s talking about, so eventually you don’t feel that he’s a foreigner, which means that the effort to get inside the character must be a bigger effort than maybe the regular person. I mean, it must have something where you don’t feel that it’s like an outsider. Then it comes to details. As a director, when you depict the characters as having to be accurate about Kinshasa — when you depict an environment, you need to be as real and as close as possible for the people to recognize that environment. Otherwise, they’ll feel a distance. They’ll find it weird and say, “Maybe that’s not the right person.”

What was it like shooting Viva Riva! in Kinshasa, and are you now sold on using digital cameras?

I think shooting went smoothly — as smoothly as it could have been, because people were enthusiastic. They were really willing to help. And the fact that it was a kind of like first feature film in Congo, there was kind of like good energy around. We had the support of the government. We had the support of the population. We had the support of everybody, which made it easy. And especially when you’re an independent filmmaker, you need to change your planning all the time. Because you don’t have enough scenes, or you have to adapt this or that, so we had to improvise a couple of times. That is really where you can feel the input of the population, because they made it easy. If I need a new house, a new street, you can go and ask people. They say, “Yes, you’re welcome.” Al these changes also participated in the success of the film.

I think shooting went smoothly — as smoothly as it could have been, because people were enthusiastic. They were really willing to help. And the fact that it was a kind of like first feature film in Congo, there was kind of like good energy around. We had the support of the government. We had the support of the population. We had the support of everybody, which made it easy. And especially when you’re an independent filmmaker, you need to change your planning all the time. Because you don’t have enough scenes, or you have to adapt this or that, so we had to improvise a couple of times. That is really where you can feel the input of the population, because they made it easy. If I need a new house, a new street, you can go and ask people. They say, “Yes, you’re welcome.” Al these changes also participated in the success of the film.

The problem with digital is that people think it is gonna be easy and magic to make films, which is not true. So it’s not that I want to embrace digital, because every film, every project has it’s own conception. I would like more to focus on using digital as another tool to make the right film. If it’s right, use digital. If it’s not, don’t. It’s most important to have the concept which fits your project, and then you bring the camera that will bring you the atmosphere that you dream of. The Canon D5 was fantastic for this film. You can shoot with really, really little light and create this atmosphere. And at night it’s amazing. This camera does an amazing job.

The problem with digital is that people think it is gonna be easy and magic to make films, which is not true. So it’s not that I want to embrace digital, because every film, every project has it’s own conception. I would like more to focus on using digital as another tool to make the right film. If it’s right, use digital. If it’s not, don’t. It’s most important to have the concept which fits your project, and then you bring the camera that will bring you the atmosphere that you dream of. The Canon D5 was fantastic for this film. You can shoot with really, really little light and create this atmosphere. And at night it’s amazing. This camera does an amazing job.

How did the Japanese film, Stray Dog help inspire the concept for Viva Riva?

Well, Stray Dog is a thriller. It was shot in 1949 in Tokyo from Akira Kurosawa. He was a young director at the time, and the plot is really simple. The detective loses his gun, or someone steals his gun, in the tramway I think. And then there is a question of honor, but also he needs to find his gun, so he starts chasing that person. By chasing the person, he goes into different areas of Tokyo. But actually, what you see in the film is you see Japan after the Second World War. You see it in a really documentary style, really documentary-paced, and I

Well, Stray Dog is a thriller. It was shot in 1949 in Tokyo from Akira Kurosawa. He was a young director at the time, and the plot is really simple. The detective loses his gun, or someone steals his gun, in the tramway I think. And then there is a question of honor, but also he needs to find his gun, so he starts chasing that person. By chasing the person, he goes into different areas of Tokyo. But actually, what you see in the film is you see Japan after the Second World War. You see it in a really documentary style, really documentary-paced, and I  found it brilliant. Because at the time that film was necessary, and you have this right balance between the fiction narrative part, and the documentary part. I watched that film many years ago, and one day I watched it again, and I said, “This should be the concept for Viva Riva.” Have the narrative part, which is a fiction film, but also put it in a documentary environment where you can feel things.

found it brilliant. Because at the time that film was necessary, and you have this right balance between the fiction narrative part, and the documentary part. I watched that film many years ago, and one day I watched it again, and I said, “This should be the concept for Viva Riva.” Have the narrative part, which is a fiction film, but also put it in a documentary environment where you can feel things.

What are the challenges of releasing a film like Viva Riva! to a Kinshasa audience?

Well, basically there are no theaters in Kinshasa, so to release the film is kind of like an extra effort to bring it to the audience. I think they deserve to have a film. In my childhood I used to watch  movies in Kinshasa, so coming back and being there now, and seeing that people do not have the opportunities, it’s a bit sad. So we all are proactive. When I say, “We,” I mean also people in my office. We really try to organize it for the audience. We have a deal with a French cultural center, so they’ve accepted to show the film, kind of like a release. But we’ve also tried to organize something ourselves, in terms of renting a place, buying a projector, have a sound system, some chairs, and find a way to bring the film to popular areas.

movies in Kinshasa, so coming back and being there now, and seeing that people do not have the opportunities, it’s a bit sad. So we all are proactive. When I say, “We,” I mean also people in my office. We really try to organize it for the audience. We have a deal with a French cultural center, so they’ve accepted to show the film, kind of like a release. But we’ve also tried to organize something ourselves, in terms of renting a place, buying a projector, have a sound system, some chairs, and find a way to bring the film to popular areas.

Would a Nollywood-style home video market be an option for Congo?

The problem is that to have home movies, you have to have power first. You know, you need to have some electricity first to watch your film. So what I’m talking about in my film in terms of infrastructure, we have deeper problems than, for example, Nigeria. And the size of the economy is also different. But I think home movies will develop everywhere. And also, I think VOD will be the main thing for Congo in the future, and people will be able to download films to watch them at home — and maybe [affect] the distribution. Because even to have a home theater system, you have to have a system of distribution, which is not easy to organize in a city which is so not-well-organized in that sense. And so, VOD will be an answer I think for the future.

The problem is that to have home movies, you have to have power first. You know, you need to have some electricity first to watch your film. So what I’m talking about in my film in terms of infrastructure, we have deeper problems than, for example, Nigeria. And the size of the economy is also different. But I think home movies will develop everywhere. And also, I think VOD will be the main thing for Congo in the future, and people will be able to download films to watch them at home — and maybe [affect] the distribution. Because even to have a home theater system, you have to have a system of distribution, which is not easy to organize in a city which is so not-well-organized in that sense. And so, VOD will be an answer I think for the future.

The challenge about bringing films to people is that we need to bring cinema — not only that you see the story on a little format. Cinema is all in the journey about going, buying your ticket, sitting there in a dark room, having proper sound, a proper image, which is a big image so you can see all the little details that you put in the films that you maybe won’t be able to see on a small screen.

Describe the international team of financiers/producers on Viva Riva, and how you pitched them.

The dynamics and times are complex. Boris Van Gils, who is the main producer of the film with Michael Goldberg, I met them 10, 11 years ago. With Boris, we had a drink at a party for a friend of ours who is a Chilean cameraman. We start talking, and that was the beginning of it. And then I moved back to Congo, we had this project, and we were looking for money in different places, including South Africa with my partner Steven Markovitz. Actually, I wrote this film for cinephiles. I myself am a cinephile, so I believe in the family of cinema as cinephiles all around the world, and the idea was to have a story where people could just relate to it and enjoy it. What did happen is

The dynamics and times are complex. Boris Van Gils, who is the main producer of the film with Michael Goldberg, I met them 10, 11 years ago. With Boris, we had a drink at a party for a friend of ours who is a Chilean cameraman. We start talking, and that was the beginning of it. And then I moved back to Congo, we had this project, and we were looking for money in different places, including South Africa with my partner Steven Markovitz. Actually, I wrote this film for cinephiles. I myself am a cinephile, so I believe in the family of cinema as cinephiles all around the world, and the idea was to have a story where people could just relate to it and enjoy it. What did happen is  that finally we had French television, Canal Plus, who got involved. We had the Belgian film fund also get involved. You know, it was surprising to see all these people coming along, and probably it’s also the sign of times that things are changing maybe. At least there is an interest, and the fact that the film is doing well encourages everybody to do more. I hope they will.

that finally we had French television, Canal Plus, who got involved. We had the Belgian film fund also get involved. You know, it was surprising to see all these people coming along, and probably it’s also the sign of times that things are changing maybe. At least there is an interest, and the fact that the film is doing well encourages everybody to do more. I hope they will.

The only state funds you have in Africa, you have in South Africa, you have in Morocco, a bit in Nigeria, but not much more than that — maybe Kenya. So finding money in Africa is very, very tough, and businessmen for the moment are not willing to invest into cinema, because they don’t understand or they don’t believe in it. So it’s a long process, though it’s also a long-term vision of working in Africa.

Steven Markovitz has a production company in South Africa, and I’m in Congo, and we are together in the Southern region of Africa. And so, we have decided to have a partnership where we work in both countries. Also, I come from a French-speaking country in Congo, and he comes from an English-speaking country. But also, we want to make these films that have like a cross-barrier relation, which doesn’t happen often in Africa. And we have produced together documentaries like Congo in Four Acts, which was quite successful in festival. And we also did this film together, Viva Riva!, where he acted as a co-producer. And we do other things, so the idea is we try to be modern Africans. We try to, for example, bring theaters to my country. But maybe for South Africa the changes are different. Maybe bring more independent films. Maybe develop stories which are more linked to a certain artistic vision about Africa. So we try to get along and develop things.